An introduction to trusts

What are trusts?

The origins of trusts

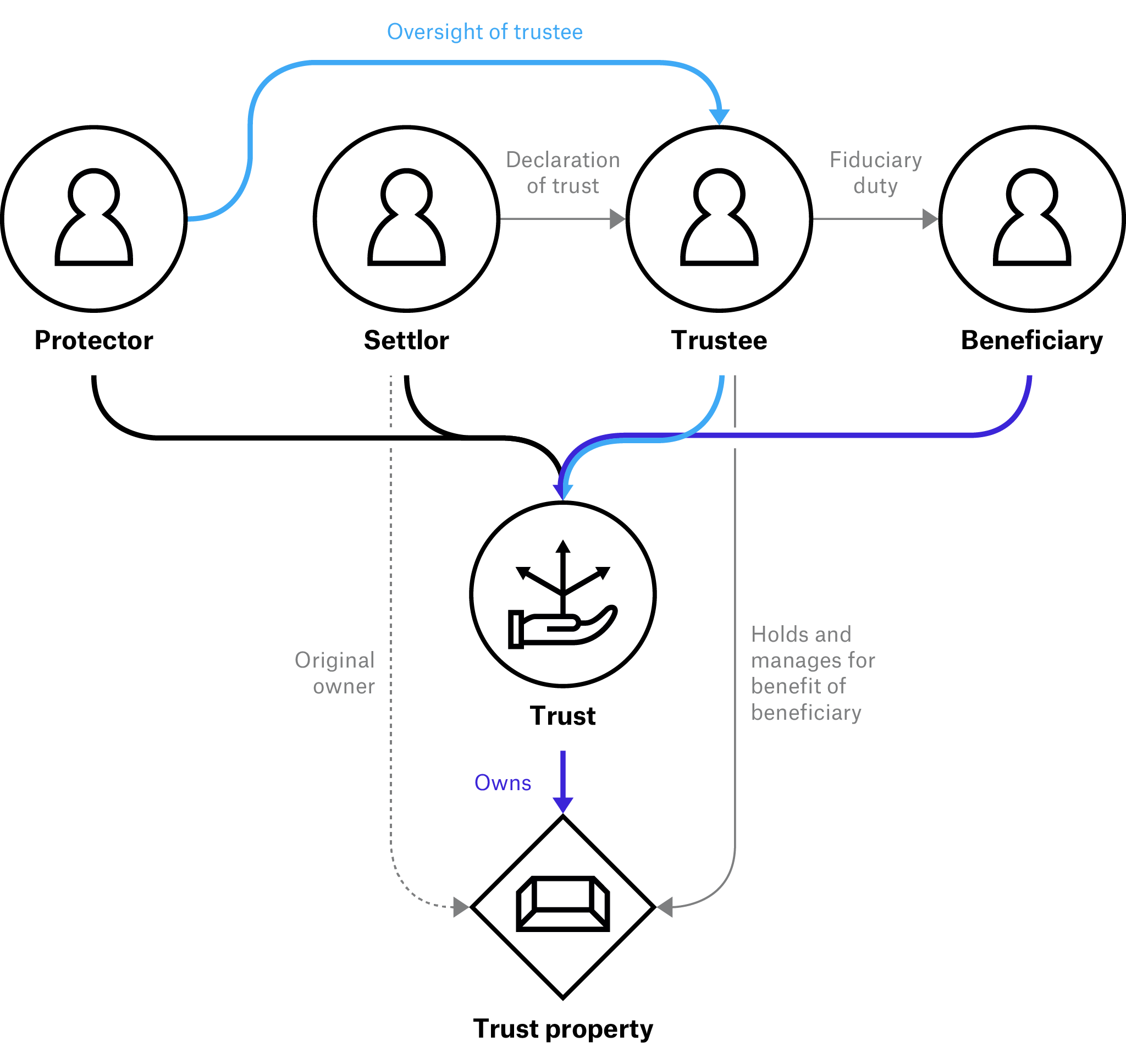

A trust is usually defined as a legal arrangement or relationship in which a person or entity (“trustee”) owns and manages property or assets, entrusted by a person or legal entity (“settlor”) not for their own use or benefit but with a fiduciary responsibility to act for the benefit of persons or entities specified (“beneficiaries”), as described under the terms of the trust (e.g. a trust deed).[2] In a trust, a “trustee holds legal title to the trust property, and the beneficiaries have equitable or beneficial ownership [BO].”[3] Some trusts also feature “protector(s)” – a party which has some level of control over the trustee(s).

Trusts are widely regarded as one of the hallmarks of the legal systems of the common law family. Their origin can be traced back to the Middle Ages (in the 11th or 12th century) in England, when trusts (then known as “Uses”[4]) were used by knights to transfer their land (without any consideration) to a trusted third party when leaving to fight in the Crusades so that the feudal services could continue to be performed and received.[5] Originally, trusts were not enforceable in any court but existed purely as honorary obligations between the parties.[6] Later, however, during the reign of Richard II, the Court of Chancery started enforcing trusts to protect the property rights of knights. It was recognised that in a trust a third party was obliged to hold and manage the property entrusted to it only for the benefit of the knight and his family until his return, or to pass it onto a designated son of the knight upon his death.[7] In common law, under the concept of trusts (or Uses), as it was developed by the courts of equity, it was thus made possible to split the ownership of the property between the legal owner of the interest of the property – the trustee – and the owner of the interest in equity, i.e. the actual beneficiary of the property held by another person.

Later, with the certainty of the enforcement of the trust by the Courts of Chancery, the use of trusts became popular, as in addition to providing secrecy regarding real ownership, trusts also provided a series of protections and privileges not afforded by the common law.[8] Landowners started using trusts to find a way around the inheritance rules and to convey property rights to their family members or friends upon death, especially when it was not legally possible to transfer freehold estates by making wills.[9] They have been used to avoid paying any feudal inheritance taxes,[10] for asset protection,[11] and to enable religious houses to obtain profits on their land, notwithstanding the restrictions placed by the statutes of mortmain.[12]

The creation of trusts and their use for legitimate purposes were enforced by the courts. At the same time, abuses of trusts also emerged, and a body of law developed in England over the centuries under both common law and statutory law to regulate trust arrangements. This process is summarised by Lewin, who wrote about trusts extensively in the early 19th century, and said that “the origin of trusts, or rather the adaptation of them to the English law, may be traced in part at least to the ingenuity of fraud”.[13]

Trusts in civil law legal systems

Trusts did not exist in Roman law, and they do not exist in the civil legal systems that are derived from Roman law.[14] However, this does not mean that trust-like arrangements do not exist in civil legal systems. There are arrangements such as fiducia,[15] certain types of Treuhand,[16] fideicommissum,[17] private foundations,[18] and waqf,[19] which are operational in different jurisdictions. Although these trust-like legal arrangements have different origins, they share the same nature, features, and functions as trusts. In all these legal arrangements, similar to trusts, the property is entrusted to one person who is obliged to hold the title and manage the property, not for their own benefit but for the benefit of a different party.

However, there are some differences in these legal arrangements in civil law systems and trusts, which include the following:

- A trust is not a legal entity or a contract whereas similar instruments discussed above are either of contractual nature, such as Treuhand and fiducie, or are legal entities, such as private foundations.[20]

- Private foundations are similar to trusts in their function, ownership, and control structure, and they are subject to common regulations, for instance, via the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Common Reporting Standards (CRS) for automatic exchange of information. However, unlike trusts, private foundations are required to be properly registered and incorporated before starting to operate in many civil law countries. In Austria and France, for instance, fiducie and private foundations have to be registered.

Additionally, whilst certain jurisdictions may not allow trusts to be created domestically, these need not necessarily prohibit foreign law trusts from operating within the jurisdiction.

Overall, jurisdictions worldwide take different approaches to the treatment of trusts, and may be broadly categorised into:

- Trust law jurisdictions: Jurisdictions which recognise or allow the creation of trusts under their domestic law;[21] and

- Non-trust law jurisdictions: Jurisdictions which do not allow the creation of trusts under their domestic law. Such jurisdictions, however, need not necessarily prohibit foreign law trusts from operating within the jurisdiction or from being administered by trustees residing in their territories.[22]

Main types of trusts and trust-related parties

Broadly, trusts can be divided into three main types:[23]

- Express trusts: Express trusts, as they are known in English law, are trusts that are deliberately established by a settlor, as opposed to having been created either through a statute or a court order. They are usually created by instruments expressly indicating the persons, property, and purposes of the trust so that their duration and nature are certain.

- Implied trusts: Implied trusts are those that are not expressly declared, but are created by operation or construction of law either for the purpose of carrying out the presumed intent of parties or to rectify fraud and prevent unjust enrichment.[24] Implied trusts are of two types:[25]

- Constructive trusts: Constructive trusts are often created by the law of equitable obligations (law of equity) as a convenient means to remedy unjust enrichment, especially in the case of fraud or wrongdoing. For instance, if Person A procures legal title to a property from Person B by committing fraud, misrepresentation, or concealment, Person A becomes a trustee who holds the property in trust for Person B by operation of the law of equity.

- Resulting trusts: Resulting trusts are declared by the law of equity to exist because of the presumed intention of the parties that they shall exist, as implied from the act or transaction of parties. For instance, if Party A gives money to Party B for purchase of the property which has never been returned to Party A, the law of equity will imply that Party B is not an absolute owner of the property and is holding the property in trust for Party A.

- Statutory trusts: Statutory trusts arise when mandated by a statute requiring that under certain circumstances the property shall be held in trust. Such instances include, for example, in the case of legal estates that are co-owned, part of an intestate succession, or in bankruptcy.

Trusts are also categorised as: private trusts, which vest the beneficial interest on individuals or families; and public trusts, which are for the benefit of the public at large or some particular portion of it. Charitable trusts, developed for charitable purposes or objects, belong to the class of public trusts and, indeed, public trusts and charitable trusts may be regarded in general as synonymous expressions.[26]

The expression “trust” as it is used in this paper refers only to “express trusts”, which are the main focus of international standards – whether they be the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendations, the European Union’s (EU) Anti-Money Laundering Directives (AMLD)[27] or the OECD CRS.[28] This is due to their nature, being purposely or deliberately created by private parties – making them more vulnerable to abuse for criminal purposes, as compared to other types of trusts, i.e. implied or statutory trusts.

Express trusts

Express trusts can be of various types, based on the purpose for which they are created (see Box 1). The name given to a trust might not be indicative of its true nature, purpose, and control structure. To understand the arrangement between different parties to a trust – such as settlor(s), trustee(s), protector(s) (if any), or beneficiaries or class of beneficiaries – and the extent to which each party exercises its control over a trust, it is important to determine not only the type of trust but also the terms of the trust deed, letter of wishes,[29] or power of attorney establishing the trust.

Box 1: Types of express trusts

- Charitable trusts: Where the trust assets/property is managed by the trustee solely with a charitable purpose, for example, to relieve poverty, advance education or religion, or any other community benefit.

- Bare trusts: Where the property or assets are held in the name of a trustee, but the trustee has no discretion over what income is paid to the beneficiary and has no active duties to perform. The beneficiary has the absolute right to all of the capital and income of the trust once they turn a certain age (e.g. 18). At that age, assets set aside by the settlor will always go directly to the intended beneficiary.

- Blind trusts: A trust in which the beneficiaries do not have knowledge of the trust’s specific assets, and in which a fiduciary third party has complete management discretion.

- Life interest trusts: This form of trust is designed to protect the family home. Each individual’s share of the jointly owned property is preserved for the benefit of their children, whilst surviving partners may occupy the property for the remainder of their lifetime.

- Discretionary trusts: These allow the settlor to place the assets under trust at the discretion of the trustee(s), who will decide whom is to benefit and how. A settlor may wish to do so to protect himself against forced heirship rules. The settlor will usually draft a letter outlining their wishes to the trustee. This is the most flexible and common form of trust.

- Self-settled trusts: Trusts in which a settlor can also be a beneficiary of the trust. Technically, in such trusts there is no meaningful separation between the settlor and assets.

Contrary to discretionary trusts, there are, for instance:

- Settlor-directed trusts: trusts in which the settlor actually directs the trustees in all investment-related matters and asset distributions; and

- Settlor-interested trusts:[30] trusts in which the settlor or their spouse or civil partner benefits from the trust.

Parties to a trust

In a typical trust, there are usually three parties: settlor, trustee, and beneficiary (or class of beneficiaries), as demonstrated in Box 2 below. There could also be a protector, depending upon the creation and purpose of the trust, and there will always be a trust property.

Box 2: Parties to a trust

Settlor: A settlor is a person who, either actually or by operation of law, creates a trust.

Trustee: A trustee is a person who administers the trust, and in whom the legal title of the trust property is vested, either by declaration of the settlor or by operation of law.

Beneficiary: A beneficiary is a person(s) in whom the equitable and beneficial title to the trust property is vested, and for whom the trustee has to hold and manage the trust property.

Protector: A protector protects the interests or wishes of the settlor, providing influence and guidance to the trustee. Not all trusts have a protector.

Trust property: The trust property is the property, either real or personal, which is the subject of the trust.

Main uses of express trusts

Legitimate uses

Express trusts can be created for a variety of legitimate purposes that can, according to Austin Scott, a Harvard professor who wrote a ten-volume treatise on trusts, “go beyond even the imagination of lawyers”.[31] The most common legitimate uses for which express trusts are created include:

- Estate and inheritance planning, i.e. to organise an inheritance by transferring the estate administration to a third party.

- Asset protection, i.e. to control and protect family assets for children, classes of family members, or vulnerable adults.

- Administration and provision related to vulnerable persons, such as minors, addicts, and people living with disabilities; for instance, when someone is too young, trusts are used to handle their financial affairs (e.g. until the individual turns 18, the trustee will manage the assets).

- Management and distribution of pension or retirement funds; for example, to invest money with the view to finance an important expense in the future (e.g. retirement or education fees).

The use of express trusts for commercial purposes has also become a common feature. Trusts have evolved from being a private arrangement[32] between parties to a valuable device in commercial and financial transactions. A trust operates in this arena as an entrepreneur or a business entity (despite not being a separate legal entity). It raises equity funds from investors who acquire beneficiary status by purchasing an equitable interest. It can borrow and incur substantial debts, and it can apply the aggregated equity and debt funds in risk-taking enterprises.[33] Commercially, trusts are broadly used for three purposes:

- Investment: for instance, when they are used to manage an investment portfolio (e.g. real estate investment trusts (REITS) in the UK). Examples of trusts as an investment vehicle include unit trusts, pension fund trusts, and employee benefit trusts.

- Special purpose trusts: to hold money or other property in a separate pool for a specific purpose; for instance, to provide security for a loan or as insurance to address possible future claims against the beneficiaries of the trust. Examples include debenture and bond trusts, as well as sinking fund trusts.

- To undertake business or trade as companies: Examples of business purpose trusts include trading trusts, asset finance structures, voting trusts, structured finance, and securitisation.

Box 3: Data trusts

There are also more contemporary applications of trusts. Recently, trusts have been established to help govern data for the public good in so-called “data trusts”, the purpose of which is to provide independent, fiduciary stewardship of data.

Data trusts have been defined by the Open Data Institute as “a legal structure that provides independent stewardship of some data for the benefit of a group of organisations or people.”[34]

As explained by the Open Data Institute, “in a data trust, the [settlors] may include individuals and organisations that hold data. The [settlors] grant some of the rights they have to control the data to a set of trustees, who then make decisions about the data – such as who has access to it and for what purposes. The beneficiaries of the data trust include those who are provided with access to the data (such as researchers and developers) and the people who benefit from what they create from the data.”[35]

The Open Data Institute goes on to say: “With data trusts, the trustee[s] who might be an independent person, group or entity stewarding the data takes on a fiduciary duty … [which] involves stewarding data with impartiality, prudence, transparency and undivided loyalty.”[36]

Illegitimate uses

The inherent characteristics of a trust – particularly the separation of legal and beneficial ownership (BO) – make trusts particularly useful for those who want to distance and disguise their connection with any property or assets, generated either legally or illegally. Through a trust, a settlor can give up legal ownership of the property whilst still maintaining distant control over the assets, which entirely depends upon the terms of the confidential trust deed or the arrangement between the parties (e.g. use of a protector, letter of wishes, etc.). Such a distant control can allow a criminal to de-link the assets from their criminal conduct and also provides them with asset protection.

Trusts have been widely used to illegitimately safeguard assets from legitimate creditors (for example, in cases of bankruptcy), financial setbacks, family disagreements, divorce, and lawsuits, because once the settlor has assigned the assets to a trust, in most cases the assets are no longer deemed to be personal possessions of the settlor. In fact, as described by Andres Knobel, lead researcher of BO at the Tax Justice Network, the assets of a trust are in “ownership limbo” till they are distributed to the beneficiary or class of beneficiaries, which means they do not constitute the personal wealth of any of the parties to the trust to enable a successful claim for payment.[37]

This is the feature of trusts that has been used in some jurisdictions to attract the establishment of trusts within their jurisdiction. For instance, jurisdictions such as the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, the Cook Islands, Nevis, and many states in the USA offer different types of “asset protection trusts”. Whilst these can be set up for legitimate purposes, their secrecy can be exploited for illegitimate purposes and “could be abused precisely to keep creditors (including former spouses and legitimate heirs) off one’s wealth.”[38] Some jurisdictions also offer non-recognition of foreign laws and foreign judgements as a part of their trust regimes which will make them more attractive to trust businesses.[39]

The past few years have also witnessed various reports and scandals where the abuse of trusts for illegal purposes has been strongly highlighted. Some of these include the World Bank’s Puppet Masters report,[40] the FATF’s Concealment of Beneficial Ownership report,[41] and the Panama Papers, which described how trusts have been involved in major tax evasion, money laundering, and corruption scandals. Trusts are often used as the last layer of secrecy in complex corporate ownership structures, to obfuscate BO and disguise a criminal’s connection to illicit funds.

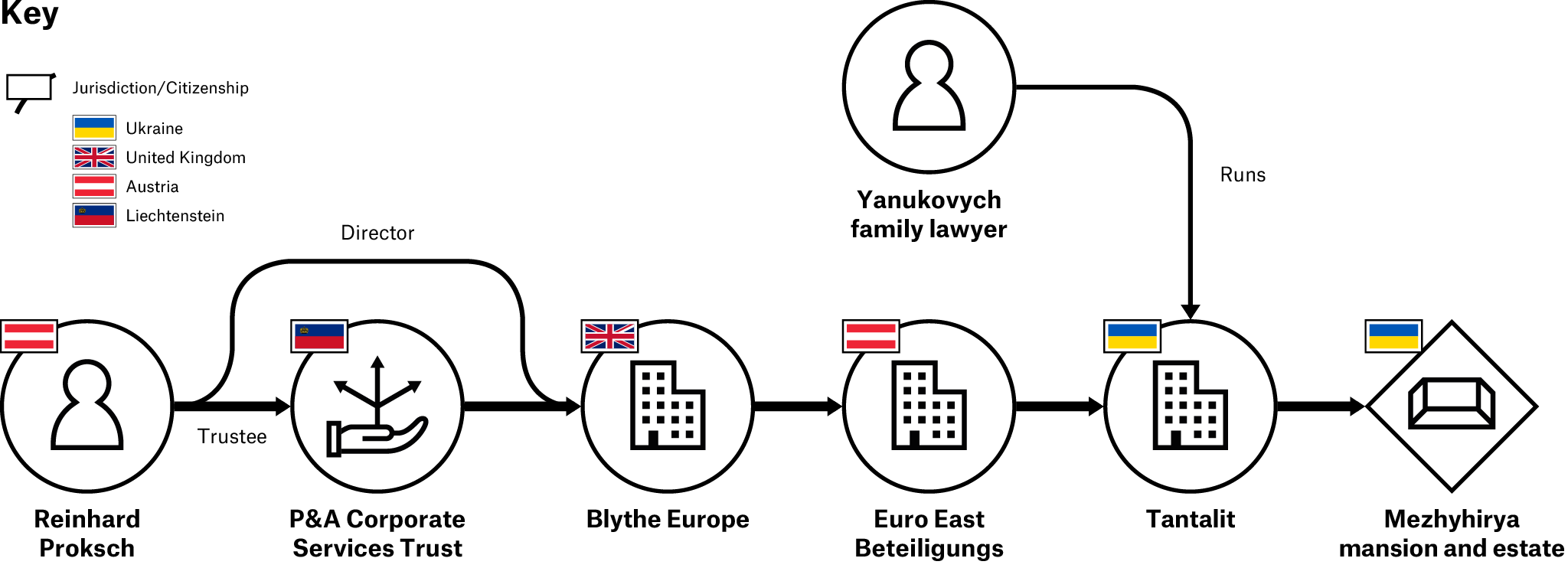

Box 4: Use of trusts for corruption in Ukraine[42]

In Ukraine, a multi-million dollar presidential palace, Mezhyhirya, and its surrounding estate were privatised and sold during the second term of the Former President, Victor Yanukovych, for an undisclosed amount. Through a complex structure of corporate vehicles, the palace was found to be ultimately owned by a Liechtenstein trust – P&A Corporate Services Trust, with Reinhard Proksch, an Austrian national, as a trustee.

Due to the secretive nature of trusts, no further details about the settlor or beneficiaries of the trust were disclosed, making it difficult to determine who is the ultimate beneficial owner of this estate.

Box 5: Examples of the use of trusts for tax evasion and avoidance[43]

- USA: Billionaire Sam Wyly was convicted in “one of the largest tax evasion cases in history” and received a USD 1.3 billion tax bill, after shielding wealth using a web of offshore trusts.

- France: Prosecutors accused international art dealer Guy Wildenstein of hiding his art and assets from the French authorities under the ownership of a web of trusts, for which the French tax authorities sought back taxes of more than EUR 550 million.

- UK: The Duke of Westminster inherited an estate worth GBP 9 billion held in trust and avoided paying approximately GBP 3 billion inheritance tax, applicable if he had received it outright.

There are three main types of express trusts that have been highlighted as being particularly vulnerable to criminal abuse: discretionary trusts, charitable trusts, and self-settled trusts.[44] This is likely to be due to the nature of these trusts, which makes it difficult to identify their ultimate BO.

- Discretionary trusts: In a discretionary trust, for instance, a trustee has been given the discretion to decide how, when, and to whom they want to distribute trust assets (although this might have been secretly determined by a letter of wishes[45]). Until the trustee actually decides and distributes the trust assets, beneficiaries will only hold contingent interest in the trust, which will protect their assets from creditors, spouses, or in any lawsuits. It also raises an issue when disclosing BO of trusts as to who should be disclosed as beneficiaries to the relevant authorities, or to any centralised BO register (both for legal persons and legal arrangements, if established), if no one has yet been determined to receive, or has received, the distribution of trust assets.

- Charitable trusts and foundations: Charitable trusts and foundations have been identified in a number of case studies and reports as being abused for criminal purposes.[46] This is primarily due to the wider public trust that they enjoy, as well as a number of privileges that have been granted to them in various jurisdictions, including tax exemptions and exemptions from the rule of perpetuities.[47] For instance, a trust which has been created to protect vulnerable children might in reality be used to hide the proceeds of corruption, to launder illicit money, or to evade taxes.

- Self-settled trusts: As discussed earlier, self-settled trusts are those in which a settlor can also be a beneficiary of the trust. As there is no meaningful separation between the settlor and assets,[48] these trusts are often argued to be vulnerable for misuse for criminal purposes (see: Box 6).

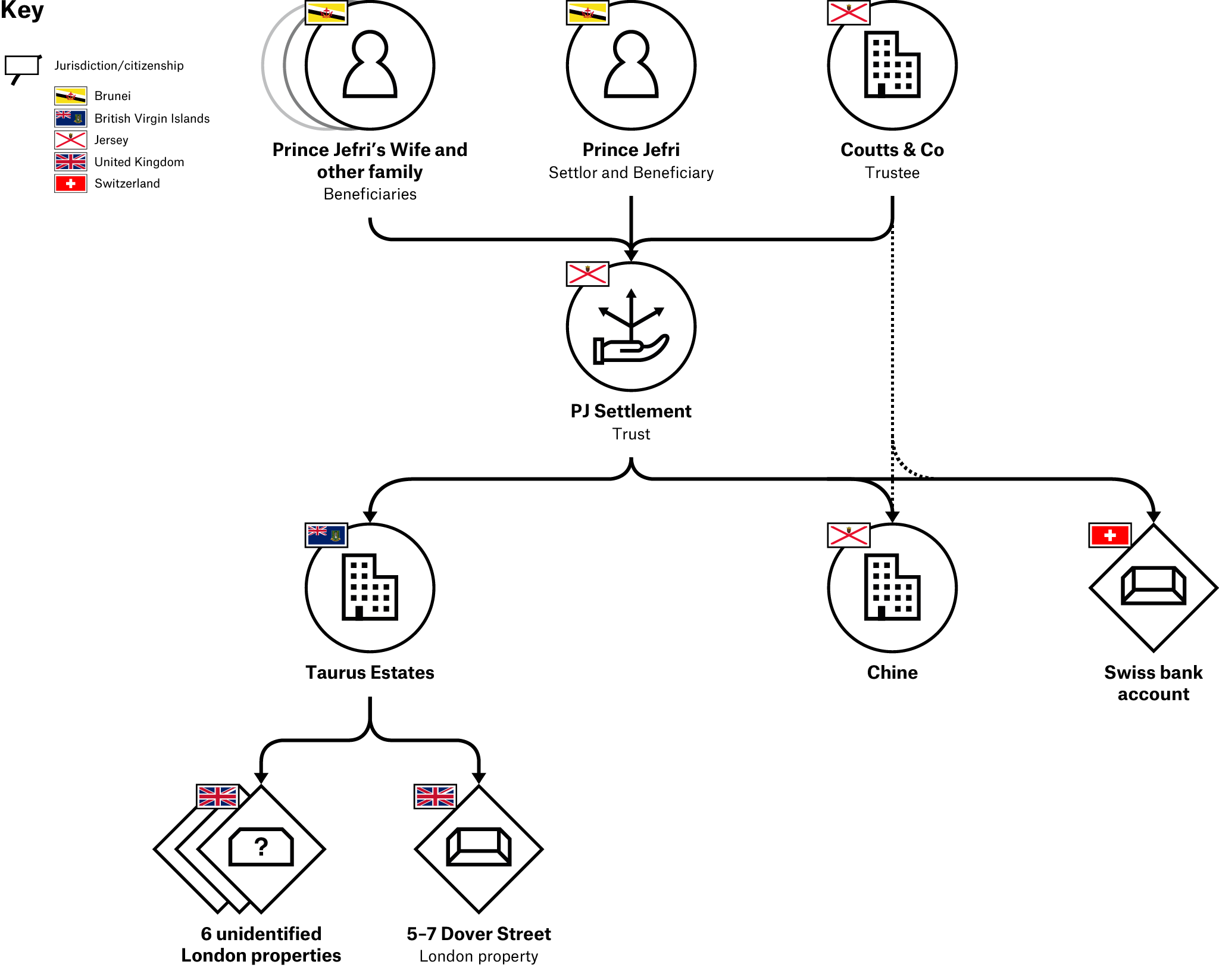

Box 6: An example of misuse of self-settled trusts[49]

In this example from Brunei, a Jersey-based trust was used to hide the ownership of a property in London. This was a “self-settled trust” set up by Prince Jefri and its beneficiaries were Prince Jefri and his family members.[50]

In an out-of-court settlement for corruption and fraud charges for more than USD 14 billion, Prince Jefri agreed to return over 70 of his worldwide properties to the Brunei Investigation Agency.

As a result of the widespread misuse of trusts, there has been a push to attempt their regulation, for instance, by the 5th EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD5). This is discussed in more detail in the OO policy briefing Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

Footnotes

[2] Various definitions of a “trust” can be found in the recognised textbooks and journal articles which deal either exclusively or incidentally with the subject of trusts. See, for instance: J.H. Thomas, A Systematic Arrangement of Lord Coke’s First Institute of the Laws of England (Vol. II, S. Brooke, Paternoster-Row, 1818), 570; Arthur Underhill, The Law Relating to Private Trusts and Trustees (4th edn, F. H. Thomas Law Book Co. 1986), 1; J. H. Baker, Snell’s Equity (32nd edn, Sweet & Maxwell, 2010), 623; Walter G. Hart, “What is a Trust?” (1899) 15 Law Quart. Rev. 294, 301; George Bispham et al., The Doctrine of Equity: A Commentary on the Law as Administered by the Court of Chancery (5th edn, T. & J. W. Johnson, 1868), 77.

[3] R. H. Sitkoff, “Trusts and Estates: Implementing Freedom of Disposition” (2014 58 st. Louis ULJ), 658.

[4] A trust was known in ancient times as a “Use”, which existed prior to the enactment of the Statute of Uses (St. 27 Henry VIII.c.10) in 1535. A “Use” is generally described as “a device for the ownership of property, whereby one person became the owner of the legal title, which he held for the benefit of a third party” (Edward J. O’Toole, Law of Trusts (Brooklyn, N.Y., s.n.), 1). Modern trusts are, for the most part, an outgrowth of the practice of enfeoffing to “Uses” which prevailed in England in the Middle Ages.

[5] Scott Atkins, Equity and Trusts (1st edn, New York, Routledge, 2013), 24-53.

[6] In the Middle Ages, a “Use” was most frequently created by a feoffment to A and his heirs for the use of B and his heirs. Originally, the only pledge for the due execution of the trust was the faith and integrity of the trustee. The courts of common law did not recognise the claims of the knights or their beneficiaries because no writ to file a claim existed for that purpose. Nonetheless, it was in the reign of Richard II that the writ of subpoena was invented to summon the trustee into the Court of Chancery to answer under oath the allegations of trust’s beneficiaries. The Court of Chancery began to enforce “Uses” and trusts in the early part of the fifteenth century. See: George G. Bogert, Handbook of the Law of Trusts (West Publishing Co., 1921), 9; Walter Banks (ed.), Lewin’s Practical Treatise on the Law of Trusts (Sweet & Maxwell, 1928), 1.

[7] Banks, Lewin’s Practical Treatise on the Law of Trusts, 1.

[8] Edward J. O’Toole, Law of Trusts (Brooklyn, N.Y., s.n.), 6.

[9] Ibid. See also: Banks, Lewin’s Practical Treatise on the Law of Trusts, 1.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid (a “Use” was not subjected to the incidents of feudal tenure, such as forfeiture for treason or felony, wardships or marriage). See also: Bogert, Handbook of the Law of Trusts, 6 (a “Use” was used to protect the land from “the rights of the lord under feudal tenure, the rights of creditors, and the rights of dower and courtesy”).

[12] Ibid.

[13] Banks, Lewin’s Practical Treatise on the Law of Trusts, 1.

[14] David Johnston, The Roman Law of Trusts (Caledonian Press, 1988).

[15] The fiducia is used in certain civil law countries, such as France, as a means by which a person (constituant) transfers property to someone (Fiduciarie) who has a legal title to the property and is responsible for managing the property for someone else, but derives no personal advantage from the transfer. It was originally used to transfer the property to a creditor or manager by a formal act of sale, yet with an agreement that the creditor would reconvey the property upon payment of a debt – they had legal title over the property and were required to manage it, but could not have any personal gain from the property.

[16] Treuhand is a contractual relationship wherein a person (the Treuhtinder) is entrusted with certain property (the Treugut), which they have to administer or dispose of, not in their own interest but in the interest of another person (the Treugeber) or for a specific purpose. No law explicitly governs Treuhand, but they are governed by academic writings and case law. Treuhand exists, for instance, in Austria, Germany, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland.

[17] In legal English, “fideicommissum” is the equivalent of “trust”. Fideicommissum are among the most versatile legal institutions of Roman law that developed outside the Roman formulary system in a new official procedure, similar to trusts, which developed in equity, outside the common law. The Latin term fideicommissum implied entrusting an object (commisum) to the good faith (fides) of the recipient, for the benefit of another person. Fideicommissum exists, for instance, in Mexico. To read more on fideicommissum, see: Johnston, The Roman Law of Trusts.

[18] Private foundations exist, for instance, in Austria, Belgium, Hungary, and Netherlands Antilles.

[19] Waqf is an institution prevalent in Islamic countries. In Islamic Sharia’a law, the waqf is usually “established by a living man or woman, known as the waqif (founder/settlor) who hold a certain property to place that property under the possession of a fiduciary (wali or mutawalli) to assure that the confined waqf reaches the intended beneficiaries (mustahiqeen), and is prohibited from sale, gift and inheritance.” See: H. Suleiman, “The Islamic Trust Waqf: A Stagnant or Reviving Legal Institution?”, 2016, Electronic Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Law (EJIMEL), 4. For a comparative analysis of trusts and waqf, see: Irina Gvelesiani, “The Trust and the Waqf (comparative analysis)”, 26 (8-9) Trust & Trustees, 2020, 737; Katrin Sepp, “Legal arrangements similar to trusts in Estonia under the EU’s Anti-Money-Laundering Directive”, 26 Juridica International, 2017, 56.

[20] Ibid.

[21] In the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index 2020, 133 jurisdictions have been assessed, identifying 90 jurisdictions as trust law jurisdictions where domestic law trusts are available and 42 jurisdictions as non-trust law jurisdictions which do not allow trusts to be created pursuant to their own domestic laws. For more details, see: “Financial Secrecy Index”, Tax Justice Network, 2020, https://fsi.taxjustice.net/en/explore/database.

[22] Ibid.

[23] For the purposes of this paper, a broader classification of trusts into express, implied, and statutory trusts has been used. However, there are other multiple classifications of trusts as well, such as simple or passive trusts and special or active trusts; lawful and unlawful trusts; public and private trusts; executed or executory trusts; revocable or irrevocable trusts; inter vivos or testamentary trusts; fixed or discretionary trusts. For more details, see: James H. Flint, Law of Trusts and Trustees as Determined by the Decisions of the Principal English and American Courts (Bancroft-Whitney Company, 21st edn, 1890), 1-6.

[24] Henry Godefroi, The Law relating to Trust and trustees (5th edn, Stevens and Sons, 1927), 3. See also: Flint, Law of Trusts and Trustees as Determined by the Decisions of the Principal English and American Courts, 6 (“A frequent case of implied trust arises where words precatory, recommendatory, or expressing a belief are used by a testator, such as commonly known as precatory trusts”).

[25] See: Bogert, Handbook of the Law of Trusts, 92; Godefroi, The Law relating to Trust and trustees, 3; Atkins, Equity and Trusts, 24-53; John N. Pomeroy, A Treatise on Equity Jurisprudence (3rd edn, Bancroft-Whitney, 1905). In some writing, however, implied, constructive, and resulting trusts are classified separately. See, for instance: Flint, Law of Trusts and Trustees as Determined by the Decisions of the Principal English and American Courts, 5-6; Arthur Underhill, The Law Relating to Private Trusts and Trustees, 11-12; Jarius W. Perry, A Treatise on the Law of Trusts and Trustees (2nd edn., Brown Little, 1874).

[26] Banks, Lewin’s Practical Treatise on the Law of Trusts, 16.

[27] See: “Directive (EU) 2018/843”, European Union, 30 May 2018, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018L0843&from=EN; “Directive (EU) 2015/849”, European Union, 20 May 2015, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32015L0849&from=EN.

[28] Standard for Accounting Exchange of Information in Tax Matters, OECD, (2nd edn, Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018).

[29] A letter of wishes is a document written by the settlor of a trust to the trustee(s) to guide them as to how the settlor would like the trust to be administered by the trustee(s) even when exercising their discretionary powers. A letter of wishes is not binding on the trustee(s) and often accompanies a discretionary trust, where the trustee(s) may be in need of guidance.

[30] “Self-interested trusts” are also known as “self-settled trusts”. Establishing a self-settled trust is not prohibited, at least in the UK; however, these types of trusts have been termed as “sham” trusts (see: Andres Knobel, “‘Trusts: Weapons of Mass Injustice?’ A response to the critics”, Tax Justice Network, 25 September 2017, 32, https://taxjustice.net/2017/09/25/response-criticism-paper-trusts-weapons-mass-injustice/; Murray Worthy, “Don’t take it on trust”, Global Witness, 22 February 2017, https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/corruption-and-money-laundering/anonymous-company-owners/dont-take-it-trust/). Knobel and Worthy reason that a) such trusts are not created to benefit others – the very reason for the existence of trusts; and b) despite the settlor transferring the legal title of the assets to the trustee, the settlor retains control of, or is one (or maybe the only) beneficiary of such trust. It has been argued that such trusts are mainly created to shield assets from outsiders for personal benefit.

[31] Austin W. Scott and William F. Fratcher, Introduction to the Law of Trusts 2 (4th edn, 1991). On the uses of trusts, see also: Robert Dumont, “International tax and estate planning for high-net-worth families” Tax Notes International, 2010, 57(9), 785; Robert C. Lawrence III, International Tax and Estate Planning: A Practical Guide for multinational Investors (3rd edn, Practising Law Institute, 2017); Edward C. Halbach, “The Uses and Purposes of Trusts in the United States”; David Hayton (ed.) Modern International Developments in Trust Law (Boston: Kluwer Law International, 1999) 123, 133-142.

[32] The term “private arrangement” is used here to describe an arrangement which is confidential between the parties to a trust (without any information or document being disclosed to the public) and used mainly for private purposes, such as family matters, inheritance, asset protection, etc.

[33] Ruiqiao Zhang, “The new role trusts play in modern financial markets: the evolution of trusts from guardian to entrepreneur and the reasons for the evolution”, 23(4) Trust & Trustees, 2017, 453, 454. Some of the features of trusts that make them attractive for commercial purposes include: “a) their inherent flexibility, usually providing expansive powers to the trustee(s) to conduct business, and little regulatory control (except for certain trusts, such as pension fund trusts, etc.); b) the independence of the trust property from the personal property of either settlor or trustee, a proprietary feature of the trust, which not only protects the trust assets from the claims of trustee’s or settlor’s personal creditors or spouse in the event of bankruptcy or divorce but also allows assets held for commercial transactions from that person’s balance sheet, for insolvency risk management or taxation purposes; c) the segregation of legal ownership and beneficial ownership of trust property that offers inbuilt protections for beneficiaries and contracting third parties through the imposition of personal liabilities on trustees makes them attractive to investors; d) ability to circumvent legal obstacles, such as facilitating certain type of investments and taxation treatment; e) advantages of a trust over a company, for instance, no registration for their existence, less formalities, protection from company’s business risks, including its risk of bankruptcy.” (461).

[34] Jack Hardinges, “Defining a ‘data trust’” Open Data Institute, 19 October 2018, https://theodi.org/article/defining-a-data-trust/.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Jack Hardinges, “What is a data trust?” Open Data Institute, 10 July 2018, https://theodi.org/article/what-is-a-data-trust/.

[37] Knobel, “‘Trusts: Weapons of Mass Injustice?’ A response to the critics”.

[38] Andres Knobel, “Beneficial Ownership and Disclosure of Trusts: Challenging the Privacy Argument”, Tax Justice Network, 17 December 2016, https://www.taxjustice.net/2016/12/07/beneficial-ownership-disclosure-trusts-challenging-privacy-arguments/.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Emile van der Does de Willebois et al., The Puppet Masters: How the Corrupt Use Legal Structures to Hide Stolen Assets and What to Do About It, StAR, UNODC, and World Bank, 2011, https://star.worldbank.org/sites/star/files/puppetmastersv1.pdf.

[41] Concealment of Beneficial Ownership, FATF, (Paris: FATF, July 2018).

[42] Worthy, “Don’t take it on trust”.

[43] Knobel, “‘Trusts: Weapons of Mass Injustice?’ A response to the critics”, 9-10. A distinction is usually made between tax avoidance and tax evasion, the former being used to refer to a legal reduction in taxes, whilst the latter being used to refer to tax reductions that are illegal. Nonetheless, it is widely accepted that the dividing line between the two is not precise and, from an economic point of view with legal considerations apart, both tax avoidance and tax evasion have similar effects on the national budget, namely, a reduction of government revenue yields.

[44] Ibid.

[45] See footnote 29 on page .

[46] Ibid. See also: “Report on abuse of charities for money-laundering and tax evasion”, OECD, 2009, https://www.oecd.org/tax/exchange-of-tax-information/42232037.pdf.

[47] The rule against perpetuities is a common legal rule in many trust law countries and requires that trusts be settled within a defined period of time and cannot exist in perpetuity or far beyond the lifetimes of the people living at the point of creation.

[48] Self-settled trusts are often criticised for not adhering to the fundamental purpose of trusts i.e. to divest the ownership of assets for the benefit of a third party. For more details, see: Knobel, “‘Trusts: Weapons of Mass Injustice?’ A response to the critics”, 32; Worthy, “Don’t take it on trust”, 7-8.

[49] Worthy, “Don’t take it on trust”.

[50] These “family members” include Prince Jefri’s wife, the issue of Prince Jefri and the issue of the parents of Prince Jefri, as well as Prince Jefri’s descendants and his parents’ descendants.