The use of beneficial ownership data by private entities

Findings

The following section outlines the main findings of the research and presents the survey responses. The first section summarises the current use of BO data by the surveyed companies. The second section covers respondents’ views on BO data use in the future.

Current use of beneficial ownership data in the private sector

A wide range of private entities reported using BO data, across all industries surveyed. The main drivers for use vary across each group. The following section looks at the current use of BO data across each entity group identified in the methodology.

Group 1 entities: Beneficial ownership data service providers

BO data service providers are private companies that offer customers – usually other private entities – BO data on customers, suppliers or other entities they are dealing with. These providers often use labour and cost-intensive – sometimes manual – processes to create records on BO when sources are of poor quality (see Figure 1 below). In these cases, the providers add a great deal of value to the data they ingest, clean, and provide. In recent years, there has been a proliferation of these service providers, driven both by demand and the growing availability of information on company ownership. Their offerings are augmented by advances in data science that make the data easier to use in decision-making.

BO data service providers draw their data on companies from government registers as well as government and intergovernmental sources, such as lists of politically exposed persons (PEPs), and of UN and trade sanctions. BO data service providers assist clients by making the data available as structured data, using standardised formatting in a digital and often machine-readable format. They usually offer the data cleaned and note where it may have errors (such as unusual entries for given fields) or outdated entries. The more advanced products offer cross-checking information against data in other systems, government registers, and other publicly available information. This can include social media, companies’ annual reports, Bloomberg, and other financial data aggregators who themselves draw data from government registers but also clean and cross-check the data with information from other sources.

Different providers offer different products. Whilst some offer services along with the products, others only provide services to use BO data rather than BO data itself. The products and services offered by the providers included in the research are summarised below. Many companies offer more than one of the following:

- Individual searches using the service provider’s interface. Some offer fuzzy search functionality (searching for approximate matches), whilst others offer multiple fields for search terms. The results are generally shown as matches, and include information on what quality or how reliable the data is (a score is sometimes given). This is the most commonly available BO data service.

- Multiple searches and additional data sets. These cross-reference data in government BO registers, other registers, and PEPs and sanctions lists. Some of these search tools may be customised for specific industries and use cases.

- Semi- or fully customised tools that can process a large volume of searches. Some are automatic and integrate with customer management systems and payment or transaction systems, and some provide alerts for further investigation. Many provide reporting for analysis or audit purposes.

- The provision of raw data, for example through an application programming interface (API) for regular, customised data pulls. Customers can purchase and download structured data. Some providers note when data is missing or possibly inaccurate.

- Platforms that allow integration of different processes (such as onboarding and lifetime systems) and data to support compliance and business decision-making. These platforms typically do not provide BO data themselves but allow BO data to be integrated with other data, for instance on sanctions, PEPs, and enforcement. They often provide this against a backdrop of detailed information about jurisdictions, definitions, rules, PEPs, sanctions, and other watch lists to make the data easily usable in compliance and in other business processes.

- Consulting services. Identification of grantees or business partners, due diligence for mergers and acquisitions, and regular or ad hoc risk monitoring are among the range of consulting services that use BO data and that are offered to private entities.

The largest customer segment is the financial services industry: corporate and commercial banks, non-banking financial institutions, and financial technology (FinTech) companies. There is also a growing market for data services customised for niche uses – for example, for investors looking into governance issues of a company in which they are interested in investing.

Beneficial ownership data sources and format

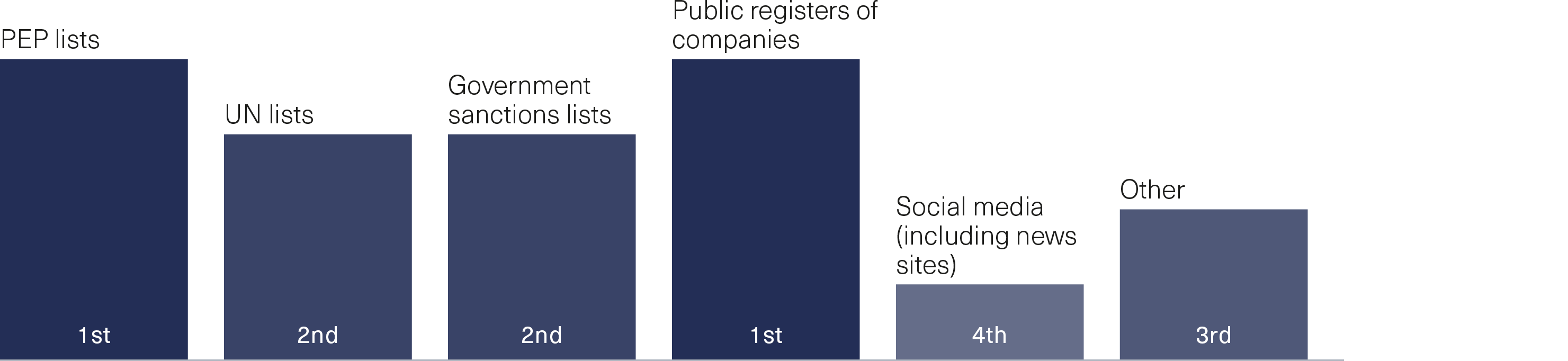

All the BO data service providers surveyed in this study obtain data directly from public registers of companies as well as government PEP lists. Intergovernmental sanctions lists were another source of data, as was social media. Other data sources reported were trade data and data provided by customers or clients themselves (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. From where do beneficial ownership data service providers obtain data?

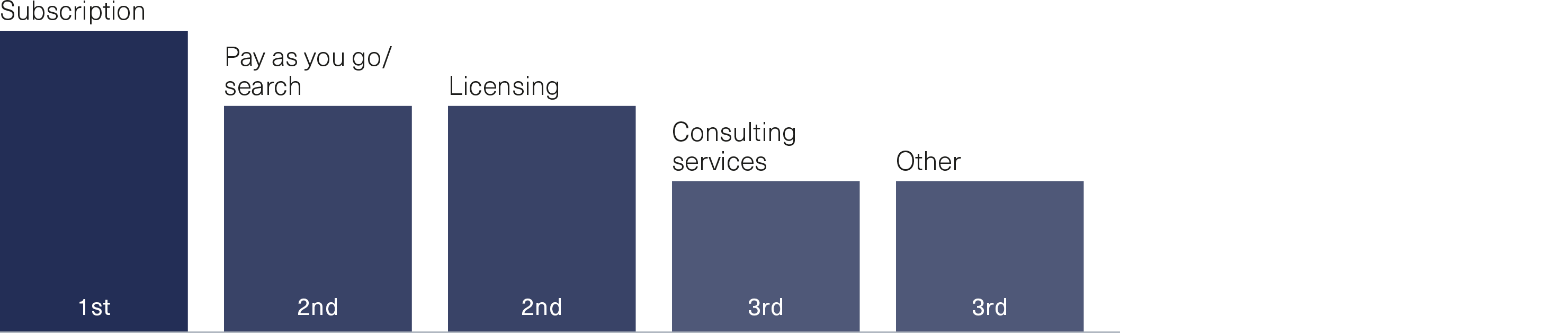

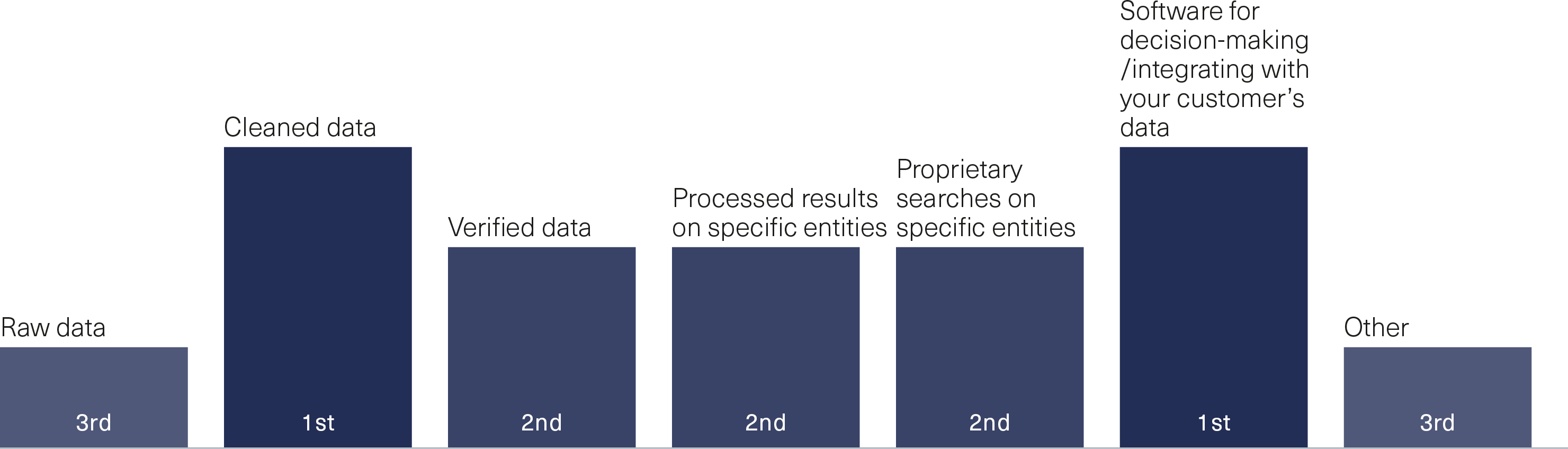

Figure 2. In what forms do beneficial ownership data service providers offer data?

The data from the surveyed service providers is most commonly offered as a subscription service, which all respondents provided, whereby the user could conduct as many searches as offered in a monthly or annual subscription. Many providers offer a licensed version of their product. In some cases, customers can have this customised for their needs and integrated with existing software, such as customer relationship management (CRM), procurement or customer onboarding tools. Others offer simpler pay-as-you-search services via a web interface.

Figure 3. How can customers access their products and services?

Data is least frequently provided by the surveyed companies in raw forms as obtained from sources such as government registers. Most often, service providers supply BO data to users as cleaned data, searchable in pre-set fields, or provide software for using and integrating BO data. Data may be provided as verified data through cross-referencing between different data sets or through the BO data service providers’ own method of flagging incomplete or questionable data.

Challenges in the use of beneficial ownership data

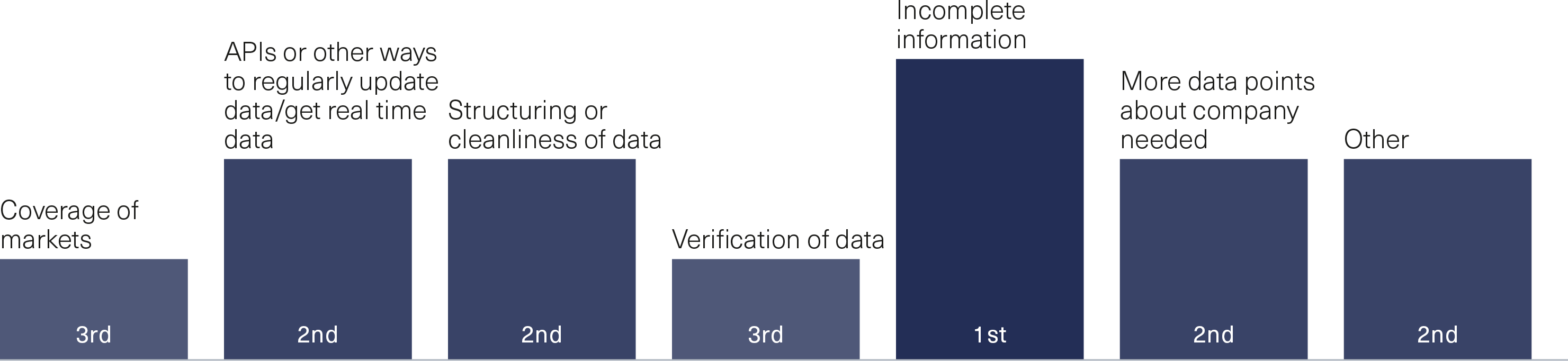

BO data service providers noted many challenges in the access and provision of BO data for their customers. Incomplete information (e.g. missing data or fields that were incorrectly completed) was cited as a challenge by the majority of service providers. Other significant challenges highlighted were the lack of APIs or other means for BO data service providers to obtain updated data quickly and easily, and that the information the data provides about a company is often too limited. Uneven availability of data across markets globally was also mentioned but was less frequently because BO data service providers and their clients know that data is not available equally in all markets. The challenges in integrating BO data that is structured differently in different registers was also noted by one BO data service provider.

Figure 4. Data-related challenges experienced by beneficial ownership data service providers

Secondary research identified a plethora of private companies that provide BO data, which is indicative of large demand for the data and related services. It should be recognised that these companies add significant value to BO data for compliance and other purposes in large part because of current weaknesses in government registers. At the same time, some of these weaknesses present significant challenges for service providers to offer efficient and robust products and services, and to assist their clients in their compliance obligations and other business processes.

BO data service providers are offering increasingly sophisticated tools that can add even greater value to BO data. For instance, some offer a greater customisation of offerings for specific types of users within the private sector, outside of the primary regulatory uses, such as for investors, or for sustainability departments wishing to better understand the relationships of BO with other entities.

Accessibility is a significant issue. Registers do not all offer the same access, even if they are considered public (see Table 3). Many charge fees, require identification and registration, and collect other data from users of the register. Their search functionality may be limited and there are often time delays for approval and limits on the number of searches that can be conducted at a time. Definitions, standards, and rules vary widely across registers.

| BO data... | Yes (no. of countries) | No* (no. of countries) |

|---|---|---|

| is licensed under an open licence (for basic information) | 8 | 19 |

| has registration-free access | 10 | 17 |

| is accessible free of charge | 11 | 16 |

| has API access | 12 | 15 |

| is downloadable in bulk | 13 | 14 |

| is machine-readable | 18 | 9 |

| is searchable by both BO and legal entity | 5 | 22 |

* This includes countries where this was not yet implemented or for which information was not available.

Sources: Licensing, API, bulk download and machine readability: Deloitte[1]; Registration, cost and searchability: Transparency International.[2]

Understanding the data created within each jurisdiction and required by that jurisdiction for compliance is another challenge. Numerous definitions, thresholds, and rules regarding BO exist, which make interpreting data from registers challenging. Additionally, providers highlighted challenges concerning lack of up-to-date BO data in registers:

It depends on the customer, but some require, as ongoing or ad hoc due diligence, that checks or cross-referencing is conducted – the problem is that BO data may only be entered once, and once ownership is changed, this may not be reflected in the data. Also, BO data registers are usually infrequently updated and each country has different timelines for updating, so for companies already known to the customer or user, there is little incentive to look again at BO regularly.[3]

Group 2 entities: Companies that are end consumers of beneficial ownership data for internal business processes

Individual companies are consumers of BO data, often because it is required by regulations. The research identified certain characteristics that have an impact on whether and how the surveyed companies use BO data. These differences, such as the size and market coverage of the company, industry-specific regulations, and industry standards, are discussed in more detail in the following section.

Business drivers for beneficial ownership data use

The initial landscape mapping conducted for this study and the subsequent surveys found that BO data is used within a range of industries, in response to two key business drivers:

- Regulations that mandate the use of BO data. Compliance risk, or a company’s potential exposure to legal sanctions, penalties and reputational damage as a result of its failure to act in accordance with regulations; such as the company being used by actors to launder money.

- Mitigating risks that are not compliance-related by using BO data. These include operational risks and significant reputational risks to individual companies, among others.

The research found that for respondents, the overriding business drivers for the use of BO data comes from regulators and the expanding scope of legal frameworks with which companies must comply. Regulations extend across jurisdictions and overwhelmingly fall under AML legislation, but also cover other issues such as human rights. Industry best practices are also well-developed in many sectors, acting as a kind of (voluntary) set of practices on specific themes, such as environmental practices.

Broader voluntary standards that cut across industries are promulgated by standard setters such as UN agencies, as well as international bodies such as the ISO, which develops voluntary international standards to facilitate trade. Many of these require the use of BO data, for example, in supply chain management, in third-party human rights assessments, and in voluntary anti-corruption measures. For example, the World Economic Forum (WEF) – an organisation with a membership comprising mostly of global enterprises[4] – states that organisations “should obtain ultimate beneficial ownership (UBO) information regarding third parties – even if such an enquiry may not be strictly required by applicable law.”[5]

In addition to using BO data for compliance and avoiding potential sanctions and reputational damage, creating a competitive advantage by using BO data to manage operational risk does not seem to be a strong driver for the use of BO data. Rather, there is a growing trend in voluntary standards around the ESG performance of companies, which is creating incentives to use BO data to gain better insights into suppliers, partners, and investees.

| Industry | Drivers cited in survey responses |

|---|---|

| Commercial banking |

AML compliance: - AML regulations - Client onboarding - KYC obligations - Suspicious activity reports (SARs) - Transaction monitoring - Due diligence of partners |

| Electronics manufacturing |

Compliance (other): - Human rights expectations, including International Labour Organization (ILO) and national labour laws - Anti-corruption - Trade sanctions Supply chain management: - Material Declaration Management Standard |

| Mining and metals |

AML compliance: - General AML regulations - Industry-specific AML regulations, such as for Belgian diamond traders) Compliance (other): - Bribery - Foreign Corrupt Practices Act - Modern Slavery Act - Human rights expectations, such as under the United Nations Guiding Principles and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises Voluntary: - Industry good practices |

Processes and departments in which beneficial ownership data is used

For many of the surveyed companies, the data was ingested and overseen by compliance departments, even if it was also used elsewhere in the company for purposes other than compliance. This was particularly relevant for commercial banking, where compliance is the biggest driver for the use of BO data. A majority of respondents from electronics manufacturing and from mining and metals companies reported knowing which other departments or teams in the company used BO data. A minority reported that each department obtained the data themselves, rather than ingesting it centrally.

| Industry | Departments or teams cited in survey responses |

|---|---|

| Commercial banking |

‐ Compliance/legal/AML ‐ KYC team - First line of defence - Customer due diligence (CDD) ‐ Financial crime compliance ‐ Surveillance ‐ Investigations ‐ Sustainability |

| Electronics manufacturing |

- Supply chain - Compliance - Risk/operational risk - Sustainability |

| Mining and metals |

- Community and social responsibility - Legal, compliance - Human rights - Risk/credit risk - Supply and procurement - Ethics |

Importance of beneficial ownership data in different business processes

Compliance with regulations was seen as the most important use of BO data for jurisdictions where regulations existed because of possible sanctions or fines and reputational risks. For each of the three industries, respondents covered multiple jurisdictions and regulations. Which use cases were considered the most important depended on the industry and specific regulations.

For commercial banking, KYC obligations and transaction monitoring were considered the most important business processes for which BO data is used. For electronics manufacturing and mining and metals, complying with legislation such as the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the UK Bribery Act, and with AML regulations was considered relevant. This wider range of applicable regulations is likely to be found in other real sector industries as well, such as textiles, footwear, and other types of manufacturing, due to the international nature of their supply chains, including in jurisdictions where corruption and bribery are perceived to be more prevalent.

Other business processes and decisions – such as supply chain management, implementation of sustainability strategies, and procurement – also use BO data. Most often in these situations, BO data is one of a number of data points needed to gain the required insights.

| Industry | How important is BO data to each of the following business processes? |

|---|---|

| Commercial banking | |

| Due diligence of suppliers, vendors, and distributors | Not at all important |

| Client onboarding and KYC | Very important |

| Currency transaction reports and other transaction monitoring | Very important |

| Due diligence of other business partners | Important |

| Due diligence grantees/recipient entities of charitable giving/corporate social responsibility (CSR) | Not at all important; very important[6] |

| Human rights assessments (third parties) | Somewhat important (only conducted periodically) |

| Anti-corruption assessments or anti-corruption compliance processes (third parties) | Somewhat important (only conducted periodically) |

| Other (risk management, name screening) | Important |

| Electronics manufacturing | |

| Anti-corruption assessments or anti-corruption compliance processes (partners, suppliers, and third parties) | Very important |

| Due diligence of suppliers, other vendors | Very important |

| Due diligence of vendors | Not important |

| Due diligence of other business partners | Very important |

| Human rights assessments (partners, suppliers, and third parties) | Very important |

| Due diligence/selection of grantees | Not important; very important |

| Sustainability/ESG/CSR reporting | Not important; very important |

| Mining and metals | |

| Anti-corruption assessments or anti-corruption compliance processes (partners, suppliers, and third parties) | Important; very important |

| Due diligence of suppliers, other vendors | Important; very important |

| Due diligence of distributors | Important; very important |

| Due diligence of other business partners | Somewhat important; important; very important |

| Human rights assessments (partners, suppliers, and third parties) | Somewhat important; important; very important |

| Due diligence/selection of grantees | Important; very important |

| Sustainability/ESG/CSR reporting | Somewhat important; important |

| Other (credit assessments) | Important |

Importance of beneficial ownership data in certain markets

The three industries surveyed have different perceptions of the value of BO data in different markets. Respondents from electronics manufacturing and mining and metals responded that the use of BO data was more important in some markets than others, noting higher political risk in some jurisdictions as well as risks related to jurisdiction-specific difficulties in accessing and verifying BO data. Respondents from commercial banking, on the other hand, did not perceive any markets to be more important than others. This could relate to the more extensive regulations that apply to financial institutions, as well as their current use of BO data throughout the organisation.

| Industry |

Are there markets in which beneficial ownership data is more important? |

|---|---|

| Commercial banking | No |

| Electronics manufacturing |

Yes, beneficial ownership data is more important in: - Politically high risk markets - Markets in which data is harder to validate outside of the UK and the US |

| Mining and metals |

Yes, beneficial ownership data is more important in: - High risk jurisdictions - High risk transactions taking place in high risk markets - Small scale or local suppliers |

Length and frequency of use of beneficial ownership data

Across each of the three industries, the use of BO data is not new.[7] Only in mining and metals did one respondent note that they had commenced using BO data in the past one to three years. Survey respondents in the electronics manufacturing industry noted that whilst BO data had been used within the organisation for longer than three years, it was being used in new departments and in more business decisions in recent years. The frequency of use depended on the department responding to the survey, with the exception of commercial banking, which used BO data on an ongoing or daily basis across the board. Each industry had at least one department that used BO data on an ongoing or daily basis.

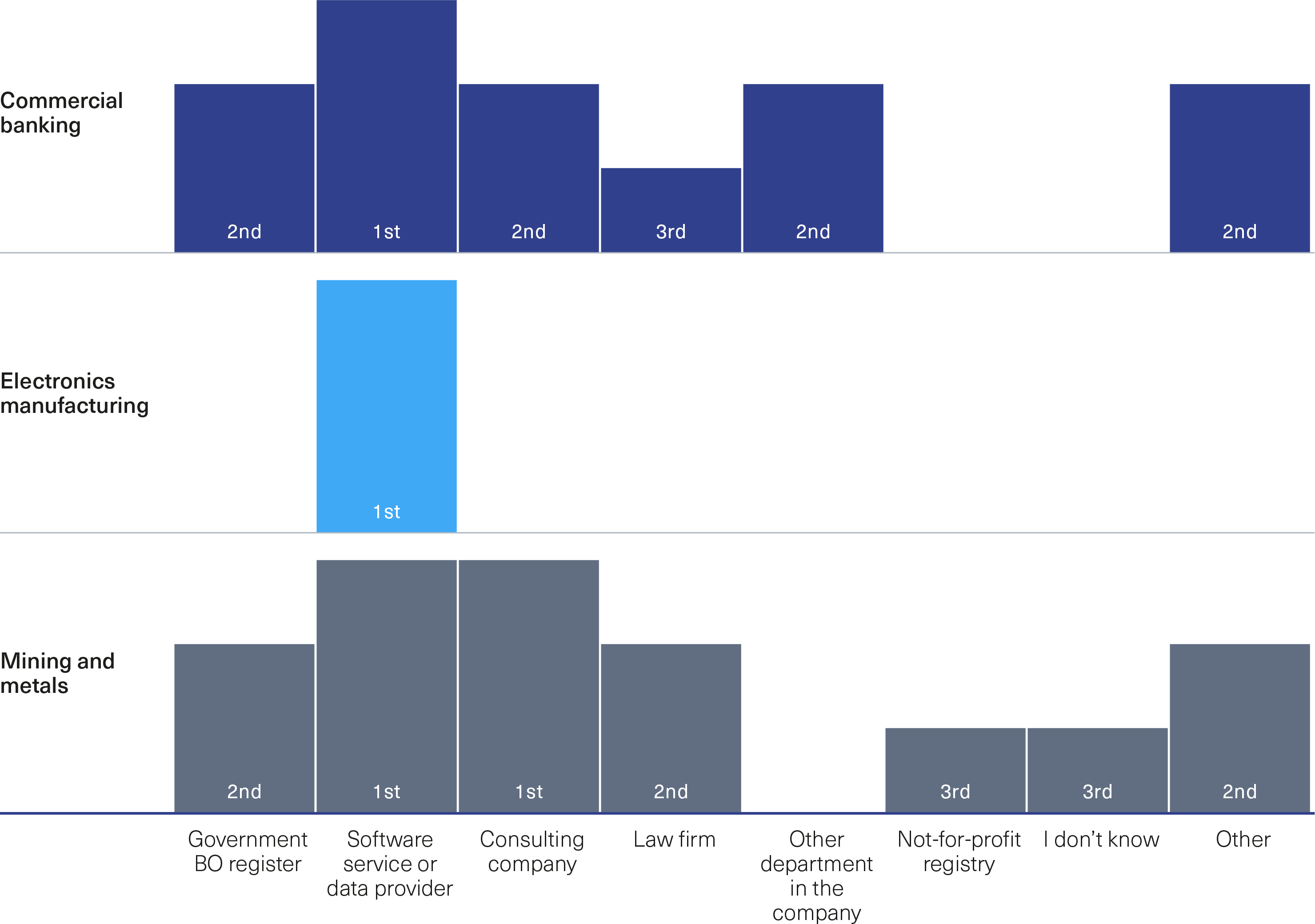

Beneficial ownership data sources

The providers of BO data varied by industry, but third party BO data providers were reported as the most common source. Many respondents combined different sources and formats. Mining and metals used the widest range of data providers and noted sourcing data directly from government registers, though third party BO data service providers were most frequently used. Respondents in electronics manufacturing only listed third party BO data service providers as a source.

Both commercial banking and mining and metals reported requesting and receiving data directly from companies they were dealing with. Commercial banking also reported “acceptable data sources which are websites deemed to be suitable for identification and verification purposes.”

Figure 6. Sources of beneficial ownership data

A higher use of government BO registers in mining and metals may be due to the introduction of a beneficial ownership transparency requirement in 2016 for countries implementing the EITI Standard. Requirement 2.5 requires that “implementing countries request, and companies publicly disclose, beneficial ownership information,” and recommends “that implementing countries maintain a publicly available register of the beneficial owners of the corporate entity(ies) that apply for or hold a participating interest in an exploration or production oil, gas or mining licence or contract.”[8]

The issue of liability is a potential disincentive against companies’ use of government BO registers. As one BO data service provider expressed, there are limits to how public BO registers are used in meeting compliance obligations: “If publicly available data has been used and the client has been diligent in following compliance standards, what happens if [it turns out that the data was wrong and] that one of their [clients appears] on a sanctions list? There are limits to their responsibility and liability based on the data they had access to.”[9]

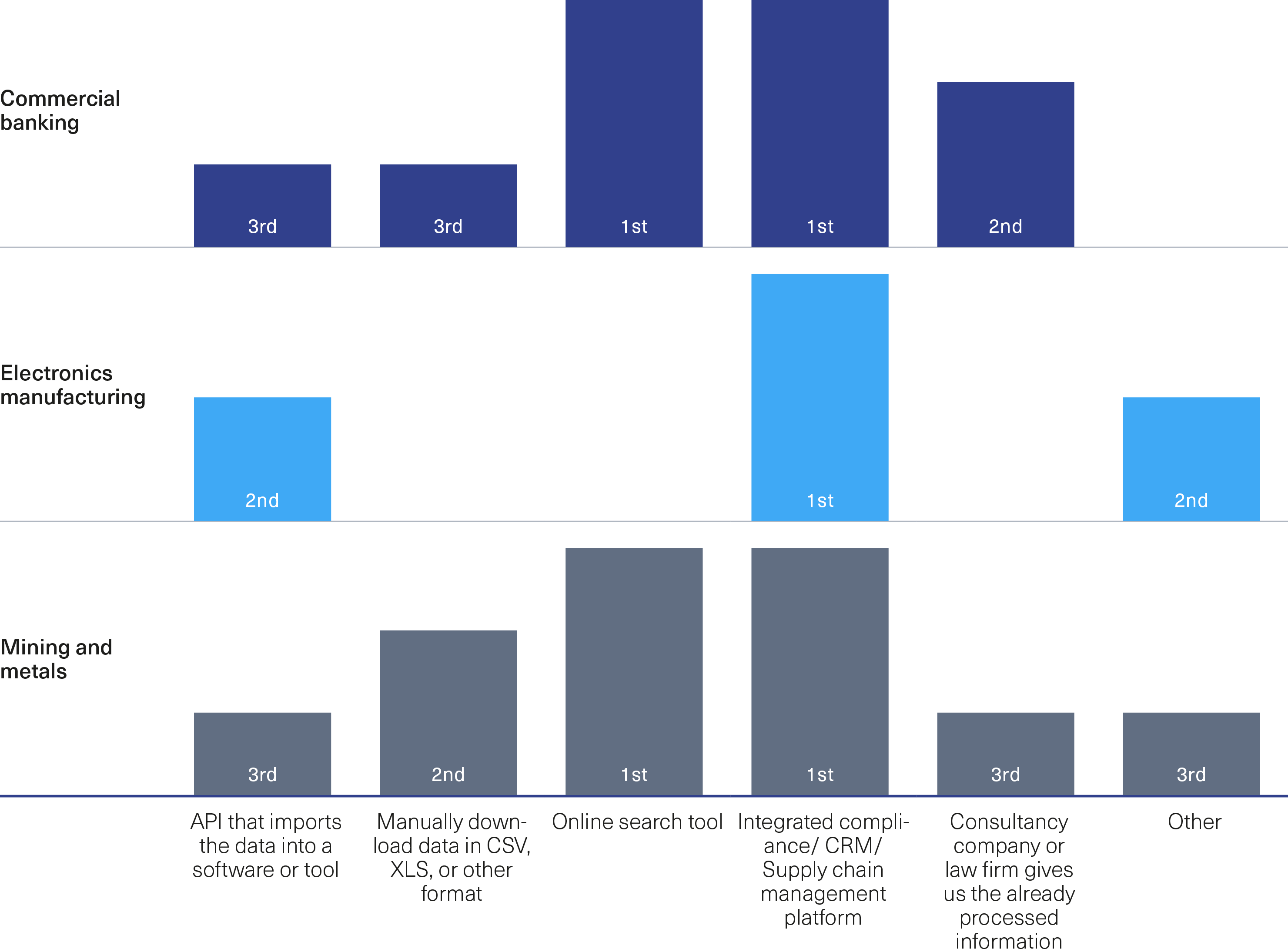

Beneficial ownership data format

The surveyed industries receive the data in a range of formats.

Figure 7. Beneficial ownership data format

With the exception of some mining and metals respondents, the majority of respondents said that BO data was combined with other datasets specific to different business processes. For these purposes, BO data is more useful if it is available as machine-readable and interoperable structured data, as this makes it easier to combine with other datasets. This need was also raised when discussing challenges in using BO data, as discussed below.

Beneficial ownership data points

Which specific BO data points were considered most important varied by industry, and depended on the business processes the data was used in, along with companies’ jurisdiction and risk profile. The most commonly cited were name and date of birth. Some considered beneficial owners’ addresses and countries of residence to be valuable. Nationality was also considered important by some. Several respondents noted that the individual data points were not as important as whether the combined data points would be sufficient to be able to “identify ultimate owners, hiding behind various company fronts.”[10] A respondent from commercial banking noted: “All of those [fields] are equally important – what does matter is being able to verify the customer or recipient through the data available.”[11] For data to be useful, it is necessary that sufficient detail is collected and presented to unambiguously identify individuals, although different minimum combinations of data points are required to do this in different jurisdictions.

Another respondent noted the importance of historical data in providing the insights they required. Historical records can help verify accuracy of more than the data provided, as it offers insights into name and other changes made, which can otherwise be used to obscure BO.[12]

Beneficial ownership data availability

When asked if the respondents were able to consistently access the data fields that they required, all respondents from electronics manufacturing and the mining and metals sector responded: “Not for all markets”. More respondents from the commercial banking sector replied “Yes, most often”, but some respondents chose both options. As covered later on, data being unavailable is a challenge for all industries, and the most common challenge reported by commercial banks.

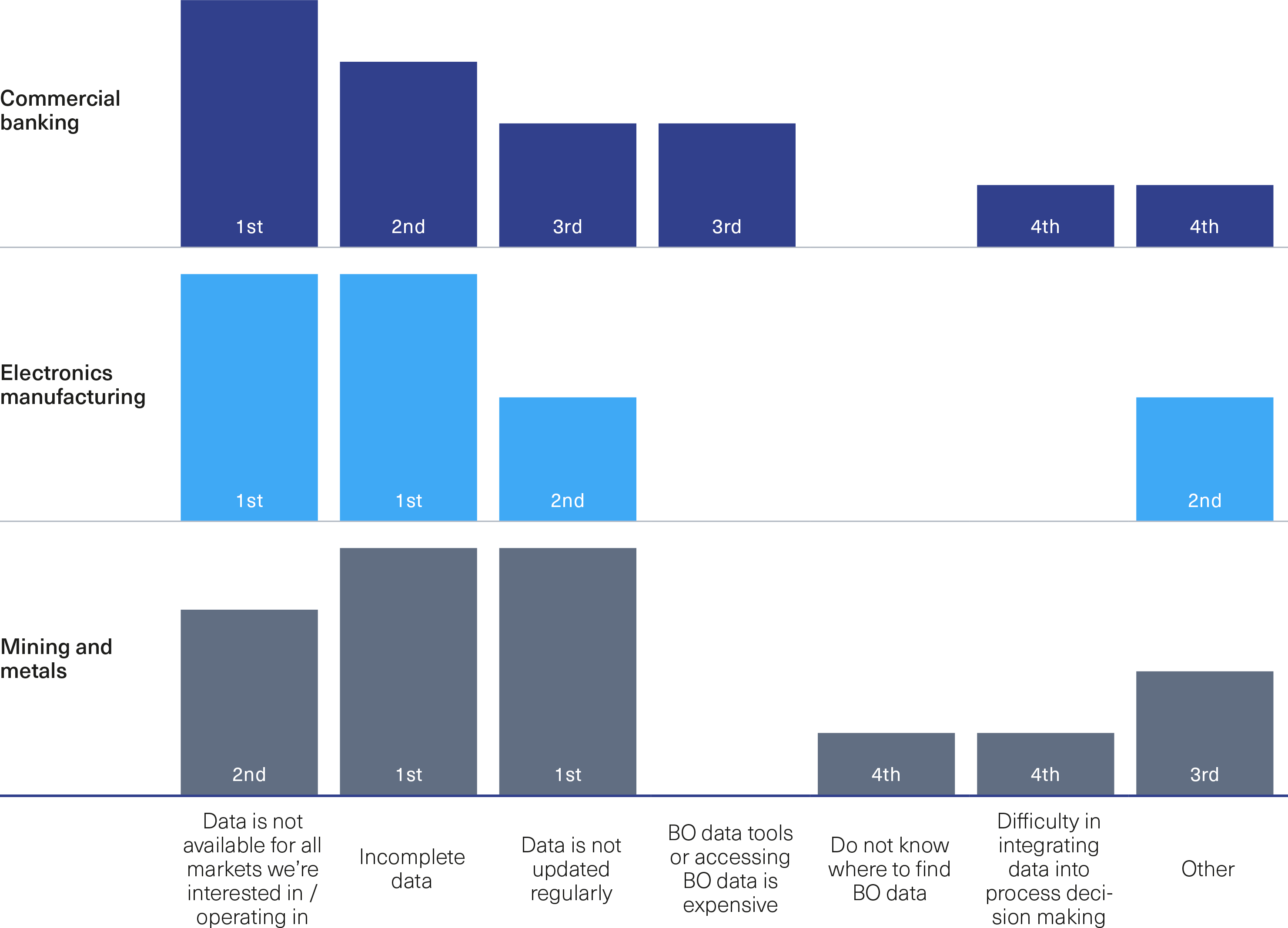

Challenges in the use of beneficial ownership data

Group 2 respondents experienced a range of challenges with their use of BO data. Because of the lack of reliability and gaps in the data, survey respondents from all three industries noted that they needed to verify the data they obtained, whether the data was provided through software, from company registers, or directly from the companies themselves. One respondent from the mining and metals sector noted: “No single source [of BO data] is relied on. We always use other internal and external information as appropriate.”[13] Companies verified BO data using information obtained through other registers, social media, company reports, and by requesting information directly from the entity in question.

Figure 8. Challenges with beneficial ownership data

Verification was particularly an issue for commercial banking institutions, who need to verify data to the best of their ability under AML regulations. A respondent from commercial banking noted: “We have to use multiple sources and cross reference the data to see which is most up to date and accurate. This is a manual process that takes a lot of time.”[14] This response should be seen in the context of the significant and rising cost of compliance.[15] Other respondents across the three industries noted that they obtain information directly from the counterpart entity in question. Again, this is a manual and highly time consuming process. This suggests that improving the availability, accuracy, and reliability of the base level of data ingested may help reduce compliance costs, even where best-effort verification requirements for AML/CFT regulated entities remain in place.

Current challenges to using BO data can in part be addressed through technical approaches. For instance, data science techniques can facilitate the supplementing and cross-referencing of BO data with data from other sources. Technical approaches can also help companies make procurement decisions to obtain the latest BO data products and services from the best vendors. This means employing a short procurement cycle and regular fit-for-purpose assessments of products. Whilst this may address some issues, these solutions may not be available to all companies due to cost, and do not address the challenge of “garbage in, garbage out” (the concept that flawed inputs produce flawed outputs).

When requesting information directly, respondents from metals and mining noted that they encounter a lack of willingness among companies to disclose their BO: “Often private companies are unwilling to share information.”[16] The time delay in using and verifying BO data was also noted as an impediment: “We need the data for business decisions but it may take time to get hold of the data, and verify it.”[17] Another respondent noted that varying standards of data collection constrained data use and often required manual interpretation.

The risk-based approach is a common and growing practice in compliance. It means that entities themselves will decide when a situation (e.g. a specific transaction, vendor, market, etc.) presents a higher risk and will prioritise and allocate resources accordingly towards the due diligence or monitoring. This approach – whilst ostensibly allowing resources to be dedicated towards higher risk – is based on a company-centric understanding of risk, which may not always place the intent of regulations at the centre of understanding.[18] In short, companies may dedicate fewer resources in jurisdictions where they know that regulations or enforcement are weak, and where the risks of noncompliance are low, highlighting the need for the availability of reliable data.

As one respondent pointed out: “We use a risk based approach, depending on the scope and scale of the proposed activity and risk profile of the jurisdiction or political environment.”[19] With regards to challenges that BO data presents, the degree of supplementing or cross-referencing is commensurate with a determination of the degree of risk present. These approaches vary in sophistication. As another respondent explained in reference to whether to use other data to supplement BO data: “If the beneficial owner is not on a PEP or sanctions list, we may leave it there.”[20]

Lack of interoperability was reported as another significant challenge. Often BO data is stored in a particular system or database structure, and it is not automatically able to exchange information with or relate to other data sets, for instance, in order to verify BO data. Combining BO data with other data sets often involves manual work or paying a third party, and is not always possible. As one respondent noted: “Each time [the customer] wants to add or wants to use a new data point, we have to see if it will work with the dating and structuring of the existing data.”[21]

The insights from BO data itself were also seen to be fairly limited outside of compliance requirements. Risk departments noted that the ways in which most BO data service providers’ tools offer the information makes it difficult to gain the kind of aggregated view of legal entities that would be needed to see complete ownership structures. Respondents acknowledged that BO may be held indirectly through multiple legal entities, and there is not always sufficient information to understand full ownership chains. One respondent from the commercial banking sector noted that, ideally, BO data should help elucidate the owner’s “relationships with other entities and with other named individuals.”[22] This highlights the potential value of widespread global disclosure of BO data as structured data according to a minimum standard to ensure interoperability.

Group 3 entities: Investors and environmental, social, and governance stakeholders

The third group of private entities identified covers a large range of stakeholders who have an interest in BO disclosure. Institutional investors – such as pension funds, mutual funds, sovereign wealth funds, and insurance companies – invest on behalf of clients, members, or customers. Though many are passive funds, due to the volume of their investments, they can shape the face of business and practices of individual companies through their investments. There is growing pressure for institutional investors to use BO data in due diligence – both in terms of identifying investable companies and as a part of risk identification and management, which can be more important in markets where a lack of regulations means certain standards are absent.

Companies listed on stock exchanges and their (potential) investors are other stakeholders within group 3 that have interest in the use of BO data. This is important not only from an AML/CFT perspective, but also because of the growing practice of shareholder activism, as shareholding beneficial owners use equity stakes in listed companies to put pressure on management. In some cases majority shareholders may also do this for personal gain, at the expense of minority shareholders.

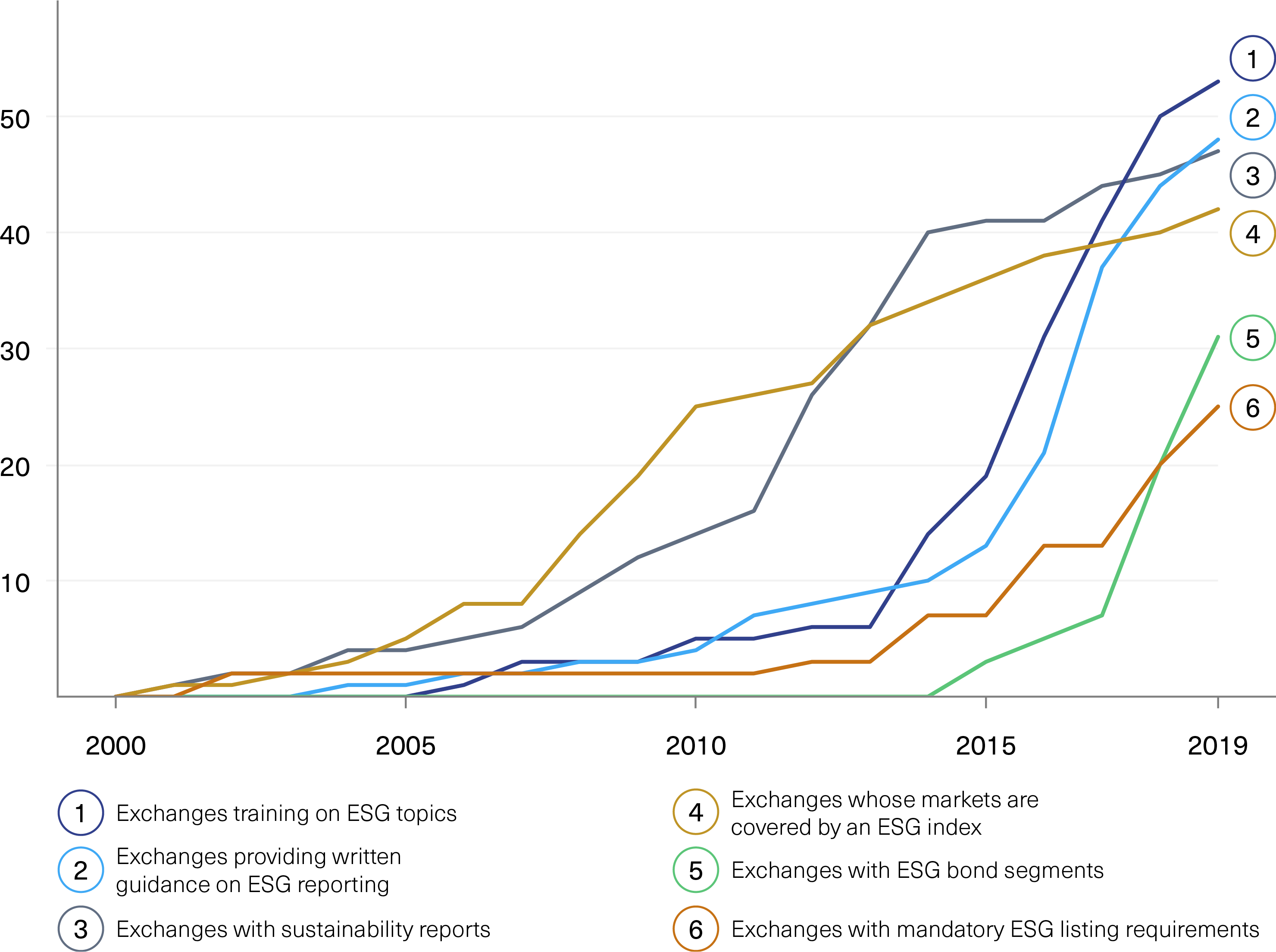

Entities involved in the advocacy, promulgation, and service provision of sustainability frameworks that draw on ESG standards for private companies are also BO data users. They may be private, not-for-profit, non-governmental, or intergovernmental organisations. With the growth in sustainability frameworks and in interest from investors and regulators in reporting on sustainability, these entities will play an increasingly important role in the uptake of voluntary codes and regulations related to sustainable business practices, and, within those, on the use of BO data. This includes entities such as the Sustainable Stock Exchanges (SSE) Initiative, the Global Reporting Initiative, the Sustainable Accounting Standards Board (SASB), Integrated Reporting, the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI),[23] and even a number of private investment funds and development finance institutions at the forefront of pushing for sustainable business, such as BlackRock and the CDC Group.

There is also a cadre of service providers that offer consulting services to assist companies in environmental and social risk management, and in developing systems for compliance with ESG reporting requirements. They are often also users of BO data on behalf of their clients. Institutional investors hold similar motivations for BO disclosure in portfolio companies. A recent United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) report confirmed the growing trend of the integration of ESG requirements and reporting into investment practices (see Figure 9).[24]

Figure 9. Stock exchange trends

Adapted from: UNCTAD[25]

With the growing number of reports of the inflation of ESG ratings,[26] guaranteeing high quality data and expanding the types of data available may be of increasing importance. In a conversation with experts on ESG reporting, several noted that the relative ease of defining and measuring key performance indicators for environmental standards has led to an overemphasis on this domain, while governance metrics remain lacking. There is potential for BO information and standards to help bridge this gap. WEF has also advocated for a holistic approach to risk and compliance, stating that mainstreaming integrity in business practices is “indispensable to achieving a sustainable future,” and citing BOT as a potential way to enhance compliance.[27]

Other industry-specific standards also exist, developed and certified by professional bodies and other international bodies, such as the ISO,[28] which could drive the use of BO data. Whilst voluntary, companies in certain industries seek ISO certifications for global operations. The certification assures business partners, customers, and even end consumers that products and services have been made to international quality standards.

Challenges in the use of beneficial ownership data for environmental, social and governance reporting

As in groups 1 and 2, group 3 data users also face challenges in verifying the data they use. Additionally, they reported challenges regarding the ways in which data can be used for insights. The ESG regulators, and investors in particular, pointed to knowledge gaps they are currently left with when using BO data. These included difficulties in deriving deeper insights. “[We] may want to know more about a particular owner and other companies, which can provide better insights into what can be expected on the ES and especially G perspectives of the company that we’re looking to invest in.”[29] Others noted that the BO data currently available to them may provide a starting point, but they would need to conduct a full audit trail by piecing together information including company ownership.

When asked how companies work around these challenges, responses varied from simply making do (“we live with it as it is”[30]) to technical and strategic ways of dealing with the challenges. Most respondents reported employing technical solutions to data availability challenges, such as supplementing data and cross-referencing with additional sources.

How companies see the use of beneficial ownership data developing in the future

The following section summarises the survey responses to questions covering how respondents foresee BO data use in the future, as well as secondary research undertaken on the topics identified.

Growing importance of beneficial ownership data

The majority of respondents replied that they anticipated BO data would become more useful and important, with less than a quarter responding that it would stay as useful and important as it currently is. Much of this sentiment is due to the regulatory momentum and the significant reputational and financial risk of failing to comply with new, stricter regulations.

There are also industries that are not currently covered by regulations mandating the use of BO data, which may well see the development of government oversight, such as financial securities. Whilst AML regulations do apply to many FinTech companies and non-banking financial institutions, e-payments, peer-to-peer (P2P) tools, and e-wallets,[31] there is likely to be very strong growth in the number of users of and the volume of transactions through these entities. Recent surveillance has identified a large amount of money laundering and fraud being conducted through the use of applications for transfers.[32]

Part of the growth in the use of these apps will come from continued growth in e-commerce, which relies on them for payment for goods and services over the internet and in the provision of novel P2P services. In addition to the financial transactions which fall under AML regulations, many e-commerce platforms typically offer third party goods or services provided by companies that span the globe. At this time, the degree of due diligence conducted by e-commerce platforms on their third party providers is unclear, and needs further research.

Verification

Private entities will continue to use technology to verify BO data offered by government registers with additional data sources, such as scraping social media, particularly where there may be significant gaps in register data.[33] At the same time, this is likely to present barriers for smaller entities who may not not have the resources for these new technologies.

The continuing development of new technologies and the recent challenges of working in the COVID-19 pandemic have contributed to continuing transformation of verification practices, which must become fit for purpose in increasingly digital economies. For example, banks have recognised the need to conduct remote onboarding and KYC because of pandemic response measures.[34] Technological advances offer great potential to move beyond systems that are dependent on physical records to a modern digital economy that uses the scores of attributes that are created by individuals on a regular basis to verify identities.

Improvement of identity verification (IDV) controls used in KYC is already taking place, and its application by financial institutions will also assist in the verification of BO data. One opportunity, which must be carefully balanced with data privacy and data protection needs, is the expansion of digital IDV from single to multiple attributes or points of verification that comprise an identity network. These digital identity networks will make it easier to cross-reference and verify BO data.[35]

Value-add by data service providers

BO data service providers are offering increasingly sophisticated tools that can add even greater value to BO data. In addition to providing access to register data and conducting volume searches and ways of verifying data, greater customisation of offerings for specific types of users within the private sector can be seen outside of the primary regulatory uses, such as for investors, or for sustainability departments who wish to better understand the relationships of beneficial owners to other entities and individuals on PEP and sanctions lists. Helping mitigate reputational risk was cited as a strong driver in this regard.

Whilst the number of BO data service providers – especially newer, smaller providers who are challenging larger and more established providers – has grown in recent times, there are some signs that this growth may slow as initial investor enthusiasm starts to wane.[36] Some industry experts have suggested that regulated entities lack incentives to spend increasing amounts of money on better data that makes use of more expensive technology.[37]

Mitigating risks in global supply chains

For companies moving to more global supply chains or expanding into new markets, risk management is increasingly being incorporated into business strategy. This trend has been amplified by economic and supply chain challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The imperative to properly identify risks associated with partners, vendors, suppliers, and other third parties is growing.

A risk-based approach – as many of the survey respondents pointed out – means having a good understanding of the environment and of each entity a company is working with as a client, supplier, joint venture partner, and so on. Knowing who controls those companies is a key part of that understanding, and becomes more important in the context of new and fast-changing supply chains. As one respondent from electronics manufacturing noted, “Differences in data from different markets is part of our risk assessment process. If we feel we are not able to get complete info on a supplier from a particular market and there are questions, we may well select suppliers from other markets with better information, if all other factors are equal.[17] ”[38] This supports the view that BOT can improve the business environment and attract investment, which has been a key driver for reforms for some governments.

Environmental, social, and governance indicators and economic performance

Another trend that has been given further impetus during the COVID-19 pandemic is the degree to which investors, whether asset managers or owners, see ESG indicators as key to weathering crises and to medium-term business performance. Whilst the trend has been increasingly important, some had feared that these would merely be “nice to have” for investors during the pandemic and other crises. Instead, we see that the complex risks posed by the pandemic have actually encouraged record capital allocations towards investments, to which ESG performance is central.[39]

Complex risks have encouraged investors to look far more closely at a company’s ability to manage crises with adaptation and resilience, for instance through robust governance and effective leadership. As mentioned, investors are increasingly taking a deeper look into the governance track records of the controllers and owners of companies in which they are interested. This includes evaluating the steps that companies are taking to uncover beneficial owners of companies within their supply chains as an important indicator of how these companies manage risk. These trends are converging and driving an approach towards business integrity and ethics that is central to companies’ business models. Transparency in who owns and controls companies is a key part of this.

Notes

[1] Deloitte, “Impact Assessment study on the list of High Value Datasets to be made available by the Member States under the Open Data Directive”, European Commission, 7 January 2021, 112-118.

[2] Transparency International, “Access Denied? Availability and accessibility of beneficial ownership data in the European Union”, May 2021.

[3] Respondent, BO data service provider, October-December 2020.

[4] World Economic Forum, “Partners”, n.d., https://www.weforum.org/partners.

[5] World Economic Forum, “The Rise and Role of the Chief Integrity Officer: Leadership Imperatives in an ESG-Driven World”, White Paper, December 2021, 18, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Rise_and_Role_of_the_Chief_Integrity_Officer_2021.pdf.

[6] Half of the respondents noted “Not at all important” and half “Very important”. As all the commercial banks included in the survey had CSR departments that engaged in grant-giving, the responses likely denote different risk perceptions with regard to the recipient entities.

[7] As the research focused on uncovering new uses of BO data, “For longer than three years” was the longest option in the survey. BO data has been used for far longer than three years for many industries.

[8] “Beneficial ownership: Who are the real owners of companies?”, EITI, n.d., https://eiti.org/beneficial-ownership

[9] Respondent, BO data service provider, October-December 2020.

[10] General Manager, Social Performance Department, mining and metals company, September-December 2020.

[11] Manager, Legal and Compliance Team, commercial banking company, September-December 2020.

[12] Respondent, mining and metals company, September-December 2020.

[13] Respondent, mining and metals company, September-December 2020.

[14] Respondent, commercial banking company, September-December 2020.

[15] See, for instance: “Global True Cost of Compliance 2020”, LexisNexis, June 2021, https://risk.lexisnexis.com/global/en/insights-resources/research/true-cost-of-financial-crime-compliance-study-global-report.

[16] Respondent, mining and metals company, September-December 2020.

[17] Respondent, mining and metals company, September-December 2020.

[18] Risk assessments used in risk-based approaches usually consider the company’s internal processes and systems strengths and weaknesses, the regulatory environment as well as the nature of the transaction or potential partner. See, for example: Financial Action Task Force, “Guidance for a Risk-Based Approach”, October 2014, 8-11, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Risk-Based-Approach-Banking-Sector.pdf.

[19] Respondent, September 2020-January 2021.

[20] Respondent, September 2020-January 2021.

[21] Respondent, BO data service provider, October-December 2020.

[22] Respondent, commercial banking company, September-December 2020.

[23] See Sustainable Stock Exchanges Initiative at www.sseinitiative.org, Global Reporting Initiative at www.globalreporting.org, SASB at www.sasb.org, Integrated Reporting at www.integratedreporting.org and the UNPRI at www.unpri.org.

[24] UNCTAD, “World Investment Report 2020: International Production Beyond the Pandemic”, United Nations, 15 July 2020, 199, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/WIR2020_CH5.pdf.

[25] UNCTAD, “World Investment Report 2020”, 200.

[26] See, for instance: Leanne de Bassompierre, Saijel Kishan and Antony Sguazzin, “Palm oil giant’s industry-beating ESG score hides razed forests”, Moneyweb, 18 September 2021, https://www.moneyweb.co.za/news/international/palm-oil-giants-industry-beating-esg-score-hides-razed-forests/.

[27] Anna Tunkel, Katja Bechtel and Robin Hodes, “How we can support the evolving global integrity agenda”, World Economic Forum, 7 October 2021, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/10/how-to-support-the-evolving-global-integrity-agenda.

[28] The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is a non-governmental body that works with national standards boards to develop voluntary standards that help facilitate global trade. Some of the existing ISO standards (e.g. ISO 15022) include BO data.

[29] Respondent, ESG stakeholder, November 2020-January 2021.

[30] Respondent, ESG stakeholder, November 2020-January 2021.

[31] P2P applications include Cash App, Venmo, and Paypal and those offered to financial institutions, such as Zelle. E-wallets include Google Pay, Facebook Messenger, and Apple Pay.

[32] Transparency International, “Together in Electric Schemes”, December 2021, https://www.moneylaundering.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/TransparencyInternationalUK.Report.MLRisksEPayments.121421.pdf.

[33] See: What is next-generation AML?, SAS, November 2020, https://www.sas.com/en/whitepapers/next-generation-aml-110644.html

[34] Remote, digital ID verification is considered standard or even lower-risk by the FATF, see: Financial Action Task Force, “FATF Guidance on Digital Identity”, March 2020, http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Digital-ID-in-brief.pdf

[35] Ibid; “Picture Perfect: A blueprint for digital identity”, Deloitte, 2016, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/Financial-Services/gx-fsi-digital-identity-online.pdf

[36] Oliver Smith, “Exclusive: Data group DueDil to merge with Artesian Solutions after failing to raise funding”, AltFi, 6 August 2021, https://www.altfi.com/article/8192_exclusive-data-group-duedil-to-merge-with-artesian-solutions-after-failing-to-raise-funding

[37] Jane Jee, “The Future of Financial Crime: Voices from the Dark Money Conference”, fscom, November 2021, 8-9, https://f.hubspotusercontent30.net/hubfs/2934033/The%20Future%20of%20Financial%20Crime-%20Voices%20of%20the%20Dark%20Money%20Conference%202021%20Publication.pdf.

[38] Respondent, September 2020-January 2021.

[39] See: “Why COVID-19 Could Prove to be a Major Turning Point for ESG Investing”, J.P. Morgan, 1 July 2020, https://www.jpmorgan.com/insights/research/covid-19-esg-investing