Early impacts of public beneficial ownership registers: United Kingdom

Case Study: The Beirut explosion

Damage after the Beirut explosion, Mehr News Agency, CC BY 4.0

On 4 August 2020, there was an explosion in a warehouse in the port of Beirut. Described as “one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history”, it resulted in the deaths of 211 people, injured 5,000 and made over 300,000 people homeless.[19] The explosion is estimated to have caused collective losses of USD 10-15 billion.[20] It was caused by the detonation of 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate that was stored unsafely at the warehouse in the port of Beirut. The ammonium nitrate had arrived in Beirut in September 2013 on the MV Rhosus, a Moldavian flagged ship bound for Mozambique, owned by a Panamanian company.[21] The ship was forced to stop in Beirut after an inspection from the Beirut port authorities. It had remained in the port since, effectively abandoned, with a number of creditors making claims for payment against the ship, and the port authorities failing to contact the owners.[22]

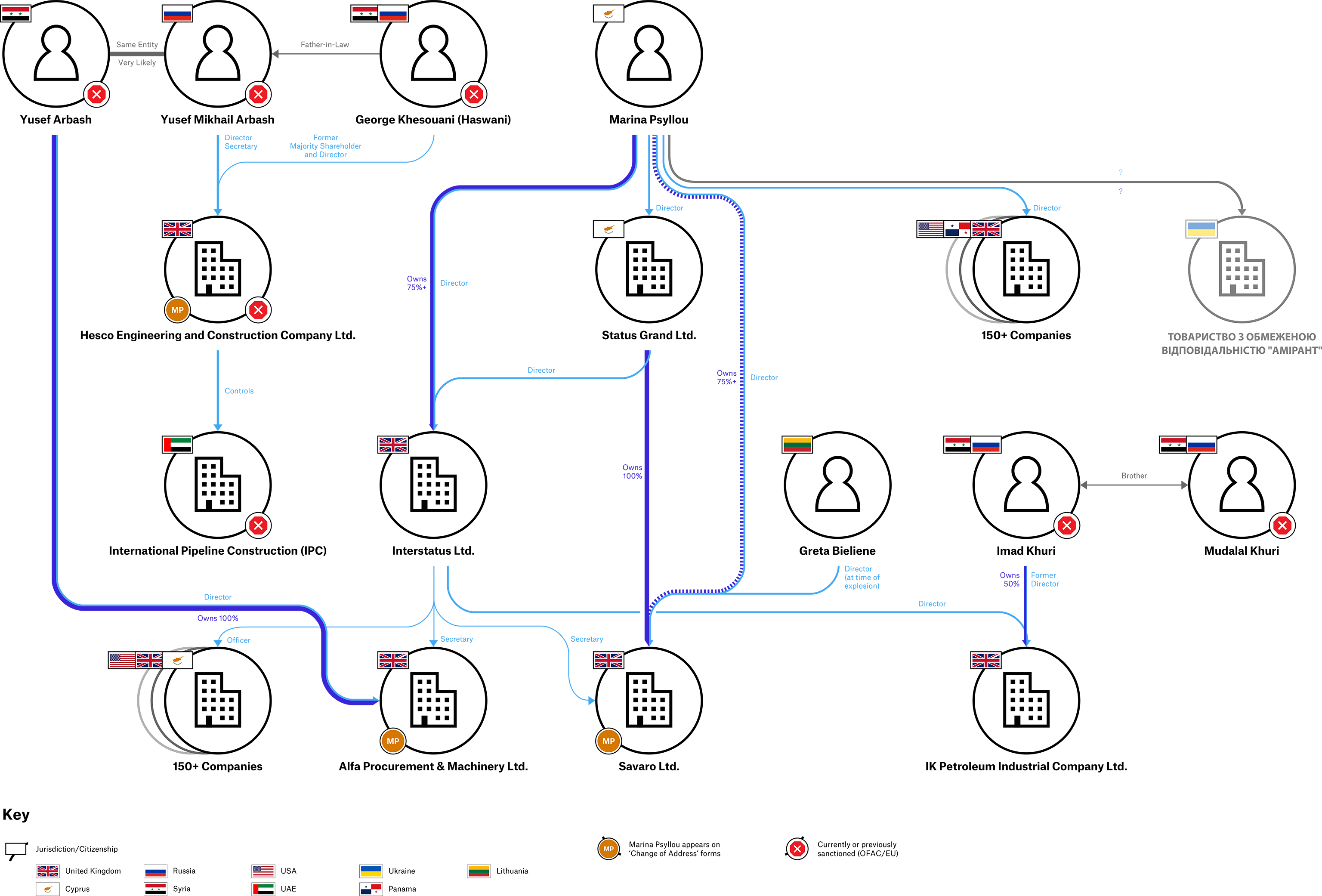

Following the explosion, financial crime investigators Graham Barrow and Ray Blake sought to understand the people behind the abandoned ship and its cargo.[b] Using data from the UK PSC register and Ukrainian data, accessed through the OO register, the investigators were able to trace direct links between the UK registered company that bought the ammonium nitrate, Savaro Ltd, to a number of other companies and sanctioned individuals through the company’s registered beneficial owner. Data from the UK PSC register also showed that Savaro Ltd shared the same UK address with two other companies, both with links to two businessmen who were sanctioned for ties to the Syrian regime.[23] All three companies changed their address and the location of their registers on the same day, and the name and signature of Savaro Ltd’s beneficial owner appears on all three change of address forms. Although this does not prove a connection between the companies or necessarily indicate any wrongdoing, it does suggest a link that helped further the investigation.

Figure 1. Ownership structure and beneficial owners of Savaro Ltd.

Sources: The diagram above has been compiled from the following public sources to illustrate the complexity in understanding ownership structures based on limited publicly available information: Open Ownership Register; Companies House register; US Treasury; The Dark Money Files podcast “British Shells and the Beirut Blast” and accompanying article. The information contained in this diagram is compiled on a best efforts basis and is not exhaustive or complete. Aspects of the ownership structure have been left out where the information is not available, not relevant to illustrate the story, or challenging to visually represent. The diagram covers multiple time periods, rather than a snapshot. Not all of the entities and officers shown are still active.

After identifying the name of the company that had purchased the chemicals, Savaro Ltd,[24] independent financial crime investigators were able to use UK PSC register data on the OO register to identify links between the beneficial owner of that company and other companies. This analysis was possible because the UK PSC data was available in machine-readable format, which could be ingested to the OO register to easily show the beneficial owner’s links to other companies.[25]

Because the OO register ingests data from multiple registers, the data also revealed links to a company in Ukraine. The investigation is ongoing. Whilst none of the above implies wrongdoing by any of the companies or persons mentioned, the case clearly demonstrates the value of BOT in at least identifying the persons responsible for the ship’s dangerous cargo.

Footnotes

[b] Please listen to the Dark Money Files podcast for the full story: Graham Barrow and Ray Blake, “British Shells and the Beirut Blast”, The Dark Money Files podcast, 17 January 2021, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/british-shells-and-the-beirut-blast/id1448635132?i=1000505495826.

Endnotes

[19] Associated Press, “‘Not Like Every Time:’ Beirut Blast Victims Want the Truth”, Voices of America (VOA), 6 February 2021, https://www.voanews.com/middle-east/not-every-time-beirut-blast-victims-want-truth.

[20] “Beirut Explosion: What We Know So Far”, BBC, 11 August 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-53668493.

[21] Felipe Arizon, “The Arrest News: 11”, Shiparrested.com, October 2015, https://shiparrested.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/The-Arrest-News-11th-issue.pdf.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Martin Chulov, “Businessmen with ties to Assad linked to Beirut port blast cargo”,The Guardian, 15 January 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/15/businessmen-with-ties-to-assad-linked-to-beirut-port-blast-cargo.

[24] “Savaro Limited”, Open Ownership Register, n.d. https://register.openownership.org/entities/59b9646967e4ebf34020086d.

[25] “Marina Psyllou”, Open Ownership Register, n.d., https://register.openownership.org/entities/59b9646967e4ebf34020088e.

Next page: Case Study: Linking politically exposed persons to UK assets