Using beneficial ownership information in fisheries governance

Background

This section provides an introduction to BOT, charting its emergence as a concept in tax and AML policy to its broader relevance today, followed by an introduction to various regulatory frameworks that govern fisheries.

Beneficial ownership transparency

The ability for corporate vehicles to be abused to commit a range of crimes and hide their proceeds has led to calls for better information about the individuals who ultimately own, control, or benefit from corporate vehicles – the beneficial owners. Since the 1970s, AML has been the primary policy driver and use case for countries to implement reforms to ensure a range of parties have access to up-to-date information on beneficial owners. Since the 2000s, governments’ collection of BO information through corporate vehicles’ up-front disclosure to central BO registers has been growing as a key part of the approach to AML.

Up-front disclosure involves governments defining beneficial ownership in law and placing a legal requirement on corporate vehicles in their jurisdictions – initially focusing on legal entities, such as companies, but increasingly also on legal arrangements, such as trusts – to disclose their beneficial ownership and any changes to it within a defined period of time to a government authority in charge of a central register. That information is subsequently verified, stored, and made available to a variety of users. This can range from very few users (e.g. law enforcement) to many other users, including other government agencies, AML-regulated entities, other businesses, civil society organisations (CSOs), journalists, and the general public. [10]

Expanding policy areas and applications

Following the implementation of the first registers in the mid-2010s, the application of BO information collected in central government registers has outgrown the policy area of AML to include anti-corruption and public procurement, taxation, land and property, natural resource governance, and national security. Of these, strengthening natural resource governance was one of the first policy areas where BOT gained traction. In 2016, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) included BOT as a requirement for certain companies involved in the extractive industries of member countries as a means to prevent and detect corruption, with preference for BO information to be collected in a central public register. [11] The increasing availability of information to a widening set of users – both within and beyond governments – has led to new use cases being identified beyond the prevention, detection, and investigation of crime. Regardless, AML – and, specifically, the requirements set by the international AML standard-setting body, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) – remains a major policy driver. Other international mechanisms like the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) have the potential to gain importance in improving and setting standards for BOT, although to date the FATF is more influential in setting specific implementation requirements. The FATF has effectively required the implementation of central registers since 2022. [12]

Beneficial ownership of assets

In recent years, there has also been an increasing focus on the beneficial ownership of assets, which in terms of implementation has focused mainly on land and real estate. This development has been primarily driven by taxation and inequality [13] as well as tackling money laundering, including through non-domestic corporate vehicles. [14] However, there are differences between the beneficial ownership of a corporate vehicle that is the legal owner of an asset and the beneficial ownership of the asset itself. These two often seem to be conflated in the discourse, although the distinction is also critical to the discussion of BOT in fisheries, as explored in more detail later on.

Beneficial ownership transparency and fisheries

Calls for increased transparency in the fisheries sector – including for the collection, use, and publication of BO information – preceded the implementation of central registers. Regardless, the sector and policy area have been trailing behind. [15] In recent years, these calls have been growing louder. They come from a range of multilateral organisations (notably, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, or UNODC) and CSOs that have extensively documented fisheries-related crimes (including corruption) as well as adjacent crimes by transnational organised criminal groups, and the laundering of the proceeds. [16] The global partnership loosely modelled on the EITI’s multi-stakeholder process, the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI), has repeatedly called for BOT in the fisheries sector. However, there remains a gap in the literature in terms of how BO information and central government registers can practically contribute to fisheries governance. To date, most countries do not appear to collect or use information on which individuals own and control corporate vehicles and assets in the fisheries sector. [17]

With global AML requirements effectively mandating them, the majority of countries have implemented or are implementing central BO registers. [18] However, when digital systems are developed without end users in mind they are unlikely to meet users’ specific needs and enable the use cases that lead to impact. In addition, emerging research shows that countries pursuing domestic policy objectives implement more effective reforms than countries seeking to comply with international standards. [19] Therefore, in order for the fisheries sector to benefit from the reforms already underway, it is critical to sketch out the potential use cases for BO data and ensure that both BOT and fisheries policymakers have a basic understanding of the use cases of BOT in fisheries and can engage potential users as part of the reform process. The fisheries sector can apply transparency lessons from the extractive industries, notably on licensing. Contrary to when the recommendation for BO registers entered the EITI Standard in 2016, there is now a bigger body of knowledge to draw from based on the significant progress that has been made in BOT of corporate vehicles since then. [20]

Fisheries regulatory framework

The following section will provide an introduction to the international and domestic policy and regulatory frameworks that govern fisheries as well as the various challenges the fisheries sector faces, identifying both direct and indirect use cases of BO information from central registers.

Global governance

The governance of fisheries is a patchwork of international, regional, and national rules and regulations, which overlap in some areas whilst also leaving significant gaps in others. Broadly speaking, these various regulatory and oversight mechanisms aim to balance the desire to maximise catches with conserving fish stocks. They seek to enable sustainable and equitable exploitation of fish stocks by setting, monitoring, and enforcing limitations on how many different fish species can be exploited within a given area, as well as what methods can be used to do this, and by whom. As all territorial waters are connected by the oceans, and fish and vessels can move across borders, international collaboration is required. There is a significant degree of variance across countries and regions in the processes, methods, and oversight mechanisms employed to achieve these objectives.

The main relevant international legal framework is the 1994 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This grants states the right to exploit marine resources within their exclusive economic zones (EEZs) – the area spanning approximately 200 nautical miles beyond their shores – whilst also placing an obligation on them to ensure that their use of marine resources is carried out sustainably. [21] Together with the 1995 United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA), the UNCLOS also establishes obligations for states to collaborate over the management of highly migratory fish stocks and those that move between different EEZs. [22] This collaboration may be done via direct negotiations between the relevant states or through RFMOs. RFMOs tend to have a geographic remit or focus on particular species. These institutions were established by the UNFSA to achieve and enforce conservation objectives, both on the high seas – beyond EEZs – and in areas under national jurisdiction. RFMOs’ responsibilities include collecting and analysing relevant information, for example on certain fish stocks. They provide a platform for deciding, coordinating, and enforcing fisheries management measures, including setting limits on catch quantities and the number of vessels allowed to fish. These measures are negotiated by the members, and some may need to be incorporated into the domestic legislation of member countries, covering the types of gear that can be used, species of interest, and reporting requirements, among other things.

The majority of marine fish stocks fall under the management of one or more RFMOs. [23] However, there are also areas, such as the South Atlantic Ocean, that do not fall within the remit of an RFMO, allowing, for example, anyone to fish outside of Argentina’s EEZ without any requirement to register, obtain a licence, or report their catch. [24] Areas outside of EEZs which are not covered by the remit of any RFMOs are typically subject to little policing and control. RFMOs vary widely in their effectiveness, and their regulations only bind their member states, which are relied on for compliance, reporting, and enforcement. [25] In addition, most RFMOs struggle to reach consensus on binding conservation and management measures; where they do, these are often not stringent enough to prevent overfishing. [26]

Fisheries tenure systems

These rules and regulations filter down to national regulations and fisheries tenure systems. Fisheries tenure refers to the rights and responsibilities with respect to who is allowed to use which resources, in what way, for how long, and under what conditions; how these rights are allocated; and who is entitled to transfer rights (if any) to others, and how. There is significant divergence in national fisheries tenure systems, but this usually involves governments setting limits for fishing particular species within a season, known as the total allowable catch (TAC), and allocating these to different parties. Some TACs are set in a transparent manner and are based on independent scientific evaluations of the sustainable level of exploitation of different fish species, but many are not. [27]

Sometimes country-level TACs are divided among sub-national authorities before being further allocated. Authorities issue licences or authorisations to fish for quotas for species as well as specific fishing methods, locations, and operating periods as a precondition for fishing and selling catch. [28] Generally, these licences are issued to one or more individuals or corporate vehicles, or both, and they are often tied to a specific vessel. In some countries, such as Namibia and the United Kingdom (UK), the owner of the vessel is required to match the name on the licence. [29] Quotas can be issued to groups of fishery producers known as producer organisations (POs). In other countries, there are no specific quotas, and licenced fishing is allowed by all operators until the TAC is reached, based on reporting of landed catch. In many countries, fisheries tenure is characterised by secrecy and confidentiality. [30]

TACs can be divided among operators in a range of ways, including awards to the highest bidder at auction; in line with historical catch data; or based on some other criteria. For example, in the UK, fixed quota allocations (FQAs) initially allocated when the system was introduced were calculated based on each vessel’s share of landings during 1994-1996. [31] No new licences are created, and there is a limited number in circulation. [32] Countries may also protect the tenure rights of indigenous peoples or communities that have a long history of fishing, either through ownership rights of fishing grounds or through specific licences. [33] For example, the Seychelles provides relatively cheap licences for small vessels that are 100% owned or beneficially owned by citizens of the Seychelles. [34]

Robust systems for quota allocation should include checks and balances to ensure that the process is undertaken in an equitable and independent manner, but in many contexts the criteria upon which quota allocation decisions are made are also not transparent. [35] There have also been cases where a government minister or official has significant discretion to award quotas with seemingly little transparency or oversight. [36]

Liberalisation of fisheries tenure systems

A considerable challenge for transparency and oversight exists in countries which allow quotas to be freely sold and leased. [37] The notion that licences should mimic private property gained popularity in the late 1970s and early 1980s, based on the assumption that the most efficient harvesters will accrue additional licences and quotas as less efficient harvesters exit the market. [38]

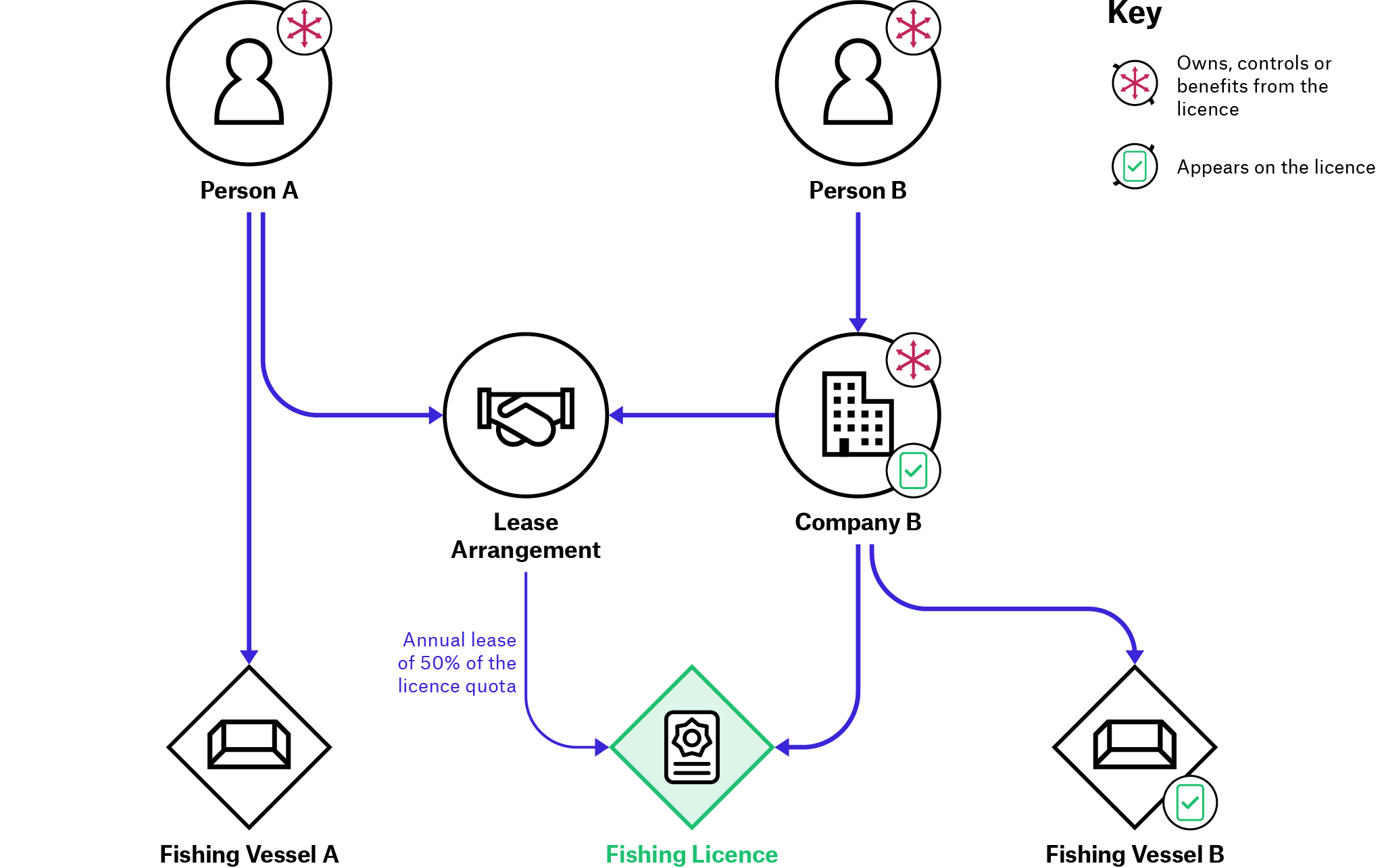

Therefore, it is possible for multiple parties to have an interest in – own, control, or benefit from – the rights associated with the licences, such as the quota. These parties may not appear on the licence itself as the legal owners. Interests may be ultimately held by the legal owners’ beneficial owners, but additional interests may exist, particularly where certain rights are separated through arrangements or agreements. This would be the case, for example, where one owner holds the fishing licence whilst the quota is used by another party, or where a single vessel is registered as holding the lead quota but then leases parts of this quota to other vessels and operators (see Figure 1). In some systems, the purchaser of a quota may not even be required to be licensed or a locally registered fishing operation, enabling agents and brokers to also play a significant role in fisheries tenure. [39]

Figure 1. Illustrative example of parties to a lease arrangement of a fishing licence

In this example, Company B and Fishing Vessel B are authorised to fish a specific quota through a fishing licence. Person B owns and is the beneficial owner of Company B. Person A leases 50% of the licence, and fishes this quota using Fishing Vessel A. Despite other parties (i.e. Person A operating Fishing Vessel A) owning, controlling, or benefitting from the licence, only Company B and Fishing Vessel B appear on the licence.

Licence and quota registers

There are no international agreements or obligations on whether and how governments should collect and share information on parties that have an interest in fisheries tenure, although there are non-binding and voluntary guidelines. [40] Some countries record information about licensing and quotas in a register, but these are often not made publicly accessible. [41] Requirements for gathering such information, and the quality of the data contained within these registers, varies significantly between jurisdictions. In addition, especially where tenure systems have been liberalised, the names on these registers may not provide much information about the beneficial ownership of these quotas and licences. In addition, many areas fall exclusively under the remit of an RFMO, rather than a national jurisdiction.

The application for issuing and renewal of fishing licences as well as vessel registration (see Box 1) are key interactions with authorities and mechanisms for governments to collect information on the individuals who own, control, and benefit from fisheries activities. Many of the other activities in fisheries happen outside the view and control of the authorities, and they rely heavily on reporting and inspection. For example, to enable monitoring, licencees often must report information about the type, location, and quantity of fish caught, and where they were landed. This is challenging to verify and enforce. For example, ships can also – both legally and illegally – transfer catch from one ship to another at sea, known as transhipment. Many states conduct inspections and official checks at landing sites, onboard inspections, and the compulsory use of CCTV equipment or human observers on fishing vessels. [42]

Box 1. Vessel registration and licensing

When applying for a licence to fish or to access a quota in a given country, there are often – but not always – requirements to provide details on the registered vessel that will be used for the fishing operations. In some countries, the registered owner of the vessel needs to match the party applying for the licence. The question of vessel ownership has its own complexities and challenges, and it relates to a broader range of policy areas than fisheries, such as the enforcement and evasion of economic sanctions. [43] Therefore, whilst this briefing does cover the potential use cases of BO information relating to vessels for fisheries governance, it does not cover how and where this information can practically be collected. [44]

As with licensing, there are hugely differing approaches to vessel registration, and no binding international agreements or requirements about how and where ships should be registered. [45] Vessels are often not registered in the jurisdictions where those that have an interest in the vessel may be located. This can be a different location altogether from where a vessel holds a fishing licence and the location of its primary fishing activities. [46]

A vessel on the high seas needs to be registered in a country and fly its flag, and is subsequently subject to its laws. A vessel can re-register in a different jurisdiction, but it can only be registered in one country at a time. Under UNCLOS, states can set their own conditions for allowing the registration of vessels nationally and are responsible for enforcing the conditions and exercising law enforcement jurisdiction over vessels registered with them, and flying their flag. [47] Vessel registers that are open to foreign-owned ships are known as open registers. [48] Some jurisdictions set very few conditions – for example, with respect to safety and labour regulations – and carry out few inspections and enforcement actions, providing a competitive advantage to registration. [49] One study found that most vessels involved in illegal fishing in its sample were registered in jurisdictions with no requirement to disclose the true owners of the vessel. [50] In another study, of all vessels involved in IUU fishing, 70% were flagged in financial secrecy jurisdictions. [51] Research suggests that as regulations change, IUU fishing vessels reflag to jurisdictions with weaker governance. [52]

Certain classes of vessel must obtain a ship number from the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), a UN body responsible for shipping-related security, safety, and environmental issues. All motorised inboard fishing vessels of less than 100 gross tonnage and 12 metres in length or more, authorised to operate outside waters under the national jurisdiction of the flag state as well as all ships over 100 gross tonnage are required to obtain unique IMO identification numbers. [53] This number stays the same even if the owner changes or the vessel changes the country in which it is nationally registered. [54] Ownership information disclosure is required in order to obtain an IMO number but does not include BO information. [55] In one study, more than 60% of vessels linked to illegal fishing activities in the sample did not have an IMO number, suggesting that the owners of these vessels have a preference for registering their vessels in registers that do not require IMO numbers. [56] Countries can have different requirements for domestic and foreign vessels, and may collect IMO numbers (or other identifiers) or other vessel registration information as part of licence applications.

The fisheries value chain

The fisheries value chain is a framework that splits fisheries activity into multiple stages, which allows for the evaluation of where BO information can be used directly and indirectly, and identifies potential risks that arise from ownership opacity (Figure 2). The following section will explore how BOT can improve fisheries governance, using the stages of the fisheries value chain as a framework. [57]

Figure 2. The fisheries value chain and typical activities in various stages

The list of activities under each stage is not exhaustive. Additionally, fishing, processing, and sales can frequently be done by different parties or corporate vehicles and occur in different places, with different currencies and reporting requirements. [58]

Footnotes

[10] For more information, see: Open Ownership, Guide to implementing beneficial ownership transparency (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2021), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/guide-to-implementing-beneficial-ownership-transparency/; Open Ownership, Open Ownership Principles for effective beneficial ownership disclosure (s.l.: Open Ownership, updated 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/principles/; “What is beneficial ownership transparency?”, Open Ownership, n.d., https://www.openownership.org/en/about/what-is-beneficial-ownership-transparency/.

[11] EITI, The EITI Standard 2016, (Oslo: EITI, 2015), https://eiti.org/documents/eiti-standard-2016.

[12] FATF, Public Statement on revisions to R.24 (Paris: FATF, 2022), https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/publications/fatfrecommendations/documents/r24-statement-march-2022.html.

[13] For example, the idea of a global asset register was first developed by Thomas Piketty. See: Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wpqbc. The BOT of financial assets has also been suggested to lead to an increase in real estate investments. See: Jeanne Bomare and Ségal Le Guern Herry, Will We Ever Be Able to Track Offshore Wealth? Evidence from the Offshore Real Estate Market in the UK (Paris: EU Tax Observatory, 2022), https://www.taxobservatory.eu//www-site/uploads/2022/06/BLGH_June2022.pdf.

[14] For example, the report from the Expert Panel on Money Laundering in BC Real Estate (Maureen Maloney, Tsur Somerville, and Brigitte Unger, Combatting Money Laundering in BC Real Estate, (Victoria: Expert Panel, 2019), https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/housing-and-tenancy/real-estate-in-bc/combatting-money-laundering-report.pdf) led to the creation of British Columbia’s Land Ownership Transparency Registry (LOTR) (see: “Land Transparency. Protected”, Home page, LOTR, 2024, https://landtransparency.ca/; Government of British Columbia, Canada, Land Owner Transparency Act (LOTA) [SBC 2019], Chapter 23, Section 2, “Meaning of ‘beneficial owner’”, 2019, https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/19023#section2). Similarly, concerns about illicit funds being invested in the London real estate market (see: Mike Ward, “Register of Overseas Entities – what, why and when”, Companies House, UK Government, 21 November 2022, https://companieshouse.blog.gov.uk/2022/11/21/register-of-overseas-entities-what-why-and-when/) led to the creation of the UK’s register of overseas entities owning UK property (see: Department for Business and Trade, Companies House, HM Land Registry, and Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, UK Government, “Register of Overseas Entities”, updated 28 June 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/register-of-overseas-entities).

[15] See, for example: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Evading the Net: Tax Crime in the Fisheries Sector (Paris: OECD, 2013), https://www.oecd.org/ctp/crime/evading-the-net-tax-crime-fisheries-sector.pdf; FiTI, Transparency of fisheries tenure: Incomplete, unreliable and misleading? (s.l.: FiTI, 2020), https://www.fiti.global/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/FiTI_tBrief02_Tenure_EN.pdf.

[16] See, for example: UNODC, Transnational Organized Crime in the Fishing Industry – Focus on: Trafficking in Persons Smuggling of Migrants Illicit Drugs Trafficking (Vienna: UNODC, 2011), https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/Issue_Paper_-_TOC_in_the_Fishing_Industry.pdf; UNODC, UNODC Approach to Crimes in the Fisheries Sector (Vienna: UNODC, n.d.), https://www.unodc.org/documents/Wildlife/UNODC_Approach_to_Crimes_in_the_Fisheries_Sector.pdf; UNODC, Fisheries Crime: transnational organized criminal activities in the context of the fisheries sector (Vienna: UNODC, n.d.), https://www.unodc.org/documents/about-unodc/Campaigns/Fisheries/focus_sheet_PRINT.pdf; UNODC, Stretching the Fishnet: Identifying crime in the fisheries value chain (Vienna: UNODC, 2022), https://www.unodc.org/res/environment-climate/resources_html/Stretching_the_Fishnet.pdf; UNODC, Rotten Fish: A guide on addressing corruption in the fisheries sector (Vienna: UNODC, 2019), https://www.unodc.org/documents/Rotten_Fish.pdf. Other organisations include: the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), FTI, Global Financial Integrity, and the OECD. There are also calls for transparency in the beneficial ownership of vessels. Because the question of vessel ownership has its own complexities and challenges, and because it relates to a broader range of policy areas than fisheries, the beneficial ownership of vessels will be addressed in more detail in a separate upcoming paper.

[17] FiTI, Fishing in the dark: Transparency of beneficial ownership (sl.l: FiTI, 2020), 8, https://fiti.global/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/FiTI_tBrief03_BO_EN.pdf.

[18] “Open Ownership map: Worldwide action on beneficial ownership transparency”, Open Ownership, n.d., https://www.openownership.org/en/map/. Other international bodies and mechanisms endorse, encourage, or require central registers, including UNCAC and the European Union (EU).

[19] Barry, “Exploring patterns of beneficial ownership reform”.

[20] EITI, The EITI Standard 2016.

[21] United Nations (UN), “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea”, 1994, https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf. In addition, there are a number of environmental and other international agreements which may be relevant to fisheries. These include, for example, the FAO Compliance Agreement, the Agreement on Port State Measures (PSMA), the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal’s (SDGs), the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, the Work in Fishing Convention 2007 (ILO188), the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), as well as World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules, for example on subsidies, and other voluntary measures and initiatives: UK Government, Fisheries Management and Support Common Framework: Provisional Framework Outline Agreement and Memorandum of Understanding (London: Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2022), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/62068f21d3bf7f4f0981a0c7/fisheries-management-provisional-common-framework.pdf.

[22] “UNFSA Overview”, UN, Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, n.d., https://www.un.org/oceancapacity/unfsa. The UNCLOS has been ratified by 168 countries and the EU, with China as a notable exception. The UNFSA has been ratified by 92 states and the EU, with the US as a notable exception. See: Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, Office of Legal Affairs, UN, “Chronological lists of ratifications of, accessions and successions to the Convention and the related Agreements”, 24 October 2023, https://www.un.org/Depts/los/reference_files/chronological_lists_of_ratifications.htm.

[23] Chatham House (The Royal Institute of International Affairs), Recommended Best Practices for Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (London: Chatham House, 2007), 1, https://www.oecd.org/sd-roundtable/papersandpublications/39374762.pdf.

[24] Daniels et al., Fishy networks.

[25] Chatham House, Recommended Best Practices for Regional Fisheries Management Organizations, 1-2.

[26] See: Antonia Leroy and Michel Morin, “Innovation in the decision-making process of the RFMOs”, Marine Policy 97 (November 2018): 156-162, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.05.025.

[27] Evidence suggests TACs consistently exceed sustainable limits. See: “North East Atlantic quota sharing agreement in urgent need”, Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), n.d., https://www.msc.org/species/small-pelagic-fish/north-east-atlantic-quota-sharing-agreement-in-urgent-need.

[28] North Atlantic Fisheries Intelligence Group (NA-FIG), Chasing Red Herrings: Flags of Convenience, Secrecy and the Impact on Fisheries Crime Law Enforcement (Copenhagen: NA-FIG, 2018), 21, https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1253427/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

[29] Fisheries Management Team, Marine Management Association, UK Government, “AFL1: Guidance for Completing the AFL2 Form to Apply for a Fishing vessel Licence”, 6 July 2022, 1, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6398a24de90e077c34f2038c/AFL_1_Master_Version_.pdf.

[30] For more information, see: FiTI, Transparency of fisheries tenure.

[31] UK Government, UK Quota Management Rules (London: Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2023), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/64a553dc7a4c230013bba1c7/UK_Quota_Management_Rules_-_July_2023.pdf.

[32] Amy Wardlaw, “3 questions frequently asked about commercial fishing”, Marine developments, Marine Management Organisation, UK Government, 8 February 2018, https://marinedevelopments.blog.gov.uk/2018/02/08/commercial-fishing-uk-access-licence/.

[33] For example, the Philippines recognises the right of ownership of indigenous communities over “bodies of water traditionally and actually occupied [...] and fishing grounds” in the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act: Republic of the Philippines, “An Act to Recognize, Protect and Promote the Rights of Indigenous Cultural Communities/Indigenous Peoples, Creating a National Commission on Indigenous Peoples, Establishing Implementing Mechanisms, Appropriating Funds therefor, and for Other Purposes – The Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act of 1997”, Republic Act No. 8371, Chapter Three, Section 7 (a), 29 October 1997, https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1997/10/29/republic-act-no-8371/.

[34] “Fishing Licences”, Seychelles Fishing Authority, n.d., https://www.sfa.sc/services1/fishing-licence.

[35] FiTI, Transparency of fisheries tenure.

[36] See, for example: Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR), After Fishrot: The Urgent Need for Transparency and Accountability (Windhoek: IPPR, 2022), https://ippr.org.na/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/HSF-Fishing-2022.pdf.

[37] FiTI, Transparency of fisheries tenure, 7; Anthony Cox, Quota Allocation in International Fisheries (Paris: OECD, 2009), 8, https://www.ccsbt.org/system/files/resource/en/4e37735815a1e/SMEC_Info_01__New_Zealand_OECD_quota_allocation_report.pdf.

[38] Jennifer J. Silver and Joshua S. Stoll, “How do commercial fishing licences relate to access?”, Fish and Fisheries 20, no. 5 (September 2019): 993-1004, https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12393.

[39] Canada House of Commons, “West Coast Fisheries: Sharing Risks and Benefits”, Report of the Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 2019, https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/FOPO/Reports/RP10387715/foporp21/foporp21-e.pdf.

[40] For example, there are voluntary guidelines produced by the FAO (FAO, Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure on Land, Fisheries and Forests in the context of National Food Security, (Rome: FAO, 2022), First revision, https://www.fao.org/3/i2801e/i2801e.pdf). These were endorsed by the World Committee on Food Security in 2012.

[41] FiTI, Transparency of fisheries tenure, 7.

[42] European Parliament, “Fishing rules: Compulsory CCTV for certain vessels to counter infractions”, Press Release, 11 March 2021, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20210304IPR99227/fishing-rules-compulsory-cctv-for-certain-vessels-to-counter-infractions.

[43] For examples, see: Pablo Sapiains and Alex MacDonald, “Sanctions Risks: Deceptive Shipping Practices”, Deloitte, 1 December 2022, https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/blog/economic-crime/2022/deceptive-shipping-practices-eminence.html; “The hunt for superyachts of sanctioned Russian oligarchs”, BBC News, 6 April 2022, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/60739336.

[44] The beneficial ownership of vessels will be discussed in more detail in a separate Open Ownership policy briefing, expected late 2024.

[45] “Registration of ships and fraudulent registration matters”, International Maritime Organization, 2019, https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Legal/Pages/Registration-of-ships-and-fraudulent-registration-matters.aspx.

[46] OECD, Evading the Net, 20.

[47] UN, UNCLOS, Article 92(1), 58, and Article 94(1)–(5), 58-59.

[48] Open registers are sometimes referred to as flags of convenience, but this term has specific negative connotations.

[49] NA-FIG, Chasing Red Herrings, 30.

[50] “Of the 197 vessels used for illegal fishing activities with a known flag state, 162 (or 82.2%) have been registered in [open registers]. Conversely, only 35 (or 17.8%) of these vessels have never been registered in an [open register]. The four most often used flag states for vessels engaged in illegal fishing activities [all have open registers]. [... O]ne of the key “conveniences” of [open registers] is secrecy, i.e. that they enable owners and operators to hide their identity.” NA-FIG, Chasing Red Herrings, 31, 67.

[51] Victor Galaz, Beatrice Crona, Alice Dauriach, Jean-Baptiste Jouffray, Henrik Österblom, and Jan Fichtner, “Tax havens and global environmental degradation”, Nature Ecology & Evolution 2 (2018): 1352-57, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0497-3.

[52] Galaz et al., “Tax havens and global environmental degradation”.

[53] “Global Record of Fishing Vessels, Refrigerated Transport Vessels and Supply Vessels”, FAO, n.d., https://www.fao.org/global-record/background/unique-vessel-identifier/en/.

[54] “IMO Ship and Company Number Scheme”, S&P Global Market Intelligence, n.d., https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/mi/products/imo-ship-company.html.

[55] There is a field on the application form for the IMO Registered Owner to include details on the beneficial owner, but this is not mandatory and the form does not include guidance or a definition of what constitutes a beneficial owner.

[56] NA-FIG, Chasing Red Herrings, 75.

[57] Developed by the OECD and further adapted by UNODC. See: OECD, Evading the Net; UNODC, Stretching the Fishnet; and UNODC, Rotten Fish.

[58] Compiled from: OECD, Evading the Net; UNODC, Stretching the Fishnet; and UNODC, Rotten Fish.

Next page: Use cases of beneficial ownership information to achieve fisheries policy aims