Measuring the economic impact of beneficial ownership transparency (full report)

Mapping the problem space

Defining beneficial ownership, beneficial ownership policy types, and effective implementation

All econometric research requires a strong definition of the object of analysis – in this case, beneficial ownership transparency reforms. The need for strong definitions is particularly salient in the beneficial ownership policy sphere, given that in a number of countries, there is no strong definition (legal or otherwise) of beneficial ownership information at all. [12]

As argued by Open Ownership, having a clear definition of beneficial ownership is crucial for governments looking to minimise loopholes and make beneficial ownership data as useful as possible. [13] For the purposes of this project, we take the definition of beneficial ownership used by Open Ownership. This broadly posits a beneficial owner as:

“a natural person who has the right to some share or enjoyment of a legal entity’s income or assets (ownership) or the right to direct or influence the entity’s activities (control). Ownership and control can be exerted either directly or indirectly.” [14]

The means by which beneficial owners can achieve this ownership or control can be complex, ranging from shareholder agreements to more informal arrangements and ties of kinship. Specific legal contexts also play a role in how ownership structures function across countries. [15] However, given that this is an exploratory piece which seeks to identify how multiple methodological approaches might quantify the impact of BOT across a range of country contexts, the project takes a broad view of beneficial ownership. More specific questions around definition, such as establishing thresholds for disclosure, are crucial for governments to establish, but will not be a primary focus of this work.

Whereas this piece is broad in its definition of beneficial ownership data, more detail is required when looking to define how beneficial ownership transparency can be implemented, which can vary greatly across jurisdictions. How a government chooses to implement these reforms will determine how effective a BOT regime is, and consequently will have an effect on the types of benefits which can be measured and their scale.

Literature in the beneficial ownership space points to a double movement in the political economy of BOT, between what can be characterised as formal and effective beneficial ownership transparency, which we define below. On the one hand, there is a large amount of formal international momentum in the policy area, captured in statements of aspiration and international prohibitions on anonymous firms, such as FATF recommendations, OECD principles on corporate governance, or the UN Convention Against Corruption. [16] [17] [18]

Research suggests, however, that these more formal declarations do not always translate into the kind of effective implementation which can be classed as effective reform. For instance, Sharman (2011) and Allred et al. (2017) present interesting and rare examples of ‘participation’ studies, where the authors attempt to themselves create shell companies, finding that firms in OECD countries were less compliant with international norms and laws relating to firm anonymity than firms in developing countries and tax havens, despite their official commitments to BOT. [19] [20]

In order for a BOT reform to be truly effective, it needs to meet a number of criteria based on data availability and usability, which can be broadly categorised under three headings, in line with Open Ownership’s principles for effective disclosure: [21]

Ensuring the disclosure and collection of data

- Policy which establishes robust definitions for beneficial ownership with sufficiently low thresholds to account for an effective level of transparency

- Policy which mandates the comprehensive disclosure of beneficial ownership data for all companies (with limited exceptions which are frequently reassessed)

- Policy which mandates the disclosure of key data fields (potentially conforming with an established data standard or template) which allow data to be easily interpreted

Ensuring data availability and accessibility

- The creation of a centralised beneficial ownership register

- Policy which ensures that the information available on this register is available to all for free under an open access licence

- Policy which ensures that data is available in a structured, machine-readable and bulk-downloadable format

- Policy which allows other government authorities to access data (including data which is not available publicly due to an exemption) facilitating cross-country anti-corruption activities. [22] [23]

Ensuring data quality and verifiability

- Policy which mandates that beneficial ownership data should be frequently updated, with an auditable record of all changes made publicly available

- Policy which ensures that data is periodically cross checked and verified to ensure that any discrepancies can be detected and reported

- Setting out sanctions (both monetary and non-monetary) for companies or individuals who do not comply with any of the policies above

- Making data on sanction enforcement publicly available.

These policies can then be further distilled into a range of implementation design choices, which will determine to what extent a BOT regime can be classed as effective. The table below sets forth a non-exhaustive list of different examples of design choices which could lead to effective implementation.

| Effective BOT design choice | Implementation examples |

|---|---|

| Centralised beneficial ownership register (vs. non-centralised register.) | A number of countries, including the whole of the European Union, have committed to creating a centralised beneficial ownership register that covers the whole economy. [24] In other contexts, however, registers can be sector specific. For instance, in Myanmar the government has implemented a registry specifically for companies and owners linked to the extractives industry. [25] |

| Publicly available data set (vs. restricted access ‘closed’ dataset.) | Beneficial ownership information databases can have varying levels of open or restricted access. For example, the UK’s PSC register is publicly available (although some limited data is only available to the government, such as beneficial ownership data of companies with voting shares admitted to trading in UK or EU markets). In contrast, the USA made a commitment to implementing a beneficial ownership register in 2021, but one without publicly available data. [26] In other scenarios, a register might operate on a ‘legitimate interest’ basis, providing information to certain user groups, such as NGOs or journalists, but not to the wider public. |

| Free access for all (vs. paid access model) | Certain registries, such as the UK’s PSC Register, mandate the disclosure of all beneficial ownership information (with limited exceptions) under an open access licence. Other countries have opted for paid models, such as the Netherlands, where users need to register and pay a fee of €2.55 per data extract. [27] |

| API publicly available (vs. no API) | An Application Programming Interface (API) enables interactive access to a database, making it possible to automatically query fields and reducing the need for manual analysis. For example, the Companies House API allows developers to retrieve real time information on company information in the UK. [28] |

| Machine readable data (vs. non machine readable or unstructured data) | When data is available in a structured format in bulk, then multiple records can be analysed together, allowing for improved detection of irregularities. Bulk downloadable data which is available in a structured format, such as JSON, can help drive the development of new products aimed at identifying corruption cases and carrying out due diligence. [29] |

As these examples illustrate, BOT regimes are not homogeneous and can be implemented with varying levels of commitment to the principles of coverage, openness, accuracy and verifiability which make beneficial ownership data a useful and reliable resource.

For econometric analyses of BOT, this represents a challenge. First, the varying levels of implementation mean that measuring the impact of BOT across countries is likely to be very difficult at present, given how BOT regimes – and importantly, their benefits – vary in different contexts. A potential strategy for addressing this complexity could be to classify BOT regimes into intervention ‘typologies’ ranging from countries which have no BOT regime in place, through to regimes with partial coverage, paid access models with full coverage, and finally countries with centralised, free-to-access BOT registers.

However, even if implementations are simplified into typologies, there are multiple benefit variables of BOT. Measuring all these benefits at an aggregate level within a single model is likely to be incredibly complex and result in estimations with high margins for error. Therefore, following the advice of economic experts consulted, the report takes a simpler view of measurement, considering how approaches could measure impact according to the classes of benefit that can be expected to derive from a BOT intervention.

Crucially, however, measuring according to benefit type does not involve completely discarding the nature of implementation as an important factor. A number of approaches discussed in this report employ “difference-in-differences” methodologies, which require comparing the average change of a variable across jurisdictions which either have or have not implemented a BOT regime over time. Using implementation typologies to define what can and cannot class as an effective BOT regime will be crucial to conducting these approaches in a way that is sensitive to the fact that not all BOT regimes are equally effective.

Moreover, certain benefits can only be achieved if governments commit to the policies which constitute effective BOT. Logic modelling exercises, as discussed in the following section, can help to demonstrate how these particular design choices feed into the different classes of benefits discussed in the report.

Defining the expected benefits of a BOT intervention: a logic model approach

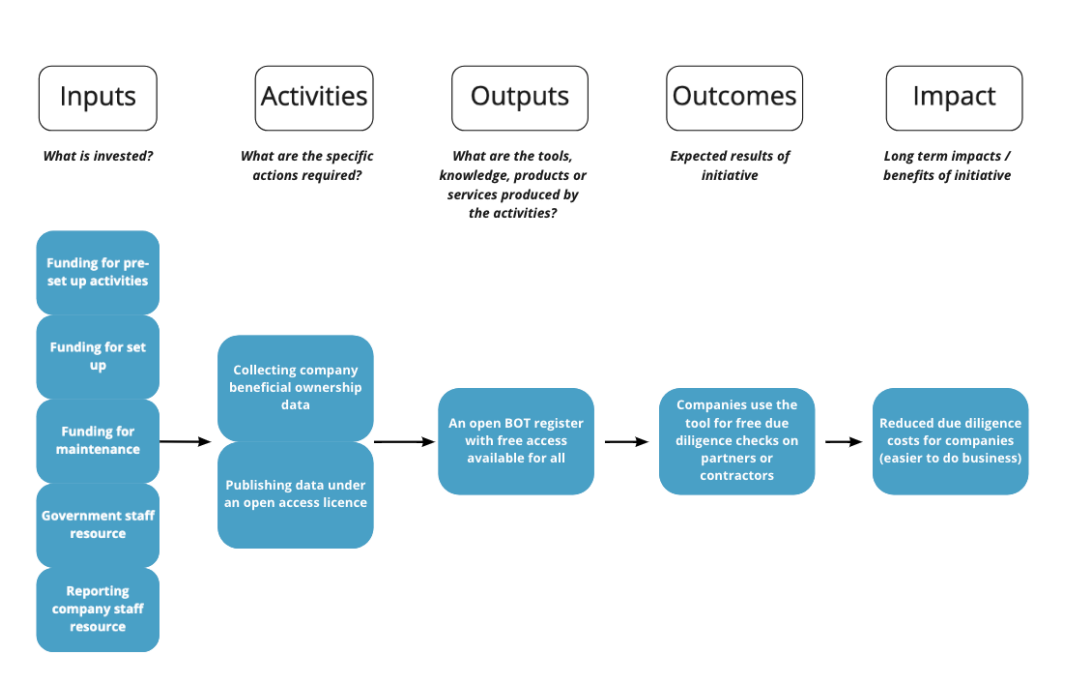

To anticipate the kinds of benefits which would logically arise from different BOT reforms, we used logic models. Logic models are graphic representations of the ways an intervention creates impact through causal chains of inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes. [30]

Logic models have already been used in the UK government’s discussions of BOT benefits. A BEIS Post-implementation review of the UK PSC register from 2019 uses a basic descriptive logic model to highlight the relationship between context, inputs, outputs, outcomes and impacts associated with the implemented regulations. [31] We chose to build upon this framework by expanding the model into a larger logic map which helped us identify the specific mechanisms by which various types of BOT interventions lead to economic benefits. The model was then updated iteratively over the course of research, with new benefits, or causal mechanisms identified in interviews with experts and desk research.

A further function of logic modelling was to demonstrate how particular implementation design choices, such as the decision to make a register free, or provide an API, can lead to specific benefits, which are excluded or weakened in the case of less effective implementation types. Below we have included an exemplary chain from the logic model which represents how a specific design choice, in this case making a register freely accessible, can lead to reduced due diligence costs for companies.

In this example, “inputs” or resources invested, enable “activities” – collecting company and publishing data under an open access licence. This in turn creates an “output”, a BOT register with free access for all, which leads to the outcome of companies being able to use the registry to perform elements of due diligence for free. Finally, the financial impact or benefit is that due diligence costs will be reduced for companies, who in this scenario, can turn to a BOT register as a free-to-access resource for helping research the financial backgrounds of prospective partners and contractors.

Defining the costs of beneficial ownership transparency: preparing for a cost-benefit analysis

One advantage of a logic modelling approach is that in determining the benefits that can be logically expected to arise from a BOT intervention, it also allows for indicators to be established, which need to be benchmarked and evaluated over time to demonstrate progress in a particular benefit area.

At the other end of the scale, these models also help to outline the kind of costs that will be associated with the ‘inputs’ needed to generate a reform. Costs of reform are not the primary focus of this report, which focuses instead on how to measure impact. Costs, however, still need to be acknowledged as a fundamental element of a cost benefit analysis; the systematic process by which governments and businesses weigh up the benefits of an intervention minus its costs to determine whether it is economically viable and worthwhile.

The set up and maintenance costs of a BOT registry are the primary costs for governments looking to implement a BOT regime. According to estimates from one early implementer from the UK, the total cost of setting up a registry is estimated to be at least £770,000, with annual operating costs of at least £150,000. [32] 40% of this budget is estimated to be made up of legal fees spent on drafting and reviewing legislation. [33] Elsewhere, the UK government has also estimated their initial set-up costs to be £72,000 to £112,000 for the IT development of the registry and communication to industry, and £225,000 of on-going annual investment for maintenance. [34] How much a register will cost to implement can vary significantly across jurisdictions, and will depend on factors such as whether a BOT register is being built from scratch or as an addition to an existing company information register. [35]

Aside from costs to government, most of the regulatory burden of BOT registers falls on the private sector. Businesses need to commit time and resources to familiarising themselves with regulation, and to reporting their information to a register. In the UK context, a Post Implementation Review of the UK’s PSC register estimates these costs at £649m of one-off costs for UK businesses to familiarise themselves with regulation, collect and submit ownership information, and £87.2 million in annual costs for companies to maintain records and report updates to Companies House. [36]

Other costs are much more indirect, and concern the wider economic effects of introducing regulation. Critical anti-money laundering theory posits substantive compliance costs which distort markets, whilst leading to minimal results in terms of disrupting illicit financial flows. [37] Similar arguments have been applied to BOT; in a response to a public consultation on the UK beneficial ownership register in 2017, one respondent referred to a “chilling effect” on foreign direct investment (FDI) as a potential cost of reform linked to increased regulation for businesses. [38] We found no quantified evidence to support this specific claim, although some studies have discussed losses from regulatory arbitrage – companies circumventing regulation by investing elsewhere – related to the OECD’s Anti Bribery Convention. [39] [40] [41] However, the findings of these studies are ambiguous, and do not point to losses for OECD signatory countries, but for recipient countries with higher rates of corruption, which are likely to receive less and lower quality FDI following the Convention.

Working on the assumption that BOT is an effective policy, a more radical argument around costs could be that the proceeds of criminal financing are so high in certain jurisdictions that impeding them through Anti-Money Laundering (AML) interventions such as a BOT register would have a net negative economic impact. This is perhaps likely to be the case in jurisdictions which have developed niche statuses as money laundering centres. [42] However, as outlined in the main report below, corruption and money laundering, whilst rich in proceeds, have a number of widely acknowledged social and economic harms. Given that it is in the public interest to impede these activities, any initial costs incurred from a reduction in criminal financing are unlikely to be considered in a cost benefit analysis.

A final risk associated with BOT which could be considered a cost concerns the privacy rights of beneficial owners. In some cases ownership transparency may expose individuals as wealthy, or link them to particular business practices, and so make them targets of criminal activity. Public identification of company owners and directors can be a risk, as evidenced in the UK in the 2000s, when the Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty group attacked the homes of directors of Huntingdon Life Sciences, an animal testing laboratory. [43] Whilst an important concern for the security of beneficial owners, particularly in jurisdictions with weaker law enforcement, this risk is unlikely to have significant economic implications, and are usually mitigated by using protected information statuses, which allow vulnerable individuals exemptions from appearing on a public register.

Although the costs outlined above do need to be acknowledged, and could reasonably be fed into a cost benefit analysis of BOT, it is likely that they are small, relative to benefits of effectively implemented BOT and the costs of not implementing reforms. Even without being able to precisely quantify benefits, the literature reviewed strongly suggests that the benefits of effectively implemented BOT would outweigh its costs for both government and businesses. For instance, whilst the costs to business might seem burdensome, we expect they pale in comparison to the reputational cost, reduction in share price, and fines that a business could incur from becoming involved in a corruption or tax related scandal. [44]

In the main section of the report which follows, we focus on how governments or advocacy organisations might look to size these benefits.

Footnotes

[12] Open Ownership, Open Contracting Partnership and Oxford Insights. (2021). Integrity in IMF COVID-19 financing: Did countries deliver on their procurement & beneficial ownership transparency commitments? https://www.openownership.org/uploads/oo-report-integrity-in-imf-covid-19-financing-2021-04.pdf

[13] Open Ownership. (2020). Beneficial ownership in law: Definitions and thresholds. https://www.openownership.org/uploads/oo-briefing-bo-in-law-definitions-and-thresholds-2020-10.pdf

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Financial Action Task Force (FATF). (2021). Recommendation 24: Transparency and beneficial ownership of legal persons. https://cfatf-gafic.org/index.php/documents/fatf-40r/390-fatf-recommendation-24-transparency-and-beneficial-ownership-of-legal-persons

[17] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2015). G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264236882-en.pdf?expires=1647457640&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=E49ECF052BFC43B51451670E2068CB3C

[18] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2004). United Nations Convention Against Corruption. https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNCAC/Publications/Convention/08-50026_E.pdf

[19] Sharman, J.C. (2011). Testing the Global Financial Transparency Regime, International Studies Quarterly. Volume 55, no. 4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2011.00693.x

[20] Allred, B.B., et al. (2017). Anonymous shell companies: A global audit study and field experiment in 176 countries. Journal of International Business Studies. Volume 48. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-016-0047-7

[21] Open Ownership. (2021). The Open Ownership Principles. https://www.openownership.org/uploads/oo-guidance-open-ownership-principles-2021-07.pdf

[22] For instance, in the UK, companies which trade on regulated markets in the European Economic Area, or on other regulated exchanges internationally are exempt from listing their information on the PSC register. Exemptions can also be made in situations where publishing BO information might represent a demonstrable security threat to an individual.

[23] Financial Action Task Force (FATF). (2021). Recommendation 24: Transparency and beneficial ownership of legal persons. https://cfatf-gafic.org/index.php/documents/fatf-40r/390-fatf-recommendation-24-transparency-and-beneficial-ownership-of-legal-persons

[24] Open Ownership. Worldwide commitments and action map. Accessed January 2022. https://www.openownership.org/map/#map

[25] The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). (2020). Myanmar takes steps to reveal the owners of extractive companies. https://eiti.org/news/myanmar-takes-steps-to-reveal-owners-of-extractive-companies.

[26] Open Ownership. (2021). USA adopts a central beneficial ownership register. https://www.openownership.org/news/usa-adopts-a-central-beneficial-ownership-register/

[27] Netherlands Chamber of Commerce. KVK uittreksel UBO-register. Accessed January 2022. https://www.kvk.nl/producten-bestellen/bedrijfsproducten-bestellen/uittreksel-ubo-register/

[28] Companies House. Companies House API Overview. Accessed January 2022. https://developer.company-information.service.gov.uk/

[29] Open Ownership. (2021). The Open Ownership Principles. https://www.openownership.org/uploads/oo-guidance-open-ownership-principles-2021-07.pdf

[30] For a discussion of logic modelling and definitions of each stage in the process, see this logic model template published by the Open Data Institute.

[31] Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). (2019). Post-Implementation Review of the People with Significant Control Register. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2017/694/pdfs/uksiod_20170694_en.pdf

[32] Davila, J., et. al. (2019). Towards a Global Norm of Beneficial Ownership Transparency. Adam Smith International. https://adamsmithinternational.com/app/uploads/2019/07/Towards-a-Global-Norm-of-Beneficial-Ownership-Transparency-Phase-2-Paper-March-2019.pdf

[33] Ibid.

[34] Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS). (2014). Final Stage Impact Assessments to Part A of the Transparency and Trust Proposals (Companies Transparency). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/324712/bis-14-908a-final-impact-assessments-part-a-companies-transparency-and-trust.pdf

[35] Davila, J., et. al. (2019). Towards a Global Norm of Beneficial Ownership Transparency.Adam Smith International. https://adamsmithinternational.com/app/uploads/2019/07/Towards-a-Global-Norm-of-Beneficial-Ownership-Transparency-Phase-2-Paper-March-2019.pdf

[36] BEIS. (2019). Post-Implementation Review of the People with Significant Control Register. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2017/694/pdfs/uksiod_20170694_en.pdf

[37] Pol, R. Anti-money laundering: The world's least effective policy experiment? Together, we can fix it. Policy Design and Practice. Vol. 3, No. 1, https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2020.1725366. pp. 73-94.

[38] BEIS. (2017). Beneficial ownership register: Summary of responses. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/606411/beneficial-ownership-transparency-summary-responses.pdf

[39] Brazys, S. and Kotsadam, A. (2020). Sunshine or Curse? Foreign Direct Investment, the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, and Individual Corruption Experiences in Africa. International Studies Quarterly. Volume 64, no. 4. https://academic.oup.com/isq/article-abstract/64/4/956/5919191?login=false

[40] Cueva-Cazurra, A. (2008). The effectiveness of laws against bribery abroad. Journal of International Business Studies. Volume 39. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400372

[41] D’Souza, A. (2010). The OECD Anti-Bribery Convention: Changing the currents of trade. Journal of Development Economics. Volume 97. no. 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.01.002

[42] Unger, B. and Rawlings, G. (2018). Competing for criminal money. Global Business and Economics Review. Volume 20, no. 3. https://www.inderscienceonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1504/GBER.2008.019987

[43] BBC News. (2018). Huntingdon Life Sciences terror plot couple sentenced. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-42811033

[44] Davila, J., et. al. (2019). Towards a Global Norm of Beneficial Ownership Transparency.Adam Smith International. https://adamsmithinternational.com/app/uploads/2019/07/Towards-a-Global-Norm-of-Beneficial-Ownership-Transparency-Phase-2-Paper-March-2019.pdf

Next page: Main report: measuring the economic impact of BOT