Measuring the impact of beneficial ownership transparency in public procurement: Starter guide

Why beneficial ownership information matters in public procurement

Public procurement is one of the government’s most effective tools for delivering public goods and services. It is a primary interface between the public and private sectors. Knowing who really owns and benefits from companies bidding for government contracts helps protect limited public resources, prevent financial losses, and ensure funds are used for their intended purpose, ultimately benefitting citizens.

Public procurement is also a prime target for corruption, abuse of power, and fraud. Vulnerabilities arise from the scale of financial resources involved and the discretion afforded to public officials in decision-making processes. A lack of transparency about who truly benefits from government contracts exacerbates these risks (Box 1).

Box 1. Flood control scandal in the Philippines leads to calls for accelerated beneficial ownership transparency

A flood control corruption scandal in the Philippines is still unfolding at the time of writing. It has implicated sitting Senators, members of the House of Representatives, staff of the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), and others in the business community. Testimonies indicate that vast sums were diverted via shell companies and collusive firms, with the Department of Finance estimating losses of roughly PHP 118.5 billion from 2023 to 2025. [2] The DPWH itself has warned that anomalies could amount to trillions of pesos. [3] The case has led to graft and corruption charges, and sharpened calls to accelerate BO transparency in public procurement, amongst other measures. [4] These calls build on the Philippines’ 2024 New Government Procurement Act provisions, which require BO disclosure through an online, public register, as well as recent efforts led by the Government Procurement Policy Board to integrate BO data into procurement systems. [5] By 2027, BO information will be required to be used to check whether a company or any of its beneficial owners have been blacklisted, and to check for conflicts of interest (COIs) among officials involved in the procurement process who may have an interest in a bidder directly or through family connections.

When there is no clear visibility of beneficial ownership networks or financial interests of participating companies, opportunities for abuse are more difficult to detect and prevent. Over the past decade, BO registers of legal entities have become a global standard. [6] Jurisdictions investing in BO transparency reforms will need to proactively measure the benefits if they are to understand whether reforms lead to positive social and economic outcomes.

In many cases, BO registers were primarily created to combat money laundering, and their potential additional benefits in public procurement are significant. [7] This is recognised by the international anti-money laundering (AML) standard-setting body, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which specifies under Recommendation 24 that authorities should have access to BO information in the course of public procurement. [8] Given the direct benefits that can accrue for citizens, public procurement should be a high priority for BO transparency implementation and impact measurement.

It is important to note that the use of BO information from a register at different stages of public procurement will, in many cases, be critical for maximising impact. [9] This is true whether it is used by procurement officials as part of an administrative function; by internal auditors or investigators; or by external actors, such as civil society organisations, as a form of public scrutiny. This guide refers to, but does not offer detailed guidance on, how to use BO data in public procurement processes. The following country case studies illustrate how BO information is already being used for this purpose.

Broader effects may also result from a policy change, even without proactive data use. For example, it may be possible to observe the impacts of a transparency policy on the behaviour of actors such as bidders or other firms (Box 2). This guide touches on these effects, but mainly focuses on measuring impacts resulting from active data use.

Box 2. Impact of beneficial ownership transparency in the British real estate market

A 2025 paper evaluated whether BO transparency can deter anonymous and potentially illicit investment in real estate, using the United Kingdom (UK) as a test case. [10] It studied the introduction of the 2022 Economic Crime Act, which created a public Register of Overseas Entities requiring offshore companies that own UK property to disclose their beneficial owners. [11] The authors combine comprehensive UK land register data with company ownership records covering all property transactions in England and Wales from 2018 to 2024. They apply a difference-in-differences methodology, comparing changes in property purchases, sales, and ownership stocks by companies registered in tax havens (where ownership secrecy is typically highest) to those from non-haven jurisdictions before and after the Act was announced in February 2022.

The study finds a clear and persistent decline in new property purchases by offshore companies registered in tax havens following the announcement of the law and accelerating when the public register becomes operational, consistent with transparency raising the cost of anonymous investment. In contrast, the authors find no strong evidence of increased property sales by offshore owners, meaning that the overall stock of tax-haven-owned property falls only modestly. The paper concludes that public BO registers can be effective at deterring new anonymous real-estate investment, but incomplete implementation has led some clients to still successfully shield their ownership information.

Country case studies

Slovakia employs a dual BO registration system for legal entities: the Register of Public Sector Partners (RPSP), established by national law in 2017, and the AML register, mandated by European Union (EU) directives. The RPSP was established as a response to public concerns over the involvement of anonymously owned companies in state contracts. Unlike the general AML register, its specific aim is public procurement and spending transparency. It requires any entity receiving over EUR 100,000 in state contracts or subsidies, or over EUR 250,000 annually, to register and disclose verified BO information via a certified intermediary. This public register is overseen by a district court which has special jurisdiction over it. It imposes legal consequences for noncompliance, including fines and contract nullification, and retains historical data for retrospective analysis.

Research from 2021 highlighted the RPSP’s effectiveness. [12] It has broad coverage with over 24,000 registered entities, including foreign companies, and has successfully identified beneficial owners behind companies in secrecy jurisdictions. Of the 1,670 foreign entities registered, only a small fraction were linked to high-risk jurisdictions. Even among those, most had Slovak or Czech beneficial owners. Compliance rates are high, with few violations reported. The RPSP operated at an estimated annual state cost of around EUR 700,000, while the private sector bore higher compliance costs. Nonetheless, the administrative burden was generally viewed as proportional to the transparency achieved; the system provides significant deterrent power and has notable cross-border transparency effects. For example, the Slovak register was used to detect a COI case during the first term of Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, who is currently under pressure again to resolve COIs before taking office, following his recent re-election. This case demonstrates how registers can be used to detect, sanction, and prevent COIs. [13]

Chile has significantly reformed its public procurement system to enhance transparency, fairness, and integrity, notably by integrating BO information into oversight processes. Spearheaded by ChileCompra and supported by civil society, this reform mandates BO data collection for companies involved in high-value public tenders and sensitive sectors. A pilot programme successfully linked company-level BO disclosures with the Mercado Público platform, Chile’s digital procurement portal, creating a new system to flag potential COIs, collusion, or undisclosed relationships between bidders and public officials based on BO information.

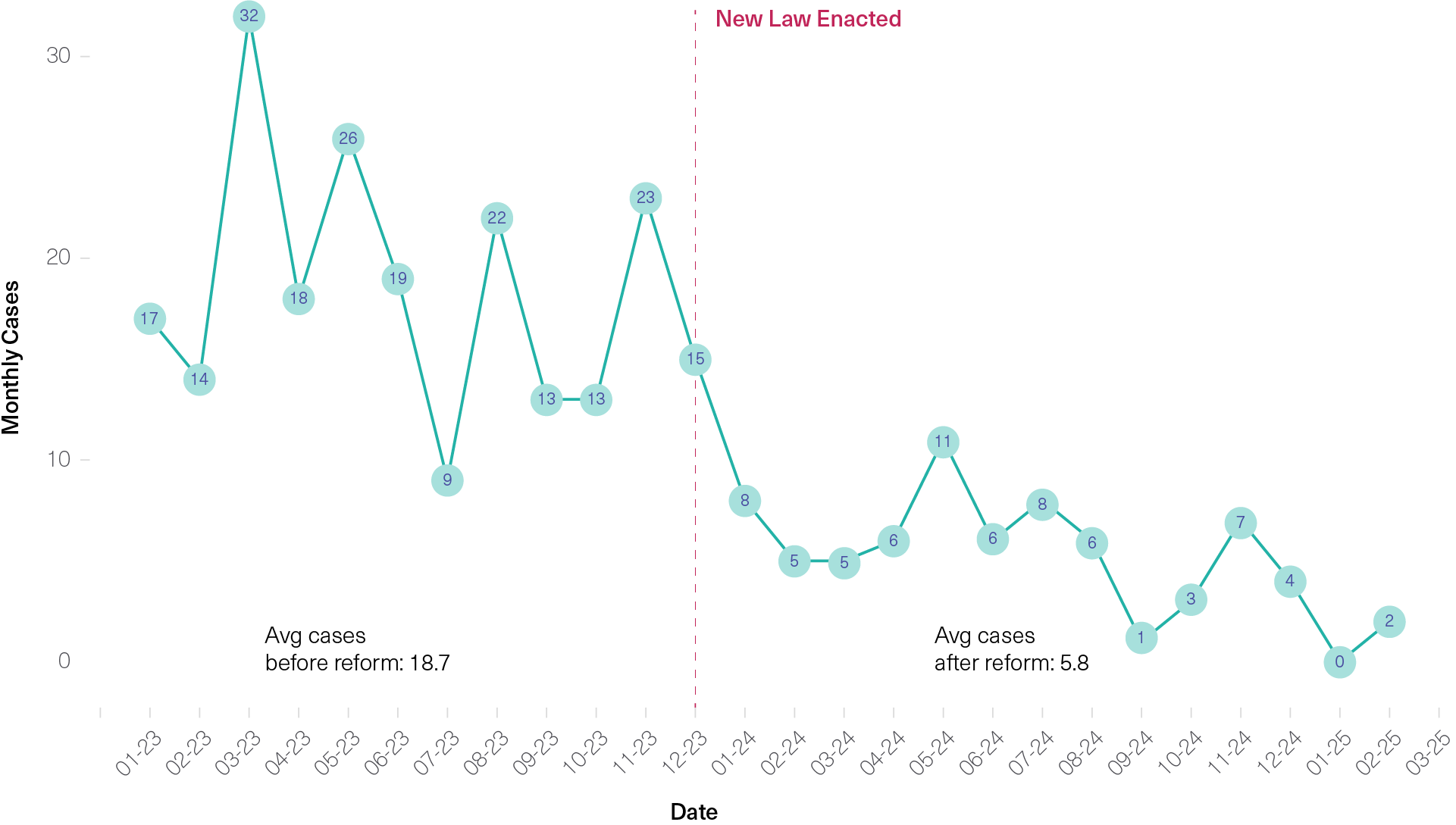

Figure 1. Monthly detected cases of conflicts of interest before and after public procurement reform [14]

BO data is being used to support red-flagging mechanisms and to identify links between bidders and politically exposed persons (PEPs) or previously sanctioned firms. [15] The initiative enabled authorities to detect inconsistencies between declared owners and actual control structures, leading to further scrutiny of certain bids. The number of COI cases identified decreased by 69% since the reform was first introduced. Though challenges remain, this initiative has also spurred journalistic investigations into procurement corruption risks, highlighting the value of interoperability between BO registers and procurement systems for real-time integrity checks.

Footnotes

[2] The Straits Times, “Philippines commission to probe widening flood project scandal”, 13 September 2025, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/philippines-commission-to-probe-widening-flood-project-scandal.

[3] Sherylin Untalan, “DPWH: Trillions may have been lost to anomalous flood control projects”, GMA News Online, 18 September 2025, https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/topstories/nation/959541/dpwh-trillions-may-have-been-lost-to-anomalous-flood-control-projects/story.

[4] Jay Hilotin, “Philippines flood control scam: 25 people slapped with ‘non-bailable’ graft, corruption charges”, Gulf News, 11 September 2025, https://gulfnews.com/world/asia/philippines/philippines-18-people-slapped-with-graft-corruption-and-malversation-charges-over-flood-control-scam-1.500265022; James Patrick Cruz, “DPWH reopens bidding for local projects. What safeguards are in place?”, Rappler, 16 September 2025, https://www.rappler.com/philippines/dpwh-reopens-bidding-local-projects-safeguards/.

[5] Republic of the Philippines, LawPhil Project, Government Procurement Reform Act, Republic Act No. 12009, 20 July 2024, https://lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra2024/ra_12009_2024.html; Republic of the Philippines, Government Procurement Policy Board, home page, n.d., https://www.gppb.gov.ph/.

[6] Open Ownership, “Open Ownership map: Worldwide action on beneficial ownership transparency”, n.d., https://www.openownership.org/en/map/.

[7] Tymon Kiepe and Eva Okunbor, Beneficial ownership data in procurement (Open Ownership, 2021), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/beneficial-ownership-data-in-procurement/.

[8] FATF, International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism & Proliferation: The FATF Recommendations (FATF, updated 2025), https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/publications/Fatfrecommendations/Fatf-recommendations.html.

[9] Julie Rialet, Understanding beneficial ownership data use (Open Ownership, 2025), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/understanding-beneficial-ownership-data-use/.

[10] Matthew Collin, Florian M. Hollenbach, and David Szakonyi, The End of Londongrad? Ownership transparency and Offshore Investment in Real Estate (EU Tax Observatory, 2025), https://www.taxobservatory.eu/www-site/uploads/2025/03/The-End-of-Londongrad.pdf.

[11] Mike Ward, “Register of Overseas Entities – what, why and when – Companies House”, Companies House, 21 November 2022, https://companieshouse.blog.gov.uk/2022/11/21/register-of-overseas-entities-what-why-and-when/.

[12] Daniel Zigo and Filip Vincent, “‘Beneficial Owners’ Policy: Comparison of Its Efficacy in the West with Prospects for Curbing Corruption in China”, DANUBE 12, no. 4 (2021): 273-292, https://doi.org/10.2478/danb-2021-0018.

[13] Tymon Kiepe, Victor Ponsford, and Louise Russell-Prywata, Early impacts of public beneficial ownership registers: Slovakia (Open Ownership, 2020), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/early-impacts-of-public-beneficial-ownership-registers-slovakia/; Jan Lopatka, “Czech president tells prime minister hopeful Babis to show how he will end conflicts of interest”, Reuters, 12 November 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/czech-president-tells-prime-minister-hopeful-babis-show-how-he-will-end-2025-11-12/.

[14] Guillermo Burr and Rodrigo Félix Montalvo, Beneficial ownership in Chile’s public procurement reform (Open Ownership, 2025), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/beneficial-ownership-in-chiles-public-procurement-reform/.

[15] Burr and Montalvo, Beneficial ownership in Chile’s public procurement reform.

Next page: Measuring the impact of beneficial ownership transparency in public procurement