Campaigning success in Canada leads to new beneficial ownership registers and more

Photo by chris robert on Unsplash

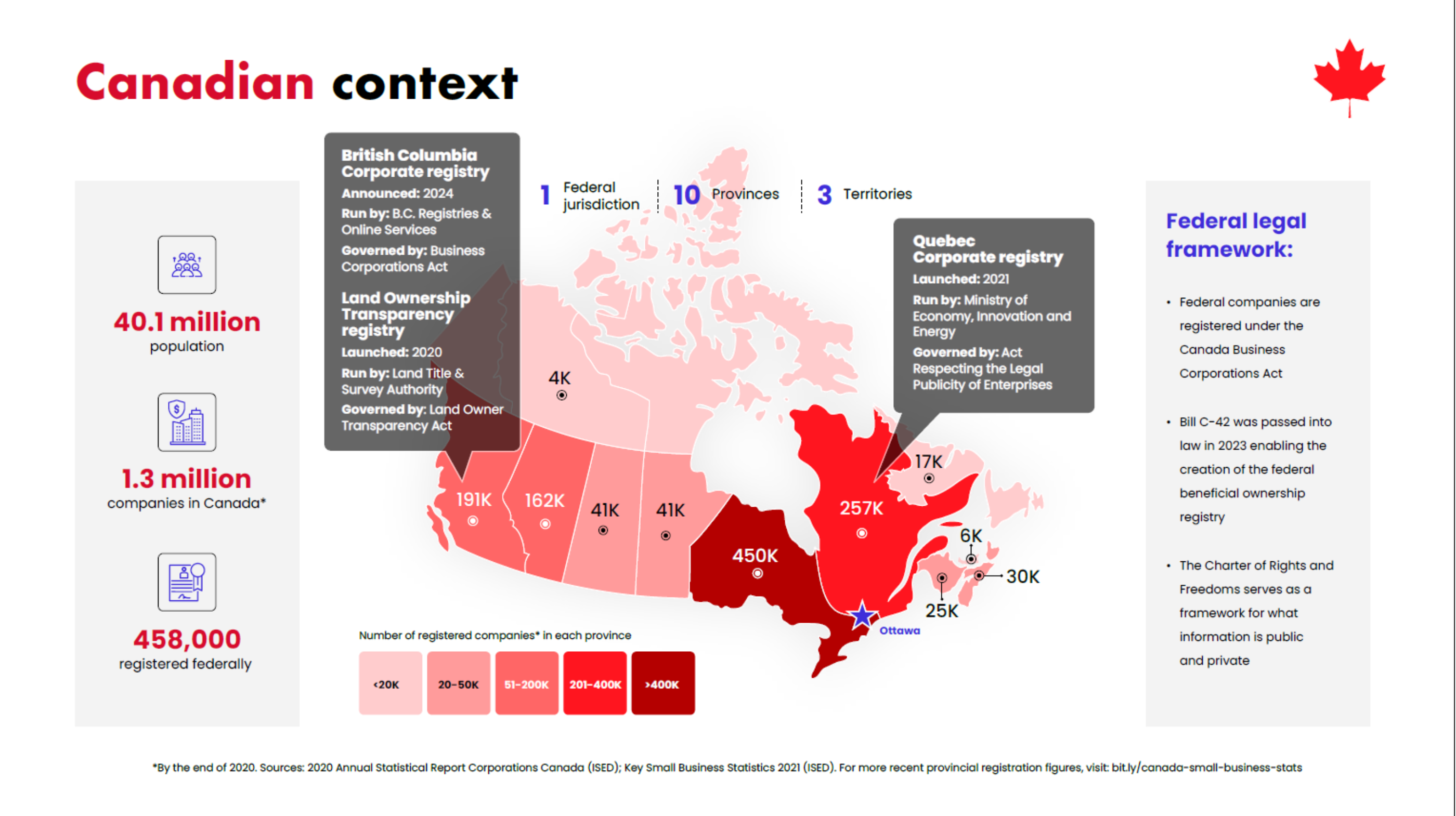

Since 2017, a tireless coalition of non-profits has been advocating for beneficial ownership transparency (BOT) in Canada. These organisations have not only managed to advocate for a law that was passed unanimously by Parliament, but they also secured cross-party agreement that BOT is a solution for money laundering and national security. The federal beneficial ownership (BO) register is now live and actively used by journalists to unmask anonymous company owners, and the new property register in British Columbia (BC) is one of the first of its kind in the world, aiming to uncover the use of real estate for money laundering and corruption.

How did they do it?

Open Ownership (OO) has been working with Canada’s End Snow-Washing Coalition to share their success story and encourage campaigners and advocates in other jurisdictions. In an interview with Sasha Caldera, Campaign Director, we learn about the Coalition’s journey since 2017, including challenges overcome, wins celebrated, and why Canada’s BO reforms are even more relevant in this year’s fast-changing domestic and international political landscapes. Browse a set of infographics created as part of this project to share achievements and learning from the End Snow-Washing Coalition.

Open Ownership (OO): Can you briefly explain why you started with your campaign, your key achievements over the past years, which organisations were involved, and what this has led to?

Sasha Caldera (SC): The campaign started in 2017, and came from a recognition that Canada was being hit hard by money laundering and all the bad stuff associated with it: artificial speculation of housing prices; organised crime; abuse of anonymous shell companies; fraud schemes, which have particularly affected new Canadians and seniors; and an increase in opioids, specifically fentanyl, which has devastated many cities in Canada.

At that point, nobody was talking about how all these things are linked to money laundering, or how to address these issues other than retrospectively through sanctions and enforcement, rather than deterrence. We felt that policy mechanisms were needed to prevent bad actors from profiting from these activities and using anonymous shell companies and properties. This was around the same time as the Panama and Paradise Papers were released, in which Canada was implicated as international law firms were marketing Canada to clients abroad who wanted to incorporate in secret and avoid tax.

The three organisations which came together as a coalition were Canadians for Tax Fairness, Publish What You Pay Canada (fiscally hosted by IMPACT), and Transparency International Canada.

The name came about when we realised there was a negative brand associated with Canada as a destination to “snow-wash” – cleaning dirty money until it is as white as snow. So we chose the name End Snow-Washing.

Key achievements

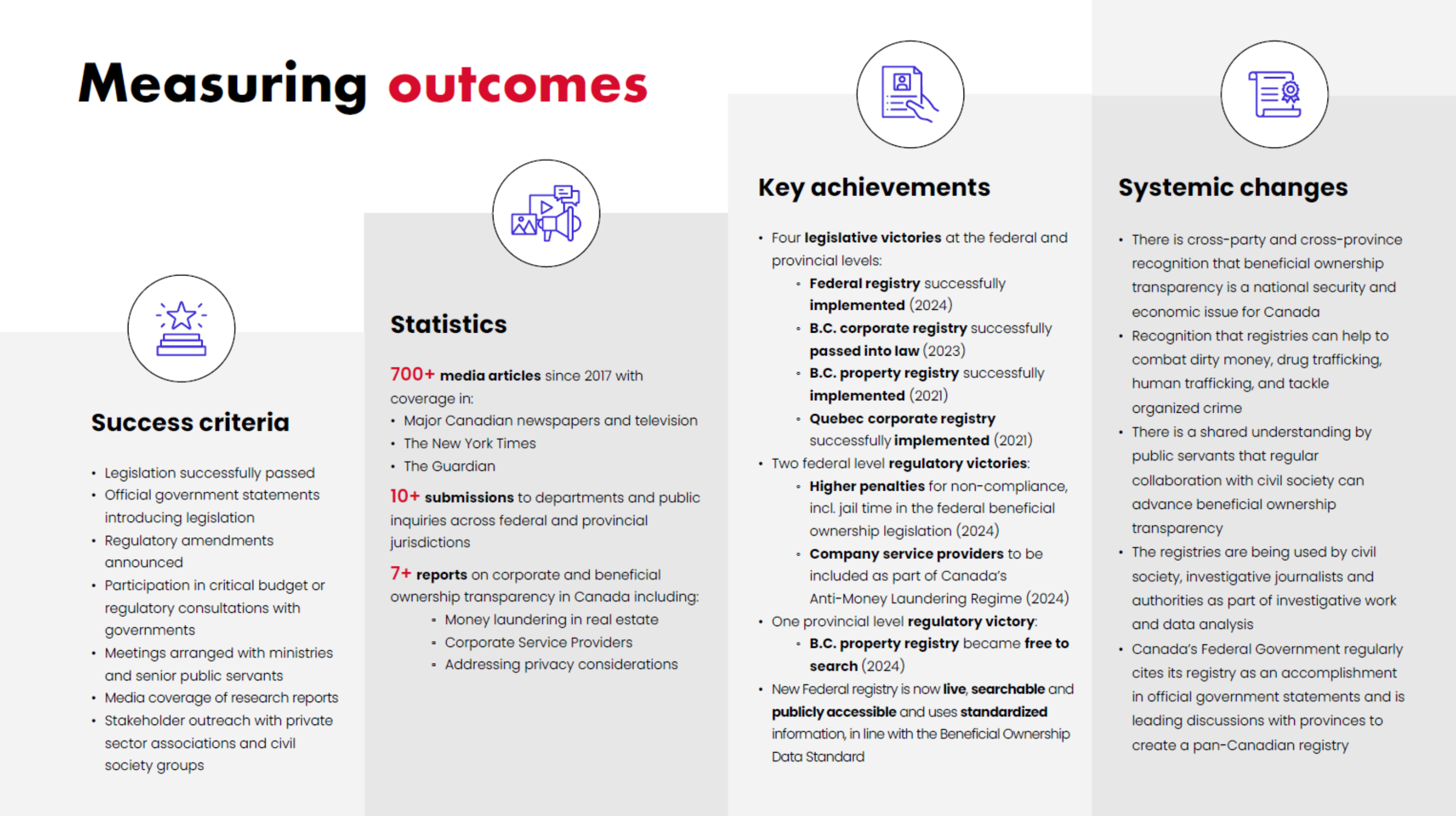

OO: The End Snow-Washing Coalition has had significant success in Canada. Their primary objectives were to get public, searchable, free BO registries for companies and properties implemented in the country. The Coalition has been largely successful: in the past three years, BC, Quebec, and Canada’s federal government have legislated and implemented BO registries (for property in BC, and for legal entities both in Quebec and at the federal level).

They also had a series of regulatory wins:

- The BC registry is now free to use. There was initially a charge of CAD 5 per search, but thanks to the work of the Coalition, it has been free since 2024.

- International corporate service providers recommending Canada as a destination for shell companies were put under Canada’s anti-money laundering legislation. The Coalition’s advocacy efforts led to this change, which included requirements to carry out standard know-your-customer procedures and impose fines.

- The penalty scheme of the federal registry was initially quite weak. Penalties for being knowingly noncompliant were in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, which the Coalition argued is not much of a financial deterrent for criminal organisations. The Coalition helped to increase fines to CAD 1 million and at least five years in jail.

OO: Were there any unexpected challenges?

SC: For me, it was personal. In Richmond, BC, my home town, the whole city has been transformed by real estate-based money laundering. It is completely unaffordable to live there, there are organised crime rings that have proliferated fentanyl into Vancouver and Richmond, and the effects of this can be seen in the communities. This wasn’t the case growing up there in the 1990s.

We wanted to go beyond just doing good advocacy work to being truly successful at creating impact and systems change. We had to secure legislative wins, or nothing. We wanted to really deliver long-term wins that were institutionalised, and helped move the country forward.

“It wasn’t enough to talk about tax evasion being bad, transparency being good, the virtues of fighting corruption… We had to go further.”

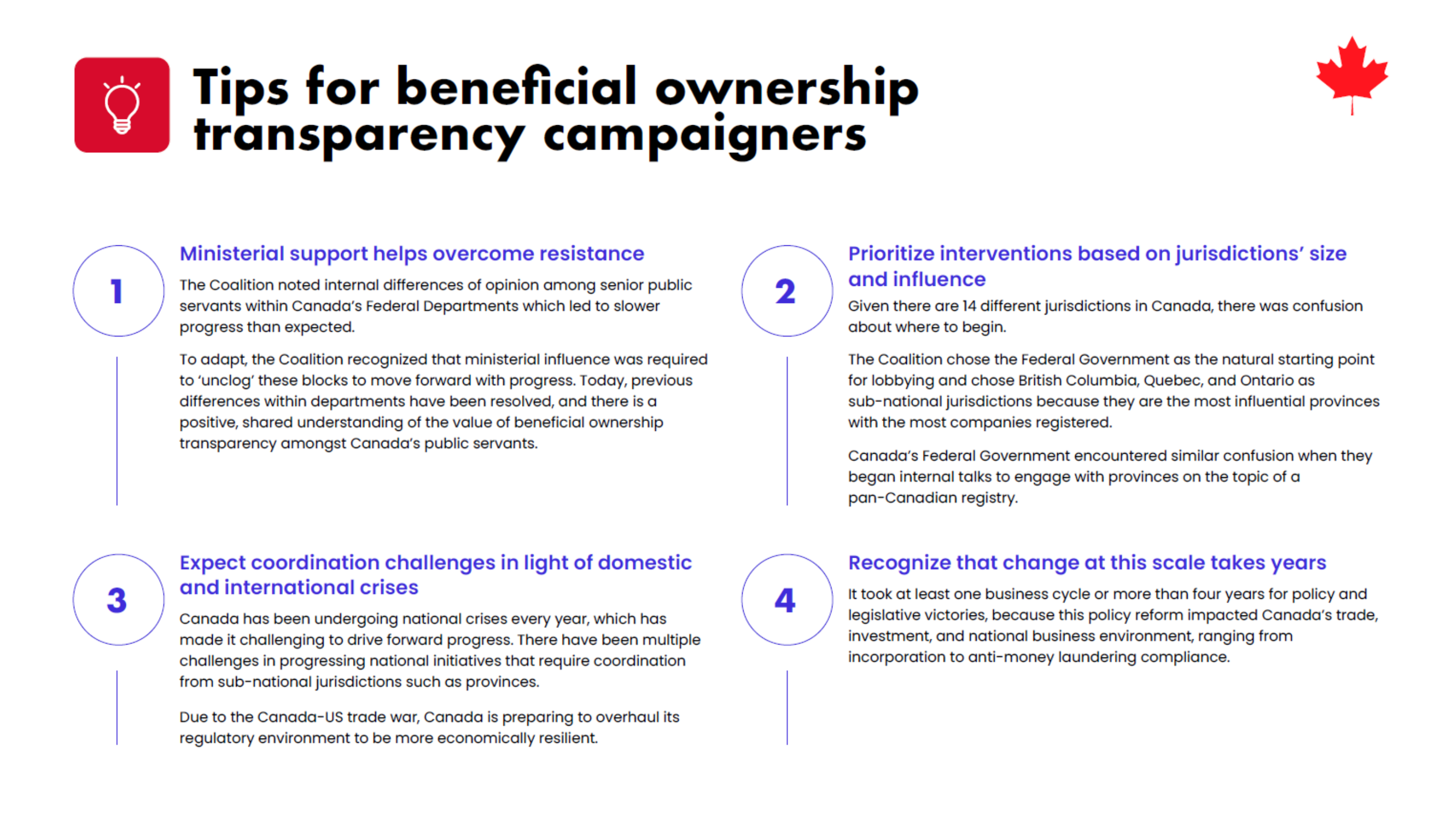

SC: It was challenging to go beyond conventional arguments that seemed natural but were actually ineffective – it wasn’t enough to talk about tax evasion being bad, transparency being good, the virtues of fighting corruption. It would get us meetings, and op-eds, but it wasn’t enough to create real change. We had to go further. In today’s political landscape, when everything is on fire, we have needed bulletproof arguments linked to urgent national issues to get any legislative agenda to be considered.

This took a few years to become good at. We finally reached a value proposition based on Canadian domestic priorities and national security arguments about protecting the integrity of the Canadian economy. These were also linked to Canada’s national housing affordability emergency and large-scale fraud schemes. Furthermore, when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, there was a strong argument for Canada to get its act together, and we linked our argument to these international matters.

SC: Another challenge was recognising that when the government was on the cusp of announcing the federal registry, there were strong differences of opinions between two major government departments. The Department of Finance understood why it was financially beneficial for the country, but Corporations Canada (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada) was sceptical that it would be a burden to businesses. Corporations Canada worried it would negatively affect foreign direct investment into the country and make it more cumbersome to start a company. After several rounds of talks with public servants in those departments and Ministers themselves, we finally achieved success on the federal registry.

One challenge the Coalition foresaw and successfully dodged was the issue of privacy. We quickly recognised that we needed a rock-solid plan on privacy, including a legal basis. At the time of the European Union’s 2019 fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive, we saw that European arguments were not compelling or accurate for Canada. I led on this work, and am particularly proud of it.

The privacy expert we hired to study Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms and privacy acts came up with a very compelling analysis, determining how privacy rights are upheld under certain circumstances. When we shared this legal analysis with some lawyers in opposition to a public BO registry, they were unable to refute it, so we knew we were on the right track. Next, we sent the findings to the Ontario Privacy and Access to Information Commissioner, who concluded that the analysis was sound. It was monumental to have a province officially agree with and back our arguments, and really helped move things forward.

After this, we briefed public servants, the Department of Justice, and the Prime Minister’s office, who supported our stance. Having this strong backing really helped. When there were differences of opinion in the government, those who were on our side used the analysis to push the matter forward and dispel the myth that personal privacy will be compromised while having publicly accessible BO registers.

OO: How did you fund the work and keep up momentum with limited resources?

SC: Sustained funding was key, and this work would not have happened if there had not been support from the Open Society Foundations from the start. This funding lasted from 2017–2024, which was huge. Also, the funding was flexible enough and there were enough resources for us to carry out an effective campaign and advocacy in Canada.

In more recent years, we have been very grateful for support from the BHP Foundation. I hope both Foundations will be proud to see that their investment has resulted in increased transparency that is now institutionalised in Canada, and that this will help to encourage other countries.

SC: We also can’t thank the global civil society and journalist community enough, including OO. We started collaborating with OO in 2019. Working with OO, the Transparency International Secretariat and chapters, the Tax Justice Network, and others globally was invaluable, as we could ask each other questions and share insights and ideas. There were several government consultations in Canada which we recommended that OO be a part of, and OO joined several serious meetings with Canadian public servants to talk about global BO implementation.

I want to thank investigative journalists both in Canada and internationally. The insights shared by these stakeholders and the public coverage of these issues had great non-monetary value. Journalists were always uncovering stories about shell companies, money laundering, and arrests – all of this helped bring the issues to the forefront in the Canadian media over and over again, and tactical insights from civil society were also invaluable. We knew we weren’t going at it alone.

And as we navigate future opportunities and challenges, I know that all these partnerships, with international civil society and journalists, as well as the Coalition’s partners across Canada, will be essential to sharing insights and helping us achieve impact.

OO: What are you most proud of in this work?

SC: There are legislative achievements that are now in law, and the registries are implemented, and I am very proud of that. Although laws can sometimes be repealed, now that the registries are live and working, they are becoming institutionalised. That is the long-term behaviour change we were striving for, along with the institutionalisation of these advocacy victories and reforms, and the regular use of these tools.

The interest level among public servants and the belief that these instruments are being used for good is key, but very few legislative wins actually translate into long-term behaviour change. If you can see the government championing the campaign goal you achieved, then you know you’ve changed things – in the country, in the world – and that’s what we wanted to achieve with this coalition: long-term change, at a systemic level.

“If you can see the government championing the campaign goal you achieved, then you know you’ve changed things – in the country, in the world – and that’s what we wanted to achieve with this coalition: long-term change, at a systemic level.”

SC: I am really proud of how public servants are now championing these registers. Civil society groups like us don't have the same resources as governments. If we make the right case and get the law successfully passed, then the government will also believe in it and advance it – it will become institutionalised. We achieved this success, as we managed to convince public servants and encourage them to advocate for this internally.

OO: Do you have any top tips or tactics to share on what worked for you when things got tough?

SC:

- Reach out to groups that are working on similar issues around the world. Being part of a global community will move things forward: you can lean on each other, learn from each other’s experience, and help derisk the issue for public servants. Listening to perspectives from civil society and public servants in the United Kingdom was helpful for Canadian public servants to learn about registry implementation.

SC:

- Creating specific, targeted arguments is foundational. Keep the overarching themes – anti-corruption, anti-money laundering, and transparency – but to get a country to meaningfully legislate, you need specific, nationally relevant arguments to provide a rationale for why the country needs to do this. Whether housing, natural-resource theft, or tax evasion, look for the domestic crisis issue to use as the primary argument.

- Allow enough time (one business cycle). We thought three years would suffice, and we were dead wrong. We recognised after three years that one of the reasons why a country like Canada was so hesitant on this reform was that it would impact one key aspect of the regulatory regime for all business corporations in the country, and this would have legal and economic implications for the whole country. Working on national-level change will take at least a business cycle, which means at least four and a half years. Setting up a five-year campaign would be a smart foresight.

- Make it clear to funders that flexibility with time will be needed. Advocates working on reform that involves legislation should consider that it will take at least one business cycle, so funders also need to consider this timeframe.

OO: What would you say to advocates or campaigners working on beneficial ownership transparency in other jurisdictions who feel like progress has stalled?

SC: Think critically about why it has stalled, and try to be very honest. Think about what it would take to move things forward. When thinking about the way in which it has stalled, look at specific topics, and look at geopolitical or external factors like COVID.

Could it be the way in which you are going about advocacy? Civil society can help move things forward, but there are ebbs and flows which might mean you need influence from another type of actor. For example, we didn’t have success with the private sector, but we did have success with journalists and in gaining international pressure. Is the stalled progress something within your control? It can be easy to sometimes think, “Is it something we did wrong?”, which means we aren’t moving forward anymore. Instead, take a step back and ask, what would it take to move forward? There are some things within your control, some not – see to what extent you can change the things within your influence.

If you have a receptive government, can you get them to engage with actors in your community of civil society agents, journalists, and international contacts? For example, try connecting them with public servants and civil society actors that were successful in other jurisdictions.

We are currently trying to forge a link between Canada and Australia, as they are facing issues we have already learned how to address. Their BOT regime is more nascent, but both are natural-resource countries, and both are G20 countries. We are certain that, being similar-sized economies, Australian government actors will be able to learn from the Canadian case and contribute to useful advocacy efforts in Australia. We are also regularly in talks with UK civil society and public servants.

OO: What advice would you have for non-profits that are being affected by the current decreased levels of official development assistance and the challenging environment generally? How can they mobilise financial support for BOT?

SC: Right now, the funding environment is the most challenging it’s ever been for Global North and Global South countries. I think foundations can play a major role in supporting country-level initiatives to advance BOT, and I hope multilaterals may consider supporting groups of country-level actors working on long-term research and coordination efforts to advance registry use. Another route worth exploring is learning whether government departments may be offering funding to civil society groups through public safety grants. Key to all of these is making the links between nationally important policy issues and BOT, and as the landscape is changing in many countries we’ll be needing new narratives that reframe BOT beyond a transparency or anti-corruption measure, and highlight its value to things like fair and effective taxation.

OO: How do you see these reforms being relevant to the changing policy landscape in Canada and internationally?

SC: Some of the biggest challenges in the world right now are economic inequality; more specifically, wealth inequality. I think these registries will achieve two things: the deterrence of bad actors from dumping dirty money into economies; and in the longer term, that registries will be setting up a foundation for a wealth tax at a national level and potentially a global asset registry, maybe a decade or more in the future. Whether by money laundering or tax evasion, there is a transfer of wealth from the working and middle classes to the top 1%, and the acquisition of assets, particularly stocks and properties, by the top 1%.

In the discussions on how to address this transfer of assets, a wealth tax is just one idea. But in order to implement a tax reform like this, you need to know who owns what, and that is where BO registries come into play. The long-term objective 15 years from now is a demonstration that these registries actually deter large transnational criminal networks, and can also play a role in deterring tax evasion. To make that happen BO registers need to be used, and civil society needs to help ensure this is happening on a regular basis.