Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts in South Africa

Background

Beneficial ownership transparency

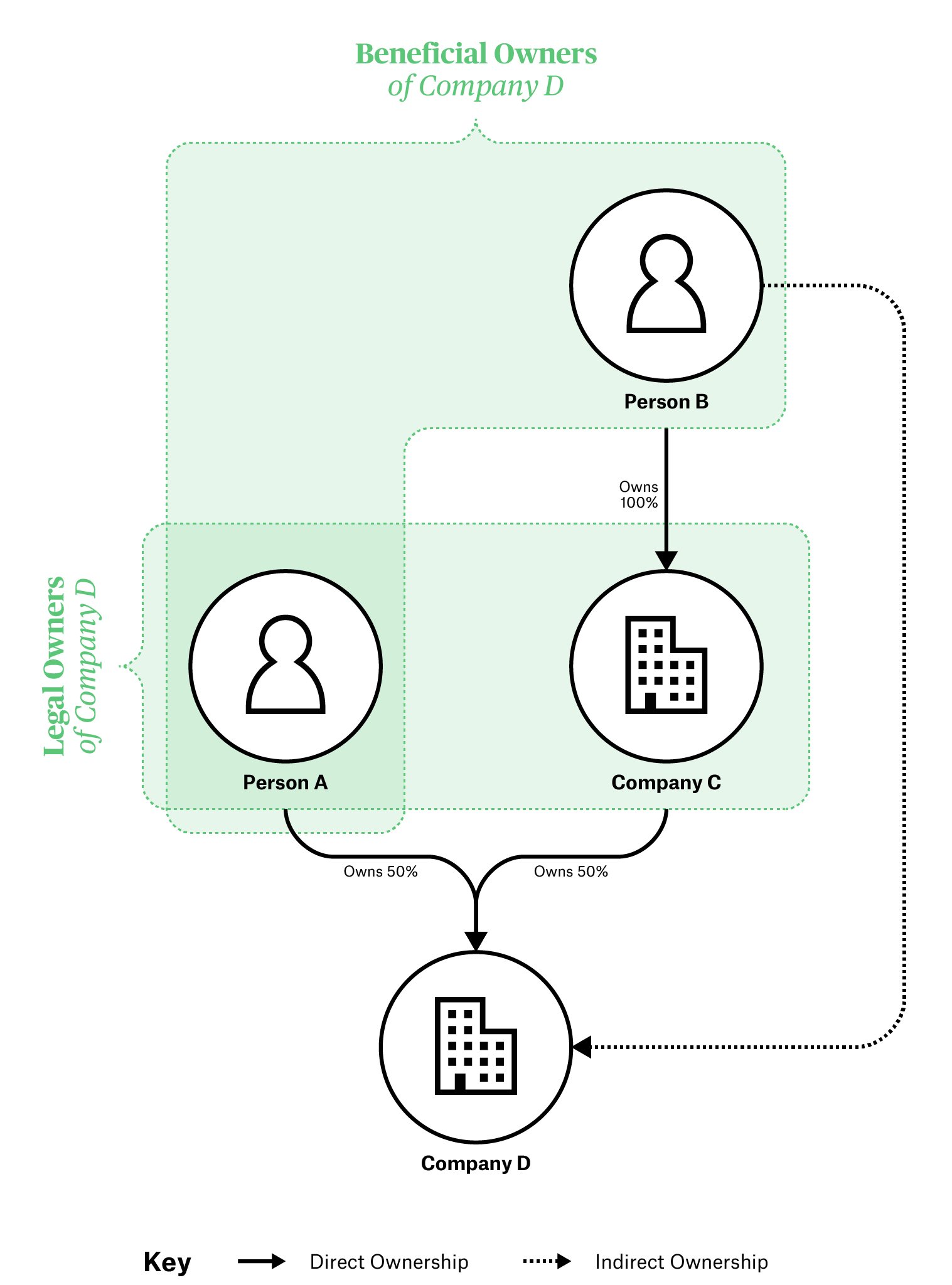

BOT refers to better visibility of the natural person(s) who ultimately own or control assets, legal arrangements, or legal entities. This natural person will often have some form of control over the legal entity (or legal arrangement) or have access to the entity’s assets or income. As companies can own other companies, legal ownership information, or information about the first level of ownership, is often not sufficient to understand the ownership and control of companies. Access to information on beneficial ownership is used by various actors to achieve a range of policy aims:

- State use: BO information is useful for state functions, including for purposes of law enforcement and investigations, and ensuring transparent procurement processes.

- Private sector use: BO information is used by DNFBPs (including legal professionals and company and trust service providers) and non-obliged private sector firms in functions, such as due diligence investigations and risk management.

- General public use: The general public, including civil society and the media, can use BOT information to improve transparency and accountability. In recent years, investigative journalists have used BO information in various high-profile investigations, including the Panama Papers and the Pandora Papers.

Figure 1. Beneficial owners versus legal owners

The BOT of legal entities has recently gained traction with governments across the world as an effective vehicle for combating IFFs, corruption, and tax evasion. [10] Over 120 countries have made commitments to implement reforms of the regimes managing the BOT of legal entities (predominantly companies), but commitments on the BOT of trusts and similar legal arrangements are still trailing behind. [11] International organisations, such as the FATF, the G7, the G20, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the United Nations (UN), and the World Bank, are also in support of BOT reforms, and have committed finances and technical expertise to assist countries with developing and implementing reforms.

BOT reforms require a multifaceted and whole-of-government approach for successful implementation, which includes a robust policy and legislative framework; effective systems and procedures; and data management. For example, countries that implement BOT using a structured data standard for the capture, storage, and sharing of data enable its utility across different use cases. [12]

The OO Principles provide guidance to governments on how to approach adopting such a standard and design policy framework in a way that empowers the establishment of an effective disclosure regime. [13] Whilst the OO Principles were originally designed for the BOT of legal entities, they also provide a useful framework for understanding the BOT of trusts. The OO Principles are interrelated and interdependent, but can be categorised into three broad areas: disclosure and collection; storage and auditability; and quality and reliability. Additionally, the 2015 G20’s High-Level Principles relating to BOT are intended to improve the transparency of legal persons and arrangements, with the aim of protecting the integrity and transparency of the global financial system. [14]

Box 1. The OO Principles [15]

Disclosure and collection

- Definition: Beneficial ownership should be clearly and robustly defined in law. For trusts, any individuals that may exercise ultimate control over the trust should be included.

- Coverage: Disclosure requirements should comprehensively cover all relevant types of entities and arrangements, including different types of trusts.

- Detail: BO declarations should collect sufficient detail to allow users to understand and use the data.

Storage and auditability

- Central register: BO data should be collated in a central register.

- Access: Sufficient information should be accessible to all data users without undue restrictions.

- Structured data: Information should be collected, stored, and shared as structured and interoperable data.

Quality and reliability

- Verification: Measures should be taken to verify the data.

- Up-to-date and historical records: Data should be kept up to date and historical records should be maintained.

- Sanctions and enforcement: Effective, proportionate, dissuasive, and enforceable sanctions should exist for noncompliance with disclosure requirements, and be enforced.

Box 2. The G20 High-Level Principles [16]

The G20 High-Level Principles, as they relate to trusts, are:

- Countries should have a definition of beneficial ownership that captures the natural person who ultimately owns or controls the legal persons/ arrangement.

- Countries must assess existing and emerging risks associated with the different types of legal persons and arrangements, and take appropriate measures to mitigate those risks.

- Legal persons must maintain BO information onshore/locally, and that information should be adequate, accurate, and current.

- Competent authorities should have timely access to adequate, accurate, and current information regarding the beneficial ownership of legal persons.

- Trustees must keep adequate and accurate BO information on the parties to a trust and similar legal arrangements.

- Competent authorities should have timely access to adequate, accurate, and timely information regarding the beneficial ownership of legal arrangements.

- Financial institutions and DNFBPs, including trust service providers, must identify and take reasonable steps to verify the beneficial ownership of their customers. The government should ensure supervision of these obligations and adopt effective, proportionate, and persuasive sanctions for noncompliance.

- National authorities should cooperate effectively domestically and internationally. Competent authorities should participate in information exchange with their international counterparts.

- Countries should support G20 efforts to combat tax evasion by ensuring information is accessible to tax authorities and that it can be exchanged with relevant international counterparts.

Despite ambitious plans and commitments, implementation of BOT reforms remains lacking. Specifically, significant work remains in strengthening disclosure requirements; improving the interoperability of BO information between various agencies; verifying registered information; and engaging citizens in monitoring and accountability. [17]

Implementing BOT reforms can be a complicated policy intervention requiring the cooperation and coordination of multiple governmental departments and non-government stakeholders. Reforming processes and systems will take time, and funding a technical system to implement reforms might be challenging. However, the benefits of such reforms are likely to far outweigh the costs of implementation, including the economic value generated through data reuse, and the reduced loss of tax revenues linked to corruption, money laundering, and tax evasion. [18] This is particularly relevant for South Africa, which has socio-economic inequalities and pervasive levels of poverty, and a reported tax shortfall of ZAR 175.2 billion (approximately USD 11 billion) in the 2020-2021 financial year. [19]

Arguments against BOT include the contention that collecting BO data can be costly and ineffectual if it is not done on a global level because ownership structures often stretch across international borders, meaning, the problem will simply be displaced. Without cooperation and coordination, data remains merely data rather than useful information. Moreover, sceptics argue that broad access to BO information can place individuals at risk of becoming targets of extortion, abduction, and identity theft. [20] The inherent tension between BOT and privacy is clear, and governments have to make a values-driven decision about the trade-offs between protecting privacy and the broader public interest in collecting and publishing BO information.

Differences between legal entities and trusts

Whilst the above discussion provides a useful overview of BOT in general, it is also largely applicable to legal entities. However, there are fundamental differences between legal entities and trusts that have a significant impact on BOT considerations. The principal difference relates to the legal nature of trusts: whilst legal entities have legal personality (and can, thus, own property and conduct transactions), trusts do not. [21]

Rather, trusts are legal arrangements in terms of which a holder of rights (the “founder” or “settlor” in an asset, the “trust assets”, which may include legal entities) can transfer the use and benefits of such rights to another person (the “trustee”, which can be a natural or legal person) who will be responsible for the administration and management of the trust assets. The trustee must manage the trust assets for the use and benefit of another person (the “beneficiary”, which could be a natural or legal person – including trust-like structures, or class of persons) identified by the founder. [22]

Table 1. Principal differences between legal entities and trusts

| Legal entities | Trusts | |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Legal person that exists separately from its shareholders. Rights and responsibilities accrue in the name of the legal entity. | Legal relationship where property is held by trustees and administered on behalf of trust beneficiaries. |

| Creation | Memorandum of incorporation (MOI) or similar registration document, as required by law. | Through a last will (testamentary trust); a contract (in the form of a trust deed); or a court order. |

| Membership | Shareholders can be any person, legal or natural, including other legal entities, individuals, and trusts. | Founders, trustees, and beneficiaries can be natural or legal persons. Trustees will always be represented by a natural person. |

| Control | Board of directors. | Trustees. |

| Owner of assets | The legal entity owns its assets, whilst the shareholders own shares in the company (and are thus entitled to the proceeds from the use of the assets). | The trust is not a separate legal person and, thus, does not own any assets. Assets bequeathed to the trust are legally owned by the trustees, but they have no rights to the assets and must manage it to the benefit of the beneficiaries. |

| Profit distribution | Profits belong to the company, but can be distributed to shareholders through dividends. | Profits accrue either to the beneficiaries or the trust fund itself. |

| Access to information | Public companies must publish audited financial statements and information of directors. Private companies must register an MOI and disclose the identity of directors. | Access to information (other than the identity of the trustees) will only be granted to persons showing material interest, to the discretion of the Master of the High Court. |

Source: Olivier et al., Trust Law and Practice.

International standards

The difference in legal nature between legal entities and trusts means that it is often more challenging to identify the beneficial owners of trusts. The primary challenge lies with the opacity of trusts, as the identities of the parties to a trust are often concealed, in accordance with legal protections to individual privacy. To counter the abuse of these protections, various international bodies have developed guiding principles for the BOT of trusts.

The primary instruments used by international bodies with regards to the BOT of trusts are the FATF Recommendations, the European Union’s fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD5), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Common Reporting Standard (CRS). As South Africa is a member of the FATF and a signatory to the CRS, the primary focus of this discussion will relate to those instruments. Additionally, South Africa is also committed to the G20 High-Level Principles discussed above. However, there are some minor differences in these approaches.23 In many cases, the AMLD5 provides more stringent directives on the BOT of trusts, and reference will be made to the AMLD5 where relevant.

Defining beneficial ownership of trusts

According to the FATF Recommendations, the beneficial owner of a trust is any natural person(s) who benefit(s) from or exercise(s) control over a trust. [24] However, determining who actually exercises control over a trust is challenging, due to the nature of trusts and the roles of the various parties. In recognition of this challenge, the FATF Recommendations, the CRS, and the AMLD5 define all the parties involved in a trust as being beneficial owners. It is important to note that the FATF is currently reviewing Recommendation 25, which deals specifically with the BOT of legal arrangements, and is expected to revise the Recommendation in February 2023. [25]

Applying this approach to the South African context would mean that the founder(s), the trustee(s), the beneficiaries or class of beneficiaries, and any other natural person exercising ultimate control over the trust are viewed as the beneficial owners of a trust. [26] In practice, this means that the beneficial ownership of trusts is approached differently than the beneficial ownership of legal entities: ownership thresholds for determining whether someone qualifies as a beneficial owner of a trust do not apply, and all parties (or classes of parties in the case of beneficiaries) should be identified from the moment the trust is established. [27]

Disclosure requirements

The FATF Recommendations, the AMLD5, the CRS, and the G20 High-Level Principles require that member states take measures to ensure BOT for trusts, which can include establishing disclosure requirements on trustees, financial institutions, and DNFBPs, as well as establishing a central BO register of trusts.

- Requirements for trustees: The FATF Recommendations, the CRS, and the G20 High-Level Principles place an obligation on trustees to obtain and hold adequate, accurate, and current BO information on the beneficial owners of a trust. Trustees must also disclose their status as a trustee when forming a business relationship or carrying out occasional transactions above the prescribed threshold in their capacity as a trustee. [28]

- Requirements for financial institutions and DNFBPs: According to international instruments, financial institutions and DNFBPs are required to take reasonable steps to determine and verify the BO information of trusts during customer due diligence processes.

- Establishing a central register of beneficial ownership of trusts: The AMLD5 is currently the only instrument requiring member states to have a central register of beneficial ownership of trusts. However, the FATF Recommendations have highlighted the establishment of such a register as best practice, and the forthcoming amendments to FATF’s Recommendation 25 about trusts and other legal arrangements may take further steps in this direction. The potential considerations of a central register of the beneficial ownership of trusts in South Africa, including the scope of and access to the register, will be discussed in more detail below.

The international frameworks need to be taken into account by South African policymakers, and have practical implications for considerations relating to reforming South Africa’s BOT of trusts regime.

Global state of the beneficial ownership transparency of trusts

The efforts conducted by global institutions have firmly placed the discussion about BOT reforms on various national agendas. Yet, implementation of BOT reforms remain unsatisfactory. According to the Tax Justice Network’s 2022 Financial Secrecy Index, 68% of the 141 countries surveyed have legislation that requires complete legal ownership disclosure for legal entities. However, in 68% of countries surveyed, recorded company legal ownership is still deemed to be extremely secretive (not necessarily the same 68% of countries mentioned in the previous sentence). In essence, this means that financial secrecy is still facilitated through opaque ownership structures, despite legal requirements of ownership disclosure. [29] The countries surveyed were significantly further behind in terms of facilitating financial secrecy through trusts. [30]

Even in those countries where registration of the BO information of trusts is required by law, the conditions for BOT of trusts are not ideal and typically lag behind the BOT of legal entities. Most significantly, there remain challenges with regards to access to verified, up-to-date, and accurate trust data. [31] For instance, public access to trust information was not yet facilitated in any of the jurisdictions studied by the end of 2019. [32] Denmark provides free access to information on foreign trusts in its business register, whilst Ecuador provides free online access to some information regarding the ownership data of domestic trusts. [33] In South Africa, only the names of the trustees are made available online by the Master’s Office.

Another key element to note is that BO disclosure requirements alone do not guarantee the accuracy of the information, especially where there are no measures requiring frequent verification and where no effective sanctions are in place. [34]

Corruption, IFFs, and tax evasion are global phenomena, and the top 10 highest contributors to financial secrecy are based in the global north. The United States alone supplies 5.74% of the world’s financial secrecy, compared to the top five African countries’ (Algeria, Angola, Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa) combined contribution of 5.22%. [35] Nonetheless, the impact of ownership secrecy is especially relevant in Africa, where the political and economic elite hide behind the veil of secrecy afforded by trusts in order to loot state resources and reduce their tax obligations. [36]

According to the UN Economic Commission for Africa’s High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa, improving transparency, which includes the disclosure of BO information, is critical to countering IFFs in the continent. [37] According to the Panel, all African countries should require disclosure of BO information when registering companies and trusts, or when entering into government contracts.

According to a 2020 Tax Justice Network paper, only the Seychelles and South Africa require that all parties to a domestic law trust be registered, but neither of those two countries make all the BO information available online. Whilst five countries (Angola, Cameroon, Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia) do not allow for the creation of trusts, there are a further nine countries that do not require that the parties to a trust be registered, according to the paper. [38] Although it was not surveyed in the paper, Namibia also requires that all parties to a domestic law trust be registered.

South Africa’s challenges with BOT of trusts are, thus, not unique in the context of international developments. The vast majority of jurisdictions worldwide are still in the process of establishing effective BOT of trusts regimes. However, as the contextual analysis below will indicate, there is a compelling case for action in South Africa, and the country can act as an example for other jurisdictions.

Endnotes

[10] “Open Government Partnership Global Report: Democracy beyond the ballot box”, Open Government Partnership, Volume I, 19, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Global-Report_Volume-1.pdf.

[11] For a full list of countries that have made commitments, please see: “The Open Ownership map: Worldwide commitments and action”, Open Ownership, n.d., https://www.openownership.org/en/map/.

[12] Tymon Kiepe and Jack Lord, “Structured and interoperable beneficial ownership data”, Open Ownership, 12 August 2022, https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/structured-and-interoperable-beneficial-ownership-data/.

[13] “Open Ownership Principles for effective beneficial ownership disclosure”, Open Ownership.

[14] South Africa endorsed the G20 High-Level Principles in 2015. South Africa’s lack of compliance with these principles has contributed to the introduction of the Companies Amendment Bill in 2021, which proposes significant amendments to the Companies Act of 2008.

[15] “Open Ownership Principles for effective beneficial ownership disclosure”, Open Ownership.

[16] “G20 High-Level Principles on Beneficial Ownership Transparency”, G20, 31 August 2015, https://star.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/g20_high-level_principles_beneficial_ownership_transparency.pdf.

[17] “Open Government Partnership Global Report: Democracy beyond the ballot box”, Open Government Partnership.

[18] “Open Government Partnership Global Report: Democracy beyond the ballot box”, Open Government Partnership.

[19] Siphelele Dludla, “Tax shortfall improves after better collections in second half of last year”, IOL, 6 April 2021, https://www.iol.co.za/business-report/companies/tax-shortfall-improves-after-better-collections-in-second-half-of-last-year-4cffbddc-be66-46d5-aa3d-f0ec3a16b8e2.

[20] S. Alexandra Bieler, “Peeking into the house of cards: Money laundering, luxury real estate and the necessity of data verification for the Corporate Transparency Act’s beneficial ownership registry”, Fordham Journal of Corporate and Financial Law, 27, no. 1 (2022): 193-234, https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1506&context=jcfl.

[21] For a more detailed discussion on trusts in South Africa, please refer to: Krige and Wolmarans, An introduction to trusts in South Africa: A beneficial ownership perspective. Additionally, this Open Ownership policy briefing provides detailed information on the international perspective on the BOT of trusts: Ramandeep Kaur Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts, Open Ownership, 1 July 2021, https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/beneficial-ownership-transparency-of-trusts/.

[22] Olivier et al., Trust Law and Practice.

[23] For more information on these differences, please see: Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[24] FATF Guidance: Transparency and Beneficial Ownership, (Paris: FATF, 2014), https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/guidance-transparency-beneficial-ownership.pdf.

[25] “Revision of Recommendation 25 - White Paper for Public Consultation”, FATF, 2022, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/fatfrecommendations/documents/r25-public-consultation.html; “Revision of R25 and its Interpretive Note – Public Consultation”, FATF, 2022, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/fatfrecommendations/documents/r25-public-consultation-oct22.html.

[26] In many international frameworks, including the FATF Recommendations, mention is made of protectors. Protectors are appointed by the founder of a trust to “protect” the interest of the trust and provide oversight to the administration of the trust completed by the trustees. Protectors are not recognised in South African law, and mention is thus not made of protectors when discussing relevant issues.

[27] Chhina, Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

[28] The AMLD5 requires more comprehensive disclosure from trustees than the current FATF Recommendations or the CRS: BO information must be held if a trustee is resident in a member-state even if the trust is registered in another jurisdiction. Additionally, trustees must disclose their trustee status and information on the beneficial owners when conducting occasional transactions above the threshold.

[29] For more information on the methodology and specific results, see: “Financial Secrecy Index”, Tax Justice Network, 2022, https://fsi.taxjustice.net/.

[30] “Financial Secrecy Index”, Tax Justice Network.

[31] “Financial Secrecy Index”, Tax Justice Network.

[32] “Financial Secrecy Index”, Tax Justice Network.

[33] “Financial Secrecy Index”, Tax Justice Network; For details, see: Andres Knobel and Florencia Lorenzo, “Trust Registration around the World”, Tax Justice Network, July 2022, 26-27, https://taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Trusts-FATF-R-25-1.pdf.

[34] “Financial Secrecy Index”, Tax Justice Network.

[35] “Financial Secrecy Index”, Tax Justice Network.

[36] Rachel Etter-Phoya, Eva Danzi, and Riva Jalipa, Beneficial ownership transparency in Africa: The state of play in 2020, Tax Justice Network and Tax Justice Network Africa, June 2020, https://taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/2020-Beneficial-Ownership-Transparency-in-Africa.pdf.

[37] Illicit financial flows: report of the High Level Panel on illicit financial flows from Africa, (Addis Ababa: United Nations. Economic Commission for Africa, 2015), https://repository.uneca.org/bitstream/handle/10855/22695/b11524868.pdf.

[38] Etter-Phoya et al., Beneficial ownership transparency in Africa: The state of play in 2020.

Next page: Beneficial ownership transparency and trusts in South Africa