What’s in it for business? The US case: Lessons from private sector and civil society advocacy for beneficial ownership transparency reforms

Context

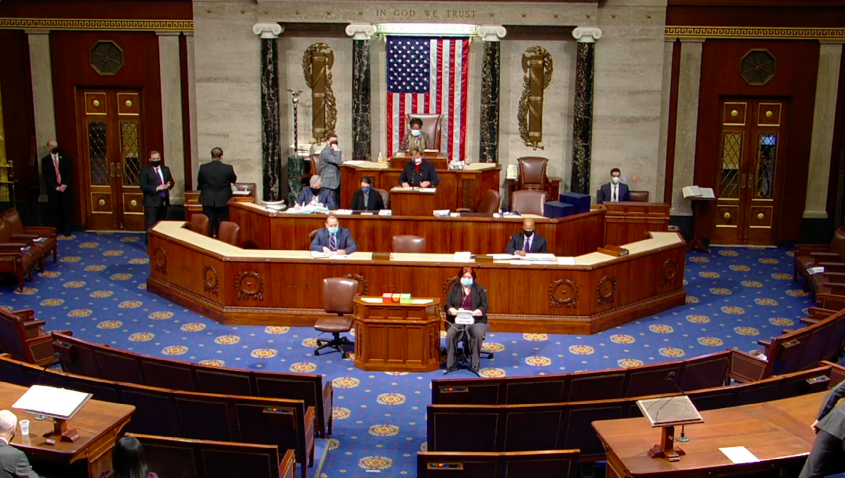

The US House of Representatives voting on the National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2021, which includes the Corporate Transparency Act. 28 December 2020. Credit: House.gov.

With its roots in AML policy, BOT has been connected to a growing number of policy areas, including anti-corruption, domestic resource mobilisation, and natural resource management. [7] Support for BOT from various actors and institutions has grown steadily since the launch of the first BO registers in 2015. For example, the European Union, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), the G7, the G20, the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations, the World Bank, extractive companies, [8] and many national and international civil society organisations and media professionals and bodies have all come out in support of BO reforms, although with diverging ideas and standards on what these reforms should look like.

The potential benefits of access to high-quality BO data for private sector entities, and of BOT for business more broadly, have been well established. [9] They include both levelling the playing field to broaden market participation and improve competition as well as allowing businesses to better manage risk. There is a growing trend in voluntary standards around the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance of companies, which is creating incentives to use BO data to gain better insights into suppliers, partners, and investees. Some countries, such as Latvia, are implementing BOT to create an enabling business environment and attract inward investment. [10] By March 2023, over 120 countries had committed to BOT in at least one sector of their economy. [11]

Despite growing global momentum, there is still a long way to go in terms of implementation. There is considerable divergence in how reforms are implemented, meaning, they do not always lead to useful and usable information that is accessible for data users, including private sector entities. In some places, both government implementers and potential private sector data users lack awareness and sensitisation on the potential benefits of BOT. Actors across civil society and, increasingly, the private sector have both an interest and a crucial role to play in ensuring that commitments are fulfilled and that effective BO reforms lead to accessible, high-quality information about the real owners of corporate vehicles. This case study explores the role of private sector actors and civil society in driving support for BOT reforms in the US as well as the potential benefits which were critical in eliciting support.

In the US, despite a push for increased transparency in beneficial ownership and some legislative progress aiming to achieve AML goals in the mid-2000s, certain business associations were opposed to proposed legislation. Whilst countries like the United Kingdom (UK) and Ukraine had already moved to establish central BO registers with public access by 2016, the lack of disclosure requirements to authorities at both the state and federal levels meant that the US remained an attractive place for criminals and corrupt individuals to hide their assets. [12]

The US went from the absence of specific BO legislation in the early 2000s to the development of several bills and eventual passage of the CTA as part of the 2020 Anti-Money Laundering Act. [13] In the years leading up to the passage of the CTA, a group of civil society organisations – including the Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency (FACT) Coalition, Global Financial Integrity, Global Witness, and Transparency International US – sought the backing for BOT reforms from US-based private sector actors in order to gain sufficient political support for the CTA’s passage. Some of these actors, who were initially bystanders to the reform process, became active supporters of BOT. This case study looks at this journey. It highlights why these private sector actors consider BOT to be in their interest, and their role in supporting the passage of foundational legislation in the US.

Based on the experience of civil society advocates who closely worked with private sector actors to push for legislative changes on beneficial ownership in the US, this case study illustrates the impact that private sector action has had on moving towards greater beneficial ownership transparency in the country. It holds useful lessons for why BOT is beneficial for private sector actors, and more broadly for those who wish to lead the way in other countries, to build alliances with peers and ensure business interests can support and benefit from BOT reforms. It also includes useful lessons for international and national civil society organisations looking to engage the private sector to promote BOT reforms.

Notes

[7] Tymon Kiepe, “Corruption and Beneficial Ownership,” in Handbook of Public Procurement Corruption, eds. Sope Williams-Elegbe and Jessica Tillipman (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, forthcoming).

[8] Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), Statement by companies on beneficial ownership transparency (Oslo:EITI, 2021), https://eiti.org/documents/statement-companies-beneficial-ownership-transparency.

[9] See, for example: Sadaf Lakhani, The use of beneficial ownership data by private entities (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2022), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/the-use-of-beneficial-ownership-data-by-private-entities/; The B Team, Ownership is Everyone’s Business—Private Sector Action on Company Ownership (s.l.: The B Team, 2018), https://bteam.org/assets/reports/Ownership-is-Everyones-Business.pdf; World Economic Forum, The Rise and Role of the Chief Integrity Officer: Leadership Imperatives in an ESG-Driven World (Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2021), https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Rise_and_Role_of_the_Chief_Integrity_Officer_2021.pdf.

[10] “Latvijā arī turpmāk informācija par patiesajiem labuma guvējiem būs publiski pieejama”, Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Latvia, 6 April 2023, https://www.tm.gov.lv/lv/jaunums/latvija-ari-turpmak-informacija-par-patiesajiem-labuma-guvejiem-bus-publiski-pieejama.

[11] “The Open Ownership map: Worldwide commitments and action”, Open Ownership, n.d., https://www.openownership.org/en/map/.

[12] Lakshmi Kumar and Julia Yansura, The Future of Beneficial Ownership in the United States: Trade, Transportation, and National Security Implications (s.l.: Global Financial Integrity, 2020), https://financialtransparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Policy-Insight-BO-GFI.pdf.

[13] Kumar and Yansura, The Future of Beneficial Ownership in the United States; France Beard Johnson, David C. Rybicki, W. H. Snyder, and Michael M. Storm, “What Emerging Growth Companies and Investors Need to Know About the Corporate Transparency Act”, K & L Gates, The National Law Review 12, no. 220 (August 2022), https://www.natlawreview.com/article/what-emerging-growth-companies-and-investors-need-to-know-about-corporate.

Next page: Beneficial ownership transparency in the United States