Reconciling beneficial ownership data

Welcome to the second in a series of technical posts about working with beneficial ownership (BO) data. Over the past three years, Open Ownership (OO) has been building a prototype Global Beneficial Ownership Register, in order to prove the feasibility and value of linking BO data across jurisdictions. We have used this project to experiment with a variety of tools and processes, from standardising data under the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS) to providing a search engine, disclosure viewer, data archive, and network visualisation (amongst others). As this phase of our work draws to a close, we are documenting the things we have learned and sharing our experiences with data users and publishers in the public and private sector.

In Part One, we covered the broad concept of modelling BO data, discussing how different needs and local contexts shape how data is stored, queried, and exchanged. This blog post delves deeper into one key aspect of working with that data: reconciling different sources into a coherent whole. We will cover the different strategies one can adopt, such as unique identifiers, reference to external registers, and fuzzy feature-based matching. We will also highlight the schemes that are trying to improve entity identification around the world, detail our own Register’s data model for identifiers, and discuss how reconciliation must evolve over time to adapt to new information.

Why reconcile?

Beneficial ownership reflects the global nature of the modern economy with many companies operating in more than one jurisdiction. However most BO data collection is done at a national or regional level. To transcend these barriers and achieve the aims of beneficial ownership transparency, we need to collect disclosures from multiple sources and link them together. We often also want to link BO data to other datasets, or augment it. This can be done by, for example, getting standard industry codes from company registers, finding people in a list of politically exposed persons (PEPs), or matching companies to the winners of procurement contracts. In order to do these things, we need a process of reconciliation – figuring out which records from each data source refer to the same person, company, or other legal entity. At its heart, then, reconciling data is about identifying individual records.

How can we identify people and companies

With sufficient context, we can easily identify a single person or company in our everyday lives, and it can be tempting to think that this ease translates to reconciling large amounts of data, too. However, the likelihood of finding an error when we are looking for business on a particular high street is much lower than finding an error amongst millions of registered companies in a particular country. Companies can be owned by other parent companies, trade under different names, and old names can be reused. Instead of names, it is common to give companies a unique number or other identifier during their registration and rely on that identifier as their true identity.

OpenCorporates, a global database of companies, highlights that, unfortunately, even company numbers are not always as strong an identifier as one would like. They too can be recycled, ambiguous, or change over time because they rely on extra information such as a registering office or entity type to make them unique.

OpenCorporates apply their own rules to create a unique identifier in these situations, as do other companies such as Dun & Bradstreet with their D-U-N-S number system. The Global Legal Entity Identifier Foundation is another organisation focused on providing strong identifiers for all legal entities, through a federated network of local issuing agents who verify information, then provide a Legal Entity Identifier for a fee.

These globally unique identifiers are the current gold standard for identifying and reconciling companies. However, often when working with BO data such high quality identifiers will not be available. Instead, judgements will have to be made based on the identifiers one already has. Org-Id is a project from Open Data Services Co-operative that aims to describe every organisational identifier scheme in the world and what it is used for, to help with this process.

For people, the concept of a national identity system is much more politically charged. Where they exist, personally identifying numbers are often rightly considered sensitive data that should not be made public. The data most likely to be encountered will usually have no unique identifiers at all, or an identifier that is only used within the BO system.

mySociety have done recent research on approaches to publishing partial or anonymised identifiers, primarily to aid disambiguation, which, if adopted by multiple systems, could also help with reconciliation. Later on in this post we will also talk about approaches that use other data, such as names and addresses, for when identifiers are missing completely.

Identifier-based reconciliation

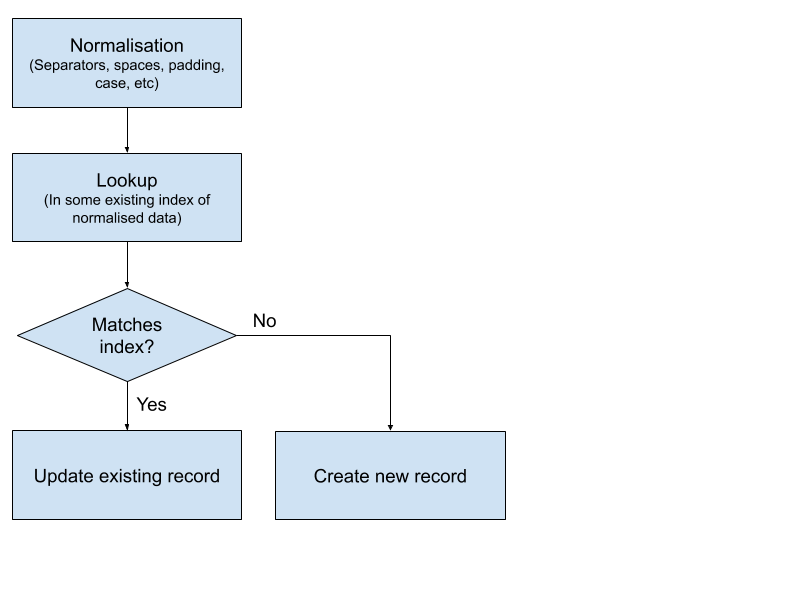

Assuming some kind of identifier(s) are in the data, how does one go about using those to reconcile different data sources? In the simplest form, the process can look something like this:

Flow-chart of the process for a simple lookup of identifiers against an existing index to determine whether an entity is already held in said index.

Normalisation is key here: standardising every identifier so that they have the same format. Data in BO systems is often manually entered and un-verified, so it will be structured in a variety of different ways. It is much easier to match identifiers when they are all in the same format. However, a solid understanding of the format and structure of an identifier system is needed in order to losslessly normalise it. In our own register, we use the OpenCorporates API to normalise company numbers for us, which is the first step in our own reconciliation process.

In order to link data sources, one must be able to connect multiple identifiers to a single record in a system, regardless of the conceptual model used for the data (see Part One for more details on conceptual models). Our own register uses a snapshot model internally, where we have database records for people & companies, then model relationships between them as they are right now. This is as opposed to a statement-based model, where disclosures made by people or companies are the primary database records. We manage identifiers in our model by giving each record a list of them. An individual identifier is made up of a series of key-value pairs taken from the source data and our database ensures that each identifier is uniquely associated with a single record in the database.

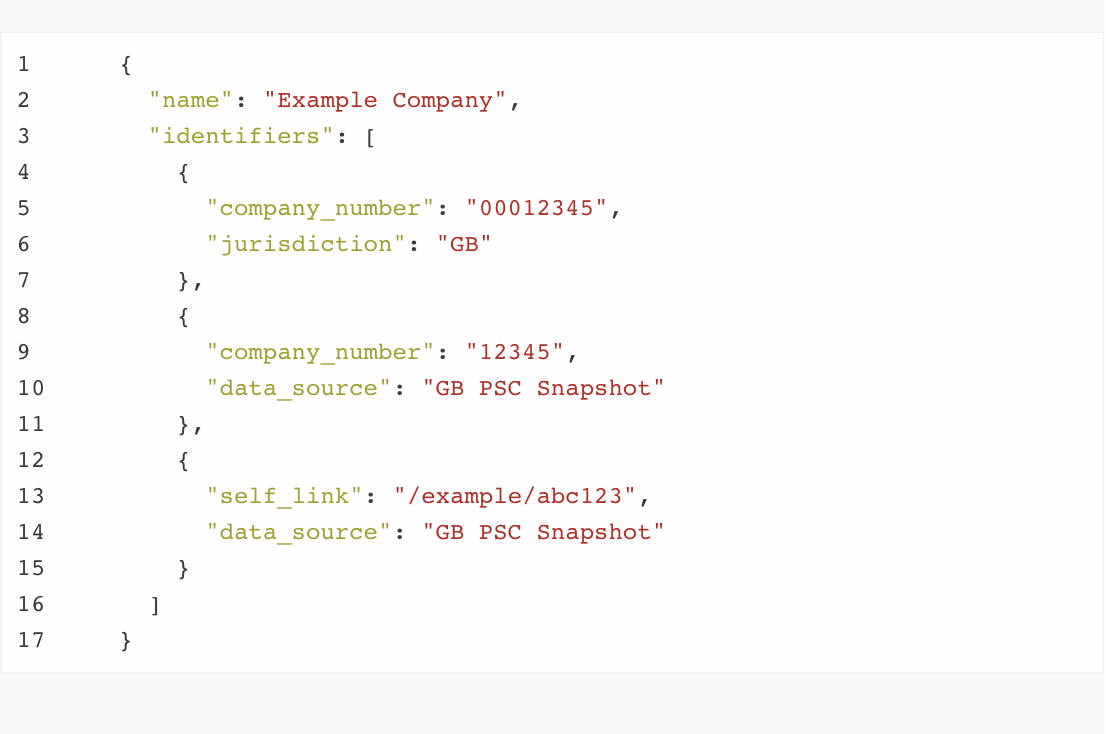

Example data from the Open Ownership Register:

This has two identifiers from the original data source, and then a more normalised version of the company number from reconciliation with OpenCorporates. If we reconcile any other data to that same company number, or see future data with the same internal identifiers, we consider it to be the same company.

We will also merge any additional identifiers into this record, so that we continue to match things in the future. For example, if we saw Example Company in the Slovakian Public Sector Partners register as well, we might end up with identifiers like:

The ICO number is the field in Slovakian data where companies give either their Slovakian company number or a foreign one. The varying number of zeros padding the number is an extremely common situation with UK company numbers.

Using other registers

As we said earlier, the Open Ownership register uses data from another register, OpenCorporates, to normalise and reconcile companies. This is a common approach where one trusts a more specific or authoritative data source to identify one’s own data. We work with OpenCorporates data because it has great global coverage of companies and features built in for reconciling based on more than just company numbers; national registers or other open data sets, such as OpenSanctions, can also be substituted to achieve similar results.

Using another source of data like this is often necessary when working with BO data, because the data itself does not contain everything you might want to know about a company or person. This is usually by design, as you do not want to duplicate data that is available more authoritatively elsewhere. In the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard, our overriding principle for which fields to include is those that are necessary and proportionate to allow disambiguation. This means we do not require previous company names or genders, for example.

The key questions when using another data source are those of trust and coverage. How much will depend on a source, and what precedence will be given to it over other sources, must be decided. A mistake we made in our own register was giving too much precedence to OpenCorporates, which now makes it difficult to manage which data is taken from them and which is not, and to correct the rare situations where their data is outdated.

It is important that one understands exactly what a data source covers. For example, if it is a national company register, does it include charities and trusts? Often, there is data encoded in a company number that gives away some of the information needed to find the right official source, but can it be trusted? In the UK, for example, companies reporting their own beneficial owners must identify themselves by their company number, so these are well verified. But, when a company reports a foreign corporate owner, the identifier given is not checked with that jurisdiction because it would be too onerous a process. This often results in messy or ambiguous identifiers, which are harder to reconcile.

Feature-based reconciliation

When anything less than a verified identifier and a clear authoritative source for it is available, it does not hurt to use additional features of one’s data for reconciliation. If data is messy, or does not have any identifiers at all, feature-based reconciliation is the only way possible. One popular tool for this is OpenRefine, which allows one to connect data to various reconciliation services or APIs. We use an example of this kind of service on our own register: OpenCorporates’ OpenRefine Endpoint, which allows us to reconcile companies by name when we have no company number at all, or the company numbers we have do not match anything.

Name-based matching obviously relies on having the same (or similar) names. This is something that can be complicated by different alphabets – in many national registers in central Asia, for example, there is a mixture of Latin, Cyrillic, and national scripts. Sometimes names will be transliterated from one to the other, with all the variation in results one might expect. In the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard, we advise that names be primarily disclosed in their native alphabet, whatever that might be, and transliterations also be provided. We have a dedicated annotation system to describe how that transliteration process has happened. We recommend the Synonames work by OCCRP for a deeper dive into the ways that names can change across cultural and geographic boundaries.

With all feature-based reconciliation, it is important to acknowledge the fuzziness of the process in one’s system. In our own register, we try to combine records about people by matching exact names, dates of birth, and addresses. Even with those strict criteria, we still make sure the results are transparent to the end user and the process is reversible, so that any mistakes can be spotted and fixed. We will talk more about this specific process in a future post, but the general lesson we have learned is that almost any seemingly unlikely situation will happen at least once when there are tens of millions of rows of data. With a fuzzier matching process, one moves from measuring instances of errors to percentages, and it can be hard to truly get a handle on how well a system is performing.

Addresses

One area where we have experimented heavily with fuzzier approaches to matching data is through addresses. Conceptually, an address is an extremely powerful piece of disambiguating information, but it is also data that typically sees huge variation in formatting and structure. This combination makes it tempting to use, but also complicated. This complexity is why with the BODS, we ask only for a single address string and a separately extracted postcode. We still advise national registers to collect data in whatever local format will give the best experience for users. The complexity of addresses as a national dataset is also why we do not mandate that governments should validate or verify every single address automatically. Several, such as Denmark and the UK, do perform some verification, but it depends on such a wide array of other factors that we cannot require it of everyone.

In our experiments, we have had good results using libpostal to perform some offline normalisation of address strings. This library is trained on open address data and can turn a single string into structured data. Even better is combining this with a reverse geocoding service such as Open Cage or Google. We have found that Google is unbeatable when it comes to global coverage, but no service is infallible. For example, many european countries share a 5-digit postal code format and so it is not uncommon for a short address to be miscategorised as French when it is actually Slovakian. This is simply a bias in the training data: there are a lot more French addresses. Testing any service with a wide range of real data is the only way to be sure, and even then it helps to have some way of cross-checking to catch errors. For example, we use both a geocoder and libpostal to detect a possible company jurisdiction when that data is missing; we tested it by running all of our data through it, even when the field was already present, and comparing the results.

The passage of time

The final important lesson we’ve learnt with reconciliation is that it is never finished. There is always a new piece of data which you need to take into account and which can undo your previous work. This occurs because of the different pace of data releases - your primary sources might be newer than your secondary references for several months, or even a year. On the OO register we counteract this via quarterly ‘whole system’ refreshes of the reconciliation process, on top of our monthly data imports. This can be costly, but it’s the only way to ensure data doesn’t go stale. Stale data is a problem because information needs to be up to date to be usable.

Summary

In summary, the process of reconciliation is one of the most important tasks when using BO data, and it is one that drives many of OO’s technical and policy decisions. It is the concern behind our inclusion of sufficient detail in our principles for effective BO disclosure and one of the key things that is enabled by structured and verified data. As we will see in future posts, it also overlaps heavily with the process of de-duplication and the need to store the history and provenance of data.

Key findings:

- understand primary sources well to make sure one is getting every piece of information out of them and limitations and boundaries are clear;

- establish a clear precedence of secondary sources and a strategy for what to do when conflicts arise;

- when conducting feature-based reconciliation, ensure transparency in processes and the ability to manually correct mistakes; ideally, have a continuous process for cross-checking reconciliations;

- be prepared for continuous reconciliation and refresh your data regularly.

Photo by Maksym Kaharlytskyi on Unsplash

Related articles and publications

Publication type

Blog post

Topics

Beneficial Ownership Data Standard,

Open Ownership Register

Sections

Implementation,

Technology

Open Ownership Principles

Structured data