Official comment on Beneficial Ownership Information Access and Safeguards, and Use of FinCEN Identifiers for Entities

1. Verification

In order to meet the “core objective of the CTA to establish a comprehensive beneficial ownership database and to ensure that the information it contains is accurate and highly useful,” it is important to holistically consider the range of aspects of implementation that can contribute to improving the accuracy of BOI. In addition to the mechanisms that are often collectively referred to as “verification”, of equal importance are legal requirements to keep information up-to-date, supported by sanctions and their enforcement, and collecting, storing and sharing BOI as well-structured data. The latter will also mean many of the verification checks can be automated, and allow for the use of certain privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs).

OO uses a broad definition of verification: it is the combination of checks and processes that a particular disclosure regime opts for to ensure that the BOI in a central government register is of high quality, meaning it is accurate and complete at a given point in time. OO notes that the definition that FinCEN has used for verification in the notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) is narrower:

“Verification,” as that term is used here, means confirming that the reported BOI submitted to FinCEN is actually associated with a particular individual.

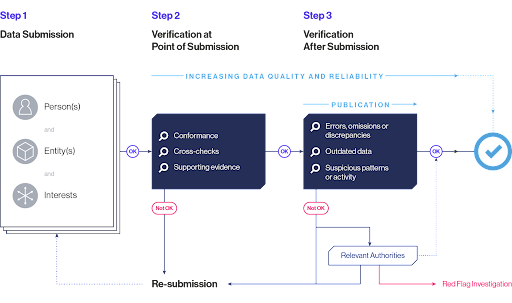

While this is a critical part of verification, narrowly conceiving verification as such risks missing a number of mechanisms that can be implemented to improve data accuracy. These mechanisms should aim to detect and resolve accidental errors as well as deliberate falsehoods. They range from very basic checks which can be built into form design (covered in a subsequent section) to more technologically advanced mechanisms. In OO’s experience, many governments focus on the latter, thereby overlooking low-hanging fruit with respect to improving data accuracy.

While FinCEN may be ultimately responsible for the accuracy of the BOI, FinCEN should not bear the full responsibility for all data verification mechanisms implemented. A whole-of-government approach to verification is most effective, drawing on the full range of resources and information a government holds to check information against.

Broadly, verification mechanisms should cover all the main components of a BO declaration:

- Information about the person: this includes verifying the identity of the beneficial owner or whether the person is who they say they are (as required by the FATF), as well as any information associated with them (for example, contact details).

- Information about the reporting company.

- Information about the ownership or control relationship between them: Generally, this is the most challenging to verify. It is referred to by FATF as someone’s status as a beneficial owner, and its verification is a requirement of the FATF Recommendations.

Governments should also verify information about the individual submitting the information, including their identity and whether they have the authority to do so.

Mechanisms to verify the information at the point of submission should include:

- Ensuring values conform to known and expected patterns: This can be largely automated and built into form design (see following section). For example, checks can ensure that a date of birth is not set in the future. In the Belgian BO register, the system prevents the registration of more than 100% of the shares/voting rights for an individual as this would not technically be possible. These checks are highly effective at preventing accidental errors in the submission of information.

- Ensuring values are real and exist by cross-checking information against existing authoritative systems and other government registers: For example, checks here can include verifying that a ZIP code exists by cross-checking it against a ZIP code database, or checking that the ZIP code associated with the individual in question is in line with other records the government holds. This is done in Latvia, where the registrar verifies addresses by cross-checking them with the State Address register, and in Denmark, where addresses submitted to the Danish Business Register are cross-checked with the Danish Address Register. In Austria, when entities are reporting beneficial owners whose primary residence is in Austria, information is automatically cross-checked with the Central Register of Residents, ensuring that the individuals exist and that their data is accurate.

- Checking supporting evidence against original documents: For example, requiring the submission of shareholder certificates as documentation of ownership held through a certain percentage of shares. In Austria, for non-residents, it is mandatory that a copy of an official photo ID is provided. In the United Kingdom’s (UK) Register of Overseas Entities, [1] verification is required through checking information against “documents and information in either case obtained from a reliable source which is independent of the person whose identity is being verified.” Published guidance provides a list of example sources. In Denmark, foreign addresses are verified by sending a confirmation code by post and requiring this code to be reported back to the registrar.

These approaches are not exclusive and are often implemented together as they can be mutually reinforcing.

After information has been submitted, a designated responsible agency should proactively check it to identify potential errors, inconsistencies, and outdated entries. It should query, remove, and update the data where necessary. The responsible agency should have the legal responsibility, mandate, and powers to do so. Mechanisms should be in place to raise red flags, both by requiring parties dealing with BOI to report discrepancies and by setting up systems to detect suspicious patterns based on experience and evidence. Different countries take different approaches to this. Denmark, for example, manually scrutinises a random sample of higher-risk entries on an annual basis. Many countries, including all European Union member states and the UK, require parties that fall under anti-money laundering (AML) regulations to report discrepancies between the outcomes of their know-your-customer (KYC) and customer due diligence (CDD) checks and information held on the government register.

Austria takes a similar approach as Denmark does, using its National Risk Assessment to assign risk points to a filing based on both the risk of the reporting company being misused for money laundering/terrorist financing purposes and the risk of the report being incorrect. A monthly sample is generated, using a weighting to select more higher risk than lower risk cases. The review also includes ad hoc cases selected by the registrar, which include discrepancy reports received by regulated parties. The sample is then verified manually by using publicly-available data (for example, the Austrian Business Register) and private databases (for example, Bureau van Dijk’s Orbis dataset). [2]

To learn more, please refer to OO’s policy briefing on the Verification of Beneficial Ownership Data.

Example of a business process to improve data accuracy through verification. Source: Open Ownership (2020)

OO notes that the rule contains a series of strict measures concerning the unauthorised sharing and disclosure of BO information with monetary and non-monetary punishments for violation of these. These restrictions need not necessarily restrict the implementation of some of the best-practice verification mechanisms detailed above. There are a range of PETs that are well established and used in the context of AML and KYC/CDD. [3] One example is verification through zero knowledge proofs (ZKPs). ZKPs are a method by which one party can prove to another party that a given statement is true or false, without revealing or exchanging any information except for whether the statement is true or false. As an example, in Ireland, two banks used ZKPs to verify whether the names and addresses submitted by customers during onboarding corresponded to those held by a national utilities company, an authoritative source. The pilot project achieved a 84% success rate in the address verification process taking place between the financial institutions and the authoritative source, and additional measures were identified that would increase the success rate to 96%. The checks, which did not involve sharing the exchange of personal data, were automated and took milliseconds. [4]

Endnotes

[1] The Register of Overseas Entities is a register of the beneficial owners of overseas entities owning UK property.

[2] This case study is based on research Open Ownership conducted as part of the Network of Experts of Beneficial Ownership Transparency (NEBOT). Its findings are expected to be published in 2023.

[3] For more information and examples of PETs in financial intelligence sharing, please see: Future of Financial Intelligence Sharing, “The PET Project - FFIS Research.”

[4] For the detailed case study, please see: Nick Maxwell, “Innovation and discussion paper: Case studies of the use of privacy preserving analysis to tackle financial crime”, Future of Financial Intelligence Sharing (FFIS) research programme, Version 1.3, January 2008.