Merging and de-duplicating beneficial ownership data

Welcome to the third in a series of technical posts about working with beneficial ownership (BO) data. Over the past three years, Open Ownership (OO) has been building a prototype Global Beneficial Ownership Register, in order to prove the feasibility and value of linking BO data across jurisdictions. We have used this project to experiment with a variety of tools and processes, from standardising data under the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS) to providing a search engine, disclosure viewer, data archive, and network visualisation (amongst others). As this phase of our work draws to a close, we are documenting the things we have learned and sharing our experiences with data users and publishers in the public and private sector.

In Parts One and Two, we covered the broad topic of modelling BO data, then the significant challenge of reconciling data from different sources. This blog post expands on reconciliation to discuss the related subject of finding duplicated data and merging records. We will cover the modelling approaches needed to make merging possible and, crucially, reversible; different strategies one can adopt to find duplicates; and finally, what publishers can do to make duplicates less likely.

Why do we need to merge duplicates?

In a perfect world, where every BO record can be reconciled through unique identifiers, we would not have any duplicated data. Of course, the world is not perfect and in many disclosure regimes unique identifiers are not available, particularly for people. This ultimately results in less valuable data, because one of the most common questions asked of BO data is “what does this person own?” When a person’s records are duplicated, that question is not trivial to answer.

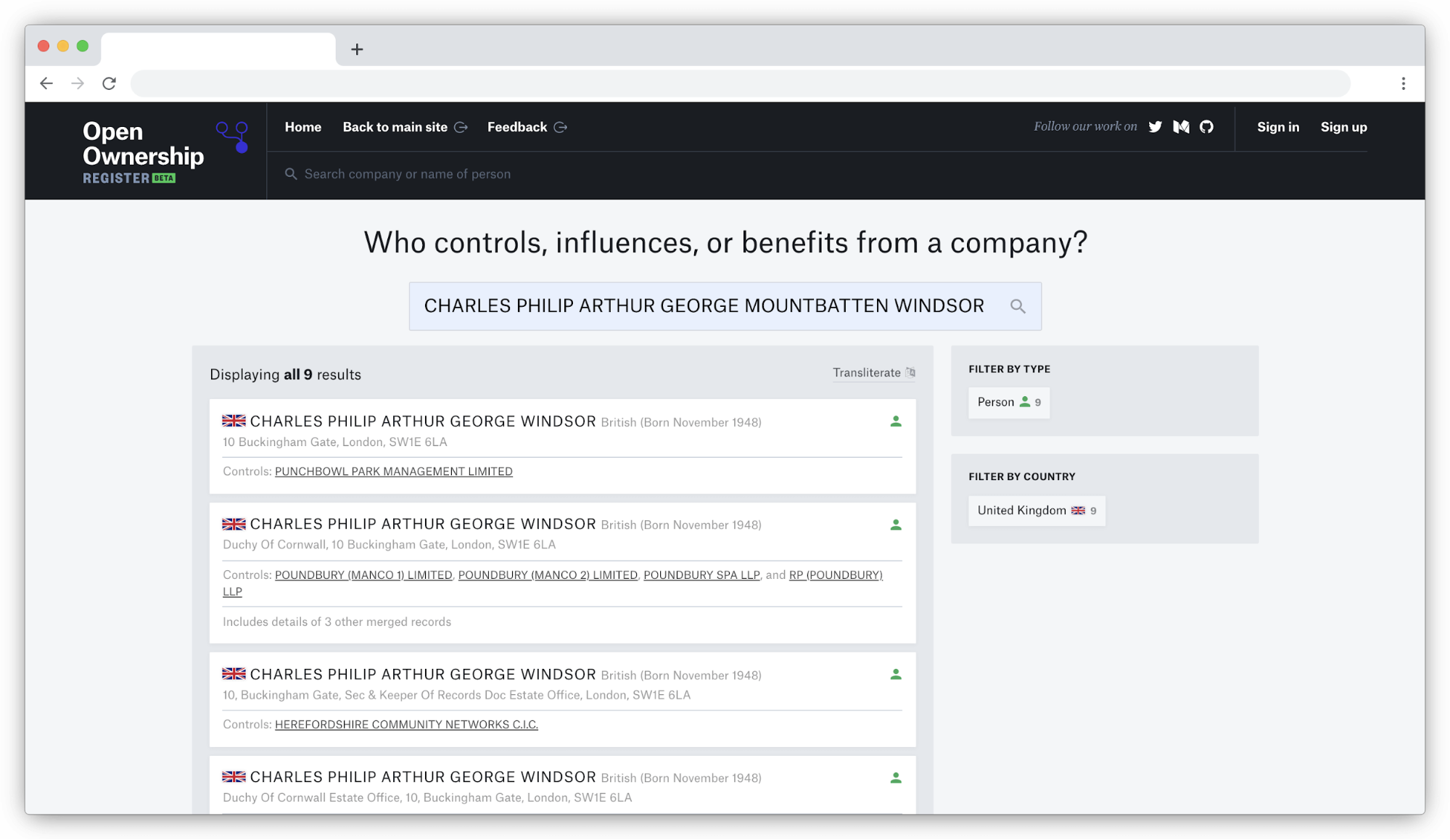

Here is an illustrative example from the UK’s Persons of Significant Control register:

Screenshot of the Open Ownership Register showing multiple search results for the UK’s heir to the throne: Prince Charles

Despite his uniqueness as heir to the British throne, the nature of the UK’s BO reporting means that it is impossible to know for sure that the 17 different records returned for Prince Charles refer to the same person. Each ownership is reported separately by the company involved and there is no uniquely identifying information across them which can link Prince Charles definitively.

This is not just a problem unique to people, or to the UK. Across other data sources we import into the register, there are many other situations that also require deduplication, for example:

- when data is unstructured, requiring information to be extracted from free text, as in Ukraine’s Unified State Register;

- when dealing with companies without knowing in which jurisdiction they are registered, as with non-Slovakian companies in the Slovakian Public Sector Partners Register;

- whenever registers record transliterated versions of names according to different standards, and/or when registers do not record the original version of the name.

Eagle-eyed viewers will notice in the screenshot above that the Open Ownership Register has succeeded in merging some records. It has achieved this by matching them exactly on the name, date of birth, and address. However, even with a name as regal as Charles Philip Arthur George Mountbatten Windsor, one sees a lot of variation. The register takes a particularly conservative approach, requiring exact matches across every field in an attempt to limit any mismatches. Other applications might prefer to be less strict, but no deduplication strategy will be perfect; it naturally reflects the risk appetite of the data’s end users. As a project with a small budget for corrections and a wide audience, we would rather not be wrong.

Strategies

Many of the technical strategies for deduplication look similar to those discussed with regards to reconciliation in Part Two of this series. The difference is that users are not relying on some external oracle to identify the data, but rather looking within their own data to find likely matches. Similar techniques of data normalisation can increase that likelihood, so tools like Open Corporates and libpostal as well as simple text trimming and formatting can all help. We introduced and discussed a lot of these broad concepts in our earlier post, so here we are going to take a deeper dive into two tools to help put these approaches into practice.

Elasticsearch or other search engines

With any complex matching system, users will be dealing with heuristics to find matches and searching across all of their data. This is basically a perfect situation for a search engine. On the Open Ownership Register we use Elasticsearch to power our search functions, so it made sense for us to use it to power duplicate matching, too. There are other search engines available that have similar features, and can give equally good results.

The basic approach is to set up a new index specifically for duplicate finding. In it, normalised versions of all the fields from the data that are useful to the matching process should be added: names, addresses, dates of birth, etc. Elasticsearch has a powerful system for things like standardising cases, alternate versions, etc., that can be used to help with this. Specialised queries can then be used with the full power of the search query engine to find duplicates for each record. In addition to being extremely flexible (and potentially very fast), this will automatically give users a scoring system for the results it finds.

The key to success in this setup is defining the search query precisely and then preparing the data in the index to make searches fast. A simple search for a name amongst all the data will likely return lots of results, and it will be difficult to discriminate between them. The chosen search engine’s query language should be experimented with, and a combination of fuzzier searches on specific fields with exact matches on others should be used. At the outset, some of these combinations will be expensive to run, but once a clear approach has been found, users can optimise their search index to speed them up.

Dedupe.io

An alternative to a hand-tuned heuristics based search engine is a machine learning approach. Dedupe.io is an example of this, available as self-hosted software or as a hosted service, where users “train” a model by giving it examples of duplicates and allow their algorithms to work out from those examples which characteristics of the data connect duplicates. Dedupe.io has some extremely detailed documentation, which explains not only how they calculate matches, but also how they make the matching process performant across large datasets. This is recommended reading for anyone interested in de-duping, regardless of whether or not their service is being used.

Modelling for errors

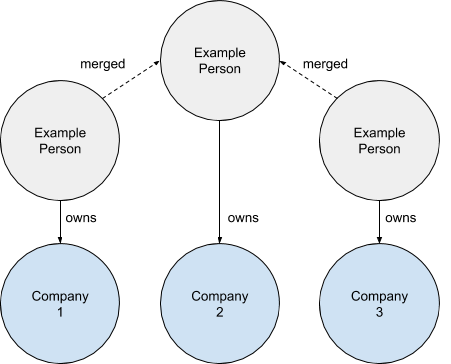

No matter how clever a matching algorithm is, there will always be mistakes to deal with. Therefore, how the merging aspect of a deduplication system is implemented is extremely important. In the Open Ownership Register, we refer to two kinds of merges: hard and soft. Hard merges leave no trace: there is no way to undo them. Soft merges are where two records are functionally merged, but that merging process can be undone at a later date. We achieve this by modelling a merge as another connection in a graph:

Diagram showing three individual ownership records connected by new links between duplicate people

Technically, this is achieved in our database by adding another relationship between the merged people. We pick the person record with the most owned companies and then link the others to it. Then, within our application code, we enforce the primacy of that record during all interactions with it or any of the other merged records. Crucially, this design allows us to connect those secondary records to a new primary, should any error come to light. The Open Ownership Register does not do this yet, but a more generalised form of this approach would allow a system to present multiple interpretations of merged data, with different connections for different algorithms used to match records.

The second key consideration of this process, especially when running deduping automatically, is to be able to monitor what is happening and, in particular, to alert when data indicates that previous merges are no longer accurate. In the data model explained by the diagram above, any time a record’s primary, or status as a primary, changes, that is an indication that some new information has come to light. Alerting on every change might produce so many alert that systems might want to guard against such changes in normal usage and then run separate error-finding processes to check regularly. The Open Ownership Register manages this by logging instances of changes during the process and then reviewing them periodically, but our de-duplications are run manually and sporadically so that we can dedicate time to this analysis.

The final key component to merging duplicates is providing transparency into what has happened to end users of a system: explaining first that merging has happened, using what algorithm/criteria, and then, ideally, allowing users to see the original records that were merged.

What can publishers do?

Our work at Open Ownership speaks to both users of data and publishers. When we talk about duplicates or merging records, often we are fixing issues that could have been solved by the original publishers of that data. However, the scope of what a publisher could possibly do and what they can feasibly do within their current disclosure regime often vary hugely. Below are some of our most pragmatic suggestions, in a roughly ascending order of complexity:

- Publish data in a standardised, structured format such as our own BODS. Ideally, this will allow data users to start with data that is as high quality as a publisher has internally.

- Make sure truly unique identifiers are being captured. For example, if you are asking for registration numbers from foreign companies, record the specific register they are from as well.

- When recording names, record them both in their original form and transliterated to the official language(s) of the register. Ask the submitter of the information to do this themselves, or do it according to a published standard (and document what standard that is).

- Verify submitted addresses against a government database (if one exists) and publish the standardised form of the address from that database. If no such database exists, verify that the address exists by sending a verification code in the post, which submitters must enter.

- If people or companies do not have an existing unique identifier that can be used, give them one which is at least unique within the BO disclosure system.

Summary

Overall, deduplication is a chore that all who work with BO data in the real world will have to deal with. There are some great high-tech solutions that can be put to work, but ultimately one of our aims at Open Ownership is to make them less necessary. Through our work on the BODS and our principles for effective BO disclosure we hope to increase the quality of BO data around the world, and reducing duplicates is one key measure.

Key findings:

- de-duplication is a heuristic based process that will never be 100% correct. Experiment with your approach on data that you know and be prepared to iterate on your algorithms;

- model your data so that you can change merges in the future when new data comes to light;

- ensure transparency in processes and ideally have a continuous process for monitoring duplicates and merges;

- help us solve the problem at the root by pushing publishers to make changes that reduce duplicates when data enters their registers.

Related articles and publications

Publication type

Blog post

Topics

Beneficial Ownership Data Standard,

Open Ownership Register

Sections

Technology

Open Ownership Principles

Structured data