Defining and capturing information on the beneficial ownership of listed companies

Policy and regulatory framework for beneficial ownership transparency for listed companies

International framework

Beneficial ownership definitions

When creating the legal definition of the BO of legal persons that sets out which criteria qualify an individual as a beneficial owner and require the disclosure of their details to a central register, jurisdictions often follow the requirements and definition of the FATF. In addition, obliged entities, such as financial institutions and other relevant businesses and professions, are required under AML regulations in many jurisdictions to identify the beneficial owners of corporate vehicles as part of KYC and CDD checks. The FATF’s Recommendation 10 requires applying a cascading three-step approach in order to identify a beneficial owner of a legal entity:

- first, by identifying the natural person who has controlling ownership;

- second, if the ownership interests are so diversified that there are no natural persons exercising control of the legal person, by verifying the identity of the natural persons (if any) exercising control through other means; and

- third, where no natural person is identified via any of the above means, by identifying and taking reasonable measures to verify the identity of the relevant natural person who holds the position of senior managing official. [33]

The FATF Recommendations clearly state that this approach does not amend or supersede the definition of who the beneficial owner is, but only sets out how CDD should be conducted by AML-regulated entities in situations where the beneficial owner cannot be identified.

Challenges in applying the anti-money laundering framework to identify beneficial owners of listed companies

When applying the BO definition of legal persons to PLCs to identify their beneficial owners, several difficulties and complications can emerge. For example, due to the distribution of ownership and the prevalence of intermediaries, for most PLCs it will be difficult to identify individuals who meet the common BO criteria of having, directly or indirectly, 25% or more shares or voting rights. As a result, in most cases, even if PLCs are required to disclose their BO to a central register, it is likely that it is practically impossible to comprehensively establish whether any individual may meet the criteria through multiple indirect shareholdings, so no individual is identified as beneficial owner. In the context of CDD, whilst applying the third test in the cascading approach, the senior managing officials of a PLC, such as a chief executive officer (CEO), would be identified as a beneficial owner, even though they may be more an employee than an individual with ultimate control. In some jurisdictions, employees, including senior management, are explicitly excluded from the definition of BO for reporting requirements to central registers. [34]

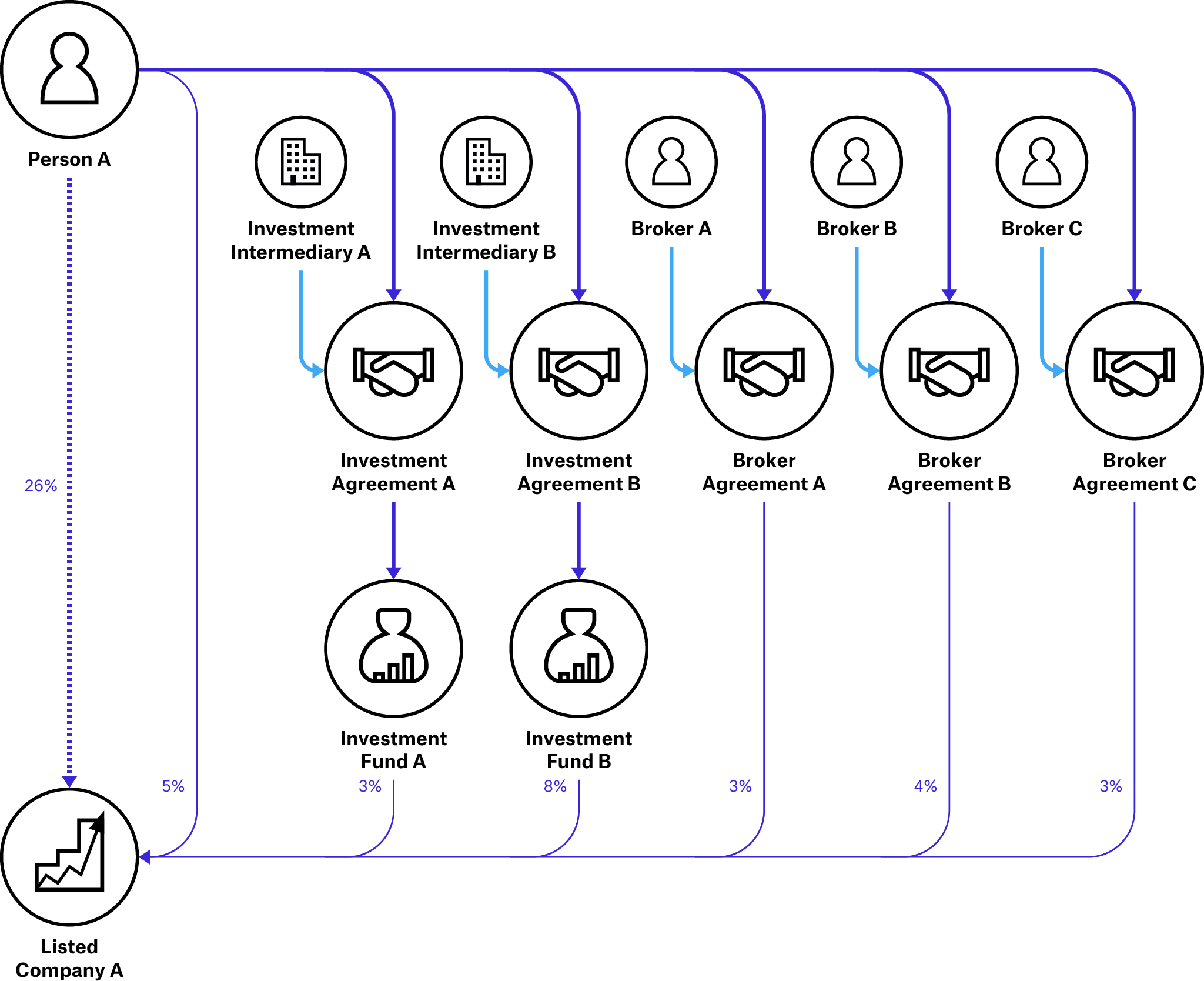

Despite the above challenges in identifying the BO of PLCs, there are many ways in which natural persons can in fact exercise ownership or control over a PLC. As discussed above, in a PLC, an investor may hold interests directly or indirectly through a broker or a financial intermediary. There is also a possibility that an investor may hold interests in a pooled investment fund, which in turn holds interests in shares of a PLC, making it difficult to identify that person as a beneficial owner (see Figure 1). Given their prevalence in PLCs’ ownership structures, BOT requirements for investment funds should be considered alongside transparency in the ownership and control of PLCs. [35]

Figure 1. Beneficial ownership through multiple indirect interests

Person A owns 5% of Listed Company A directly, and indirectly owns a 10% share in the same PLC through Broker A, Broker B, and Broker C, and 11% through Investment Fund A and Investment Fund B. Altogether, Person A thus owns 26% of the PLC’s shares and should be identified as a beneficial owner. However, because their interests are held through various intermediaries, it is difficult to identify Person A as a beneficial owner.

Nominee shareholders

The use of nominee shareholders makes the ownership and control structures of PLCs more complicated. For instance, an everyday investor might own shares in a PLC indirectly through consumer banks, or nominee companies established by wealth managers may collectively hold all or the majority of the shares in a listed company on behalf of their clients. [36] In the latter case, a wealth manager acts as an intermediary. The true beneficiaries can be high-net-worth individuals and family offices, a type of private investment vehicle that is relatively unregulated, and often not named in public shareholder registers. Whilst this is not necessarily problematic, it could also be abused to hide the ownership of family-owned listed companies, for example enabling them to hide their conflict of interest if they also hold management positions or serve on the board of directors (see, for example, Box 6). [37]

Disclosure requirements to central beneficial ownership registers

In international AML policy and regulatory frameworks, PLCs are generally treated as lower risk and are therefore excluded or exempt from disclosure to a central BO register. [38] The FATF does not explicitly require the collection of the BO of PLCs by authorities, but the measures taken do need to respond to identified risks. Information held by stock exchanges is considered part of supplementary measures, alongside a central BO register. [39] Depending on the disclosure requirements of the stock exchange, PLCs may be considered low risk.

However, to rely on stock exchanges as a means of providing additional supplementary information on beneficial owners of companies, countries are required to “consider the extent to which exchanges have processes in place in order to determine the accuracy of basic and beneficial ownership information”. [40] Even in the case of countries that have already established or are in the process of establishing BO registers, this is an important consideration when granting an exemption to PLCs. Furthermore, the use of different definitions of BO and BI for PLCs by some stock exchanges and their regulators raises the question of whether they would be fully compliant with the spirit of this requirement even where BO information is available (see Box 3 above).

The EU’s fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD4) allowed member states to have exemptions from BO disclosure requirements for “a company listed on a regulated market that is subject to disclosure requirements consistent with Union law or subject to equivalent international standards which ensure adequate transparency of ownership information”. [41] For instance, Ireland’s 2019 AML regulations exempt listed companies from maintaining and reporting their BO information to a central register on this basis. [42] The EU’s 2024 AML package, expected to be formally adopted in April 2024, suggests that the criteria for exemptions will become stricter, and that exemptions will only apply to PLCs where “control over the company is exercised exclusively by the natural person with the voting rights” and “no other legal persons or legal arrangements are part of the company’s ownership or control structure”. [43] This suggests the BI information disclosed about active shareholders where these were legal entities or legal arrangements may have been insufficient. Time will tell how these rules will be applied in practice. The latest draft of the EU’s 2024 AML Regulation states that:

[The EU] introduced strict transparency requirements for companies whose securities are admitted to trading on a regulated market. In certain circumstances, those transparency requirements can achieve an equivalent transparency regime to the beneficial ownership transparency rules set out in this Regulation. This is the case when the control over the company is exercised through voting rights, and the ownership or control structure of the company only includes natural persons. In those circumstances, there is no need to apply beneficial ownership requirements to those listed companies. The exemption for legal entities from the obligation to determine their own beneficial owner and to register it should not affect the obligation of obliged entities to identify the beneficial owner of a customer in customer due diligence when performing customer due diligence [emphasis added].

Neither the FATF nor the EU suggest that the companies listed on the stock exchange do not have beneficial owners or that there is no need for listed companies or others to identify their beneficial owners, but rather that sufficient information should be available elsewhere. It follows that PLCs should only be excluded or exempt from BO disclosure requirements when they are listed on a stock exchange that itself has adequate disclosure requirements and transparency measures. [45] These requirements and measures differ, and providing a blanket exemption to PLCs without assessing the stock exchange where they are listed would thus not be in line with the intent of international standards. The EU appears to go even further and set exemptions not just based on the transparency and disclosure requirements of stock exchanges and regulators, but also on the ownership and control structures of the PLCs themselves. [46] In addition, to easily find relevant information held in exchanges for different PLCs, a number of civil society organisations argue that some information should still be collected centrally for PLCs. [47]

Customer due diligence requirements

The FATF also states that it is not necessary to identify and verify the identity of any shareholder or beneficial owner of a PLC which is “listed on a stock exchange and subject to disclosure requirements (either by stock exchange rules or through law or enforceable means) which impose requirements to ensure adequate transparency of beneficial ownership.” [48] This exclusion or exemption is, however, largely based on the assumption that the financial regulator or a stock exchange where an exempt company is listed would have adequate and appropriate transparency and disclosure requirements over individuals who own or control the entity. [49] However, disclosures to a stock exchange are often not verified or verifiable due to the challenges mentioned earlier. This means that disclosure requirements for PLCs may rely fully on self-reporting and may not be subject to external checks and verification.

Evidence suggests that where jurisdictions have previously excluded other types of corporate vehicles from disclosure requirements, this has displaced risk and these have become more attractive for misuse. [50] In addition to AML, this exclusion or exemption may not be appropriate for other policy aims, including protecting other shareholders (see Box 6).

Gaps in international frameworks

A prominent gap in the international frameworks is the lack of clarity about how much of a company’s equity needs to be listed on an exchange with sufficient disclosure and transparency requirements for it to be exempt from BO disclosure requirements. This gap might have significant implications because a company may, for example, list only 5% or less of its shares on such an exchange and nevertheless still qualify for full exemption. An exchange may then only require BO disclosure for this small proportion of listed shares and not impose sufficient disclosure requirements about the ownership and control of the unlisted shares. Some or all of the rest of the shares could also be listed on another exchange, with different or low disclosure and transparency requirements.

Implementers can try to assure the transparency of the unlisted shares of a listed company through a number of approaches. For instance, stock exchanges can be required to strengthen disclosure requirements for unlisted shares, or PLCs could be required to disclose the BO of unlisted shares to a central register. The transparency requirements of stock exchanges for unlisted shares requires further research and analysis. In the UK, for instance, unlisted or certificated shares of exempt PLCs are not subject to either BI or BO disclosure to either the central BO register or the stock exchange. [51] This also appears to be the case in the US, where the 5% BO reporting threshold only applies to listed shares.

This further highlights the importance of assessing the disclosure and transparency requirements imposed by individual stock exchanges, and using that as a basis for exemptions. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), for instance, encourages national multi-stakeholder groups to review the comprehensiveness, reliability, and availability of ownership information disclosed on stock exchange filings to ensure the quality of information on ownership and control disclosed by PLCs. [52] A number of recent studies have also further identified that the BO information collected by stock exchanges is not always adequate, accurate, or up to date. [53] Additionally, there is a possibility that the information kept by a stock exchange may be poorly structured, poorly formatted, or not easily accessible to all relevant parties. [54]

As covered above, the term BO as understood and used by a stock exchange may not always be the same as it is defined in the international standards. The following section on national frameworks explores whether BI information comprises sufficiently useful and usable information about who owns, controls, and benefits from PLCs, and whether it is more practically feasible to comply with than BO disclosure. Whilst it does not necessarily include the identification of a natural person, a PLC failing to identify a beneficial owner may potentially disclose less information than one that is complying with BI disclosure. Moreover, where corporate vehicles hold BI in a PLC, information about their BO may be available in a central register, in cases where it is not exempt – which is often the case for investment funds – or based in a jurisdiction that has not effectively implemented BOT reforms.

A study examining the accessibility of PLCs’ BO information in seven Asian countries highlighted that in several countries, the mandatory BO reporting by PLCs has merely become a box-ticking exercise, leading to only minimally compliant disclosures that fail to meet the intended regulatory objectives. [55] The report emphasises that ownership and control structures of the majority of PLCs are not adequately disclosed in an accessible way.

The majority of stock exchanges and securities regulators mainly focus on outlining rules and regulations, and providing references and links to the annual reports of listed companies where BO information can be found. [56] However, finding BO information in annual reports, which can be hundreds of pages long, can be a time-consuming exercise. Accessing, interpreting, or inferring BO information of listed PLCs from some stock exchanges can require expertise or local knowledge due to the technical style of presenting information, without any charts or graphs. [57]

Separate guidance from Open Ownership includes some early thinking on factors that should be considered by policymakers when creating a list of stock exchanges for which listed companies could be exempt. [58] These factors include:

- timely notification on the acquisition and disposal of significant voting rights;

- notifications on the basis of aggregated holdings and interests used jointly via an agreement;

- notifications of ownership and control arrangements via financial instruments that have a similar effect to owning shares or controlling votes;

- notifications that contain information on the means through which major shareholding or voting rights are exercised (for example, the chain of ownership);

- notifications of interests held by company officers;

- information on who has access to this information, whether it is easily accessible or there are any conditions, the format in which it is available, and whether information storage policies are adequate.

International standards could be extended to include clear criteria on how to set exemptions, including how to assess disclosure and transparency requirements of stock exchanges and regulators, and requiring information on exempt PLCs to be centralised. The divergence of how international standards are applied is explored in the following section.

National frameworks

Jurisdictions around the world, often applying a risk-based approach, have taken significantly different approaches in implementing BOT requirements for PLCs. Generally, the approaches range from applying the same requirements to PLCs as to other legal entities, to fully excluding PLCs from BO disclosure requirements. PLCs are one of the categories of corporate vehicles that are most commonly exempt from full BO disclosure requirements or otherwise excluded from BOT regimes altogether.

Generally, the approaches taken by jurisdictions differ in terms of which PLCs are subject to disclosing what information and to whom. For example, PLCs may be required to disclose either BI or BO information to a regulator or stock exchange, or to make information directly available through their website or quarterly or annual reports. On this basis, they may be required to disclose less or no information to a central BO register. There may also be differences in whom reporting requirements fall upon – the party holding the interest, or the PLC itself. The following section explores different national approaches using examples from different jurisdictions.

Information to be disclosed

Beneficial ownership and beneficial interest

In many countries, PLCs are required to disclose BI information, either to the stock exchange – as in South Africa (see Box 7) – or to the regulator. For example, in Canada, disclosure requirements for PLCs include shareholders with direct or indirect control over more than 10% of the company’s equity or voting rights to the Canadian Securities Administrators within two days of acquisition. [59] These can be either natural persons or companies.

In some jurisdictions, PLCs are required to disclose BO information. For example, in India, whilst listed companies are exempt from BO disclosure to the central register, the securities regulator implemented specific BO requirements for listed companies in 2018, using the exact same BO definition as for the central register in the Companies Act, stating that “all the terms [...] shall have the same meaning as specified in [the] Companies (Significant Beneficial Owners) Rules, 2018”. [60] The timeframe for disclosure is also the same for PLCs as for private companies: a total of 60 days to report BO information or any changes to the BO information. However, PLCs are required to make BO information available in their quarterly reports. [61]

When looking at jurisdictions that require PLCs to disclose BO information, whilst these requirements are arguably more stringent than requiring BI information, in practice this approach may run the risk of generating little to no information on ownership and control (see, for example, Box 8). Conversely, jurisdictions that require the disclosure of BI information appear to collect more useful information (see Box 7). When BO information is disclosed by PLCs in jurisdictions where this is required, the information seems to be of a type and nature that would be captured under the definition of BI, for example, direct shareholdings or voting rights, although it does not extend to natural persons.

Box 7. In-depth case study of the disclosure requirements for listed companies in South Africa [62]

In order to comply with international AML standards, South Africa legislated for central BO registers for a number of corporate vehicles through the 2022 General Laws (Anti-Money Laundering and Combating Terrorism Financing) Amendment Act (GLAA). [63] In the legislation, a public company is considered an affected company under section 117(1)(i) of the Companies Act, making it subject to different disclosure requirements than regular companies. [64] Listed companies are obliged to maintain a BI register and file it with the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC), as prescribed in regulations. [65] However, a public company that is listed on a South African stock exchange is exempt from filing its BI register with the CIPC, provided such information is already kept at a stock exchange or any other institution with the authority to collect and keep such records. The concept of BI existed in South African legislation before the GLAA, and applied to all companies in terms of the Companies Act of 2009 as amended. During the passage of the act, the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE), among others, voiced serious concerns about being able to comply with BO disclosure and proposed central BI disclosure as an alternative.

The law makes a clear distinction between BI and BO. A beneficial owner of a legal person is mainly defined as meaning a natural person who, directly or indirectly, ultimately owns a company or exercises effective control over a company, using a threshold of 5%. [66] On the other hand, the definition of BI refers to either legal persons or natural persons who receive or participate in any distribution in relation to the company’s securities; exercise any attaching rights to these securities; or can dispose or direct the disposition of the company’s securities, such as a nominator in a nominee arrangement. [67] BO therefore includes, and is much broader than, the concept of BI.

According to a representative from the JSE, PLCs in South Africa are exempt from reporting their BO information because, first, it is challenging for them to identify their beneficial owners and thus to practically comply with BO reporting requirements. Second, adequate transparency measures are already in place to provide information on BI holders in a listed company, which will be useful in the identification of the beneficial owners of a PLC when such information is required by competent authorities.

On the identification and reporting of BO information by PLCs, the JSE also notes that this is particularly difficult and complex for PLCs due to the reasons already outlined in this briefing. These include, for instance: a large number of PLCs’ shareholders are often dispersed across several geographical locations worldwide; the structure of registers in South Africa – shares are often held by nominees as registered shareholders, and there is no direct connection between shareholders and the company; and the nearly daily changes in the shareholding of listed companies.

In terms of transparency and disclosure requirements for listed companies, South Africa appears to be setting a good example despite some challenges related to foreign nominees. Based on information from a JSE representative and other public information, a listed company in South Africa is required to maintain a register of all BI holders under the Companies Act. [68] An obligation is also placed on registered shareholders to disclose to the listed company the identity of the natural or legal persons on whose behalf any securities are held in the listed company at regular intervals – almost on a weekly basis. [69] The JSE representative emphasised that this disclosure by registered shareholders who are acting as nominees provides significant transparency of listed securities, down to the level of BI holder. Through these disclosures, a PLC will know at regular intervals who all of its BI holders are. In addition, companies acting as nominees in South Africa are also required to be licensed and approved by the Financial Sector Conduct authority. Moreover, exchanges also license nominee companies as brokers.

The Companies Act also places an obligation on any person who acquires or disposes of a significant percentage of BI in a listed company to disclose this to the company, including the extent of their BI, within three days. [70] The threshold for this disclosure is currently set at 5% of the issued securities and increases in 5% increments. As a result, anyone who acquires or disposes of 5% or more shares in a listed company is required to disclose this information, which is in addition to the obligation placed on nominee shareholders to disclose the identity of the BI holder on whose behalf they hold securities.

PLCs are required to publish the identity of all persons who hold 5% or more of BI in their annual financial statements. [71] JSE listing rules also require PLCs to publish the information on significant BI holdings that has been disclosed to the company. [72] When any BI holder acquires or disposes of 5% or more of shares, all other shareholders have to be notified and the information made public within 48 hours. Any changes are also required to be reported to the JSE.

The existing transparency and disclosure requirements implemented for listed companies in South Africa, through a combination of the Companies Act and JSE listing rules, are considered by the JSE to provide timely public disclosure of information about all significant BI holders. This information also aids competent authorities in identifying beneficial owners when required. [73] For instance, in the case of the disclosure of legal persons as BI holders, competent authorities have to conduct further investigation to collect the relevant information about their beneficial owners. This information can be obtained from the CIPC in the case of legal persons incorporated in South Africa, as they are required to disclose their BO information to the CIPC. However, it is more difficult when dealing with foreign legal persons, particularly in those jurisdictions where BO registries do not exist or the information is inaccessible.

The JSE representative also highlighted the challenges with foreign companies acting as nominees, which fall outside the scope of legislation and South African jurisdiction. They are not required to identify themselves as nominees to the company, meaning foreign nominee shareholders may be viewed as BI holders. Overall, however, the JSE affirms the granting of exemption to PLCs from the BO disclosure requirements in view of the difficulties PLCs encounter in identifying and disclosing their beneficial owners as well as the transparency and disclosure requirements placed on South African listed companies. These requirements are practically feasible for PLCs and ensure relevant ownership information beyond legal ownership is available in a timely fashion.

Which party has a mandate to collect information

Jurisdictions require disclosure to one or more of the following parties: the central BO register, the regulator, the stock exchange, or directly to the public. For example, in India, PLCs are required to disclose BO information to the regulator, as well as to the public in quarterly reports on their own websites. This means that for the public, access to information is not centralised, may be time consuming to find, and is not available in a structured format. In Canada, BI information is collected by the regulator. In South Africa, BI information is collected by the regulator unless it is already disclosed and published by a domestic stock exchange, and significant BI holdings are also published in annual reports. In the UK, BI information is collected by the regulator, and all PLCs are also subject to BO reporting to the central BO register, although exempt PLCs do not need to disclose their BO (see Box 8).

Which listed companies are subject to disclosure

PLCs are typically exempt from BO disclosure regimes on the grounds that they are subject to extensive reporting and disclosure requirements about ownership and control that in some ways exceed the BO reporting requirements for privately owned companies and other corporate vehicles. Often, this is on the basis that the information discussed above is already disclosed in some form to another party. However, the level of transparency over the ownership of PLCs varies between jurisdictions and among stock exchanges, making it difficult in certain cases to obtain and access adequate, accurate, and up-to-date information on ownership and control of listed companies. Countries can exempt PLCs either explicitly or implicitly from the BO registration framework. [74]

Inclusion

A number of countries have either explicitly covered or have not explicitly excluded PLCs from their BO regime. [75] In Albania, for instance, since companies listed on a stock exchange are not explicitly excluded from the BO registration law (No. 112/2020), it is assumed that they are covered within the BO disclosure requirements. However, looking at various random entries of listed companies on the Albanian BO register, many BO statements for listed companies appear to be inaccurate or illogical. [76] For instance, the BO statement for a listed bank includes the names of its CEO and vice-chair as both having 0% indirect ownership.

Exemption based on stock exchanges or their jurisdictions

Exemptions are often made on the basis of the jurisdictions of the stock exchange (or exchanges) through which the PLC has listed its shares, as the regulatory environments determine the disclosure requirements for the PLC. For example, in Germany, a PLC listed in the country or another jurisdiction within the European Economic Area (EEA), or subject to equivalent transparency requirements, is not required to disclose information to the BO register. [77] German PLCs are subject to the disclosure requirements on major shareholdings and voting rights, and any changes therein, under the EU AMLDs, as explained above. In the UK, for instance, the FCA has exempted the companies listed on the LSE from the BO disclosure requirements, as it is subject to similar requirements as in the EU as a regulated market. However, no such exemption is applicable to companies listed on the AIM, as it is subject to the same disclosure requirements as the LSE’s Main Market and not classed as a regulated market (Box 8).

Some jurisdictions, like South Africa (see Box 7) and Kenya exempt PLCs listed in domestic exchanges. [78] The British Virgin Islands exclude any exchange listed on the World Federation of Exchanges, and specific designated exchanges. [79]

Box 8. Exemption and compliance with disclosure by listed companies in the United Kingdom

The UK’s 2017 People with Significant Control (PSC) (Amendment) Regulations exempt the following PLCs from maintaining and disclosing their BO information on the PSC register:

a) companies with voting shares admitted to trading on a regulated market which is situated in a EEA state (for example, the LSE Main Market); and

b) companies with voting shares admitted to trading on certain specified markets in Israel, Japan, Switzerland, and the US (under listed markets in Schedule 1 of the regulations). [80]

From 26 June 2017, UK-incorporated public companies with shares admitted to trading on a prescribed market – including the AIM segment of the LSE or the NEX Exchange Growth Market – are no longer exempt from BO disclosure requirements to the PSC register, unless they have multiple listings and also fall within one of the two exemptions listed above. This is due to the fact that AMLD4 only permitted the exemption of regulated markets and not prescribed markets. [81] These listed companies are required to: make reasonable investigations as to their beneficial owners; produce and make their BO information public; and comply with the ongoing obligations to make all the requisite filings with the registrar, Companies House. This is because the entry criteria for AIM are lower: for example, making it possible to gain admission without a trading record, which allows newer companies that are looking for a stepping stone into the regulated market to benefit from a more flexible regulatory environment in the interim. [82]

AIM’s rules for companies include Rule 26, which requires certain information to be published on “a website”, including information about significant shareholders, which must be updated every six months, and the percentage of shares not publicly traded. [83] Significant shareholders are defined as “Any person with a holding of 3% or more in any class of AIM security”. [84] These can be individuals, companies, and investment funds, or an entire family. [85] This appears to be less stringent than the disclosure requirements of regulated markets.

Looking at UK-registered companies that are listed on the AIM provides an opportunity to study the type of information available when BO requirements are applied to PLCs, particularly because the UK company registrar makes structured data available in bulk. Looking at a sample of 600 of the 649 companies listed on the AIM, 393 of these are registered in the UK and active, and are therefore subject to BO disclosure requirements. [86] Of these 393 companies, 266 (68%) report that, “The company knows or has reasonable cause to believe that there is no registrable person or registrable relevant legal entity in relation to the company”. A further 41 claim an exemption, either because they claim to be listed on an EU regulated market (4) or a UK regulated market (37). Based on a review of all individual company websites, only 2 of the 41 companies claiming an exemption based on being listed on a UK or EU regulated market actually appear to be listed on a regulated market in addition to the AIM. Therefore, a total of 39 appear to be noncompliant in claiming an exemption. There may be a range of reasons for this, including insufficient guidance or a lack of verification.

Another 7 companies in the sample appear to be noncompliant by having made no disclosure statement to the register (2); disclosing a non-UK corporate vehicle (directly or through a relevant legal entity) (4); or disclosing an individual as a company (1). This means that for 309 companies, or 79% of the sample, there is no additional information provided through BO reporting because they have either declared not to have any beneficial owners (266); have claimed an exemption that does not appear valid (39); or are otherwise noncompliant (7). For 81 of the 393 companies in the sample, BO reporting provided information on individuals as beneficial owners, or relevant legal entities which lead to BO statements with individuals or a valid exemption due to dual listing (1). [87]

This suggests that subjecting PLCs to BO disclosure does not necessarily lead to more useful information about ownership and control for all companies. Listing on the AIM does not qualify a PLC for an exemption due to the fact that it has lower disclosure and transparency requirements than the LSE Main Market segment, and AIM-listed PLCs are therefore subject to additional BO disclosure requirements. However, the vast majority of these do not provide any useful or usable information. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that there is less useful information available about PLCs deemed higher risk, and is in fact counterproductive to the intentions of the exemption regime.

Blanket exemptions or exclusion

Some jurisdictions provide blanket exemptions or exclude all companies listed on stock exchanges from disclosure requirements. For example, Finnish guidance states that listed companies are not liable to file a notification of BO. [88] This also appears to be the case in France and Sweden. Given the fact that the transparency and disclosure requirements of exchanges vary significantly, and these requirements can even differ within different segments of an exchange, blanket exemptions are a potential loophole.

Reporting requirements for exempt listed companies

Where exemptions to BO disclosure for PLCs apply, jurisdictions collect different amounts of information from the exempt companies through BO reporting. Some jurisdictions, like Luxembourg, require exempt PLCs to disclose certain minimum information to a central BO register, even if they are exempt from full BO disclosure requirements. This approach helps users find connected and relevant information about ownership and control, and makes BO registers more useful and usable. This is in contrast to other jurisdictions, like Germany, which do not require PLCs to disclose any information to the central BO register, as information on ownership is disclosed elsewhere. In Luxembourg, listed companies whose securities are admitted to trading on a regulated market are excluded from the obligation to provide information regarding their beneficial owner(s) on the Luxembourg Register of Beneficial Owners (Registre des Bénéficiaires Effectifs, or RBE). Nevertheless, they must disclose the name of the regulated market on which their securities are admitted to the RBE, thereby making it easier to find relevant information. [89]

Similarly, in Mongolia, listed companies are exempt from reporting their BO information to the General Authority for State Registration (GASR). However, they are required to disclose information to the GASR about the proportion of shares listed; the names of the stock exchanges; and a link to the relevant stock exchange website pages, with details of the company listing and other relevant details. [90] Nigeria also requires PLCs to disclose the name of the stock exchange and to provide a link to the stock exchange filings where they are listed. [91] In the UK, the general basis for exemption is collected and published, but not any additional information about where relevant information can be found.

Finally, the 2023 EITI Standard also takes this approach. It does not explicitly exempt PLCs from BOT disclosure requirements, but requires that PLCs, including wholly owned subsidiaries, disclose the name of the stock exchange and include a link to the stock exchange filings where they are listed to facilitate public access to their ownership and control information. [92]

Footnotes

[33] FATF, “Interpretive Note to Recommendation 10 (Customer Due Diligence)”, International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism and Proliferation: The FATF Recommendations (Paris: FATF, 2012-23), 67-68, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/recommendations/FATF%20Recommendations%202012.pdf.coredownload.inline.pdf.

[34] For example, in the US. See: Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, Department of the Treasury, “Beneficial Ownership Information Reporting Requirements”, US Federal Register, 20 September 2022, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/09/30/2022-21020/beneficial-ownership-information-reporting-requirements.

[35] Chhina and Markle, Defining and capturing information on the beneficial ownership of investment funds.

[36] Ramandeep Chhina, Beneficial Ownership Transparency in Asia and the Pacific (Manila: Asian Development Bank, 2022), 44, http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/TCS220565.

[37] OECD, Beneficial Ownership Disclosure in Asian Publicly Listed Companies, 11.

[38] FATF, FATF Recommendations, 71.

[39] FATF, FATF Recommendations, 95.

[40] FATF, Beneficial Ownership of Legal Persons (Paris: FATF, 2023), 91, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/guidance/Guidance-Beneficial-Ownership-Legal-Persons.pdf.coredownload.pdf.

[41] European Union Law, “Directive (EU) 2015/849 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2015 on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing, amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Directive 2005/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Directive 2006/70/EC”, Official Journal of the European Union, EUR-Lex, 20 May 2015, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32015L0849.

[42] Ministry of Finance, “Statutory Instruments – S.I. No. 110 of 2019 – European Union Anti-Money Laundering: Beneficial Ownership of Corporate Entities) Regulations 2019”, Regulation 4, 22 March 2019, https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2019/si/110/made/en/pdf (now amended as: Ministry of Finance, “Statutory Instruments – S.I. No. 308 of 2023 – European Union (Anti-Money Laundering: Beneficial Ownership of Corporate Entities) (Amendment) Regulations 2023”, 16 June 2023, https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2023/si/308/made/en/pdf).

[43] General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union, “Proposal for a Regulation of the European Union Parliament and of the Council on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing”, European Council, 13 February 2024, 257, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-6220-2024-REV-1/en/pdf.

[44] General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union, “Proposal for a Regulation of the European Union Parliament and of the Council on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing”, 76.

[45] Kadie Armstrong and Jack Lord, Beneficial ownership transparency and listed companies (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2020), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/beneficial-ownership-transparency-and-listed-companies/.

[46] General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union, “Proposal for a Regulation of the European Union Parliament and of the Council on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing”, 257.

[47] See, for example: Armstrong and Lord, Beneficial ownership transparency and listed companies; and Markle, Coverage of corporate vehicles in beneficial ownership disclosure regimes.

[48] See: FATF “Interpretive Note to Recommendation 10”, FATF Recommendations, 68; and Article 3(6) of the EU AMLD4.

[49] See: FATF, “Interpretive Note to Recommendation 10”, FATF Recommendations, 68, which states: “Where the customer or the owner of the controlling interest is a company listed on a stock exchange and subject to disclosure requirements (either by stock exchange rules or through law or enforceable means) which impose requirements to ensure adequate transparency of beneficial ownership, or is a majority-owned subsidiary of such a company, it is not necessary to identify and verify the identity of any shareholder or beneficial owner of such companies”. A similar provision is contained under Article 3(6) of the EU AMLD4 which provides that: “‘beneficial owner’ means any natural person(s) who ultimately owns or controls the customer and/or the natural person(s) on whose behalf a transaction or activity is being conducted and includes at least: (a) in the case of corporate entities: (i) the natural person(s) who ultimately owns or controls a legal entity through direct or indirect ownership of a sufficient percentage of the shares or voting rights or ownership interest in that entity, including through bearer shareholdings, or through control via other means, other than a company listed on a regulated market that is subject to disclosure requirements consistent with Union law or subject to equivalent international standards which ensure adequate transparency of ownership information”.

[50] Markle, Coverage of corporate vehicles in beneficial ownership disclosure regimes, 8-9.

[51] See: “Ownership, control, or influence? UBOs and further complications”, The Dark Money Files, Podcast Episode, 19:27 mins, September 2023, https://open.spotify.com/episode/78N5J4RPr0CqZEkzSZo7pz?si=e340e80fffe24795.

[52] EITI, “Requirement 2.5 f)”, EITI Standard 2023 (Oslo: EITI, 2023), 20, https://eiti.org/collections/eiti-standard.

[53] See, for example: OECD, Beneficial Ownership Disclosure in Asian Publicly Listed Companies.

[54] Markle, Coverage of corporate vehicles in beneficial ownership disclosure regimes, 13.

[55] OECD, Beneficial Ownership Disclosure in Asian Publicly Listed Companies, 21.

[56] OECD, Beneficial Ownership Disclosure in Asian Publicly Listed Companies, 20.

[57] OECD, Beneficial Ownership Disclosure in Asian Publicly Listed Companies, 22.

[58] See: Armstrong and Lord, Beneficial ownership transparency and listed companies, 5-6; Markle, Coverage of corporate vehicles in beneficial ownership disclosure regimes, 13.

[59] Andrea Hill, “Spotlight On: Crossing the 10% Ownership Threshold”, SkyLaw, 15 January 2022, https://www.skylaw.ca/2022/01/15/spotlight-on-crossing-the-10-ownership-threshold/.

[60] Securities and Exchange Board of India, “Circular No. SEBI/HO/CFD/CMD1/CIR/P/2019/36 – Modification of circular dated December 7, 2018 on Disclosure of significant beneficial ownership in the shareholding pattern”, 12 March 2019, https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/circulars/mar-2019/modification-of-circular-dated-december-7-2018-on-disclosure-of-significant-beneficial-ownership-in-the-shareholding-pattern_42324.html; Securities and Exchange Board of India, “Circular No. SEBI/HO/CFD/CMD1/CIR/P/2018/0000000149 – Disclosure of significant beneficial ownership in the shareholding pattern”, 7 December 2018, https://www.cse-india.com/upload/upload/SEBI_CIRCULAR_07122018.pdf.

[61] See, for example: Shareholding Pattern, ASHOKAMET, 30 September 2023, http://www.ashokametcast.in/Reports/Shareholding%20Pattern/SHP_30.09.2023.pdf.

[62] This case study draws heavily on a remote, video conference interview with a representative from the JSE on 13 October 2023, and is mentioned throughout.

[63] Parliament of the Republic of Africa, General Laws (Anti-Money Laundering and Combating Terrorism Financing) Amendment Act, No. 22 of 2022, adopted 29 December 2022, https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202212/47815anti-moneylaunderingact22of2022.pdf.

[64] An “affected company” is a regulated company as set out in section 117(1)(i) of the Companies Act and a private company that is controlled by a subsidiary of a regulated company as a result of any circumstances contemplated in section 2(2)(a) or 3(1)(a). Affected companies include: a public company; a state-owned company; a private company – in terms of the transfer of securities when exceeding the percentage prescribed by a Minister (10%) within a 24-month period; a private company that is controlled by an affected company (regulated company) or is a subsidiary of an affected company. Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, Companies Act 2008, No. 71 of 2008, adopted 9 April 2009, Section 1, https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/321214210.pdf.

[65] Republic of South Africa, Department of Trade, Industry, and Competition, Companies Amendment Regulations 2023, No. R. 3444, adopted 24 May 2023, https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202305/48648rg11585gon3444.pdf.

[66] The CIPC Guidance Note 2 of 2023 on BO filing requirements defines “beneficial owner” in respect of a company as: “an individual who, directly or indirectly, ultimately owns that company or exercises control of that company, including through – (a) the holding of beneficial interests in the securities of that company; (b) the exercise of, or control of the exercise of the voting rights associated with securities of that company; (c) the exercise of, or control of the exercise of the right to appoint or remove members of the board of directors of that company; (d) the holding of beneficial interests in the securities, or the ability to exercise control, including through a chain of ownership or control, of a holding company of that company; (e) the ability to exercise control, including through a chain of ownership or control, of – (i) a juristic person other than a holding company of that company; (ii) a body of persons corporate or unincorporate; (iii) a person acting on behalf of a partnership; (iv) a person acting in pursuance of the provisions of a trust agreement; or (f) the ability to otherwise materially influence the management of that company”.

[67] Section 1 of the Companies Act 2008 states that “when used in relation to a company’s securities[,] 'beneficial interest' means the right or entitlement of a person, through ownership, agreement, relationship or otherwise, alone or together with another person to— (a) receive or participate in any distribution in respect of the company’s securities; (b) exercise or cause to be exercised, in the ordinary course, any or all of the rights attaching to the company’s securities; or (c) dispose or direct the disposition of the company’s securities, or any part of a distribution in respect of the securities, but does not include any interest held by a person in a unit trust or collective investment scheme in terms of the Collective Investment Schemes Act, 2002 (Act No. 45 of 2002).“ Companies Act 2008, Section 1.

[68] Companies Act of 2008, Section 56.

[69] Companies Act of 2008, Section 56.

[70] Companies Act of 2008, Section 122.

[71] Companies Act of 2008, Section 56; JSE, “JSE Limited Listing Requirements”, LexisNexis, Section 8.63, https://www.jse.co.za/sites/default/files/media/documents/2019-04/JSE%20Listings%20Requirements.pdf.

[72] JSE, “JSE Limited Listing Requirements”, Section 3.83.

[73] JSE Submission to the Parliament on the General Laws (Anti-Money Laundering and Combatting Terrorism Financing) Amendment Bill, 10 October 2022, 7.

[74] See: KPMG, UBO disclosure requirements within the EU (s.l.: KPMG International, 2019), https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2018/07/gls-transparency-register-web.pdf. Other countries that have exempted PLCs from BO disclosure include: Brazil, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Isle of Man, North Macedonia, Malaysia, Morocco (only required to declare the name of the regulated market in question), the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and the UK (for companies listed on the LSE Main Market).

[75] For example, Argentina, Albania, Canada, Colombia, Czech Republic, Moldova, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, and Portugal.

[76] Qendra Kombëtare e Biznesit (National Business Centre), “Reporting Subject”, Search Page, Register of Beneficial Owners, n.d., https://qkb.gov.al/search/search-in-the-register-of-beneficial-owners-rbo/search-reporting-subject/.

[77] Germany, BaFin, Geldwäschegesetz - Money Laundering Act, adopted on 12 October 2018, s. 3(2), https://www.bafin.de/SharedDocs/Veroeffentlichungen/EN/Aufsichtsrecht/Gesetz/GwG_en.html;jsessionid=335EA653108506CA352113E5D2836507.internet011?nn=19586032#doc19618182bodyText1.

[78] “Beneficial Ownership Newsletter”, Karanja-Njenga Advocates, 14 January 2021, https://knjenga.co.ke/beneficial-ownership-newsletter/.

[79] British Virgin Islands Financial Services Commission, “Regulatory Code, 2009 – Issued under section 41 (1) of the Financial Services Commission Act, 2001”, 2009, 21-22, https://www.bvifsc.vg/sites/default/files/regulatory_code_2009.pdf.

[80] United Kingdom, The Register of People with Significant Control Regulations 2016, No. 339, adopted on 15 March 2016, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2016/339/contents/made.

[81] Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), Implementation of the Fourth Money Laundering Directive – Discussion paper on the transposition of Article 30: beneficial ownership of corporate and other legal entities (London: BEIS, 2016), 21, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/565095/beis-16-38-4th-money-laundering-directive-transposition-discussion-paper.pdf.

[82] “AIM”, Thomson Reuters Practical Law, Glossary, 2024, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/8-107-6392?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default).

[83] LSE, AIM Rules for Companies (London: LSE, 2018), 11-12, https://docs.londonstockexchange.com/sites/default/files/documents/aim-rules-for-companies-march-2018-clean.pdf.

[84] LSE, AIM Rules for Companies, 32.

[85] See, for example: “Shareholder Information”, Design Group, 29 February 2024, https://www.thedesigngroup.com/investors/shareholder-info/.

[86] According to the LSE, 649 companies are listed on the AIM segment on 6 March 2024 (“FTSE AIM ALL-SHARE”, LSE, n.d., https://www.londonstockexchange.com/indices/ftse-aim-all-share/constituents/table). A list of 600 AIM listed companies was used from the investment company Fidelity (“FTSE AIM ALL-SHARE”, Fidelity International, n.d., https://www.fidelity.co.uk/shares/ftse-aim-all-share/), as it was possible to convert this list into structured data for the analysis. The 600 names were matched against the Companies House data using their application programming interface, where these were a 100% match, and manually checked where they were not.

[87] For more information on relevant legal entities, see: BEIS, Register of People with Significant Control – Guidance for People with Significant Control over Companies, Societates Europaeae, Limited Liability Partnerships and Eligible Scottish Partnerships (London: BEIS, 2017), 10-12, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5bd9e31f40f0b604e0b7828c/170623_NON-STAT_Guidance_for_PSCs_4MLD.pdf.

[88] “Which companies file a notification of beneficial owners?”, Finnish Patent and Registration Office, 5 August 2020, https://www.prh.fi/en/kaupparekisteri/beneficial_owner_details/companies.html.

[89] Norton Rose Fulbright, Regulations around the World: Beneficial Ownership Register, (s.l.: Norton Rose Fulbright, 2023), https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/-/media/files/nrf/nrfweb/publications/v3-50108_emea_brochure__regulation-around-the-world---beneficial-ownership-registries.pdf?revision=c8e6fc90-bf31-4999-9698-00cb17a9861a&revision=5249855980737387904.

[90] Michael Barron, Tim Law, Batsugar Tsedendamba, and Ariuntsetseg Jigmeddorj, Beneficial Ownership Transparency in Mongolia: Tackling Complex Implementation Issues (s.l.: Leveraging Transparency to Reduce Corruption, 2022), iii, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/GS_08192022_BeneficialOwnershipTransparencyMongolia.pdf.

[91] Global Forum of Asset Recovery, Guide to Beneficial Ownership Information: Legal Entities and Legal Arrangements (s.l.: Global Forum of Asset Recovery, 2017), 2, https://star.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/bo_country_guide_nigeria.pdf.

[92] EITI, “Requirement 2.5 f)”, EITI Standard 2023, 20.