Beneficial ownership in Chile's public procurement reform

Progress and steps taken

The Chilean public procurement market

Chile is a high-income country with a population of nearly 20 million. In 2024, the total value of transactions on Mercado Público amounted to USD 16 billion, the equivalent of 5% of the country’s GDP (see Table 1). [6] The platform facilitated the management of procurement activities for over 1,086 purchasing entities and more than 110,000 suppliers, representing a substantial portion of the country’s economically active agents. [7]

The Chilean public procurement market is highly open. [8] This openness, combined with targeted policies supporting MSMEs – such as simplified registration processes, preferential treatment in certain contracting categories, and initiatives for training and financing programmes – has significantly contributed to MSMEs’ ability to compete and access government contracts. [9] As a result, MSMEs have achieved a strong market presence, reaching 40% of the total value procured in 2023.

Table 1. Chilean public procurement market at a glance

|

Value of procurement in 2024 (Source: ChileCompra, Open Data Portal, and Central Bank of Chile. [10]) |

USD 16,542,305,230 (About 5% of the GDP) |

|

Number of tenders in 2024 [11] (Source: ChileCompra, Open Data Portal. [12]) |

1,170,624 |

|

Number of purchase orders in 2024 (Source: ChileCompra, Open Data Portal. [13]) |

2,030,377 |

|

Number of purchasing entities in 2024 (Source: Slide deck provided to Open Ownership by the Observatory of ChileCompra.) |

1,086 |

|

[a] Number of suppliers transacting on Mercado Público in 2024 ([a]=[b]+[c] Source: Interview with executives of ChileCompra (2025)) |

110,000 |

|

[b] Number of suppliers: legal entities and enterprises (Source: Interview with executives of ChileCompra (2025).) |

66,000 |

|

[c] Number of suppliers: natural persons (Source: Interview with executives of ChileCompra (2025).) |

44,000 |

|

MSMEs market share in 2023 (Source: ChileCompra. [14] (2024 data forthcoming)) |

40% |

The legal reform introduced by Law No. 21634

Since its inception in 2003, Public Procurement Law No. 19886 has been amended eight times. [15] Yet, it remained largely unchanged until December 2023, when Law No. 21634 introduced the most significant reform of its history. The reform had multiple aims, including enhancing transparency, strengthening competition, improving efficiency, and upholding integrity in public procurement, while ensuring broader participation of MSMEs.

The reform was designed to be implemented in four phases:

December 2023: Phase 1

- Provisions on conflicts of interest and integrity come into force. All public officials – not just senior executives – are prohibited from selling goods or services to their own agencies. This ban extends to their spouses, close relatives, and any companies in which they hold ownership or beneficial interest. For those involved in procurement, the restriction applies during their tenure and for one year after leaving office.

December 2024: Phase 2

- Registration in the Supplier Registry becomes mandatory for participation in public procurement. Legal entities must disclose their ultimate beneficial owners and administrators. Measures to promote the participation of MSMEs and local suppliers are also implemented.

June 2025: Phase 3

- Innovation and efficiency measures, such as reverse auctions, are introduced.

December 2025: Phase 4

- Public works procurement from the Ministry of Public Works (MOP) and the Ministry of Housing (MINVU) are incorporated into the Supplier Registry.

Legal entities and potential conflicts of interest

Under Chilean legislation, a conflict of interest in public service is defined as a situation in which a public official’s private interest overlaps with the public interest, thereby compromising impartiality. [16] The reformed Public Procurement Law No. 19886 expands the definition of a conflict of interest to include not only senior executives but also all public officers within public institutions. [17] These individuals are prohibited from selling goods and services to the agencies in which they work. This restriction also extends to their spouses or civil partners, relatives, and companies in which they hold membership or beneficial ownership. Similar restrictions apply to employees of non-public organisations that receive public funds exceeding UTM 1,500 monthly (currently equivalent to USD 106,000). [18] For executives and officials involved in procurement processes, the restriction on contracting with their own institution applies both during their tenure and for a period of one year following the end of their service.

Prior to the reform, the national law required legal entities to disclose information on their partners or shareholders in the Supplier Registry. However, these entities were sometimes part of broader and more complex ownership structures, making it difficult – and in some cases impossible – to identify the natural persons who ultimately owned, controlled, or benefited from these structures (i.e. the beneficial owners). The openness of the Chilean public procurement market, with its large number of domestic and foreign participating suppliers, heightened this challenge. Before the reform, registration in the Supplier Registry was not mandatory. This made it significantly more challenging for ChileCompra to identify the individuals behind a wide range of legal entities and effectively prevent misconduct and regulatory breaches, including those related to conflicts of interest. The next sections provide further details on how BOT measures introduced by the reform helped address this challenge.

To ensure better coverage of the new provisions introduced by the reform, the number of institutions regulated by the Public Procurement Law was expanded. According to ChileCompra, these changes will entail, once fully implemented, a 35% increase in the number of purchasing entities regulated by the law (including the Congress, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the judiciary, and municipal corporations) and a 20% increase in associated suppliers. [19]

To support compliance with these new legal obligations and ensure effective enforcement, the reform also strengthened ChileCompra’s oversight role. It established a legal mandate to promote integrity in public procurement, including the obligation to report potential misconduct to oversight bodies – such as the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the CGR, and the National Economic Prosecutor. This includes any actions that may constitute crimes, breaches of probity, or antitrust violations. ChileCompra’s updated mandate also includes the responsibility to establish agreements with public and private entities to exchange data and strengthen the Supplier Registry.

Embedding beneficial ownership transparency measures into reform strategies

BOT provides information about the ownership and control relationships between individuals and legal entities and arrangements, offering a more comprehensive view of a business. This information allows procurement authorities to identify potential conflicts of interest that may not be immediately apparent by revealing any connections between public officials and legal entities involved in bidding processes. [20]

In addition to aiding risk detection, BOT measures have a preventive effect by signalling political action against secrecy. This is especially true when these measures are coupled with public oversight; effective, proportionate, and dissuasive sanctions for noncompliance; and clear pathways for addressing misconduct.

The reform introduced by Law No. 19886 in Chile included BOT requirements to prevent conflicts of interest, illicit financial activities, and anti-competitive behaviour by making ownership structures more visible to procurement authorities and oversight bodies. As of 12 December 2024, all suppliers – whether domestic or foreign, individuals or legal entities – must register in the Supplier Registry to access business opportunities on Mercado Público. Domestic and foreign legal entities are required to disclose their ultimate beneficial owners and administrators as part of the registration process.

According to the Law, individuals are considered beneficial owners when they are natural

persons, whether Chilean or foreign and with or without domicile in Chile, who: (a) hold a share equal to or greater than 10% of the capital, profit rights, or voting rights in a legal entity, investment fund, or unincorporated entity; (b) are able to appoint or cause the appointment, directly or indirectly, of the majority of the directors or administrators of such legal entities, investment funds, or permanent establishments; or (c) exercise effective control over such legal entities, investment funds, or permanent establishments, enabling them to make or influence decisions concerning these entities. [21] If it is not possible to identify the beneficial owner, the law indicates that the term shall be understood to refer to the natural person who directly or indirectly performs management or administrative functions within the entity required to report. [22]

Fostering compliance through business incentives and user-friendly systems

To ensure the effective implementation of BO identification, several key elements were considered, but the use of incentives for suppliers was seen to be the most critical. The key concept used in this context is the eligibility to operate on Mercado Público. Legal entities that fail to submit their BO information are not deemed eligible in the Supplier Registry and cannot participate in the public procurement market. Specifically, the system requires suppliers to provide their BO information whenever they attempt to transact – that is, to submit a bid, send a quotation, or accept a purchase order. In this way, the disclosure requirement is directly linked to a key business process for suppliers, significantly increasing compliance.

The process is as follows:

- For suppliers already registered in the system: Thousands of mass emails are sent to legal entities already registered in the Supplier Registry, encouraging them to declare their BO information and warning that failure to do so may result in removal from the Registry. However, according to ChileCompra officials, the most effective strategy has been linking the disclosure requirement to specific business processes. In practice, when a supplier identifies an attractive business opportunity, intends to submit a quotation, or receives a purchase order, the only way to proceed is by submitting the required information on their beneficial owners.

- For new suppliers: All new suppliers – whether domestic or foreign, and natural persons or legal entities – are required to register in the Supplier Registry. Legal entities must disclose their ultimate beneficial owners, along with the administrators or individuals empowered to make contractual decisions on behalf of the company.

In addition, the BO registration process was designed to place the least possible burden on the individuals disclosing BO information (that is, the system users). Drawing on data from the SII, the Supplier Registry presents system users with a pre-filled declaration form. This form contains all the information already available from the SII, including information on names and ownership percentages of shareholders, along with the legal entity’s tax representative and tax identification number (RUT). [23] Users are only required to provide additional details regarding the legal entity’s beneficial owners when needed. This approach not only streamlines the registration process but also benefits data users by providing more complete and accurate data they can trust, leading to more reliable analysis and informed decision-making in the procurement process.

Tackling implementation challenges

The implementation of the reform has not been without its challenges:

- Over 700 suppliers have required one-on-one support to complete their registration in the Supplier Registry.

- Many suppliers have noted that the information in the system was outdated. In such cases, ChileCompra directs suppliers to update their records with the SII.

- Many large companies listed on the stock exchange market are not required to report their BO information to the SII, but rather to the Financial Market Commission (Comisión para el Mercado Financiero). As a result, these companies have to follow a different reporting process.

- Some large suppliers, including several foreign ones, initially refused to provide the required information, expecting preferential treatment from the administration. Instead, their access to the public procurement market was firmly closed. While many have since complied, a small number still choose not to submit the information, effectively excluding themselves from public contracting opportunities.

The documentation and understanding of these challenges provides a crucial opportunity for ChileCompra to delve into underlying issues and explore avenues for reform and system improvement.

Emerging findings on the effectiveness of reform implementation

Assessment of compliance rates

As of March 2025, 39,039 out of the 66,000 companies required to report their BO information had successfully registered in the system. Within just three months of the mandate taking effect, this resulted in a 59% compliance rate. This strong early uptake reflects both the effectiveness of ChileCompra’s incentive-based approach and the integration of the disclosure requirement into core business processes. Since disclosure is triggered when a company transacts on Mercado Público, it is expected that the remaining companies will comply in due course as they begin to re-engage with the public procurement system.

These results indicate a promising trajectory toward full compliance, while minimising the administrative burden and reinforcing accountability.

The most important results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Beneficial ownership identification in public procurement: Key figures and coverage

| Mandatory information to be provided as of | 12 December 2024 |

|

Number of beneficial owners registered (as of March 2025) (Source: Interview with executives of ChileCompra) |

>100,000 |

|

Number of companies that submitted their BO information (as of March 2025) (Source: Interview with executives of ChileCompra) |

39,039 |

|

Number of legal entities targeted [24] (Source: Interview with executives of ChileCompra) |

66,000 |

| Legal vehicles covered |

– Public limited companies with capital divided into shares (Sociedades Anónimas – S.A.) – Limited liability companies with a defined number of partners (Sociedades de Responsabilidad Limitada – S.R.L.) – Individual limited liability enterprises owned by a single person (Empresas Individuales de Responsabilidad Limitada – E.I.R.L.) – Stock companies offering flexibility in corporate governance (Sociedades por Acciones – SpA) – State-owned enterprises – Foreign companies – Foundations and non-profit organisations |

| Data on beneficial owners in the public procurement market |

Structured data is now stored in ChileCompra’s database, accessible for the CGR and the National Economic Prosecutor’s Office |

The legal reform enabled the integration of BO data into ChileCompra’s systems, significantly strengthening the detection of conflicts of interest. By requiring legal entities to disclose their ultimate beneficial owners, the system can proactively cross-reference this information with ChileCompra’s database of procurement officials, triggering automated alerts to identify potential conflicts of interest. Additionally, information on each awarded legal entity can be accessed on Mercado Público, either through the award minutes of tenders or the purchase orders associated with other procurement procedures.

The role of beneficial ownership transparency in preventing and detecting conflicts of interest

Observatory of ChileCompra’s system and processes for detecting conflicts of interest

The Observatory of ChileCompra is an internal unit of the national public procurement system tasked with promoting efficiency, integrity, and transparency by detecting potential irregularities in public procurement processes. This is achieved through continuous monitoring of Mercado Público as well as by receiving and managing identity-protected complaints. The Observatory applies both preventive and corrective actions to address and mitigate such irregularities. Established in 2013, its functions were formally recognised with the reform of Law No. 21634, which significantly strengthened its authority and impact.

The Observatory’s main approach is to establish a proactive system for conflict-of-interest warnings, which BO information feeds into. Whenever a potential conflict of interest is automatically detected by the system of the Observatory, a notification is sent to the procurement officer responsible for the process. This allows them to provide a statement or take the necessary steps to properly manage the conflict. If the purchasing entity fails to provide a satisfactory response or resolution within five business days, the case is escalated to an official from the Observatory and forwarded to relevant oversight bodies, such as the CGR, as stipulated by the legal reform.

The Observatory detects conflicts of interest using BO information as part of the following business processes:

- purchase orders issued to a supplier where one of the company’s beneficial owners has an active user account with access to Mercado Público as a buyer within the same procurement entity;

- tenders in which one or more members of the evaluation committee are beneficial owners of a bidding supplier;

- tenders where those responsible for the procurement process, payment, or contract execution are beneficial owners of the awarded supplier.

Information on buyers and those responsible for procurement, payments, or contract execution is automatically recorded in ChileCompra’s database when users start operating on Mercado Público. The specific composition of the tender evaluation committee must also be recorded in a structured format for each process in the information system.

One of the most innovative aspects of ChileCompra’s approach has been its decision to publicly disclose the findings of its monitoring efforts through the ChileCompra Observatory – even when irregularities have involved other agencies within the same executive branch. [25] This bold move showcases ChileCompra’s institutional maturity. ChileCompra’s Director, Verónica Valle, underscored this commitment by establishing a groundbreaking performance indicator within her management agreement, that is, the number of conflict-of-interest cases detected through the Observatory’s automated alert system which are subsequently analysed and verified.

Outreach campaigns and capacity-building by ChileCompra

Ahead of the procurement reform, ChileCompra launched the Stop Corruption campaign in October 2023. Its aim was to build early awareness among buyers and suppliers using a dynamic mix of outreach tools, including news features, social media animations, mass emails, and educational infographics on whistleblower protections and direct contracting.

Following the campaign, interest among both buyers and suppliers in the reforms skyrocketed, leading to an unprecedented engagement in outreach activities. This surge in attention translated into recordbreaking attendance at online training sessions and webinars, as public officials sought to better understand the new rules and their implications. [26]

New online courses were delivered via ChileCompra’s training channel for buyers and suppliers to address the changes introduced by the reform – particularly the expanded scope to identify and reduce conflicts of interest. [27] This shift likely represents the most significant cultural change from the reform for both buyers and suppliers, especially for public officials not traditionally involved in procurement roles.

Indicators of a reduction in reported conflict-of-interest cases

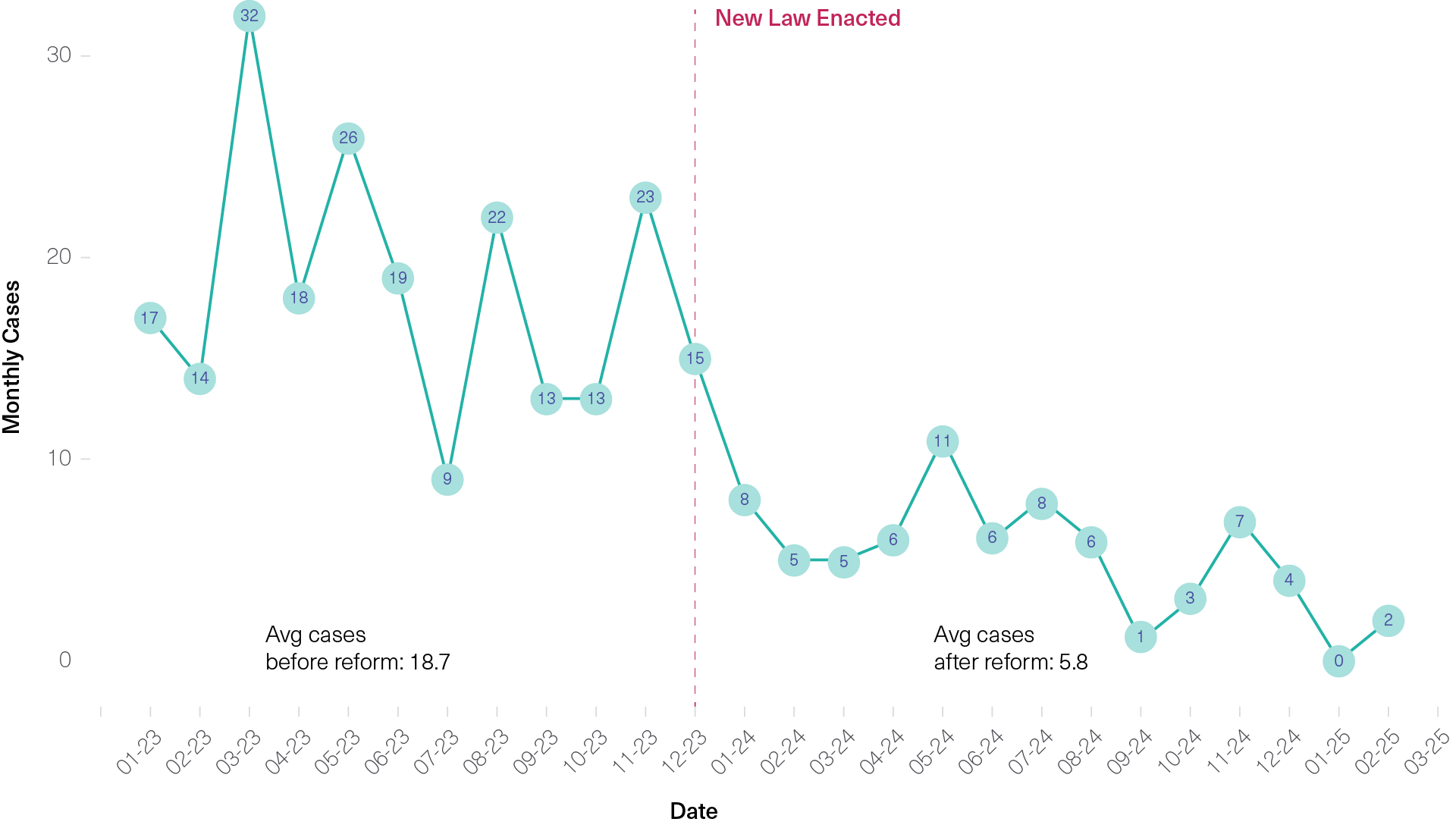

In February 2025, the number of monthly conflict-of-interest cases detected by the preventive monitoring system of the Observatory of ChileCompra had decreased by 69% since the implementation of the law. Prior to the reform, the system recorded an average of 18.7 conflict-of-interest cases per month. After the reform, this average dropped significantly to 5.8 cases per month.

The following chart presents the historical trend in detected cases from December 2022 to February 2025.

Figure 1. Monthly detected cases of conflicts-of-interest before and after public procurement reform

Source: The Observatory of ChileCompra. [28]

This sharp decline could suggest a substantial improvement in the system’s ability to detect and reduce conflicts-of-interest, likely influenced by a combination of stricter regulations, increased transparency, and higher compliance awareness among public officials and suppliers. While isolating the exact impacts of the BOT reforms is challenging due to multiple influencing factors, it can be reasonably assumed that the reforms have played a role in this positive trend.

However, the reduction in detected conflicts may not solely reflect improvements in procurement integrity. Some individuals involved in corrupt practices may have shifted their activities elsewhere, highlighting broader governance challenges. While this indicates the reforms’ success in cleaning up procurement, it also underscores the need for continued efforts to address corruption across other sectors.

The sustained reduction of detected conflicts of interest over the past few years suggests that the implemented preventive system has been not only effective, but also consistently stable in delivering measurable indicators of impact on the prevalence of conflicts of interest in public procurement in Chile. However, the automated system may not be as effective in detecting subtler or more complex conflicts, suggesting room for improvement in its design.

Another valuable tool for identifying conflicts of interest has been the protected-identity whistleblower hotline – an innovation introduced by the recent reform of the Public Procurement Law. Through this confidential channel, the Observatory of ChileCompra has received 208 reports of conflicts of interest, helping to strengthen oversight and reinforce a culture of accountability throughout the system. [29]

Key challenges related to geographical coverage and the scale of policy implementation

While the success of the Observatory of ChileCompra is evident, it represents only a partial view of the broader challenges the system must address. The current figures are based on data from approximately 38,000 public officials directly involved in procurement processes. [30] As data-exchange mechanisms in the CGR, the Civil and Supplier Registries are fully implemented, the scope of monitoring will expand significantly. [31]

However, these stringent measures pose serious challenges in sparsely populated and remote areas, such as Easter Island (municipality of Rapa Nui). Located 3,500 kilometers from the mainland, this overseas municipality has fewer than 8,000 inhabitants, where family ties between public servants and suppliers are common. In such cases, if conflicts of interest are deemed unavoidable, the approval of the contracts must be formalised through a substantiated administrative resolution. This resolution shall then be communicated to the hierarchical superior of the signatory; the CGR; and, in the case of State Administration bodies, the Chamber of Deputies (Cámara de Diputados).

Footnotes

[6] “The World by Income and Region”, World Bank, updated 2025, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html.

[7] According to the SII, the number of active enterprises in 2023 was 722,177. See: “Personas Jurídicas y Empresas”, SII, updated February 2025, https://www.sii.cl/sobre_el_sii/nominapersonasjuridicas.html.

[8] Chile has incorporated public procurement chapters in its free trade agreements, which open up opportunities for foreign suppliers to participate in Chilean public procurement processes. These agreements ensure that international suppliers from signatory countries can compete on equal footing with local suppliers.

[9] “Including SMEs and women in public procurement in Chile”, International Trade Centre, 22 December 2016, https://www.intracen.org/news-and-events/news/including-smes-and-women-in-public-procurement-in-chile.

[10] ChileCompra, “Datos Abiertos de las compras públicas de Chile”; Banco Central Chile, “Cuentas Nacionales – Base de Datos Estadísticos (BDE)”.

[11] This number includes several transactions (procedures for bidding and/or submitting a quote), whether open or restricted, that constitute a business opportunity for a supplier.

[12] ChileCompra, “Datos Abiertos de las compras públicas de Chile”.

[13] ChileCompra, “Datos Abiertos de las compras públicas de Chile”.

[14] “ChileCompra participa de la semana internacional de compras públicas organizada por la OECD”, ChileCompra, 25 October 2024, https://www.chilecompra.cl/2024/10/chilecompra-participa-de-la-semana-internacional-de-compras-publicas-organizada-por-la-oecd/.

[15] “Historia de la Ley N° 21634”, Library of the National Congress of Chile, 11 December 2023, https://www.bcn.cl/historiadelaley/nc/historia-de-la-ley/8245/.

[16] Government of Chile, Law No. 20880, Article 1, “Sobre probidad en la función pública y prevención de los conflictos de intereses”, 5 January 2016, https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1086062.

[17] Government of Chile, Public Procurement Law No. 19886, Article 35, n.d., https://www.suseso.cl/612/w3-propertyvalue-123972.html.

[18] The UTM (Unidad Tributaria Mensual, Monthly Tax Unit) is an inflation-adjusted accounting unit used in Chile to express fines, taxes, fees, legal and procurement thresholds, and other values set by tax or administrative regulations.

[19] ChileCompra, Minuta modernización ley de compras (ChileCompra, 2023), https://www.chilecompra.cl/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Minuta-Modernizacion-Ley-de-Compras.pdf.

[20] Tymon Kiepe and Eva Okunbor, Beneficial ownership data in public procurement (Open Ownership, 2021), 11, https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/beneficial-ownership-data-in-procurement/.

[21] See: Government of Chile, Law No. 19886, Chapter II, Articles 4 and 16; Chapter VII, Article 35; Chapter VIII, Article 43; Chapter IX, Article 53. N.B.: While including critical components of a clear and robust legal definition – such as the notions of both ownership and control, and covering different types of legal vehicles within the disclosure regime – this definition is not fully aligned with commonly accepted international definitions, which suggest that a robust legal definition should state that the beneficial owner must be a natural person. See: Favour Ime and Tymon Kiepe, Guide to drafting effective legislation for beneficial ownership transparency (Open Ownership, 2024), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/guide-to-drafting-effective-legislation-for-beneficial-ownership-transparency/; Open Ownership, “Definition” in Principles for effective beneficial ownership disclosure (Open Ownership, updated 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/principles/definition/.

[22] As elements of the definition of a beneficial owner in the Chilean procurement law could create gaps in effective implementation, ensuring the ChileCompra Observatory monitors and measures these aspects could prove useful to continue assessing the effectiveness of BOT provisions in procurement policy in the future. This could include, for example, monitoring proportions of BO declarations listing legal entities and company representatives as beneficial owners in place of the natural persons ultimately owning, controlling, or benefiting from the legal entities.

[23] Collaboration agreement between ChileCompra and the SII. See: “MATERIA: Aprueba Convenio de Intercambio de Información y Colaboración entre la Dirección de Compras y Contratación Pública y el Servicio de Impuestos Internos”, SII, 5 January 2021, https://www.sii.cl/normativa_legislacion/resoluciones/2021/reso1.pdf.

[24] This is the number of legal entities transacting on Mercado Público over a 12-month period (2024).

[25] For an example of conflicts of interest detected in a service dependent on the executive branch, see: “ORD. Nº.: 0892 – MAT.: Remite Informe N°1432 de 2024, del Observatorio de ChileCompra”, ChileCompra, 19 June 2024, https://www.chilecompra.cl/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/1432_Informe.pdf.

[26] More than 900 participants attended the webinar on conflicts of interest and related topics. See: “Más de 900 usuarios y usuarias de municipios y del sector salud de todo el país participan de webinar que abordó normas de probidad en compras públicas”, ChileCompra, 28 June 2024, https://www.chilecompra.cl/2024/06/mas-de-900-usuarios-y-usuarias-de-municipios-y-del-sector-salud-de-todo-el-pais-participan-de-webinar-que-abordo-normas-de-probidad-en-compras-publicas/.

[27] “Capacitación”, ChileCompra, n.d., https://www.chilecompra.cl/capacitacion/.

[28] Juan Cristóbal Moreno Crossley, “Departamento Observatorio”, ChileCompra, 2024, https://www.chilecompra.cl/organigrama-observatorio/#:~:text=Las%20funciones%20del%20Departamento%20Observatorio,por%20los%20organismos%20del%20Estado.

[29] Cases from 2024 and 2025 (February included). Source: “Denuncias Reservadas”, Observatory of ChileCompra dashboard, ChileCompra, n.d., https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiNDg1ZTMxMzMtZjA0My00MTc3LWJlMWYtMzEwODljYzkxM2U3IiwidCI6ImIwMGQ1ZjQ5LTk4YWMtNGJjNS1hMmM5LWNhZmRmNzEyMTZmMCIsImMiOjR9.

[30] This information is already in ChileCompra’s internal databases.

[31] According to Chile’s Budget Office, the number of permanent public officials in the central government of Chile in 2023 was 636,160, and another 170,743 in municipalities. See: Dirección de Presupuestos, Anuario Estadístico del Empleo Público en el Gobierno Central 2014-2023 (Dirección de Presupuestos, 2024), https://www.dipres.gob.cl/598/articles-336828_doc_pdf.pdf.