Designing sanctions and their enforcement for beneficial ownership disclosure

Overview

Having adequate sanctions in place, and enforcing them effectively, can drive up compliance with disclosure requirements and increase the accuracy and usability of beneficial ownership (BO) data, thereby complementing verification mechanisms. It can also make legal persons and legal arrangements less attractive for criminals to misuse for the purposes of money laundering, terrorist financing, tax evasion, corruption, and other financial crimes. Research and case studies in recent years have shown that although a legal obligation to disclose BO information is the most effective means of ensuring disclosure, it will prove to be ineffectual unless it is supported by a robust sanctions and enforcement regime.[a]

Both the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an international standard-setting body for anti-money laundering (AML) and combating the financing of terrorism (CFT), and the European Union’s fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD5) require countries to apply “effective, proportionate, and dissuasive” sanctions for noncompliance with BOT requirements.[1] Criterion 5.6 of the Immediate Outcome 5 of the 2013 FATF Methodology, which assesses the implementation of beneficial ownership transparency (BOT) requirements by countries, also requires the assessment of the extent to which “effective, proportionate, and dissuasive” sanctions are applied against persons who do not comply with the BO information requirements.[2]

Nonetheless, despite asking countries to implement “effective, proportionate, and dissuasive” sanctions and enforcement systems for breaches of the BOT provisions, neither the FATF standards nor the AMLD5 prescribe any specific measures that should be applied by countries. There is also limited guidance, research, and available literature on the topic, which makes it difficult for policy makers and implementers to clearly understand what amounts to “effective, proportionate, and dissuasive” sanctions, and how to ensure their enforcement in practice.

A 2019 joint study conducted by the FATF and the Egmont Group has highlighted the fact that the lack of effective, proportionate, and dissuasive sanctions is one of the most common challenges faced by countries implementing BOT.[3] It is difficult to measure the effectiveness of sanctions, as it is challenging to establish direct causal effects between sanctions and compliance rates due to the presence of many other variables, such as a general compliance culture. Whilst high reporting rates cannot be attributable to sanctions alone, high rates have been associated with effective sanctions by the FATF, and the importance of sanctions to compliance is a core premise of this briefing.

This policy briefing aims to highlight some key considerations for policy makers and implementers in putting in place an effective sanctions and enforcement regime for BOT, identifying emerging good practice from different countries and outlining key policy principles. Whilst the briefing has aimed to include a geographical spread of country examples, many of the case studies focus on Western countries, as these tend to be the early-adopters of BOT reforms with the most information published on sanctions and their enforcement. The briefing aims to help policymakers and those implementing BOT reforms to think through various legal, policy and technical aspects of establishing effective sanctions regimes for ensuring BOT. It also briefly analyses some additional aspects that the BO sanction regime can cover – for example, preventing the misuse of data – and the recent developments in a few countries in this regard, although this is not the main focus of this briefing.[4]

To ensure sanctions regimes are comprehensive and do not contain loopholes, they should contain:

- sanctions against all types of compliance violations, including:

- non-submission of BO information;

- late submission;

- incomplete submission;

- Incorrect or false submission; and

- persistent noncompliance;

- monetary fines that are set sufficiently high, so they are not regarded as the cost of doing business for noncompliance with their BO disclosure requirements;

- non-financial sanctions – which may prove more effective than monetary fines – and criminal sanctions against both natural persons and legal entities (see Table 1);

- sanctions covering all the persons involved in declarations and key persons of the company, and the company itself. This includes the:

- beneficial owner(s);

- declaring person;

- company officers; and the

- legal entity.

This ensures that offending actors cannot claim plausible deniability or transfer liability to a single actor, and widens the pool of actors that have an interest in ensuring compliance maximising deterrence. If a country has imposed BO-related obligations (such as disclosure or a responsibility to ensure disclosures are accurate) on third parties (such as notaries or lawyers), these should also be made subject to sanctions for noncompliance or breach of their obligations.

The following features were identified in various disclosure systems as having a strong potential to contribute to effectively operationalising sanctions and their enforcement:

- clearly determining the authority that would be responsible to enforce sanctions and ensure that the designated authority has sufficient resources, legal mandate, and powers to enforce sanctions, including carrying out investigative or law enforcement functions;

- establishing proper procedures and processes to ensure the effective exchange of information between the agencies responsible for enforcement, for instance, between the registrar and prosecution authorities;

- ensuring they have the necessary jurisdiction over the legal person supplying information about non-domestic entities and beneficial owners, for instance, by creating a requirement for a domestic legal person to be involved in disclosure;

- publishing information about noncompliance and making information on sanctions imposed available to the public to drive up compliance by companies;

- automating sanctions mechanisms where possible;

- establishing a robust verification system to be able to better detect the submission of false information;

- reversing the burden of proof for administrative or civil fines and sanctions.

Establishing an effective, proportionate, dissuasive, and enforceable sanctions regime for noncompliance with BO disclosure requirements is a core tenet of the Open Ownership Principles (OO Principles).[5] The OO Principles set the standard for effective BO disclosure and establish approaches for publishing up-to-date and auditable data [6], for which proportionate and dissuasive sanctions and their effective enforcement play a critical role in ensuring compliance and enhancing the quality of data. The OO Principles make published data usable, accurate, and interoperable.

Table 1. Examples of sanctions according to types and targets

| Types of sanctions | Target: Beneficial owner(s) | Target: Declaring person | Target: Legal entities | Target: Company officers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial |

– Administrative or civil fine – Increasing fines for persistent noncompliance |

– Administrative or civil fine – Increasing fines for persistent noncompliance |

– Administrative or civil fine as a percentage of turnover – Increasing fines for persistent noncompliance |

– Administrative or civil fine – Increasing fines for persistent noncompliance |

| Non-financial |

Restrictions on: - voting rights; - shares, including suspending payment of dividends; - board appointment rights; - incorporating new companies |

- Revocation of professional or business licence (e.g., in case of notaries, lawyers, accountants, tax advisors, etc.) - Ban on being a declaring or authorised person for legal entities |

- Compulsory dissolution, deactivation, or striking off the company from the commercial register - Termination of business relationship by financial institutions (FIs) and designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs) - Ban on profit distribution and payment of dividends - Denial to grant or renew licence - Revocation or termination of licence or concession - Termination of any existing government contracts - Ban on supplying government contracts - Declaring a company dormant or inactive |

- Ban or disqualification from taking part in the management of any legal entity - Disqualification from the practice of business activities |

| Criminal | - Criminal fines and imprisonment for severe violations, e.g. knowingly false submissions to the legal entity | - Criminal fines and imprisonment for severe violations, e.g. knowingly false submissions to the register | - Criminal fines | - Criminal fines and imprisonment for severe violations, e.g. knowledge of a false submission to the register |

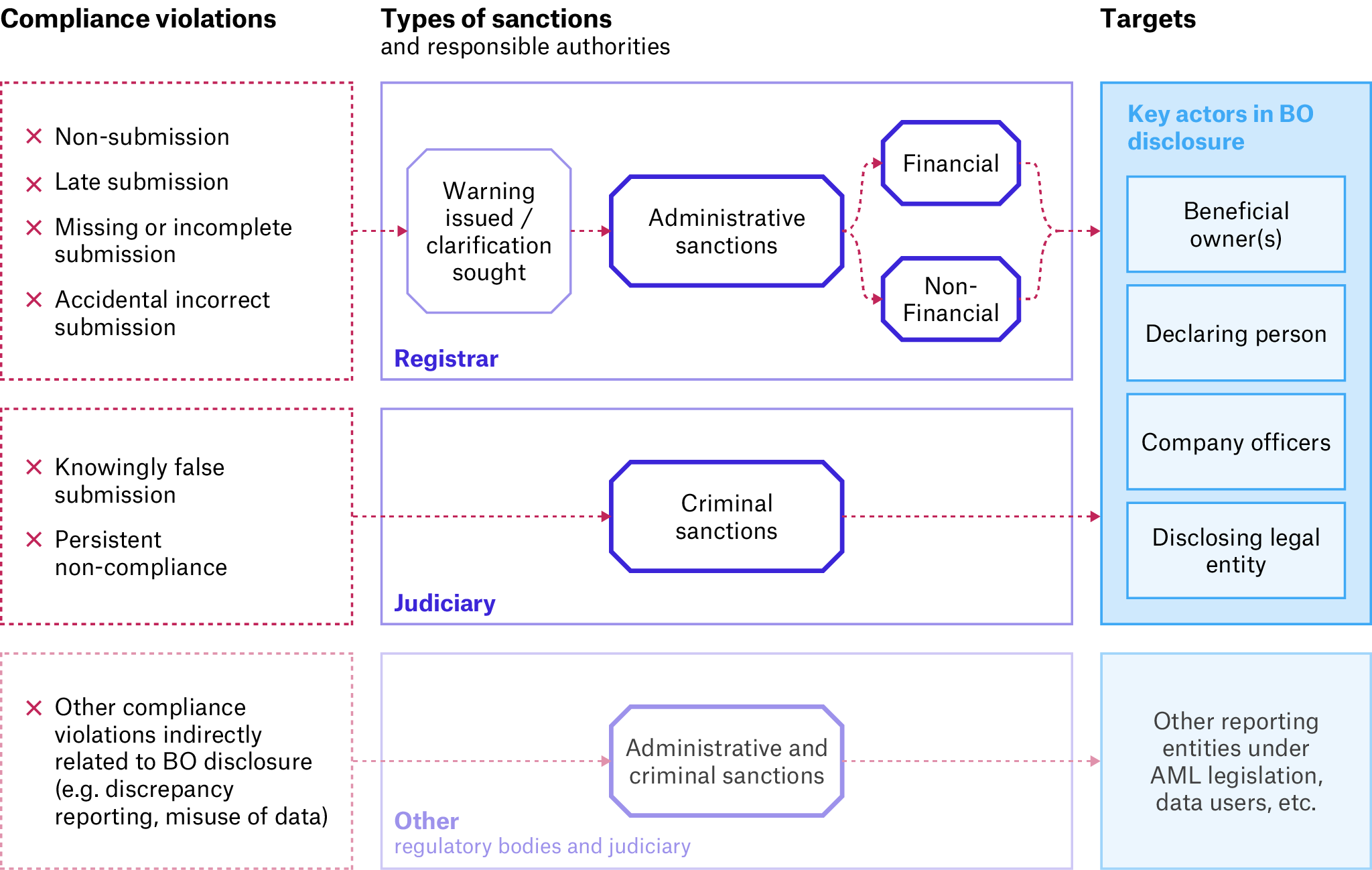

Figure 1. Example of a beneficial ownership transparency sanctions and enforcement regime

Sanctions regimes should cover all types of compliance violations, and have administrative financial and non-financial, as well as criminal sanctions for different violations, depending on severity and intent. Sanctions may also cover the noncompliance of other obligations related to disclosure. Sanctions should cover all the key persons and entities involved in declarations. Implementers should ensure sanctions are effective, and enforced, for instance, by clearly assigning roles, mandates, and powers to different authorities.

Foot note

[a] For example, countries implementing the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) Standard that have introduced voluntary disclosure regimes have experienced low levels of compliance compared to countries that had legal disclosure requirements, such as the United Kingdom.

End notes

[1] See Recommendation 24 and 25 in: International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism & Proliferation, (Paris: FATF, updated March 2022), 22, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/recommendations/pdfs/FATF%20Recommendations%202012.pdf; Directive (EU) 2018/843 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive (EU) 2015/849 on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing (AMLD5), Articles 30 and 31, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32018L0843&from=EN.

[2] Methodology for Assessing Technical Compliance with the FATF Recommendations and the Effectiveness of AML/CFT Systems (Paris: FATF, updated October 2021), 111, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/methodology/FATF%20Methodology%2022%20Feb%202013.pdf.

[3] Best Practices on Beneficial Ownership for Legal Persons (Paris: FATF, October 2019), 15, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/Best-Practices-Beneficial-Ownership-Legal-Persons.pdf.

[4] Ibid, 66.

[5] “Open Ownership Principles”, Open Ownership, updated July 2021, https://www.openownership.org/en/principles/.

[6] “Open Ownership Principles – Sanctions and enforcement”, Open Ownership, updated July 2021, https://www.openownership.org/en/principles/sanctions-and-enforcement/.