Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts

Beneficial ownership disclosure and transparency of trusts

International policy and regulatory frameworks

The BOT of trusts has become a major policy and regulatory concern for international AML/CFT standard-setting bodies. The EU (AMLD5), the FATF (Recommendation 10), and the OECD (Common Reporting Standard) have developed the three main international instruments dealing with BO of trusts. This section analyses these policy frameworks at the international level.

Defining the beneficial ownership of trusts

The FATF defines a beneficial owner as “the natural person(s), at the end of the chain, who ultimately owns or controls the legal arrangement, including those persons who exercise ultimate effective control over the arrangement, and/or the natural person on whose behalf a transaction is being conducted”.[7] In other words, the beneficial owner is the natural person or persons who benefit from or exercise control over a trust. Considering different types of trusts, the different parties that are involved in a trust relationship and the fact that the documents that contain this information are private, it sometimes becomes difficult to identify which party benefits from or exercises control over a trust. For instance, in a discretionary trust, a trustee is expected to have discretion on deciding when, how, and to whom the trustee would distribute the trust assets. However, there is a possibility that a settlor might still be retaining control over a trustee (or the trust) through a letter of wishes, by appointing a protector, or by giving power of attorney to a close associate to either veto or remove the trustee.

To mitigate the complexity in identifying the beneficial owners of trusts, the FATF and the AMLD5 have defined all of the parties involved in a trust as the trust’s beneficial owners. The following roles need to be identified and verified:

- settlor(s);

- trustee(s);

- protector(s) (if any);

- beneficiaries or class of beneficiaries; and

- any other natural person exercising ultimate effective control over the trust.[c]

For other legal arrangements similar to trusts – such as fiducia, certain types of treuhand, fideicommissum, private foundations, or waqf, where such arrangements have a structure or functions similar to trusts – parties in equivalent or similar positions, as for trusts above, are required to be identified and verified.[8]

Unlike the definition of beneficial owners of legal persons, as provided by FATF Recommendations, there is no cascading test[d] applicable to identifying the BO of trusts; all the parties to a trust have to be identified from the beginning when establishing a business relationship. Thresholds commonly feature in definitions of BO of legal persons – e.g. 25% or more voting rights or shares for companies. However, because of the nature of trusts and the difficulty in establishing who exercises ultimate control, or who ultimately benefits from the arrangement, no thresholds apply to trusts. To ensure no beneficial owners are left undeclared, the common approach taken is to consider all parties to a trust as beneficial owners. The FATF and the AMLD5 require that all parties to a trust should be identified and verified from the beginning, regardless of the proof of control.[9] For instance, settlor(s) should be identified whether it is a revocable or irrevocable trust.[e] Similarly, all beneficiaries or each class of beneficiaries should be identified even if it is a discretionary trust[f] or a trust in which a particular beneficiary only holds a beneficial interest of 1% in the trust property.[10]

The OECD’s Common Reporting Standard (CRS) for automatic exchange of financial account information is currently implemented by more than 100 jurisdictions (including all EU member states); its definition of beneficial owners of trusts does not differ drastically from the AMLD5 and the FATF definitions, except that the CRS uses the term “controlling persons” instead of “beneficial owners”.[g] The CRS clearly states that the term “controlling persons […] must be interpreted in a manner consistent with the FATF”.[11]

Despite the apparent uniformity in the definitions of beneficial owners of trusts, as indicated in the table below, there are several minor differences that have the potential to create some uncertainty in their application at a practical level. For instance, if there is more than one settlor or protector for a trust, a trustee can, under the FATF definition, simply register only one settlor or protector instead of all settlors or protectors.[h] Thus, the definition of beneficial owners of trusts or similar legal arrangements should be made uniform at the international level.

| Definition of beneficial ownership | FATF (Interpretative Note to Rec. 10) | EU AMLD5 (Art. 31) | OECD/CRS (Section VIII, subparagraph D6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trusts | the settlor | the settlor(s) | the settlor(s) |

| the trustee(s) | the trustee(s) | the trustee(s) | |

| the protector (if any) |

the protector(s) (if any) |

the protector(s) (if any) |

|

| the beneficiaries or class of beneficiaries | the beneficiaries or class of beneficiaries |

the beneficiar(ies) or class(es) of beneficiaries |

|

|

any other natural person exercising ultimate effective control over the trust (including through a chain of control/ownership) |

any other natural person exercising ultimate effective control over the trust |

any other natural person exercising ultimate effective control over the trust |

|

| Other types of legal arrangements |

persons in equivalent or similar positions |

persons in equivalent positions in similar legal arrangements |

persons in equivalent or similar positions |

Disclosure requirements

Both the FATF Recommendations and the AMLD5 require countries to take certain measures to ensure the BOT of trusts. However, there are differences in the approaches taken by the two frameworks. The FATF Recommendations are more relevant for obliged entities that are subject to AML/CFT regulations, whereas the AMLD5 requirements extend beyond obliged entities, requiring the member countries to establish a central register of the BO of trusts. This section discusses the requirements of the BOT of trusts by analysing three key aspects covered in these frameworks: a) disclosure requirements imposed on trustees; b) requirements for financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs); and c) the requirement to establish a central BO register of trusts.

Requirements for trustees

Both the FATF and the AMLD5 impose requirements on trustees to obtain and hold adequate, accurate, and current BO information regarding the trust. Nonetheless, there is a major difference in the approach taken, as highlighted in Table 2 below.

| FATF | AMLD5 |

|---|---|

|

Trustees of any express trust governed under their law to obtain and hold adequate, accurate, and current BO information regarding the trust |

Trustees of any express trust administered in the member state shall obtain and hold adequate, accurate, and current BO information regarding the trust[1] |

|

Trustees required to disclose their status as a trustee to financial institutions and DNFBPs, when as a trustee, forming a business relationship or carrying out occasional transactions above the prescribed threshold |

Trustees or persons holding equivalent positions in similar legal arrangements shall disclose their status and provide the relevant information on beneficial owners to obliged entities in a timely manner, where, as a trustee or as a person holding equivalent position in similar legal arrangements, they form a business relationship or carry out occasional transactions above the prescribed threshold |

To give an example, under the FATF standards, if a trust is governed by the law of Country A, Country A will require trustees to obtain and maintain the BO information on the trust. However, if a trust is governed by the law of Country B but its trustee is a resident in Country A, the trustee is not required under Country A’s laws to obtain and maintain the BO information of the trust, notwithstanding such a requirement on the trustee by the law of Country B. Such a scenario would result in a problem for Country B, as it would be difficult for Country B to practically enforce its disclosure requirement on a trustee that is resident in Country A. To deal with this issue, the approach taken by the AMLD5 appears to be better, in that it requires EU member states to impose a requirement to obtain and hold BO information on all trustees if a trust is administered in their respective jurisdiction. Now, if Country B authorities need to obtain this information, it might be available in a timely manner under the AMLD5 (if Country A is an EU member state).

Box 1: Provisions requiring trustees to obtain and hold beneficial ownership information relevant for non-trust law countries[j]

Under the AMLD5, trustee requirements are applicable to all EU member states – whether a trust law country[k] or non-trust law country – if they allow the administration of trusts within their state (i.e. by trustee(s) resident in the member state).

If the country is not an EU member state, it is not mandatory for non-trust law countries under the FATF to require trustees residing in their country to obtain and hold BO information on trusts. Nonetheless, it is best practice to incorporate and apply such a provision in non-trust law countries: first, to understand the activity of trusts administered within their jurisdiction; and second, to ensure effective international cooperation under the FATF standards when such information is requested by a foreign counterpart regarding a trustee resident in a non-trust law country.

Under the OECD’s CRS, if a country is a CRS participating jurisdiction (whether it is a trust law country or non-trust law country), the requirement to obtain and hold information on the beneficial owners of a trust is imposed on trusts which qualify as Reporting Financial Institutions under the CRS and are resident in the participating jurisdiction (i.e., if any one of their trustee(s) is a resident in the jurisdiction).[12]

The FATF standards and the AMLD5 also differ in the disclosure requirements that are imposed on trustees. The AMLD5 goes beyond the FATF standards in requiring trustees entering into a business relationship or carrying out occasional transactions above the threshold to not only disclose their trustee status to financial institutions and DNFBPs, but to also disclose information on all the beneficial owners of the trust. Again, the approach taken by the AMLD5 is a better approach to ensuring accurate BO information is provided and held by reporting entities, imposing a two-way obligation on both trustees and reporting entities rather than imposing a requirement only on reporting entities to collect and hold such information.

Financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions

Under both the FATF standards and the AMLD5, financial institutions and DNFBPs are required, as a part of their customer due diligence (CDD) checks, to identify and take reasonable steps to verify the identity of the beneficial owners of trusts. Accordingly, the majority of countries have imposed this requirement on their financial institutions and DNFBPs. In fact, financial institutions and DNFBPs are the main source of BO information on trusts when they establish any business relationship with these reporting entities, for in the majority of jurisdictions trusts are still not required to be registered.[13] However, there are two main issues that have been identified in the FATF mutual evaluations with the application of these requirements:

- the information that has been obtained and held by the financial institutions and DNFBPs is not always up to date; and

- it is difficult for competent authorities to get hold of this BO information in a timely manner from financial institutions and DNFBPs, as there are deficiencies in the legal framework.[14]

Central beneficial ownership register of trusts

The FATF standards do not require countries to establish a central register for trusts, although it is one of three complementary approaches identified by the FATF as best practice.[15] However, establishing a central register of BO of trusts, similar to the register for legal persons, is something that is already a requirement under the AMLD5. As the AMLD5 is the only regulatory framework currently requiring central BO registers of trusts, this will be explored in more detail in the following section (see also, Box 2).

Box 2: AMLD5 requirements for central beneficial ownership registers of trusts

- To establish a central BO register of trusts which shall hold information on trusts where:

- a trustee is a resident in the member state; or

- if the place of residence of the trustee is outside the EU, a trustee enters into a financial relationship in the name of the trust in the member state; or

- if the place of residence of the trustee is outside the EU, a trust acquires real estate in the name of the trust in a member state.

- To provide access to the central BO register of trusts to:

- competent authorities and Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs), without any restriction;

- obliged entities, within the framework of their CDD requirements;

- any natural or legal person who can demonstrate a “legitimate interest”; and

- any natural or legal person who files a written request in relation to a trust, where the trust holds or owns controlling interest in any corporate or other legal entity through direct or indirect ownership.

- To set minimum BO data details that should be made available to the public or a third party, i.e. the name, the month and year of birth, the country of residence, and the nationality of the beneficial owner, as well as the nature and extent of beneficial interest held in the trust.

- To require reporting entities and, possibly, the competent authorities of the EU member state to report any discrepancies in the BO register.

- To grant an exemption, in exceptional circumstances and on a case-by-case basis, to protect the BO information on trusts from public disclosure (e.g. to mitigate personal safety risk), and to establish proper mechanisms for assessing and granting such exemptions.

Specifically, there are two provisions in the AMLD5 that require further discussion: the scope of and access to the register.

Scope of the register

The AMLD5 has widened the scope of the trusts that are required to be registered in the central BO register. In the majority of jurisdictions that require the registration of trusts, registration is only the case if a trustee is resident in the respective jurisdiction or the trust has any tax liability.[16] This has been identified as a major loophole which can be exploited by criminals by re-locating the administration of their trust outside a country imposing such a registration requirement.[17]

The AMLD5 now provides that the requirement for the registration of a trust is triggered when the trust is administered in the EU member state; engages in a business relationship; or acquires real estate in the respective EU jurisdiction. Although this is a welcome provision, there is still scope for further improvement. To achieve better effectiveness of the central BO register for trusts, jurisdictions should require the registration of trusts whenever:

To give an example, the UK transposed the AMLD5 prior to leaving the EU, so a trust that is created and governed by the law of the UK is not required to register in the UK central BO register of trusts if its trustee(s) is not resident in the UK, does not hold any UK assets, or has no tax liability in UK, even if the settlor was a UK resident and domiciled in the UK when the trust was settled, or if the settlor and/or the life interest beneficiary is a UK resident and pays tax on the income and gains. Such a trust might be engaged in criminal activities outside the UK, but the UK will have no details on record for this trust in the register.

The AMLD5 also does not precisely define the term “business relationship”, which according to Andres Knobel should be defined broadly to include, for instance, “opening a bank account, providing goods or services, or having any type of operations in the [respective EU state].”[18] In the UK, the term has been interpreted to include business relationships with any UK service providers that are subject to UK AML/CFT law and regulations. This includes, for instance, banks, investment managers, lawyers, accountants, tax advisers, trust and company service providers, and real estate agents. This is a very important provision that should be followed by all countries to prevent trusts from posing financial crime risks to the jurisdiction.

Access

Unlike the requirements for central BO registers for legal persons, the AMLD5 does not require the central BO register for trusts to be made public. It provides that the BO information on trusts should be made available only to those natural or legal persons who demonstrate a legitimate interest.

Due to the nature of trusts being private arrangements, there has always been a strong reluctance and argument against the public disclosure of the BO information of trusts. Generally, these arguments are based on the right to privacy, the complexity of registering the BO information of trusts, and that the beneficiaries may not know about the existence of a trust.[19] It has also been argued that since most trusts are legitimate and involve private family matters, such obligations would be too cumbersome.[20] This argument against the public disclosure of the BO information of trusts has also been upheld by a decision dated 21 October 2016 of the French Constitutional Court (Conseil Constitutionnel), which cancelled the Public Register of Trusts that came into force in France in May 2016 (see Box 3).[21]

Box 3: France, Constitutional Court, Decision 2016-591 QPC of 21 October 2016[22]

In France, the Public Register on Trusts became effective on 10 May 2016. A case was brought to the French Constitutional Court by a US citizen, who was a tax resident in France, questioning whether the public nature of the Register of Trusts complied with the French constitution, especially regarding the right to privacy guaranteed by Article 2 of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. The Court in this case had to consider two constitutional principles: a) the objective of this register to fight tax evasion; and b) the right to privacy protected by Article 2 of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

The French Court ruled against the public disclosure of the register of BO on the grounds that: "the Parliament, which did not specify the quality nor the motives that justify consulting the register, did not limit the people that have access to the information in this register, placed under the responsibility of the tax administration."

In those circumstances, the court commented in this decision that: "these disputed provisions have a clearly disproportionate effect on the right to respect for private life with regard to the objectives sought."

The Constitutional Court finally ruled that unrestricted and unregulated access to the register of trusts was manifestly disproportionate to the right to privacy. France has made its BO register of legal persons public in line with AMLD5 requirements.

On the other hand, civil society groups have advocated for BOT in the register of trusts similar to the register of legal persons. Their main argument is based on the very nature of trusts, which makes them attractive for criminal abuse – whether it be to commit financial crime (such as laundering the proceeds of corruption or tax evasion) or to fraudulently protect assets from creditors (for example, in cases of bankruptcy, financial setbacks, family disagreements, divorces, and lawsuits). It has been argued that if the existence and operation of trusts affects third parties in any way, they should be registered and, if not, they should remain private.[23] Similar to the case for the public BO register for legal persons, it has been argued that the public disclosure of the BO of trusts will: support law enforcement in the detection and prosecution of financial crime; act as a powerful deterrent for criminals; and help in tackling corruption.[24]

The AMLD5 appears to have taken a middle approach by allowing public access to the BO information when a legitimate interest can be demonstrated. The term legitimate interest is, however, not defined in the directive and is left to the discretion of the states. Nonetheless, the directive provides that when defining the term, member states should include “preventive work in the field of anti-money laundering, counter terrorist financing and associate predicate offences undertaken by non-governmental organisations and investigative journalists” in their definitions.[25] How narrowly or broadly this term is interpreted by jurisdictions in their domestic law and the procedure laid down to prove legitimate interest remains to be seen, and will determine the accessibility of the BO information of trusts to third parties. The interpretation might result in making this information almost inaccessible to third parties,[l] or it might become a useful clause for third parties, including journalists and non-profit organisations, to access and analyse the relevant information to combat financial crime in similar ways they have done using public registers of BO of legal persons.[m]

Despite the limited public access to the central BO register of trusts provided in the AMLD5, a few EU countries have already gone beyond the requirements of the directive to provide public access to the BO information on trusts to promote transparency. Box 4 outlines the approaches of a few countries who have transposed the AMLD5 to accessibility of their BO information on trusts.

Box 4: Examples of access to beneficial ownership registers of trusts or similar legal arrangements

- Austria and Germany: Austria and Germany have gone beyond the transparency requirements of the AMLD5 by making BO information on private foundations available to the general public.[26]

- Ireland, Malta, and the UK: Access to the central BO register of trusts is only available to those who demonstrate a “legitimate interest”.

- Belgium: Belgium does not have a separate centralised register on BO of trusts, but if a trust or similar legal arrangement appears in the ownership structure of a legal person, the central BO register on legal persons only displays the details of a trust or similar legal arrangement to the public, whilst the information on the beneficial owners of such trust or similar legal arrangements is only available to the natural or legal persons who can demonstrate a “legitimate interest”.[27]

Beneficial ownership of trusts within disclosure regimes for legal entities

A question that often arises when discussing the BOT of trusts is how it would interact with the existing BO disclosure regimes for legal entities and what practical issues might arise. This is analysed below by dividing the question into situations where:

- trusts appear in the ownership structure of a legal entity; and

- companies appear in the ownership or control of a trust.

A comprehensive exploration of how different jurisdictions with beneficial ownership registers of legal persons have dealt with these issues is not within the scope of this paper. Rather, this section covers some of the decisions faced by implementers using scenarios.

Trusts in the ownership structure of a legal entity

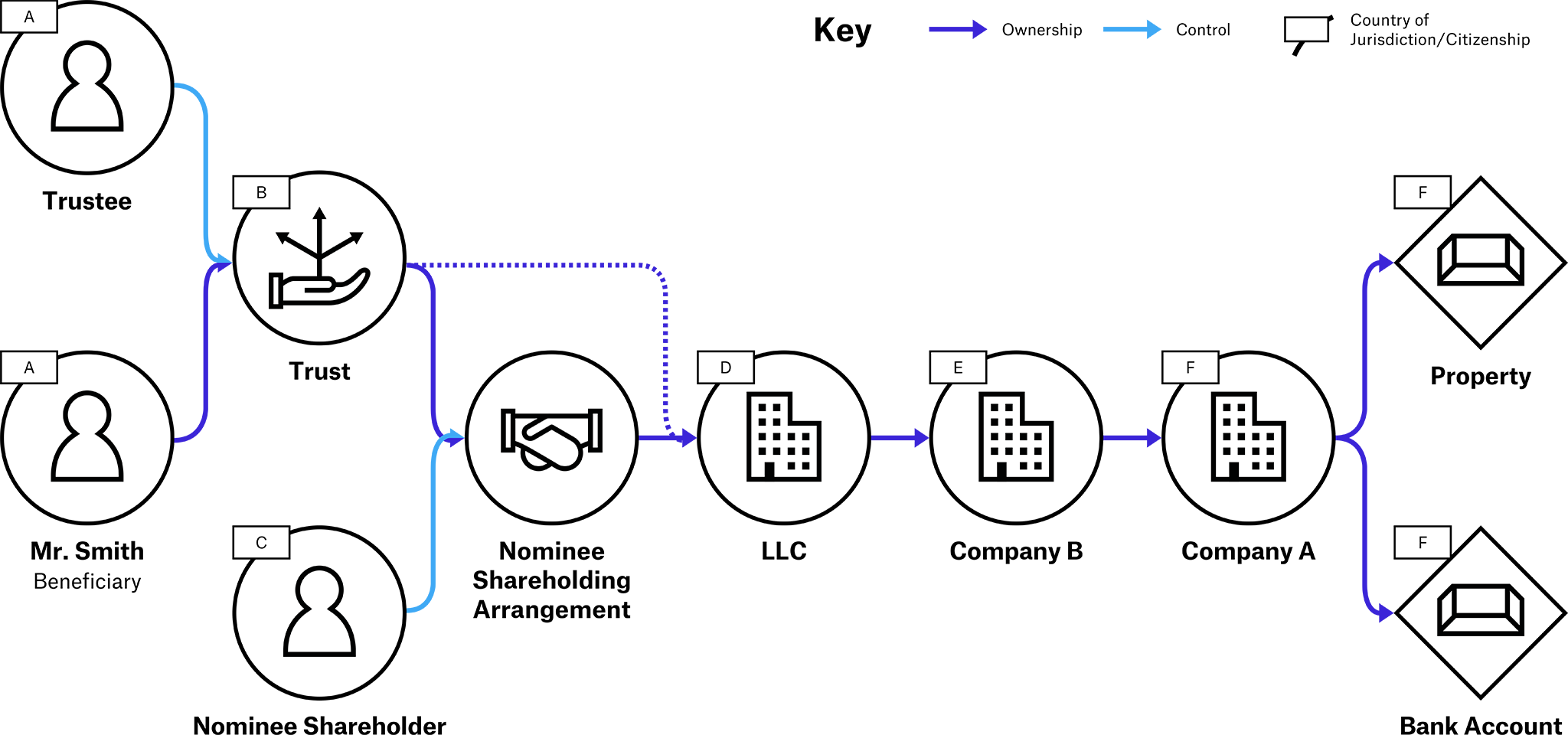

Trusts are sometimes used as the last layer of secrecy in a complex corporate structure, which has been primarily designed to disguise a criminal’s connection to illicit funds. Layering trusts with shell companies in different jurisdictions, as illustrated in Figure 1 below, will obfuscate BO and create a complicated and confusing trail between the criminal activities and proceeds. Arrangements are often made to span multiple jurisdictions, with trust assets, trust, and company service providers (TCSPs) and management companies each located in a different country.

Figure 1. Trust in a complex system of legal vehicles

Adapted from: OECD (2019)[28]

If a trust appears in the ownership structure of a legal entity, the question that is often asked is: what information should be obtained and registered in the BO register for legal entities? In line with international definitions of what constitutes a beneficial owner of legal entities and trusts, rather than the name of the trust, all natural persons party to a trust should be identified in the register. Due to the challenge of knowing who actually controls and benefits from trusts because of their endless variety and complexity,[29] thresholds are not relevant, and this includes: a) settlor(s); b) trustee(s); c) protector(s) (if any); d) beneficiaries or class(es) of beneficiaries; and e) any other natural person exercising control over the trust. As with other natural persons, all the relevant details of these natural persons who are the beneficial owners of the trust should be registered, including the nature or means of the ownership/control relationship (e.g. by being a trustee of the trust). However, depending upon the jurisdiction’s domestic law, the beneficial owners of the trust may apply for protection of certain information from disclosure to the public.

Implementers may also have to address some other practical questions or challenges in registering the BO data of trusts, both on the BO register of legal persons and the BO register of trusts (if established). These include, for instance, who should be recorded as a beneficiary in the register:

- In the case of a discretionary trust, for example, where the beneficiaries only hold contingent interest in the trust. In such instances, the UK’s approach is to highlight the type of trust in the register but not record the details of the contingent beneficiary on the register until the contingency is satisfied. Once the contingency is satisfied or the trust property is distributed, the details of the beneficiary should be recorded on the register.

- In the case of a class of beneficiaries who are not yet specifically named: for example, grandchildren of person A. The UK’s approach is not to identify members of a class of beneficiaries in the register unless they receive a benefit from the trust. Whether such an approach is sufficient to ensure the BOT of trusts is debatable.

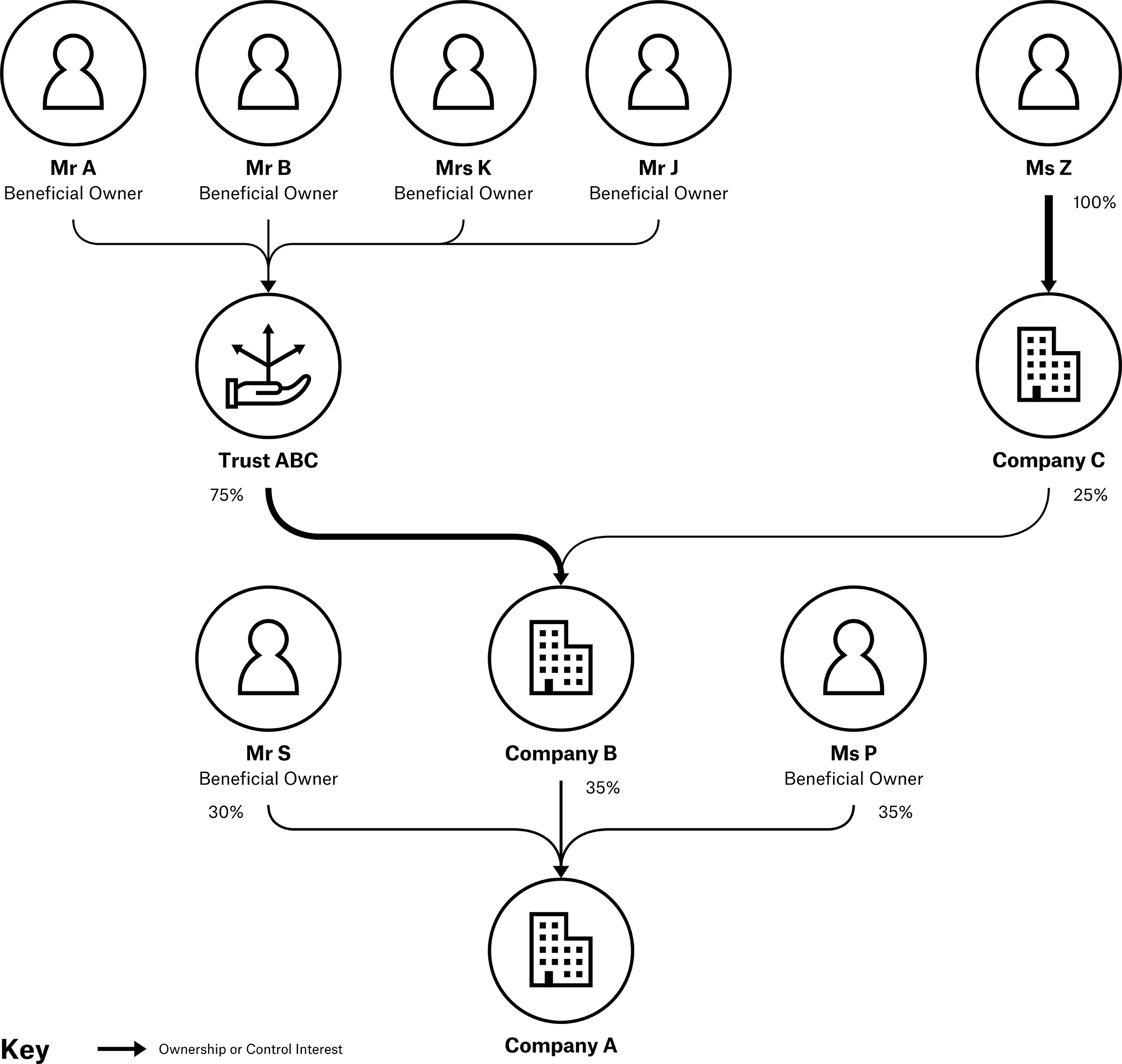

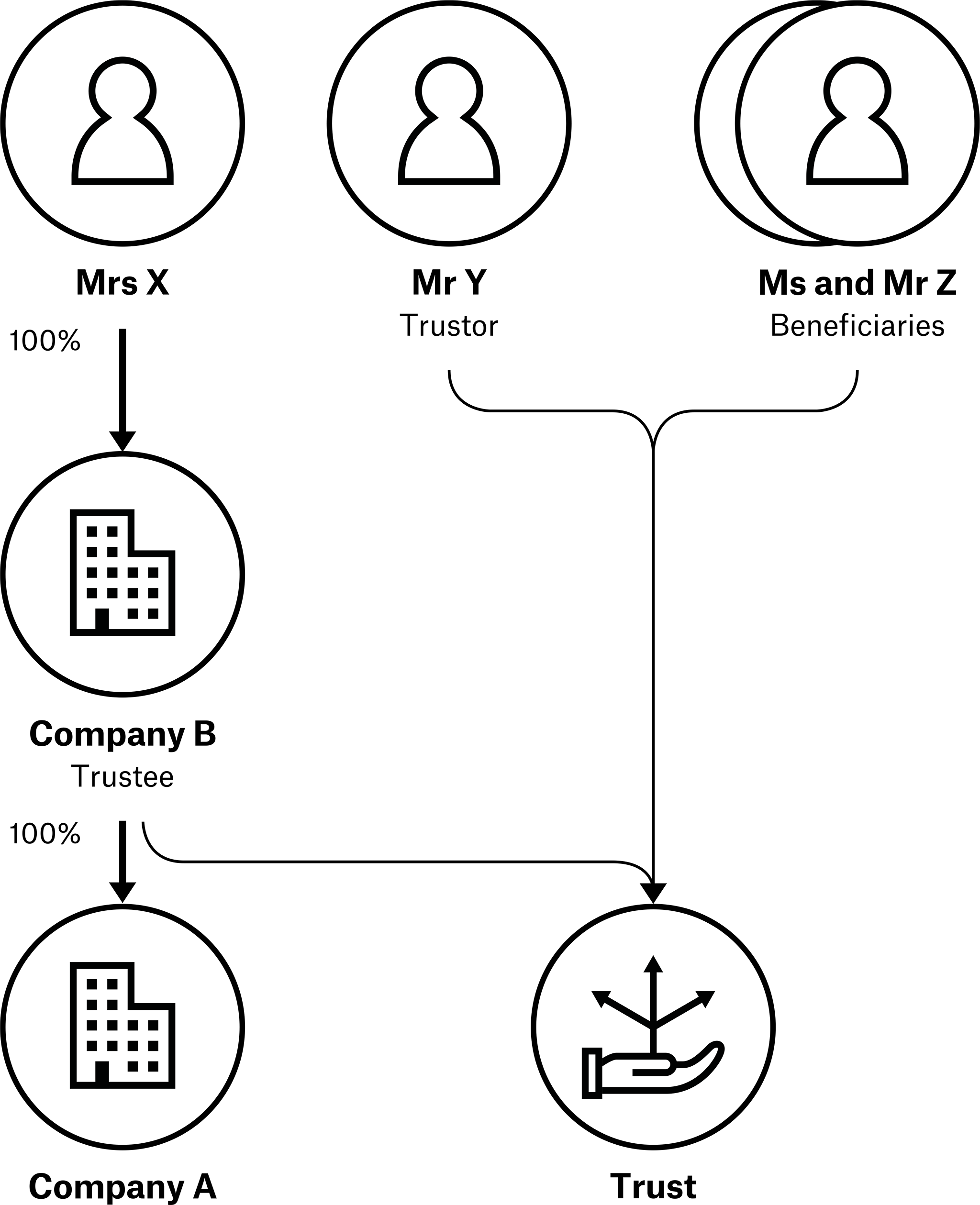

Figure 2. Identifying beneficial owners of Company A with a trust in a chain of ownership

To illustrate, in Figure 2 a trust appears in the ownership structure of Company A, as it indirectly holds shares in the company through Company B. In the UK, if the trust satisfies the conditions to require registration to the trust register, all parties would be declarable as beneficial owners. For the beneficial ownership of legal entities, the UK takes the approach that the same conditions for disclosure apply for trusts as they do for individuals. The trust satisfies one of the conditions for beneficial ownership (or “significant control”, in the UK) of a legal entity; namely, directly or indirectly holding more than 25% of the shares in the company, as the trust owns 26.25% of Company A indirectly. While all parties to Trust ABC are beneficial owners of Company A, the UK does not require the declaration of all the parties to a trust when it appears in the ownership structure of a company in the UK’s BO register (the Persons of Significant Control (PSC) register), but only the trustee(s) and the person(s) who exercise(s) ultimate effective control or influence over the activities of the trust (which could be a settlor, a beneficiary, or a protector). It can be argued that in a BOT of legal persons regime with full public access, all parties to the trust – all being beneficial owners – should be declared.

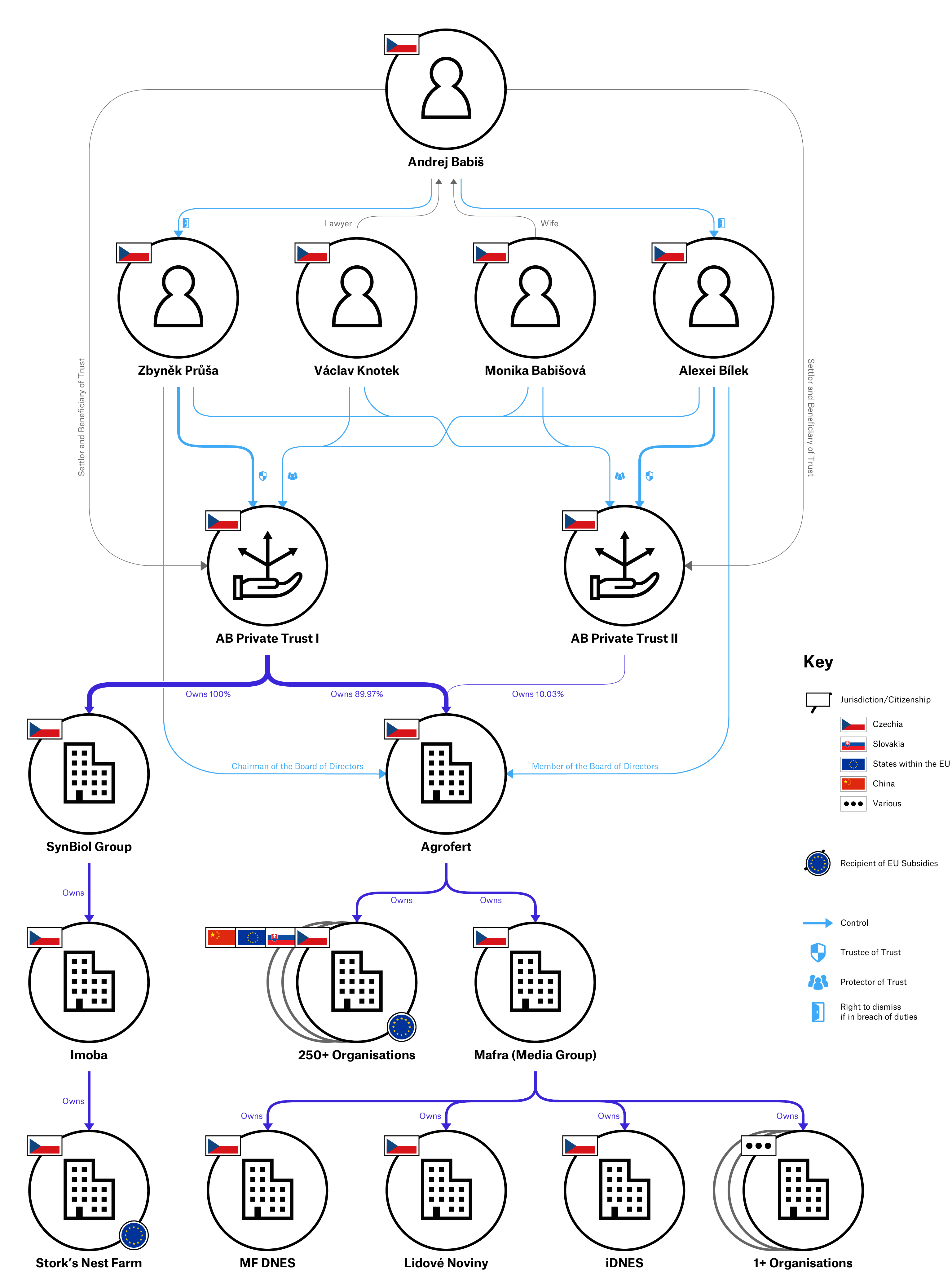

Box 5: Trusts in a corporate ownership structure in Slovakia[30]

Before entering politics in 2011 on an anti-corruption platform,[31] current Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš worked in the private sector and founded the Agrofert Group in 1993. Agrofert now has more than 250 subsidiaries, including two of the largest Czech newspapers, MF DNES and Lidové noviny, as well as the Mafra media group, which owns, iDnes, the most visited Czech news server.[32]

Following the introduction of Czech conflict of interest legislation that prevents members of government and other public officials from having a controlling interest in news media, Babiš transferred his sole ownership of the Agrofert Group to two trust funds, AB private trust I, owning 565 shares (89.97%), and AB private trust II, owning 63 shares (10.03%).[33] Agrofert is currently active in 18 countries in 4 continents,[34] and as such it is registered in both the Czech Republic as well as Slovakia, where it is a market leader in agriculture and food processing.[35]

Following research on the Slovak BO register in 2018, Transparency International (TI) Slovakia uncovered that Babiš was disclosed as one of five beneficial owners by Agrofert Slovakia.[36] In response, Agrofert claimed that “Mr. Babiš is not the controlling entity of the Slovak companies of the Agrofert Group.”[37] This was contested by TI Slovakia, drawing attention to the fact that Babiš is the only beneficial owner that has the power to remove all other listed beneficial owners – the trustees.[38] Additionally, he is listed as a beneficiary in the certified disclosure document; the trust funds are set up so that the shares will return to him when he terminates his public office.[39] Besides potentially violating the Czech Conflict of Interests Act, Babiš could have violated EU laws regarding firms being owned by politicians not being eligible to receive EU funding,[40] as Agrofert subsidiary companies received EU subsidies both before and after Babiš transferred his ownership to the two trusts in 2017.

A recent EU audit has found that: “Considering […] that Mr Babiš has defined the objectives of the Trust Funds […], set them up and appointed all their actors, whom he can also dismiss, it can be assessed that he has a direct, as well as an indirect decisive influence over the Trust Funds. Based on this assessment, the Commission services consider that, through these Trust Funds, Mr Babiš indirectly controls the parent company AGROFERT group […]” and was found to be in violation of the EU’s Conflict of Interests Act.[41]

Agrofert beneficial ownership structure in 2020

Source: Early impacts of public registers of beneficial ownership: Slovakia (2020)[42]

Corporate ownership or control of trusts

If in the ownership structure of a legal entity it becomes apparent that a legal entity is one of the parties of a trust, such as a corporate trustee or corporate beneficiary, the beneficial owners of a trust would be the settlor(s), trustee(s), protector(s), beneficiaries or class of beneficiaries, and natural persons who own or control the company that is party to the trust, either as a corporate trustee or a corporate beneficiary.

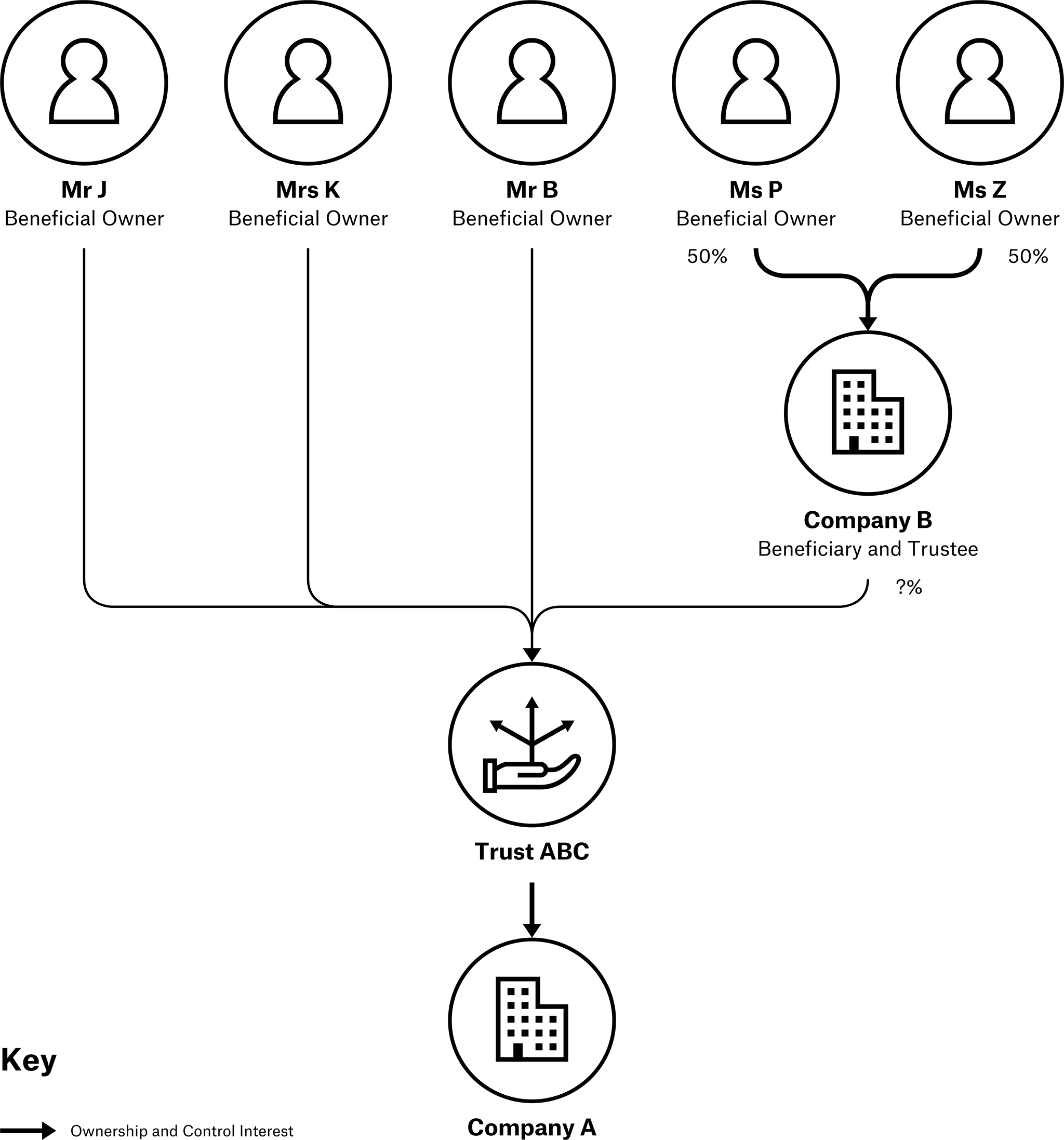

Figure 3. Identifying beneficial ownership of Company A with a company as party to the trust in a chain of ownership

In the scenario in Figure 3, implementers in jurisdictions with thresholds for the BO of legal persons may have to address the question of who would be declarable as BO if the percentage ownership and control of Ms Z or Ms P dropped beneath the threshold (e.g. 25% in the UK). According to UK guidance, “if a legal entity […] controls the trust [which would be a PSC of the company if it were an individual], then the ownership chain will need to be explored further until an individual […] with majority ownership of that legal entity is identified, or it is established that none exists”.[43]

Figure 4. Identifying beneficial owners of Company A with a corporate party to a trust in a chain of ownership

In the scenario in Figure 4, a legal entity Company B appears as a trustee to a trust, while also being a shareholder of Company A. In this scenario in the UK, while the trust and all its parties may need to be registered in the trust register if the trust satisfies any of the requirements, only Ms X would be required to be declared as a beneficial owner to Company A in the PSC register, indirectly owning 100% of its shares. Other countries, such as Austria, take a different approach. Namely, that in this case the trustor and beneficiaries also all need to be declared as beneficial owners to Company A, as the trust as a whole exercises control over Company A.

Access

A question that requires further probing here is: if the central BO register of legal entities is publicly accessible, would that imply that the BO information of any trust that features in the ownership structure of any entity would also be publicly available? If that would be the case, would it result in the infringement of the right to privacy? To deal with this situation, different countries have taken different approaches. In Belgium, as discussed earlier, the information on the BO of trusts that appear in the ownership structure of a legal entity is not made public, but is only accessible to those who demonstrate a legitimate interest. This approach has been adopted to strike a balance between the right to privacy and benefits of public disclosure. On the other hand, in the UK, the central BO register on legal entities only requires registering the information on the trustee or any “other person with significant control over the trust”. No information is required to be provided about the other parties of the trust on this register, which makes it deficient in the sense that it does not register all the beneficial owners of the trust, as defined by international standards. Additionally, in practice, information about trusts and trustees appears to be disclosed in an inconsistent way when people disclose trusts as part of a company’s ownership structure.

As required by the AMLD5, the UK has incorporated a provision in the law to provide accessibility on the BO information of trusts recorded in the trusts’ register to third parties where the registered trust has a controlling interest in a non-EEA legal company. In such an instance, the person seeking information on the trust does not have to demonstrate legitimate interest, but has to identify the specific non-EEA legal entity in question and its relationship with the trust which holds the controlling interest. In addition, the person might have to demonstrate how the request is in line with the objectives of the directive – i.e. that it will help to detect or prevent money laundering or terrorist financing, although there are no clear guidelines provided in this regard by the authorities yet. Access is expected from 2022. Therefore, there is currently no data as to the effectiveness of this provision.

Footnotes

[c] The wording used here for the definition of BO of trusts is the one provided by the AMLD5. There is a difference between the FATF and AMLD5 definition of beneficial owners of trusts – the FATF definition does not use plurals for “settlor” and “protector”, as has been used in AMLD5. The approach of AMLD5 is in fact a better approach to cover all settlors and protectors within the scope of the definition, as there might be more than one.

[d] A cascading test is an identification process as provided in the FATF’s “Interpretive Note to Recommendation 10” to determine the existence of at least one natural person as a beneficial owner of a legal person when conducting customer due diligence checks. The process contains three steps which are to be used in succession when a previous step fails to identify the beneficial owner of a legal person. The first step is to obtain and verify the identity of the natural persons who ultimately have a controlling ownership interest in a legal person (whether by shares, voting, property, or other rights). If there is a doubt under the first step as to whether a person(s) with controlling ownership interest is a beneficial owner, or where no natural person exerts control through ownership interests, then the second step is to identify a natural person exercising control of the legal person through other means. Where no natural person(s) is identified under the first or second step, the third and final step is to identify and take reasonable measures to verify the identity of the relevant natural person who holds the position of senior managing official. This might not, however, be the approach taken, or preferred, by all jurisdictions which require the ultimate beneficial owners to be identified rather than compromising with the identification of senior officials as beneficial owners. For the criticism of this approach, see: Knobel and Meinzer, “Drilling down to the real owners – Part 2”, 3.

[e] In a “revocable trust”, a settlor retains the power to change the terms of the trust or revoke it at any time prior to his or her death and thereby retains control over the assets placed in the trust. Whereas, in an “irrevocable trust”, the settlor is generally unable to change the terms of the trust once the trust agreement is executed.

[f] “Discretionary trust” is one that allows the settlor to place the assets under the trust at the discretion of the trustee(s), who will decide who is to benefit and how.

[g] The OECD Commentaries to the CRS provide that “In the case of a trust, the term ‘Controlling Persons’ means the settlor(s), the trustee(s), the protector(s) (if any), the beneficiary(ies) or class(es) of beneficiaries, and any other natural person(s) exercising ultimate effective control over the trust. The settlor(s), the trustee(s), the protector(s) (if any), and the beneficiary(ies) or class(es) of beneficiaries, must always be treated as Controlling Persons of a trust, regardless of whether or not any of them exercises control over the trust. … In addition, any other natural person(s) exercising ultimate effective control over the trust (including through a chain of control or ownership) must also be treated as a Controlling Person of the trust with a view to establishing the source of funds in the account(s) held by the trust, where the settlor(s) of a trust is an Entity, Reporting Financial Institutions must also identify the Controlling Person(s) of the settlor(s) and report them as Controlling Person(s) of the trust. For beneficiary(ies) of trusts that are designated by characteristics or by class, Reporting Financial Institutions should obtain sufficient information concerning the beneficiary(ies) to satisfy the Reporting Financial Institution that it will be able to establish the identity of the beneficiary(ies) at the time of the pay-out or when the beneficiary(ies) intends to exercise vested rights.” (Standard for Accounting Exchange of Information in Tax Matters, OECD, (2nd edn, OECD Publishing), 2018, 198-199)

[h] Here, it could be argued that when the FATF Recommendation 25 states “adequate, accurate and timely” information on BO of trusts, it implies information on all settlors and/or protectors, if there are more than one, OR that the FATF Recommendation 25 should be interpreted as a “minimum” requirement with best practice to disclose all settlor(s) and/or protectors. Nonetheless, the uncertainty it might result into when the FATF standards are transposed into national law cannot be overlooked.

[i] Administration of a trust in a member state is defined as the trustee being a resident in the member state.

[j] The expression “non-trust law countries” is used for those countries which do not allow the creation of trusts or similar legal arrangements under their domestic law. Such jurisdictions need not necessarily prohibit foreign law trusts from operating within the jurisdiction.

[k] The expression “trust law countries” has been used for those countries which allow the creation and recognition of trusts or similar legal arrangements under their domestic law.

[l] For instance, a Global Witness report (2017) has given a few country example of Czech Republic, Italy, and Latvia as to how narrowly this term “legitimate interest” was interpreted in their domestic law, as required earlier under the EU 4AMLD in the case of central BO register of legal persons (Worthy, “Don’t take it on trust”, 13). In Barbados, for instance, the BO information on trusts will only be disclosed by court order, in any civil or criminal proceedings (FATF Mutual Evaluation of Barbados, 2018).

[m] In the UK, for instance, the term “legitimate interest” has not been defined. However, a criteria to determine “legitimate interest” has been provided under Regulation 45ZB(11) of the Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020, which provides that a person may request to access the BO information of a trust if a person can demonstrate that the person is involved in an investigation into suspected money laundering or terrorist financing activity and there is a reasonable suspicion that the trust is being used for money laundering or terrorist financing (see also: Becky Bailes and Alexander Erskine, “The UK Trust Register – where are we now?”, Lexology, 27 October 2020), https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=38b87fca-4966-47d1-b9f6-2f54142b5388). Whether that includes non-governmental organisations and investigative journalists is not clear. The perception, however, is that criteria to demonstrate “legitimate interest”, as provided in the Regulations, is quite high for anybody to meet before the information can be accessed (see also: Sam Epstein, Jennifer Smithson, and Ethan Yu, “5MLD: major changes to the UK trust register”, Tax Journal, 6 November 2020, https://www.macfarlanes.com/media/3581/tax-journal-5mld-major-changes-to-the-uk-trust-register.pdf.

Endnotes

[7] Guidance on Transparency and Beneficial Ownership, FATF, (Paris: FATF), October 2014, 9, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Guidance-transparency-beneficial-ownership.pdf.

[8] See: FATF Recommendations 2012 (as amended in October 2020), Interpretive Note to Recommendation 10, 60; EU AMLD, Article 31(1).

[9] A similar provision has also been incorporated in the OECD, Standard for Automatic Exchange of Financial Information in Tax Matters: Implementation Handbook (2nd edn, Paris: OECD, 2018), para 266, which states that “the definition of [BO for trusts] excludes the need to inquire as to whether any of these persons can exercise practical control over the trust.”

[10] Knobel, “Beneficial ownership verification: ensuring the truthfulness and accuracy of registered ownership information”, 20.

[11] Ibid, 198.

[12] Standard for Accounting Exchange of Information in Tax Matters, OECD, 199.

[13] As discussed below, the AMLD5 requires its member countries to establish a central BO register of trusts, but there is no such requirement under the FATF standards. To gain further understanding on the treatment and registration of trusts in different jurisdictions, see: Chhina, “An introduction to trusts”.

[14] These conclusions have been drawn based on the analysis of the FATF Mutual Evaluation Reports of various jurisdictions. See, for instance: Mutual Evaluation Reports of Zimbabwe (2016), 155; Trinidad and Tobago (2016), 161; Thailand (2007), 176; Nicaragua (2017), 140; Myanmar (2018), 151; Morocco (2019), 164; Mauritius (2018), 175; Malaysia (2015), 194; Jamaica (2017), 143; Georgia (2020), 223; Bangladesh (2016), 152; Barbados (2018), 138.

[15] See: FATF Recommendations 2012 (as amended in October 2020), Interpretive Note to Recommendation 25, 91.

[16] For detailed discussion on the registration requirements of trusts, see: Chhina, “An introduction to trusts”.

[17] Worthy, “Don’t take it on trust”, 3; Knobel, “‘Trusts: Weapons of Mass Injustice?’ A response to the critics”.

[18] Andres Knobel, “The EU’s latest agreement on amending the anti-money laundering directive: at the vanguard of trust transparency, but still further to go”, Tax Justice Network, 9 April 2018, https://www.taxjustice.net/2018/04/09/the-eus-latest-agreement-on-amending-the-anti-money-laundering-directive-still-further-to-go/.

[19] See: Knobel, “‘Trusts: Weapons of Mass Injustice?’ A response to the critics”.

[20] Ibid.

[21] To read a further analysis of the French ruling and the right to privacy argument, see: Andres Knobel, “Beneficial Ownership and Disclosure of Trusts: Challenging the Privacy Argument”, Tax Justice Network, 17 December 2016, https://www.taxjustice.net/2016/12/07/beneficial-ownership-disclosure-trusts-challenging-privacy-arguments/.

[22] See: Stephanie Auferil and Arnaud Tailfer, “Register of trusts and privacy: French case in perspective with the fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive Register” (2018) 24(10) Trust & Trustees 968.

[23] See: Worthy, “Don’t take it on trust”; Knobel, “‘Trusts: Weapons of Mass Injustice?’ A response to the critics”; “Navigating a path to trust and transparency: Can Ultimate Beneficial Ownership Registers help prevent financial crime?”, PwC, 2016, https://www.pwc.co.uk/forensic-services/assets/navigating-a-path-to-trust-and-transparency.pdf.

[24] Ibid.

[25] EU 5AMLD, L156/51.

[26] P. Panico, “Private Foundations and EU beneficial ownership registers: towards full disclosure to the general public?”, 2020, 26(6) Trusts & Trustees 493.

[27] Ibid.

[28] A Beneficial Ownership Implementation Toolkit, OECD and IDB, March 2019, 5.

[29] To gain further understanding on different types of trusts and their complexities, see: Chhina, “An introduction to trusts”.

[30] For the full story, see: Tymon Kiepe, Victor Ponsford, and Louise Russell-Prywata, “Early impacts of public registers of beneficial ownership: Slovakia”, OO, September 2020, https://www.openownership.org/uploads/slovakia-impact-story.pdf.

[31] “Czech prosecutors drop fraud probe into PM Andrej Babis”, DW, 2 September 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/czech-prosecutors-drop-fraud-probe-into-pm-andrej-babis/a-50255477.

[32] “About Agrofert”, Agrofert, n.d., https://www.agrofert.cz/en/about-agrofert; Yveta Kasalická, “The new Czech media owners”, Progetto Repubblica Ceca, 28 July 2014, http://www.progetto.cz/i-nuovi-padroni-dei-media-cechi/?lang=en; Michal Černý, “Zpravodajci na českém webu: přehled zpravodajských serverů”, Lupa, 13 February 2008, https://www.lupa.cz/clanky/zpravodajci-na-ceskem-webu-prehled/; “About the company”, MAFRA, n.d., https://www.mafra.cz/english.aspx.

[33] Daniel Morávek, “Babiš převedl Agrofert do svěřenských fondů, firma se mu ale vrátí”, Podnikatel, 3 February 2017, https://www.podnikatel.cz/clanky/babis-prevedl-agrofert-do-sverenskych-fondu-firma-se-mu-ale-vrati/; “Shareholder informed the management of the companies AGROFERT and SynBiol on the transfer of shares into Trusts”, Agrofert, 3 February 2017, https://www.agrofert.cz/en/events-and-news/shareholder-informed-the-management-of-the-companies-agrofert-and-synbiol-on-the.

[34] “About Agrofert”, Agrofert.

[35] Ibid.

[36] David Ondráčka, “Andrej Babiš is our controlling person (beneficial owner), says Agrofert”, TI, 22 June 2018, https://www.transparency.org/en/press/andrej-babish-is-our-controlling-person-czech-republic; “Register of public sector partners”, Ministry of Justice of the Slovak Republic, 1 February 2017, https://rpvs.gov.sk/rpvs/Partner/Partner/HistorickyDetail/7859.

[37] “Rebuttal of misinformation from Transparency International”, Agrofert, 19 June 2018, https://www.agrofert.cz/en/events-and-news/rebuttal-of-misinformation-from-transparency-international.

[38] Ondráčka, “Andrej Babiš is our controlling person (beneficial owner), says Agrofert”.

[39] Morávek, “Babiš převedl Agrofert do svěřenských fondů, firma se mu ale vrátí”.

[40] Specifically Article 57 of Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 966/2012 and Article 61 of Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2018/1046; European Parliament, “European Parliament resolution of 14 September 2017 on transparency, accountability and integrity in the EU institutions”, 14 September 2017, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2017-0358_EN.html.

[41] “Audit of the functioning of the management and control systems in place to avoid conflict of interest as required by Articles 72-75 and 125 of Regulation (EU) No 1303/2013 and Articles 60 and 72 of Regulation (EC) No 1083/2006”, European Commission, 2019, 19, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/reports/cz_functioning_report/cz_functioning_report_en.pdf.

[42] Kiepe, “Early impacts of public registers of beneficial ownership: Slovakia”, 11.

[43] “Register of people with significant control: Guidance for people with significant control over companies, Societates Europaeae, Limited Liability Partnerships and eligible Scottish partnerships”, Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), June 2017, 30, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/753028/170623_NON-STAT_Guidance_for_PSCs_4MLD.pdf.