An introduction to trusts in South Africa: A beneficial ownership perspective

Characteristics of trusts in South Africa

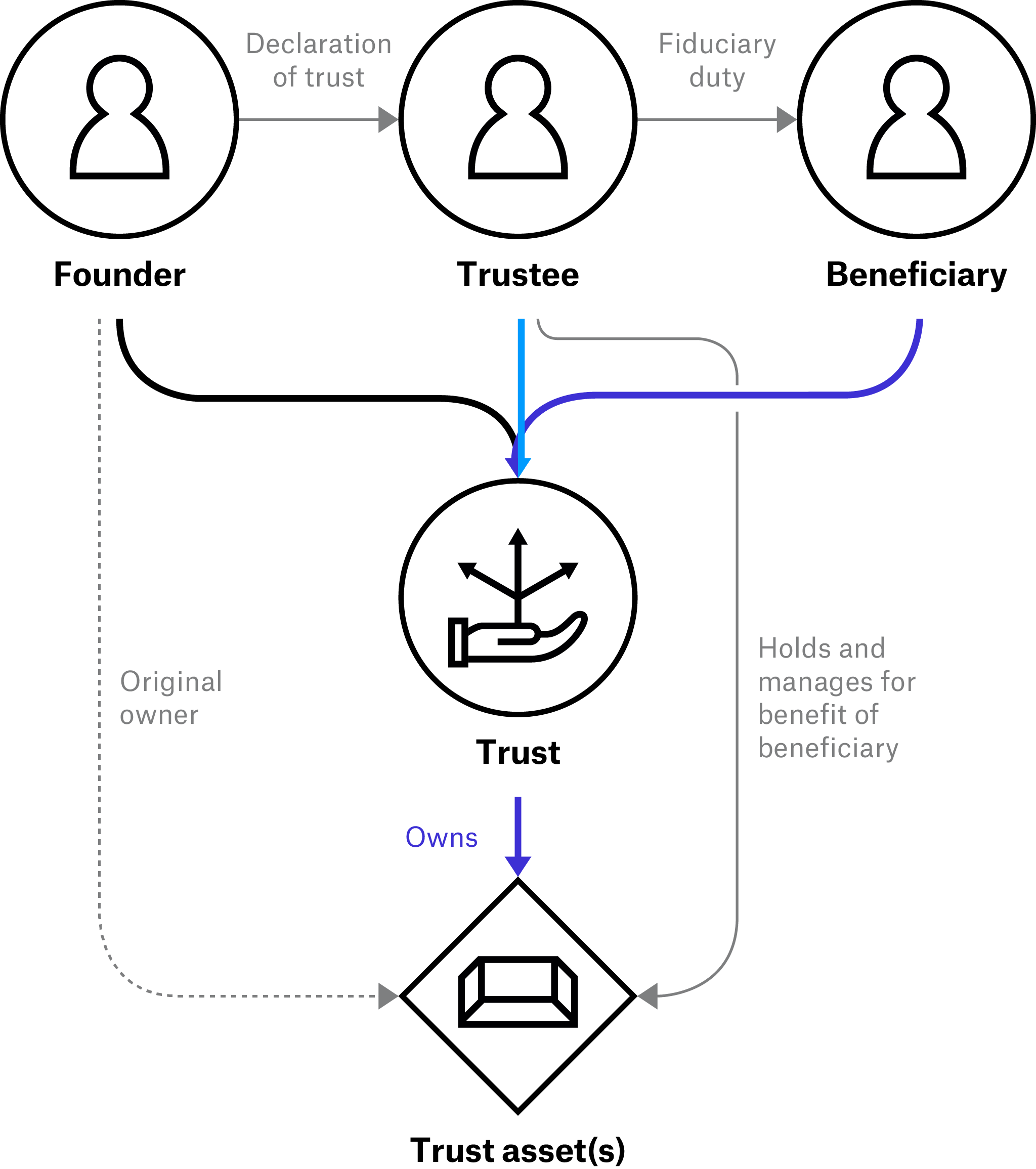

Trustees control the trust assets, and beneficiaries acquire full vested ownership in accordance with the provisions of the trust deed. [8] As a result, the question remains as to who ultimately benefits from, owns, or controls the trust assets for the duration of the trust instrument. According to most international standards, all parties to a trust are considered beneficial owners, including beneficiaries, irrespective of whether they have yet to benefit from the trust or not. At the time of writing, South Africa has no definition of the beneficial ownership for trusts, and it has no obligation for beneficial owners of trusts to be comprehensively identified and disclosed. GLAB includes amendments to the TPCA and contains provisions defining and requiring the disclosure of the beneficial ownership of trusts. At the time of writing, the Bill was still being considered by Parliament’s Finance Standing Committee, and its contents are not considered in this briefing.

Box 1. Elements of a trust in South Africa

- Parties to a trust [9]

- Founder(s): The founder is the individual or group of individuals (natural or legal persons) who creates the trust in order to express their intentions to convey property to a trustee for purposes of administration thereof for the benefit of beneficiaries. The founder, therefore, legally relinquishes their ownership of the trust asset(s).

- Trustee(s): A trustee is a natural person entrusted by the founder with the trust asset(s). A trustee is a signatory party to the trust deed and is responsible for managing the trust assets in accordance with the trust deed, read with the provisions of the TPCA. Trust assets, albeit legally held by the trustee under bare ownership, do not form part of the trustee’s personal estate. The trustee has a fiduciary duty to administer the trust to the benefit of the beneficiaries.

- Beneficiary(ies): Beneficiaries are either expressly named in the trust deed or ascertainable from the description and provisions set out in the trust deed. An example of ascertainable beneficiaries would be “all children of X, born or to be born, and all grandchildren of X”.

- Trust asset(s): The trust property constitutes the nucleus of the trust and can take the form of corporeal or incorporeal assets. Therefore, anything capable of being subjected to ownership and being liquidated into cash can be held by the trust. The trust assets have to be clearly identified or identifiable.

- Trust deed: The trust deed is a written record between the founder and the trustee(s) indicating which assets the founder bequeaths to the trust; who the beneficiaries are of the trust; and how the trustees are to administer the trust property. Prior to the trustee assuming control over the trust assets, they have to lodge the trust deed with the Master’s Office. [10] The TPCA requires trustees to furnish security deemed sufficient by the Master to ensure the due and faithful performance of their duties in terms of the trust deed, unless exempted from the same in accordance with the trust deed. [11] The validity of the trust deed is jeopardised when the founder is also the sole trustee and sole beneficiary of the trust, or if the beneficiaries are not identifiable in terms of the description.

Trusts are used for a range of lawful purposes, including for estate planning; to provide protection of assets from creditors; to hedge against currency devaluation and political uncertainty; to provide for the financial future of children; or to serve as a vehicle for overseas retirement funds. [12]

There are five essential characteristics for a trust to be valid according to South African law: [13]

- The founder must intend to create a trust, which means not merely using the trustees as contracting parties whilst the founder retains ultimate power and control over how the trust is managed. South African law does not, thus, allow self-interested and self-directed trusts; even though a founder can be a trustee, they can never be a sole trustee.

- The founder must intend to create a trust that places a legal obligation on the trustees to manage the trust object, either through a will, contract, or trust deed.

- The subject matter of the trust must be able to be defined with reasonable certainty.

- The objective of the trust must be able to be defined with reasonable certainty.

- The objective of the trust must not be illegal.

In South African law, a trust is a sui generis legal arrangement in that it does not have a legal personality. This, essentially, means that the trustee obtains only bare ownership of the trust asset(s): thus, the trust assets do not form part of the trustee’s personal estate, and the trustee does not have an automatic right to the use and benefit of the rights to the trust assets. [14] This principle is further recognised by the South African Revenue Services (SARS), identifying trustee(s) as being the holder of the ownership of the trust assets in only a fiduciary capacity. Therefore, trusts have to file their own income taxes through the trustee(s) as the representative taxpayers. In the context of BOT, this often results in perceived “ownership limbo” of trusts: the assets no longer belong to the founder, but they do not belong to the trustee(s), and they do not yet belong to the beneficiaries. The trustee has the obligation to manage and administer the assets of the trust to the benefit of the beneficiaries identified in the trust deed, in accordance with the powers and duties conferred to the trustee in terms of the trust deed and section 57 of the TPCA. In addition, trustees may be granted discretionary powers in the trust instrument to identify beneficiaries from a prescribed group subject to certain criteria. This can create ambiguity as to who ultimately is entitled to receive the benefits under the trust.

Despite a relatively clear understanding in South African jurisprudence of the roles of the different parties to a trust, there is less clarity about the legal nature of trusts. The result of this uncertainty is that there is a significant discrepancy between the legal theory of trusts and the practical application of trusts. [15] In theory, trusts are not legal persons with a separate legal personality like a company would have, but they are often treated as such in practice. [16] There is also no uniform acceptance in South African law about who the subject of the trust is. [17] As a result, identifying the beneficial owner of a trust is not straightforward in law nor in practice.

Endnotes

[8] BDO Wealth Advisory, “Trusts”, BDO, 2016, https://www.bdo.co.za/getmedia/1ed18ab6-f01e-4a62-83f2-ce1d315d8898/bdo-trust.

[9] Many trust law countries include the role of “protector” as a party to a trust, however, protectors do not exist in South African trust law. Nevertheless, it is important to be aware of the role of protectors, as foreign trusts owning assets in South Africa may have protectors.

[10] “Trust and Property Control Act (TPCA) 57 of 1988”, Section 4(1), https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201505/act-57-1988_0.pdf.

[11] “TPCA”, Section 6.

[12] A.W. Oguttu, “International Tax Law: Offshore Tax Avoidance in South Africa”, 2015.

[13] If any single one of these characteristics is not present, the trust will be deemed invalid. The challenge, however, is that tax haven trusts do not require the presence of these characteristics in all cases, which allows for the creation of off-shore trusts that would be deemed sham trusts in South Africa. See: Edwin Cameron, Marius de Waal, Basil Wunsh, Peter Solomon, and Ellison Kahn, Honore’s South African Law of Trusts (South Africa: Juta Law, 2002).

[14] “TPCA”, Section 12.

[15] Olivier et al., Trust Law and Practice.

[16] For example, trusts are treated like legal persons in contractual relations, various aspects of taxation, and estate planning, despite the theoretical assertion that trusts are not legal persons. See: Olivier et al., Trust Law and Practice.

[17] Olivier et al., Trust Law and Practice.