Modelling beneficial ownership data

Welcome to the first in a series of technical posts about working with beneficial ownership data. Over the past three years, Open Ownership has been building a prototype Global Beneficial Ownership Register, in order to prove the feasibility and value of linking beneficial ownership (BO) data across jurisdictions. We have used this project to experiment with a variety of tools and processes, from standardising data under the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard to providing a search engine, disclosure viewer, data archive and network visualisation (amongst others). As this phase of our work draws to a close, we are documenting the things we have learned and sharing our experiences with data users and publishers in the public and private sector.

This first post covers the fundamental task of modelling beneficial ownership data. We explain the core decisions made in our Beneficial Ownership Data Standard and the foundational modelling decisions these represent. We then explore the choices one needs to make when building a system to store or query BO data. We finish by sharing our own experiences using a variety of database systems and the open BO data available today.

What is Beneficial Ownership Data?

Firstly, what are we talking about when we say ‘Beneficial Ownership Data’? Fundamentally, it is data that describes how companies are owned or controlled. This means it describes three things:

- People, as individual owners

- Legal entities, such as owned companies, intermediate owners or, in special cases, ultimate owners (e.g. with state-owned enterprises)

- The ownership or control relationships and means of control – share percentages, details of voting rights, rules around board membership and so on.

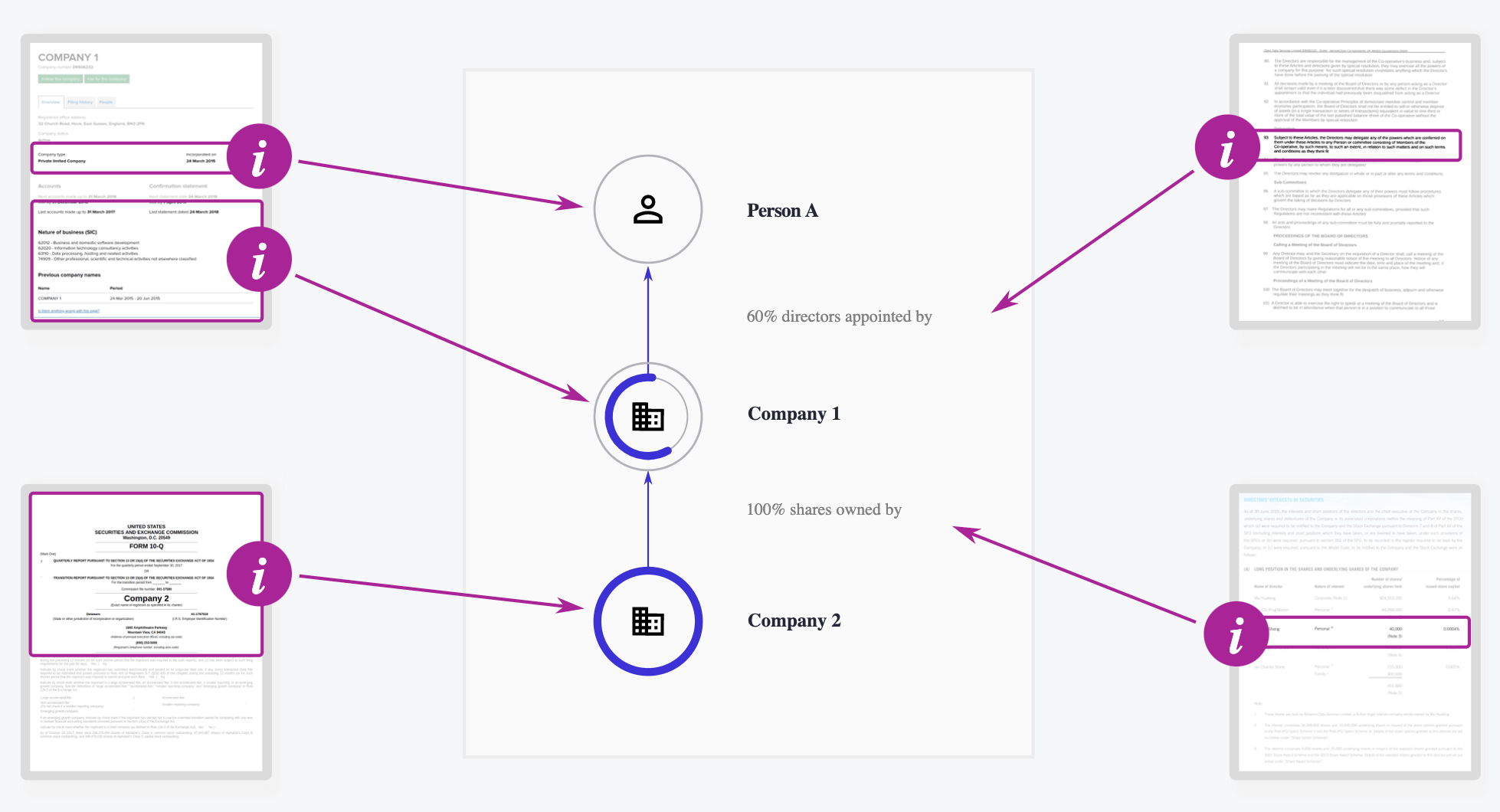

Drawing from our primer on the subject, we know that information describing beneficial ownership is often scattered across documents such as companies’ annual reports, founding articles and filings to regulatory authorities.

Image from the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard documentation, showing how parts of different documents combine to create beneficial ownership data.

Gathering the necessary data can be challenging, but once done it is possible to get a complete picture of a company’s beneficial ownership, realising the benefits for anti-corruption and the market efficiency that beneficial ownership transparency (BOT) promises.

When we talk about modelling BO data, we are talking about the process of bringing disparate sources together and structuring the data for our uses. The use case is paramount. You might be reading this as a developer on a transparency project with no major technological constraints but specific, complicated questions about your data. Conversely, you might be implementing a register for a government with a strict specification to satisfy the needs of multiple stakeholders. Hopefully our experiences can help in both, and many other, situations.

In any modelling task there are three key questions to consider:

- What are my objects of interest? In other words, what is it that I am representing with data?

- How should these be stored? The answer to this is often driven by practical considerations as much as theoretical ones.

- How should these be exchanged between systems? This question is particularly significant when such systems were designed around different legal frameworks or business processes.

Question 1 always comes first, but depending on the kind of system being built, a user might have to answer question 2 or 3 next. If building a national register of beneficial ownership, one might be concerned first with collecting data from users, then with how it gets published. If, like us, users are building a system that aggregates data, they might first think about the ideal ways for data to be exchanged. In fact, this is what led us to create the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard.

The Beneficial Ownership Data Standard

Our primary work on modelling data is the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS). This lays out a data model that is designed to be flexible to different legal definitions of beneficial ownership. It also allows changes to ownership to be tracked over time and, crucially, lets users evaluate conflicting claims about ownership alongside each other. BODS does this through primary units of data called statements, which are sub-categorised into statements about entities, persons or ownership. BODS data produces an immutable chain of claims of ownership – ideal for wrangling the complicated, changing nature of ownership – but it is important to highlight that the notion of a ‘claim’ is central. Much beneficial ownership data is just that: claims made by people or companies at particular points in time, and does not always reflect the full truth about ownership.

In our experience, the statement model does not map directly to how many systems model their own data. The core of BODS, however, has a clear set of fields for describing the three pieces of data needed: persons, entities and ownerships. The deep thinking that has gone into those can be a benefit regardless of the conceptual model used.

The key objects of interest according to BODS are shown in the following tables. This is just a summary of the core fields; see the data standard documentation for the full specification.

| Field | Notes |

|---|---|

| Names | People can have multiple names, or versions of their name |

| Identifiers | Similarly, allow for multiple identifiers and clearly denote which system they came from |

| Nationalities / place of birth | Again, nationalities should be multiple |

| Birth date / death date | Allow for uncertainty in dates, e.g. with just a month or year. |

| Place of Residence / tax residencies | Use standards like ISO codes for countries |

| Addresses | We opt for a single string, with separate postal/zip codes and country fields |

| Field | Notes |

|---|---|

| Names | |

| Jurisdiction | Can be a country or a lower level administration |

| Identifiers | |

| Addresses |

| Field | Notes |

|---|---|

| Subject | What is owned or controlled? |

| Interested party | Who, or what, has ownership or control? |

| Interests | An ownership or control relationship can contain many different interests |

| Type | E.g. shareholding, board membership |

| Start date / End date | Can be uncertain again |

| Share percentage | Whenever something can be quantified in percentage terms |

| Is it direct or indirect? | Important to know if we are getting the full picture, or just the ultimate owner |

Conceptual models

BODS’ statement-based model is just that: a model. There are other ways of thinking about BO data which are also useful, and we tend to categorise them all as ‘snapshot-based’. By this, we mean that they capture a particular state of ownership at a particular time, rather than all possible states across the whole of time.

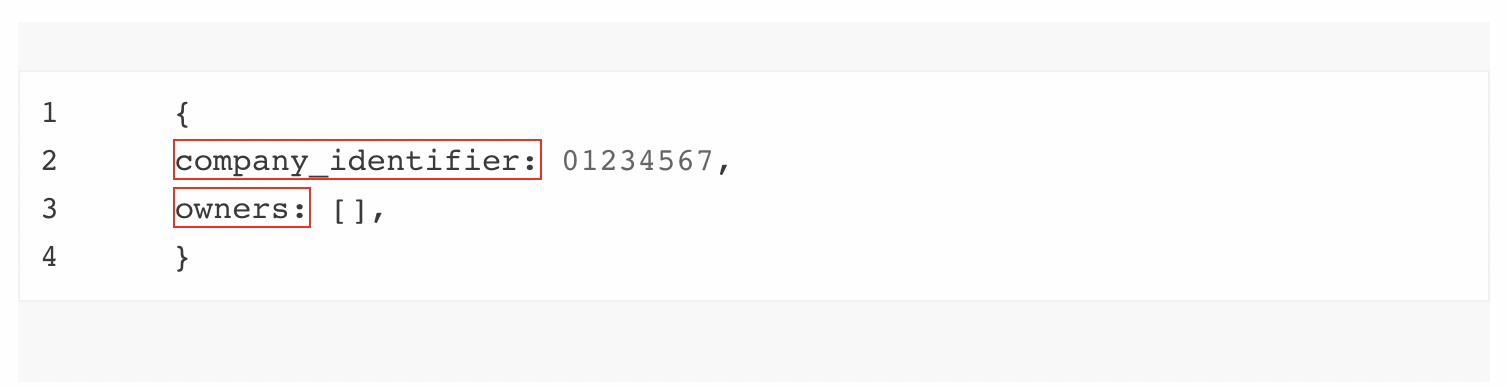

Systems using this model tend to offer company-centric or person-centric snapshots. For example, the UK PSC register is a company-centric register. At a very high level, its data looks like:

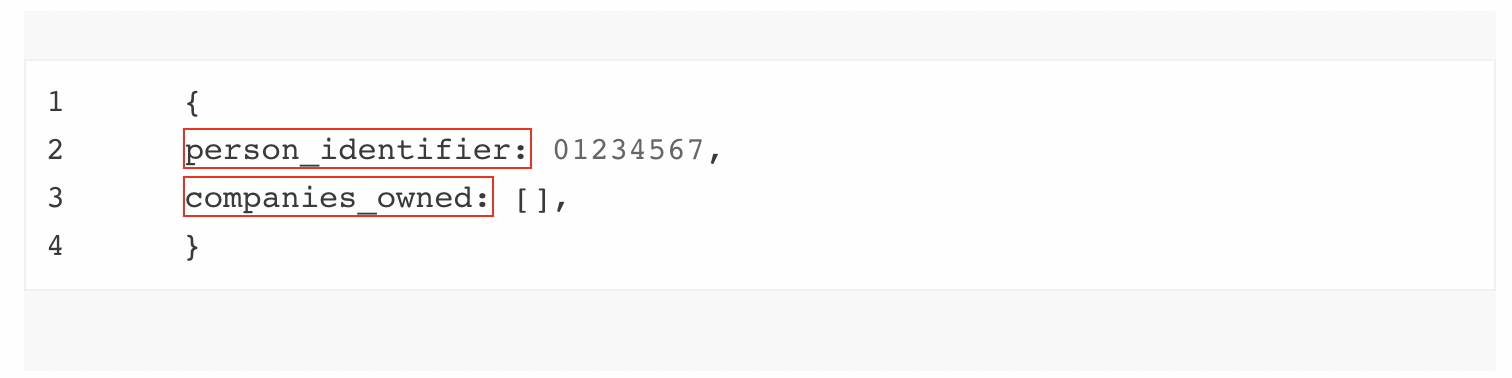

Conversely, Denmark’s Central Business Register offers a person-centric register, and its data is inverted compared to the UK:

There is no intrinsic difference between these two, and underneath different conceptual models the data in individual records is largely the same. However, the choice of conceptual model has significant implications for use of the data. Ultimately, the decision for what model must be guided by the users’ needs and the intricacies of policy.

Company-centric data is most common, reflecting the requirements in most legislation for companies to report their beneficial owners and the fact that strong, unique identifiers for people are rarer. Person-centric data requires a way to reliably and categorically identify individual people, either to authenticate data that people are required to submit, or to link disclosures across different company submissions.

Statement-based models are most useful for publishing data from primary collectors of it – national registers, for example – or for re-publishing data. They allow one to express the provenance and publisher’s confidence in the data more directly. They are also better suited to publish and link data over long periods of time. They introduce overheads that might not be suitable for systems analysing data for shorter time periods or where all of the data is from a single source and therefore all the uncertainty is the same.

In contrast, a snapshot model puts the onus on the user to collect and compare snapshots in order to identify changing data. This in turn puts further reliance on good mechanisms for identification of people and companies, so that they are linkable across snapshots. The advantage of snapshot models is that they correspond to what many users want from BO data most directly – an obvious exposition of the current state of relationships between people and companies.

Storing, querying and exchanging data

Whatever conceptual model is chosen, computer systems will need to be involved in order to store data and provide different users access to it. The most common (and often complimentary) ways to do that are with databases and files.

BODS specifies JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) files as the primary way to transfer data because of its almost universal native support in programming languages, and thus the ease of interchange between different systems. BO data, by its interconnected nature, is better suited to a format that allows nested objects, but there is no fundamental reason it cannot also be transmitted in a tabular way, e.g. CSV files. There is open source tooling to convert nested JSON to flat CSV files, which is compatible with BODS, but use of this often implies some significant constraints from outside factors.

However, file formats are mostly a concern at the edges of systems. Inside their system, users are probably going to want to put their data into some kind of database. Beneficial ownership is inherently a kind of network, so a graph database is in some ways the perfect solution, but the needs of integration, legacy systems and specific access patterns also point to other options.

We will discuss the pros and cons we have found with different systems shortly, but regardless of technology choice there are a few fundamental decisions users will need to make. The first is around the scope of the database. Is only the bare minimum of beneficial ownership information being stored, or is deeper information about companies needed, for example?

BO data often only gives sufficient identifiers to find a company in other systems. If data like previous names or industry classification codes is needed, users might need to expand their data model to include them. Likewise, a beneficial owner is often a tightly defined type of person and we advise that the data collected about them is minimised for privacy reasons. A user’s system may need to record more personal information about people internally than is presented elsewhere, or a user might want to link companies to other types of people: directors, company secretaries or politically exposed persons.

The significant risk in these situations is in duplicating data and it then becoming inconsistent with the primary source. We recommend clearly identifying the original ‘owners’ of any piece of data and establish the precedence of different systems. For example, if core BO data has company names, but company data is populated by reconciliation with another system (e.g. through a company number lookup), should a user overwrite the names in the database with those from the other system? What about cases where the other system does not have a name, but the user does? These are real situations we have faced with Open Ownership’s register that have impacted our work.

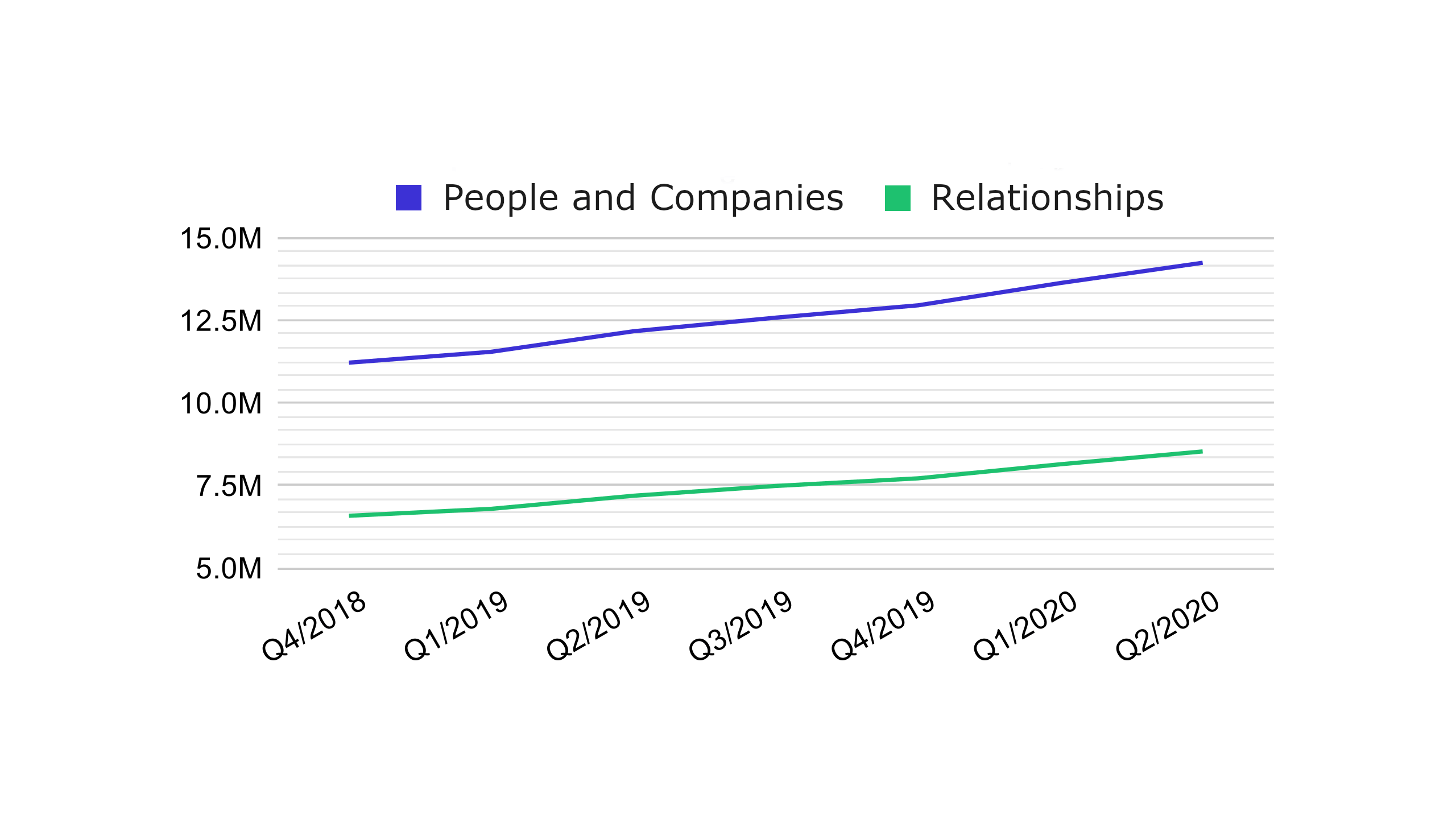

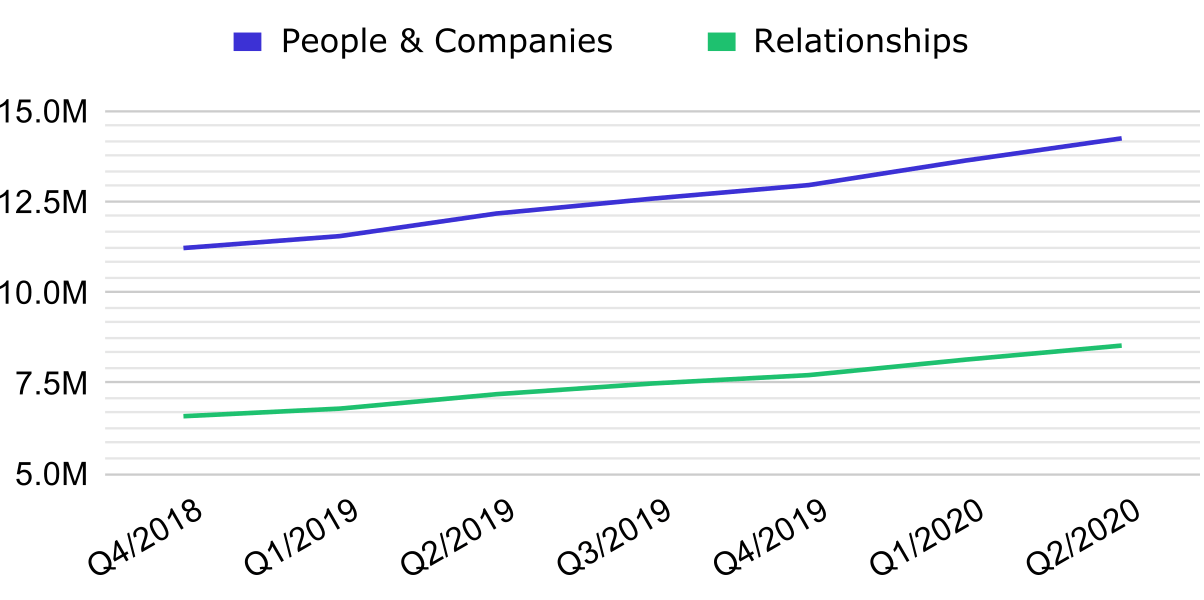

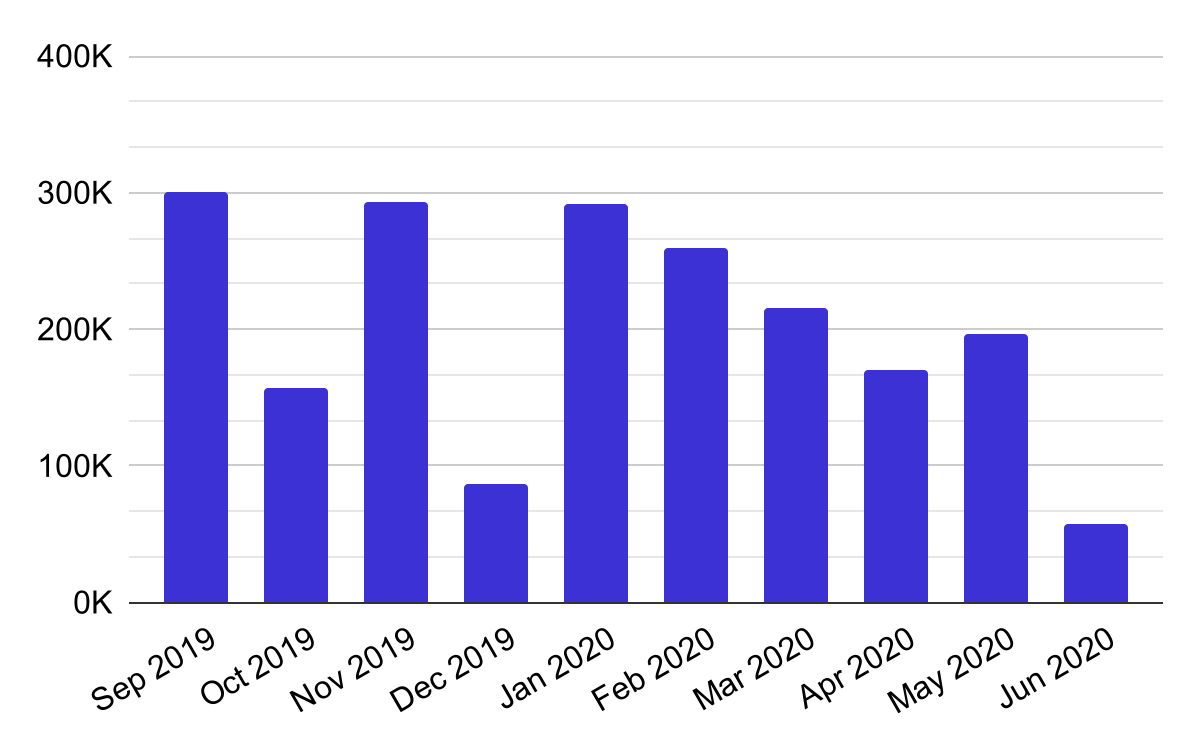

To aid the specification of such systems, it is helpful to have an idea of the size and shape of the data being worked with. The following graphs from our register give some ideas of the core metrics:

Total records, companies, people and ownerships

New or changed records per month

Relational databases

The most common starting point for any system is a relational database. It is a solid choice and can be made to work for almost any use case, but has some specific constraints that are worth being aware of.

The major constraint is around how one traverses relationships between people and companies. It is most common to model people and entities as single rows in one or two tables. Relationships between them are many-to-many, and contain their own interesting properties, so are modelled as another joining table in the most basic case.

The issue comes when querying the database. It is common to ask questions such as ‘who is the ultimate owner of this company?’, or ‘which companies does this person own or control?’ With the model described above, this requires a (potentially expensive) recursive query, or additional procedural code to iterate through relationships until the desired result is achieved. Splitting legal entities and natural persons into two different tables, as would make sense from the norms of entity relationship modelling, complicates this further.

Some amount of de-normalisation can usually help solve this problem – storing direct references to the ultimate owner(s), for example – but relies on knowing the intended query patterns ahead of time and pushes work onto the systems that write into the database.

The above example assumes a snapshot-based conceptual model. A statement-based model is in some ways simpler to model and query, but it will push more responsibility to the querying system if a translation to a snapshot model is required by the user.

Graph databases

Graph databases are designed for exactly the kinds of queries that are problematic for relational databases. Exploring networks, obtaining the nodes along various edges or the leaf nodes of particular graphs is built into their query system. At Open Ownership we don’t have a huge amount of experience with them and have avoided them for our production systems because of this. We have often seen a graph database paired with another database, specifically for the purpose of performing these kinds of queries, which seems to work well. One user has shared their python code for loading BODS data into a Neo4J database – we would love to hear from others who have worked with any vendor’s systems to better understand them.

One particular angle to graph databases that we have tangentially explored is the use of relationships between data to represent analysis. For example, on Open Ownership’s register we dedupe people who have identical details, but we want to make this transparent and reversible, in case it turns out we have made a mistake. Currently, we achieve this through dedicated fields in our database models, tracking whose details have been merged together. A graph database would potentially allow us to describe this merge process through additional edges between person nodes. With that database structure, we would also be able to offer additional query options to users, allowing them to choose their own risk level for false positives.

Other non-relational databases

Open Ownership’s register uses a document-oriented database, MongoDB as its main data store. One drawback we find with this system is its inflexibility when it comes to querying data. Our desire to draw on the register for analysis and evidence for policy making leads us to make many ad-hoc queries. We often find that the only way to perform these is through an expensive (and time-consuming) trawl of all the data – loading the entire dataset into our application framework. The general reliance on the application to perform validation and enforce the notional schema also limits how much we can share access to the database.

We also use Elasticsearch as a search engine for the register, but it can be considered a general-purpose non-relational database as well. We use an API provided by the Danish Central Business register, which is powered by Elasticsearch and its in-built support for HTTP requests. We would be very interested in supporting this approach and learning from any other experiences with it. It has some particular challenges around how to present and index the data stored as ‘documents’ because the mechanisms for representing relationships between documents are not sufficient to model beneficial ownership. For that reason, we see it mainly being an addition to a system, rather than the primary data store.

Exchanging data

This mention of APIs brings us to our final topic: how to exchange data between systems. Because of differing legal systems, business processes and the pragmatic choices made about internal data storage, everyone’s beneficial ownership will look different. However, this is at odds with the need to combine data across jurisdictions to realise the benefits of beneficial ownership transparency, which is why we think it is important to have a shared exchange format.

This is where BODS comes in, as a way to abstract from the specific context and constraints of individual systems. In this context, it is important to give consumers sufficient information to make informed decisions about what data to trust or give precedence to, which is why we opt for the statement-based conceptual model.

Some of the key features of BODS that help with exchanging data are:

- JSON statements for people, entities and relationships that are self-contained, using nested objects and arrays to contain many-to-many relationships within objects

- The use of cross-references between individual statements to reduce duplication when describing relationships between objects

- The use of JSONLINES to support stream processing

- A permissive data schema, which allows additional data to be included and only requires the bare minimum of information but ensures that core data is well-structured

In addition, the metadata fields common to all statements cover the major concerns data users have when re-using other data: provenance, licensing, schema version control and a mechanism for annotating data that has been corrected, transliterated or otherwise transformed.

Summary

We hope that this post has been informative and helps explain some of the key considerations for modelling beneficial ownership data in the real world. We would love to get feedback on whether our explanation of the conceptual models, storage systems and BODS as a system for exchange and long-term data representation are clear, and we would love to hear your own experiences dealing with this kind of data. It is a complex topic that benefits further elaboration, which is why we have decided to write up this series of blogs over the next few months. In coming parts, we will be talking about some of the topics touched on here in more detail, including:

- Reconciling data across systems

- Merging and de-duping records

- Tracking the history of data and its provenance

- Producing BODS from data in other conceptual models

- Analysing data

- Receiving submitted data from users

Related articles and publications

Publication type

Blog post

Topics

Beneficial Ownership Data Standard,

Open Ownership Register

Sections

Technology