Defining and capturing data on the ownership and control of state-owned enterprises

Defining state-owned enterprises

The OECD defines an SOE as being “under the control of the state, either by the state being the ultimate beneficial owner of the majority of voting shares or otherwise exercising an equivalent degree of control”. [6]

The EITI defines an SOE as a wholly or majority (50%+1 share [7]) government-owned company that is engaged in extractive activities on behalf of the government.

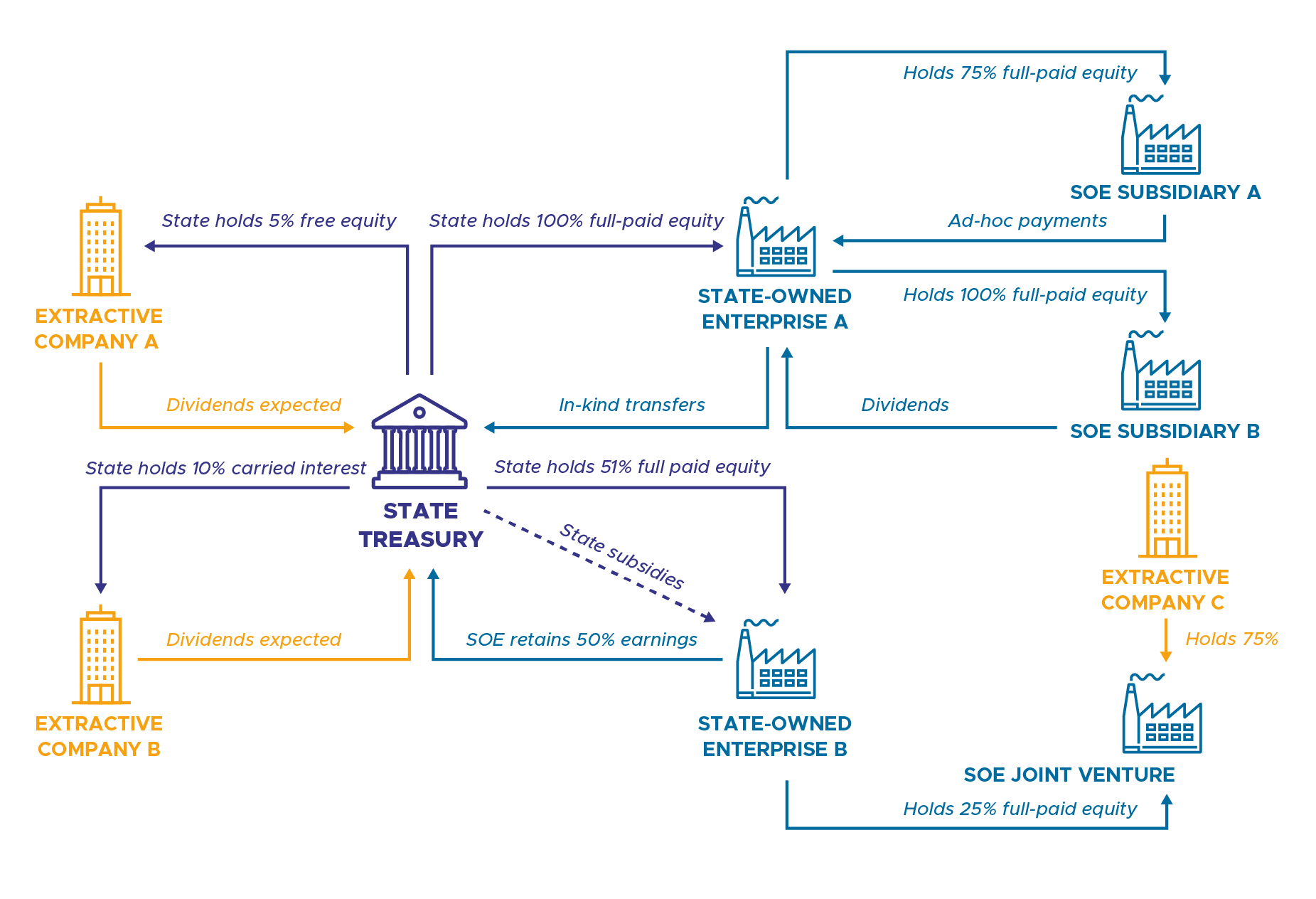

State participation in the extractive industries: Mapping the fiscal relationship between the state and the extractives communities

Source: EITI [8]

SOEs often have complex corporate structures – sometimes spread across multiple jurisdictions – which intertwine with governments in diverse ways via direct or indirect ownership stakes or controlling interests.

A state can be a minority owner and still exercise significant influence and control over a company or an SOE

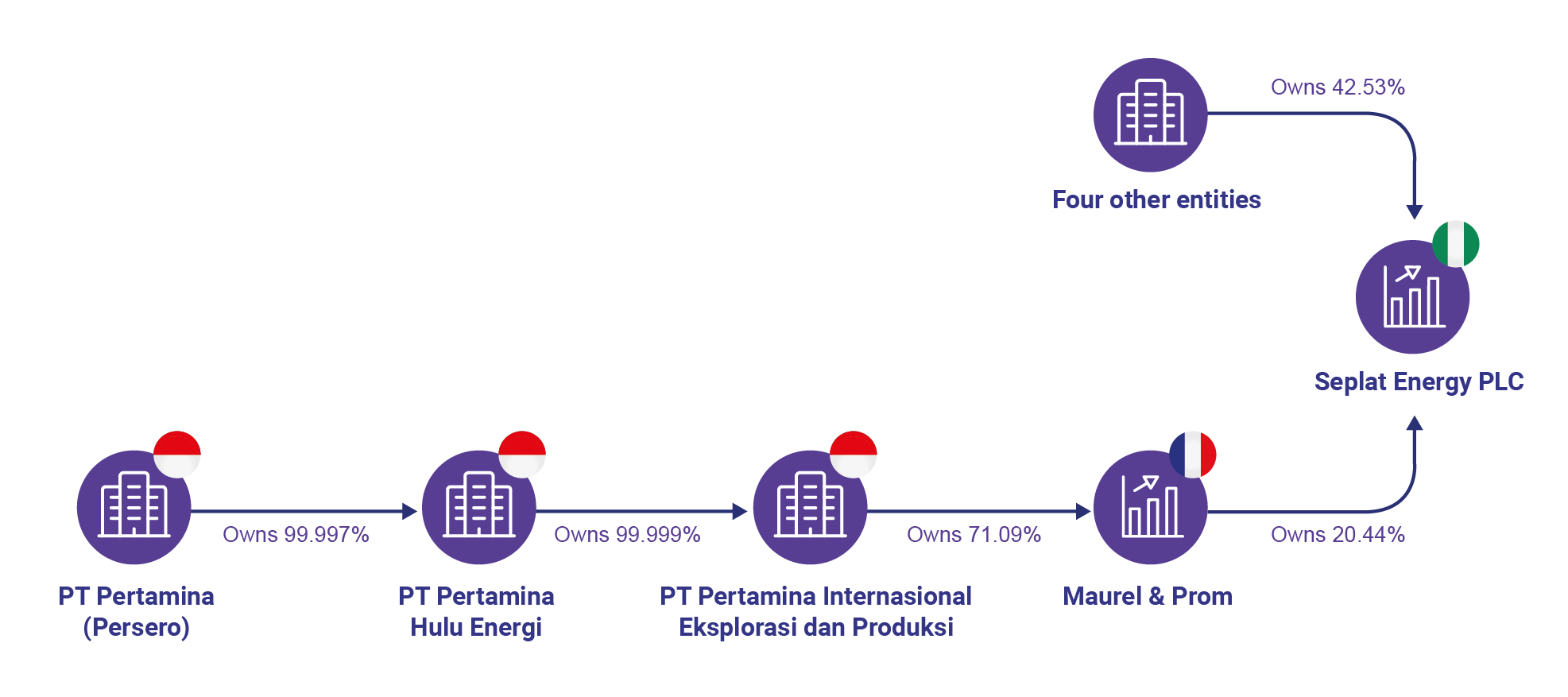

Visualising elements of the ownership and control of Pertamina using structured data

The diagram above shows the Indonesian SOE Pertamina and one arm of its subsidiaries and associates. Pertamina owns a majority shareholding of 71.09% [9] in Maurel & Prom. It, in turn, is the largest single shareholder in the publicly listed Nigerian oil and gas company Seplat Energy PLC, with a 20.44% stake.

This example illustrates some of the considerations that would need to be taken into account by various parties in their beneficial ownership regimes, for instance:

- The Nigerian government may wish to ensure that foreign state interests, such as that of Pertamina, fall within their beneficial ownership disclosure regime.

- The French government may wish to ensure that Pertamina’s ownership interest is declared by Maurel & Prom.

In Indonesia, to be considered an SOE, at least 51% of shares must be directly owned by the state. [10] By setting a definition with a threshold as high as 51% and requiring direct government ownership, Indonesia’s list of SOEs will exclude companies, such as Maurel & Prom, where the government has substantial ownership or control stakes, albeit indirectly or just below a majority. This makes it more difficult to get a holistic picture of state ownership globally, hindering transparency and anti-corruption initiatives.

By over-relying on ownership mechanisms, such as shares, there is a risk of excluding SOEs that are controlled by the state in other ways. It is common for legislation to set out additional rights, such as appointing both executive and non-executive positions, and companies themselves may have clauses in their articles affecting control.

With reference to Maurel & Prom, shares held for more than four years, without interruption, confer a double voting right. [11] While this clause is not exclusive to SOEs, it highlights the complexity of control mechanisms. Clauses like this can result in changes in beneficial ownership without changes in shareholdings, and where such shares are held by government, such rights could potentially result in a company falling under the definition of an SOE.

When defining an SOE, consideration should be given to the following:

- Shareholdings and thresholds

- Direct and indirect ownership and control

- Foreign entities, states and interests

Endnotes

[6] OECD (2022), Recommendation of the Council on Guidelines on Anti-Corruption and Integrity in State-Owned Enterprises. OECD/LEGAL/0451. Retrieved from https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0451.

[7] EITI (2020), EITI Requirement 2.6 – State participation and state-owned enterprises: Guidance Note, 6. Retrieved from https://eiti.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/en_eiti_gn_2.6.pdf.

[8] EITI, EITI Requirement 2.6 – State participation and state-owned enterprises: Guidance Note.

[9] Maurel & Prom (2022), 2021 Universal Registration Document : Including the Annual Financial Report, 202. Retrieved from https://www.maureletprom.fr/en/documents/download/1343/2021-universal-registration-document.

[10] Presiden Republik Indonesia (n.d.), Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 19 Tahun 2003 Tentang Badan Usaha Milik Negara, Chapter 1, General Requirements, Article 1, 2-3. Retrieved from https://peraturan.go.id/common/dokumen/ln/2003/UU0192003.pdf.

[11] Maurel & Prom, 2021 Universal Registration Document : Including the Annual Financial Report, 201.

Next page: Ensuring comprehensive coverage of state-owned enterprises