Making central beneficial ownership registers public

Overview

The question of whether data should be made open and accessible to the public, and the concerns about personal privacy and security risks to individuals, are some of the most debated issues in beneficial ownership (BO) reform. These are important, connected issues that need careful consideration by implementers. As beneficial ownership transparency (BOT) is a relatively new policy area, there is not yet a large body of evidence on the impact of making registers public. Nevertheless, where public registers have been implemented, early evidence is emerging and specific benefits of making BO data publicly available can be identified.

The publication and public access to certain personal data, such as electoral registers [1] and building permits [2], is long established and is, for the most part, considered to be uncontroversial. The publication of BO data, however, has raised significant concerns over privacy. Some have questioned its proportionality to achieving certain policy aims, stating, for instance, that most business owners have nothing to do with financial crime. Others raise concerns over risks to personal safety. This is despite the fact that in many places, shareholder data is already publicly accessible (sometimes against a small fee) meaning BOT reforms would only affect individuals involved in more complex, and potentially suspicious, ownership structures. At the same time, no examples of serious harms that have arisen from the publication of BO data in open registers have been documented.[3]

Over 100 jurisdictions have committed to implementing BOT reforms, and over 40 of those committed in 2020.[4] These reforms are taking place in a global context where data about people is created online every day, at a rate which many regulators are still grappling with. In the EU, for example, the directive that obligated all member states to make their BO registers public, the fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD5), was passed in the same year that the EU’s most extensive data protection legislation to date, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), became enforceable. A few court cases against the publication of personal data in BO registers on the grounds of GDPR have followed. It is important that this is being tested in the courts, and their outcomes will no doubt have a profound impact on the debate. In other countries, such as Mexico, there are concerns for kidnapping and personal safety. These need to be assessed and understood.

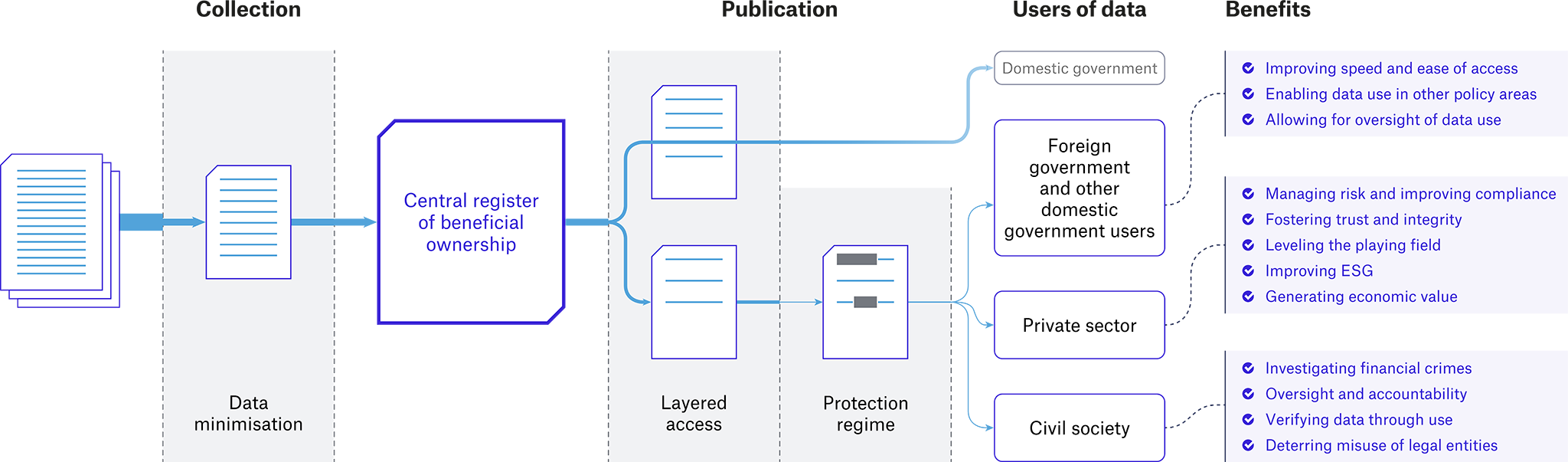

The publication of any data, personal or otherwise, as part of BO disclosures has some known consequences as well as some potentially unknown consequences. BO data is different from many other datasets being made open, such as contracting data, as it must contain personally identifiable information to be useful and achieve its purpose. Implementers and transparency advocates should not advocate for information to be made public without carefully considering the potential risks, and how these can be mitigated in specific contexts. Consequently, this policy briefing does not take the position that making BO registers public is a goal that all jurisdictions must pursue in and of itself. Rather, it outlines the benefits that arise from making a BO register public by looking at how different user groups are able to use the data when it is made public, and identifying the benefits this has.

For government users, benefits include:

- improving speed and ease of access for existing government users;

- enabling data to be used in additional policy areas;

- allowing for oversight of data use.

For private sector users, benefits include:

- managing risk and improving compliance with government regulations;

- fostering trust in the integrity of the business environment;

- leveling the playing field between companies;

- improving environmental and social governance (ESG);

- generating economic value from data reuse.

For civil society users, benefits include:

- carrying out investigations into financial crimes and corruption;

- allowing for oversight and holding government to account;

- verifying data through use;

- deterring misuse of legal entities.

This briefing argues that there is sufficient evidence for it to be reasonable and rational for policymakers to act on the understanding that a public register will serve the public interest. As most public registers have been implemented in Europe, most examples are taken from European countries. Nevertheless, the benefits are also applicable to other contexts. Potential negative effects will differ per jurisdiction and need to be properly understood.

The briefing then outlines and analyses different considerations for implementers, such as:

- collating BO data centrally;

- making data available as structured, open data: accessible and usable without barriers such as payment, identification, registration requirements, collection of data about users of the register, or restrictive licensing, and searchable by both company and beneficial owner;

- establishing a legal basis and defining broad a purpose for publishing data, in keeping with data protection and privacy laws;

- mitigating potential negative effects of publication by:

- limiting the information collected to what is strictly necessary (data minimisation);

- making a smaller subset available to the public than to domestic authorities, omitting data fields that are particularly sensitive and unnecessary to generating the benefits (layered access);

- implementing a protection regime that allows for exemptions to publication in circumstances where someone is exposed to disproportionate risks.

The starting point for all BOT reforms should be the policy aims governments want to achieve.[a] To what extent making data public is reasonable, proportionate, and justified will differ per policy area. BOT, when implemented well, can serve a wide range of policy aims. The more policy aims BOT serves, the greater the benefits to society. Therefore, this briefing will take a holistic approach and focus on data use and user groups, whilst referring to individual policy aims.

Figure 1. Maximising benefits and mitigating potential negative effects of making central BO registers public

Making BO registers public provides access to government, private sector and civil society user groups that generate a range of benefits contributing to various policy areas.

When making BO registers public, governments should:

- collate BO data centrally;

- make data accessible and usable;

- establish a well-founded legal basis;

- mitigate potential negative effects by:

- adhering to the principle of data minimisation

- implementing a system of layered access

- implementing a protection regime

Footnote

[a] Common aims include fighting money laundering, financial crimes, and corruption, as well as attracting (foreign) investment. An increasing number of governments are also pursuing BOT reforms for oversight and accountability in procurement, and AMLD5 specifically mentions preserving trust in the integrity of business transactions and the financial system.

Endnotes

[1] “National Voters’ Service Portal”, Election Commission of India, n.d., https://electoralsearch.in.

[2] “Historical DOB Permit Issuance”, NYC Open Data, 8 February 2020, https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Housing-Development/Historical-DOB-Permit-Issuance/bty7-2jhb.

[3] “Privacy or public interest? Making the case for public information on company ownership”, The B Team, The Engine Room, and Open Ownership, March 2019, 4, https://www.openownership.org/uploads/privacyreport-summary.pdf.

[4] “Worldwide commitments and action”, Open Ownership, n.d., https://www.openownership.org/map/.