An introduction to trusts in South Africa: A beneficial ownership perspective

Abuse of trust instruments in South Africa

Trusts can be used to hide the identities of the natural persons who own or control assets or companies, sometimes as part of complex ownership chains. Such obfuscation can, in turn, be used for criminal activities, including corruption, money laundering, tax evasion, and the financing of terrorist activities.

Due to the opaque nature of trusts, the true extent of the abuse of trusts for illicit activities is not clear. Trusts can be abused for private and public sector corruption, and the protection of the identity of the beneficiaries and the founder of a trust makes it particularly challenging to identify the natural persons exercising ultimate control over a specific trust.

However, investigative journalists have documented various high-profile cases where politically connected individuals allegedly used trusts to benefit from state tenders without disclosing their involvement. [38]

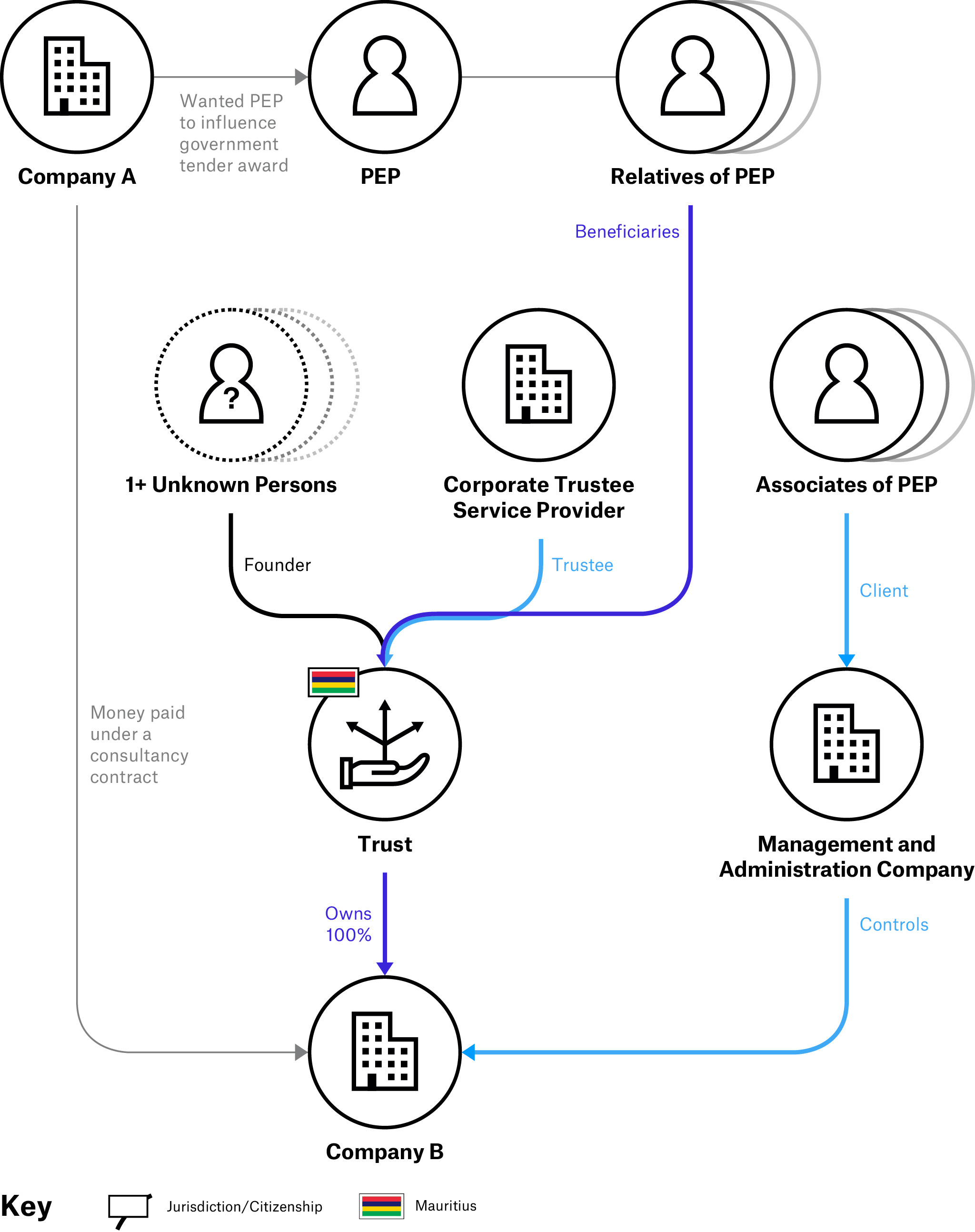

Sources: The diagram above has been compiled from the information in a report by the Financial Intelligence Centre (FIC) on a best efforts basis.

Box 2. Financial Intelligence Centre case study of the use of a trust to facilitate the payment of a bribe to a politically exposed person [39]

The Financial Intelligence Centre (FIC) identified politically exposed persons (PEPs, known in South African law at the time of writing as prominent influential persons (PIPs)) who were paid a bribe by a private sector institution (Company A) to influence the awarding of a contract for the supply of goods to the government. To avoid detection, instead of directly paying the PEPs, Company A paid Company B through a consultancy contract. Company B was managed and administered by a service provider on behalf of the PEPs’ associates. Shares of Company B were placed into a Mauritius-based trust administered by a trust service provider. The beneficiaries of the trust included the PEPs’ family members, allowing the PEPs to indirectly benefit from the bribe.

According to industry experts interviewed, there is an emerging trend of using trusts to facilitate exchange controls avoidance through cryptocurrencies. In these cases, cryptocurrencies are purchased on behalf of trusts and transferred to offshore exchanges, as cryptocurrency transfers are currently under-regulated. As trusts are not linked to individual tax numbers, individuals manage to flout the South African Reserve Bank’s exchange controls. These schemes are increasingly popular in the so-called Chinese Underground Banking System, in which South African citizens are paid by Chinese nationals to facilitate the transfer of financial flows to offshore cryptocurrency exchanges. [40]

Additionally, bad actors can make use of nominees or straw-persons as founders, which entails a third party (oftentimes legal practitioners) establishing a trust on behalf of another natural person, as no checks are conducted on the founder at registration. In these scenarios, the identity of the true beneficial owner is obscured, as there is no documented link (other than potentially a private contract with the third party) to identify the true settlor. In such a case, it is nearly impossible to pierce the veil of a trust, as the third party is bound and protected by the contract to keep the identity of the founder secret. [41]

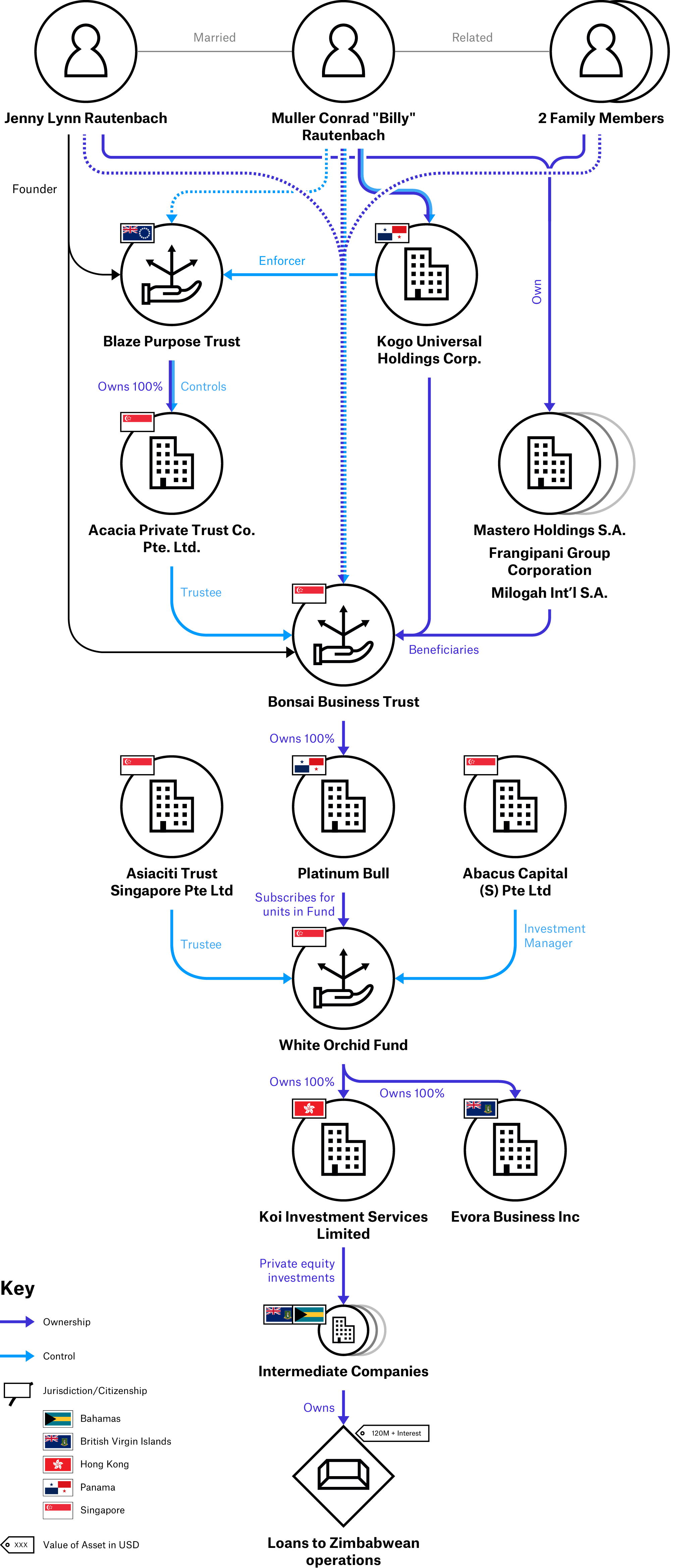

Sources: The diagram above has been adapted from a diagram from the amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism (amaBhungane) using public sources to illustrate the complexity in understanding ownership structures based on limited publicly available information, including reporting from amaBhungane, Daily Maverick, and corporate filings. These sources contain allegations which have been denied by the individuals in question, and some of the legal persons depicted (including Asiaciti) have stated that the information on which it is based contains inaccuracies. The information contained in this diagram is compiled on a best efforts basis and is not exhaustive or complete. Aspects of the ownership structure may have been left out where the information is not available, not relevant to illustrate the story, or challenging to visually represent. The diagram covers a period of time, rather than a snapshot. Some of the entities and officers shown may no longer be active.

Box 3. The Bonsai Business Trust [42]

The Panama Papers revealed a complex structure that was used by Muller Conrad “Billy” Rautenbach, one of Zimbabwe’s wealthiest business figures, to facilitate the flow of illicit funds away from SARS. The structure uses both foreign trusts and corporate structures to obscure the ultimate beneficiary of those funds.

At the top of the ownership structure is the Blaze Purpose Trust. According to investigative journalists, leaked documents show Rautenbach is the sole enforcer and ultimate beneficial owner of this trust through the Panamanian Kogo Universal Holdings.

The Bonsai Business Trust, whose corporate trustee is owned by the Blaze Purpose Trust, was founded by Rautenbach’s wife. As supposed compensation for her role in building the family business, Rautenbach donated financial investments in his coal and ethanol businesses to his wife worth millions of dollars. This donation was transferred to the Bonsai Business Trust, of which Rautenbach indirectly retained ultimate control.

Whilst it is not illegal for individuals or corporations to hold assets for succession planning in offshore trusts, at the point in time when the trust was established, Rautenbach was under sanctions by the United States and the European Union due to his ties to then-president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe. According to journalists, the donation had the effect of distancing Rautenbach from the business whilst retaining ultimate control.

In addition, they assert that the Bonsai Business Trust owned a non-tradable family investment fund listed on the Singapore Exchange, the White Orchid Fund, and that the main assets of the fund were inter-company loans (at very high interest rates between 8% and 20%) repayable by Rautenbach’s businesses in Zimbabwe. According to the journalists, the loan agreements “appear designed to strip cash, alternatively equity, out of the operating companies, effectively rendering operators, other creditors and minority shareholders completely hostage to Rautenbach’s offshore interests”.

Community trusts

The South African government has been using trust instruments to facilitate redressing societal inequalities. Despite their aim, there have been numerous court cases over the past several years over abuse and maladministration of so-called community trusts. Community trusts can fail to achieve their purpose due to a number of reasons: [43]

- failure to identify beneficiaries;

- external interference with trustees’ duties;

- stringent requirements of trust deeds; and

- insufficiently educated trustees.

Box 4. The Baloyi Commission [44]

The Baloyi Commission investigated how the Bakgatla ba Kgafela community was mistreated and how their rights to share in the benefits of mining were denied, publishing its report in 2019. The Bakgatla ba Kgafela are from Moruleng, in the province of North West, where platinum is mined. Their Chief, Nyalala Pilane, along with several members of the Bakgatla ba Kgafela Council, went against the community by making decisions without their consent.

By investigating community treasuries and their flow of money, the Baloyi Commission found that much of the mining operations’ wealth was reportedly used to profit offshore companies as well as Chief Nyalala Pilane and several local individuals.

The use of community trusts is particularly prevalent in the mining industry in order to comply with the provisions of the 2018 Mining Charter, which requires mining companies to divest benefits emanating from mining operations to surrounding communities. [45] There are countless examples of mining community trusts which have been maladministered and abused by those entrusted to ensure that the surrounding communities benefit. There are two factors attributing to the practical challenges of the success of these types of trusts. The first is the administration and oversight of trusts by the Master’s Office. The Master’s Office may be ill-equipped to focus on community trusts, their primary focus is the administration of deceased estates and the management of the Guardian’s Fund (the fund holding inheritance or assets on behalf of minors). Some have accused the Master’s Office of being “slow and bureaucratic”. [46] Secondly, communities are rarely involved or given insights into the matters of the trusts they are to benefit from, hindering the enforcement of their rights accordingly. Trustees often insert themselves as the community liaison and leverage such power for personal gain. [47]

Attorneys’ trusts

The law requires practising attorneys to open and operate a trust bank account with a reputable bank to hold funds in trusts on behalf of clients or third parties. [48] Such funds held in trusts do not form part of the attorney’s assets and, therefore, are not capable of attachment by creditors of the attorney. [49] An attorney’s trust account is created through means of a contract between attorney and client or through an escrow agreement to hold funds on behalf of a third party. The agreement will stipulate how, when, and under which circumstances the funds are to be invested, drawn down on, or, alternatively, transferred to a third party. In essence, an attorney’s trust account resembles a trust under the TPCA, but is regulated under separate legislation.

A 2022 study by the FIC states that the South African legal profession is potentially highly vulnerable to exploitation for money laundering and terrorism financing. [50] Attorneys offer their advisory services to clients, aiding them to create legal entities and arrangements, such as companies, trusts, or charitable foundations, as well as rendering conveyancing services relating to the transfer of property. [51] The report also flagged that in the event of certain types of litigation, fictitious debts can be created and claimed by moving illicit funds between parties and appearing to be a legitimate flow of funds. [52] Further, transactions facilitated through the attorney’s trust account – such as using cash or cryptocurrencies; the reversal of transactions with a request to repay funds advanced; and transactions that do not make economic sense – are all potentially high-risk transactions for facilitating money laundering activities. [53]

Therefore, the legal profession poses a threat as a facilitator for organised crime. Legal practitioners can be used to conceal proceeds of crime by obscuring the source of funds through trust accounts, and by setting up complex ownership structures and transactions in order to create distance between offenders and their illicit income or assets, obscuring beneficial ownership and complicating investigations conducted by law enforcement.

Box 5. Abuse of attorney trust accounts [54]

In one case documented by the FIC in 2018, attorneys’ trust accounts were used to purchase high-value assets for clients using the profits from illegal gold smuggling.

The FIC and the South African Police Service conducted an investigation into several individuals who were connected to multinational legal entities. By identifying and tracing the individuals’ bank accounts, financial transactions, assets, and foreign accounts, the FIC found suspicious deposits and withdrawals, as well as transfers to syndicate members from business to personal accounts.

In their analysis, the FIC found some of the individuals held offshore bank accounts and foreign properties, as well as attorneys purchasing properties and vehicles on the syndicate members’ behalf.

Ultimately, local law enforcement arrested the syndicate members and confiscated assets worth ZAR 6.8 million.

Endnotes

[38] See, for example: Pieter-Louis Myburgh, “Exposed: Zweli Mkhize’s R6m ‘cut’ from PIC’s R1.4bn deal using Unemployment Insurance Fund money”, Daily Maverick, 13 February 2022, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-02-13-exposed-zweli-mkhizes-r6m-cut-from-pics-r1-4bn-deal-using-unemployment-insurance-fund-money/.

[39] Financial Intelligence Centre (FIC), “Assessment of the inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks: Trust services providers’ sector”, March 2022, https://www.fic.gov.za/Documents/Trust%20Service%20Providers%20Sector%20Risk%20Assessment%20Report%20FINAL.pdf.

[40] Insights gathered from expert stakeholder interviews, May 2022.

[41] Insights gathered from expert stakeholder interviews, May 2022.

[42] Tebogo Tshwane, “Pandora Papers: Inside Zimbabwean tycoon Billy Rautenbach’s offshore family trust”, amaBhungane, 4 October 2021, https://amabhungane.org/stories/pandora-papers-inside-zimbabwean-tycoon-billy-rautenbachs-offshore-family-trust/; Tebogo Tshwane, “Pandora Papers: Inside Zimbabwean tycoon Billy Rautenbach’s offshore family trust”, Daily Maverick, 3 October 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-10-03-pandora-papers-inside-zimbabwean-tycoon-billy-rautenbachs-offshore-family-trust/.

[43] Olivier et al., Trust Law and Practice.

[44] Improving Transparency and Accountability in the Flow of Benefits to Mining Communities, Corruption Watch, 2021, 5, https://www.corruptionwatch.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/3727-CW-FLOW-OF-BENEFITS-MINE-COMM-REPORT-SPRD-LINKS.pdf.

[45] Improving Transparency and Accountability in the Flow of Benefits to Mining Communities, Corruption Watch.

[46] Improving Transparency and Accountability in the Flow of Benefits to Mining Communities, Corruption Watch.

[47] Improving Transparency and Accountability in the Flow of Benefits to Mining Communities, Corruption Watch.

[48] “Legal Practice Act 28 of 2014”, Section 86(2), https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/3802222-9act28of2014legalpracticeacta.pdf.

[49] “Legal Practice Act”, Section 88.

[50] Financial Intelligence Centre (FIC), “Assessment of the inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks: Legal practitioners”, March 2022, https://www.fic.gov.za/Documents/Legal%20practitioners%20Risk%20Assessment%20Report%20%20FINAL.pdf.

[51] FIC, “Assessment of the inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks: Legal practitioners”; A.J. Hamman and R.A. Koen, “Cave Pecuniam: Lawyers as Launderers”, Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal/Potchefstroomse Elektroniese Regsblad, 15, no. 5 (2012), https://doi.org/10.4314/pelj.v15i5.3.

[52] FIC, “Assessment of the inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks: Legal practitioners”.

[53] FIC, “Assessment of the inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks: Legal practitioners”.

[54] Financial Intelligence Centre (FIC), “Money Laundering Typologies and Indicators”, 2018, https://www.fic.gov.za/Documents/Money%20Laundering%20Typologies%20and%20Indicators.PDF.