A first (quick) look at the verification mechanism of the new UK Register of Overseas Entities

An Open Ownership long read

What is the Register of Overseas Entities?

The Register of Overseas Entities (ROE) came into force in the UK on 1 August 2022 through the new Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Act 2022 (ECTEA). The register applies to overseas entities that want to buy, sell or transfer property or land in the UK, and will also apply retrospectively to varying degrees in England and Wales, and Scotland. These entities must register with the UK company registrar – Companies House (CH) – and disclose their “registrable beneficial owners”. ECTEA’s passage through parliament in March 2022 was expedited in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, to enable the UK Government to more effectively enforce sanctions.

As in 2016, when the UK was one of the first countries to implement a register of beneficial ownership (BO) for domestic legal entities, it is charting new territory with these measures. Open Ownership (OO) expects that more countries will follow suit following revisions to the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) Recommendation 24, approved in March 2022. Countries will now be required to collect BO information on foreign entities which have a “sufficient link” to the jurisdiction, with the ownership of real estate mentioned as an example. However, being among the first to implement a BO register had the clear disadvantage that the UK could not build on lessons learned from established practice. In 2016, civil society organisations – including OO – identified a number of issues with the UK register, some of which were subsequently addressed by CH. It is anticipated that CH will address other issues regarding the verification of domestic entities later in 2022.

There will be many lessons to learn once more data is published online: at the time of writing, just 40 overseas entities are listed on the register. For now, as the subject of verification – especially that of foreign entities – remains a challenge for many implementers, OO has had an initial look at the verification mechanism in ROE. Although weaknesses have been identified, CH has a commendable history of constructive stakeholder engagement and communication. In any case, other jurisdictions will be grateful for any lessons that can be learned from the UK example.

This rapid analysis focuses on ROE’s verification approach. Other aspects of the disclosure regime – such as definitions – are outside of its scope. It is based on the guidance for registration, technical guidance for registration and verification, and forms published by CH, and the statutory instrument. As this analysis is only based on publicly-available information, there may be some inaccuracies. Any assumptions made by OO in this analysis are noted.

ROE’s verification mechanism

In a recent briefing on sanctions and enforcement, OO recommends requiring the submission of BO declarations for foreign entities through domestically regulated entities. OO also recommends countries place responsibility on these domestically regulated entities to verify the information and impose relevant sanctions for noncompliance. This is to create liability domestically, over a legal person that the country has jurisdiction over. Slovakia piloted verification by domestically regulated entities for its procurement register. The UK has also taken this approach for ROE, where verification is now a precondition for buying new property.

Who can verify?

Overseas entities must have their BO information verified by a UK-based and supervised “relevant person” under the Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing and Transfer of Funds Regulations 2017 (MLRs). A UK-regulated agent must complete verification checks on all beneficial owners and managing officers of an overseas entity and submit this within 14 days of specified “relevant activities”, including: registration, annual updates and submitting an application for removal. An agent can be an individual, such as a legal professional, or a corporate entity (i.e. an employer of an agent or multiple agents), such as a financial institution. Not all relevant persons are permitted to verify BO information (e.g. casinos). They may also not be family members or known close associates of the beneficial owners, or the beneficial owners themselves.

What is needed for verification checks?

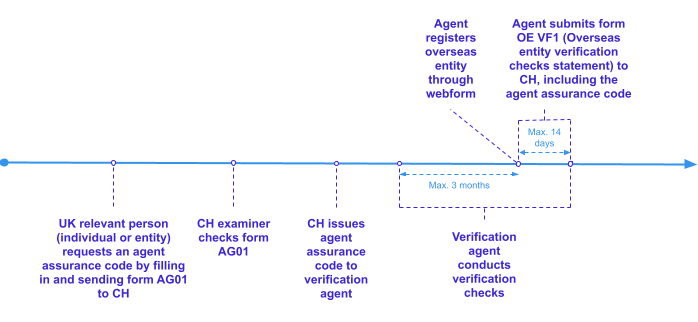

Timeline summary of the ROE verification process

The UK-regulated relevant person, either an individual or an individual acting on behalf of an entity, must obtain an agent assurance code by emailing Form AG01 to CH with details about their name, contact details, supervisory body, and AML registration number. A CH examiner checks the form, presumably manually, as it is a PDF form. If the form passes the checks, CH issues the agent with an assurance code, authorising the agent to file verification checks statements for overseas entities. Once an assurance code is issued, it is valid for all relevant persons within an entity if it was requested by an entity (i.e. employees who carry out this work) and for multiple verification checks. It is unclear how long the code is valid for.

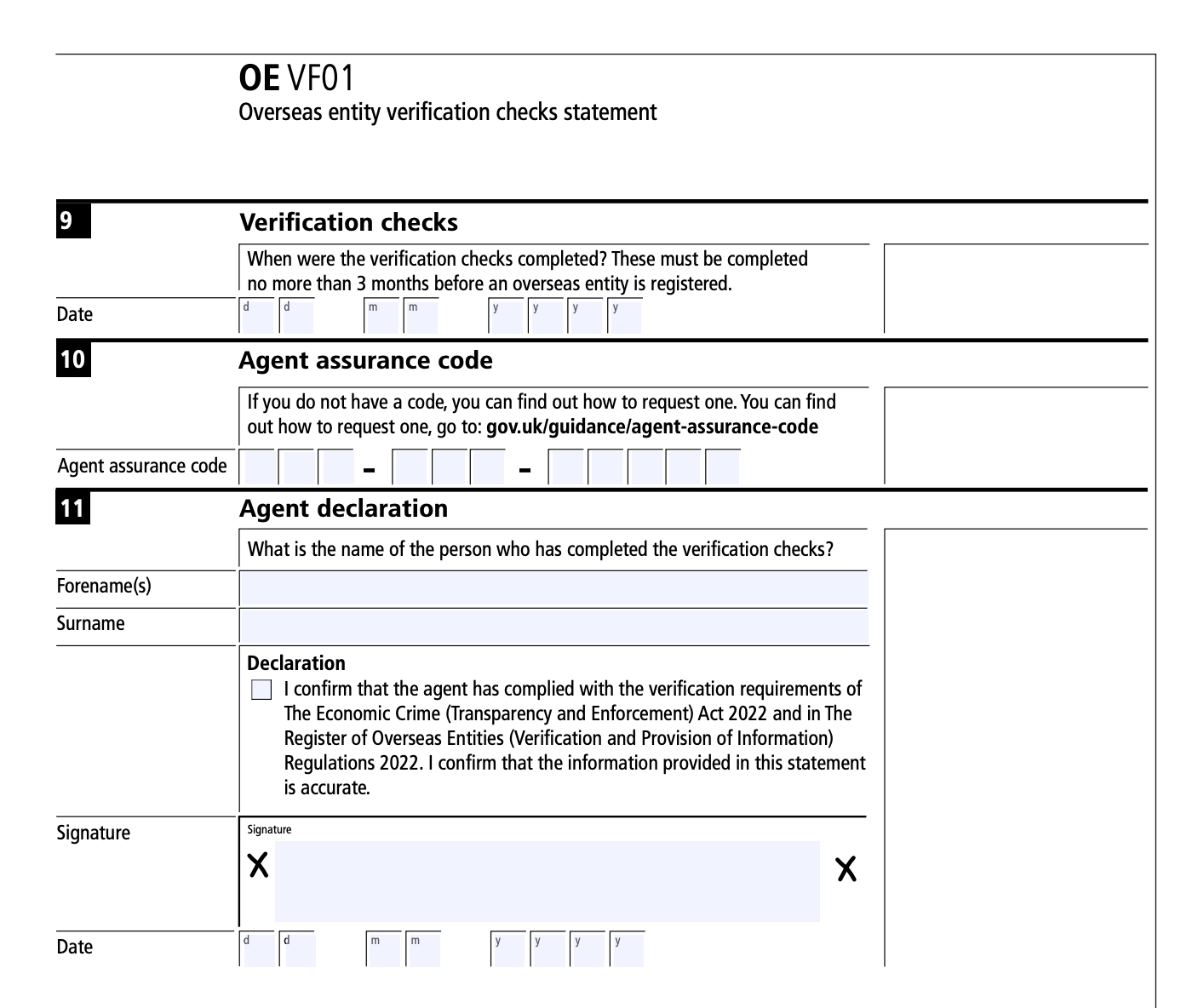

The agent assurance code is used in the overseas entity verification checks statement (form OE VF01). This is also a PDF form that needs to be emailed to CH. The verification checks statement requires information about the agent, their agent assurance code, the names of beneficial owners and managing officers verified, when the checks were conducted – but not what checks were conducted – and a confirmation statement from the agent.

The final page of Form OE VF01

It is unclear which, if any, checks CH conducts on the OE VF01 forms they receive, or how extensive these checks may be. Examples of minimum checks that CH could carry out at this stage, and presumably to some extent already does, include:

- ensuring that the assurance code is valid;

- verifying that the agent listed does indeed work for the entity, in the event that it is an entity to which the assurance code was issued;

- comparing the names of beneficial owners to the names submitted as part of the registration of the overseas entity, which should also avoid a situation in which a beneficial owner is verifying themselves, which is prohibited.

As the statement is a PDF form which is submitted by email, OO assumes that CH checks carried out at this stage are done manually.

The verification checks statement should be submitted within 14 days of registration, and should be completed no more than 3 months before the overseas entity is registered.

How are verification checks carried out?

CH has published technical guidance on registration and verification. This contains an explanation of the definition of a registrable beneficial owner through some examples and references to the legislation, information on exemptions, sanctions, protection regime and public access. It also contains a section on Verification (section 13).

The statutory instrument defines verification through the following terms:

- “Verify” means verify on the basis of documents or information in either case obtained from a reliable source which is independent of the person whose identity is being verified, and “verified” and “verification” are to be interpreted accordingly;

- Documents issued or made available by an official body are to be regarded as being independent of a person even if they are provided or made available to the relevant person by or on behalf of that person.

The guidance complements this, stating that: “Verification involves verifying information about overseas entities, beneficial owners and managing officers. Verification checks for individuals should involve looking at both evidence to match their identity as well as evidence of the condition met to be a beneficial owner (or managing officer).” This closely matches the language in the revised FATF Recommendation 24 about jurisdictions needing to verify “identity” and “status” – i.e. how someone meets the condition to be a beneficial owner. However, CH guidance focuses on only one aspect of verification, that is, cross-checking with other information sources and supporting documentation. This approach can be very effective at verifying identity, but is less effective at verifying status.

Companies House guidance on registering an overseas entity

The guidance makes it clear that the onus is on the overseas entity to identify their beneficial owners and “to provide the documents and information, or to direct relevant persons as to reliable, independent sources” (p31). For example, relevant persons are not required to verify the number of beneficial owners an overseas entity has. The guidance states that: “When a relevant person is performing verification checks we expect them to be sceptical, but not forensic. Of course, relevant persons are free to go beyond the suggestions in this guidance if they so wish” (p40). It is not clear what is meant by “forensic” here, as CH does expect agents to query information they may suspect to be forged or incorrect.

The guidance covers sanctions on the agents and beneficial owners. It is an offence for a person to submit false or misleading information without reasonable excuse, providing an exception for honest mistakes. It is an aggravated offence to submit false or misleading information knowingly. This is broadly in line with the recommendations in OO’s sanctions and enforcement briefing from April 2022. Relevant persons are also required to keep copies of any material provided by or on behalf of an overseas entity for the purpose of verifying relevant information for at least five years. They should also “document any additional steps taken to obtain further documents or information, or to verify documents or information provided to them” (p32).

While relevant persons are required to keep these documents, they are not required to either state which documents they hold or have used to verify aspects of information, nor to provide the documents to CH. It is unclear who can request this information but presumably law enforcement could do so under the MLRs.

Finally, the guidance sets out a “hierarchy of documents” (p36), clarifying what is acceptable and what types of documents are deemed more reliable and independent. It also helpfully includes a “Table of examples of documents and information in either case obtained from a reliable source which is independent of the person whose identity is being verified” (Annex A, p45). While this is undoubtedly useful, it also raises some questions. For example, “Extract from (public) company beneficial ownership register” is included as an example of an independent document to verify “Condition met to be a registrable beneficial owner (RBO) and statement as to why.” However, there are no requirements placed on this information being verified as part of that disclosure regime.

Documents to evidence “Significant influence or control” appear to be mostly “bank mandates, or other banking records”. It is unclear how an informal nominee arrangement would be verified, or how the examiner would verify that the declared beneficial owner is not a nominee.

Potential steps forward

In its approach, CH has created domestic liability, but falls short of implementing a comprehensive verification mechanism. Agents only have to declare what date they verified the information provided, and for whom, without submitting supporting evidence, such as a copy of these documents. At the very minimum, CH could require agents to explain how they verified the information and obtained sufficient assurance to consider the information “verified”, and to include information on which documents were used to do so.

As a result, CH cannot ensure the verification has been conducted satisfactorily, beyond relying on the word of the relevant person and the dissuading power of the sanctions. CH should consider collecting detail on how the information was verified, if for no other reason than as a mechanism to understand how the market is responding to and doing the work, thereby introducing a helpful policy making feedback loop. It’s also unclear how sanctions can be meaningfully enforced without additional checks on the verification checks statement.

Collecting supporting evidence would help law enforcement authorities conduct proactive investigations without risking tipping off those under investigation, by having to request the documents from the agents. Collecting information on which documents were used for the verification process and are held by the relevant persons would potentially save law enforcement agents time, as they would not have to resort to requesting documents without knowing what documents are held by the agents. To further improve this, information – including for agent assurance code requests – could be collected using online forms, which also enables the automation of verification checks.

As outlined in OO’s verification policy briefing, verification is the combination of checks and processes that a particular disclosure regime opts for to ensure that the beneficial ownership data is of high quality, meaning it is accurate and complete at a given point in time. The approach used in ROE reduces verification to cross-checking documents, which is an effective checking process that could be deployed as part of a broader set of mechanisms. These checks will be effective at verifying identity, but not what FATF terms as someone’s “status” as a beneficial owner in all instances. It is sensible to rely on third parties to source and check the information, but the responsibility for verification should not be fully delegated to these parties. CH could take follow up action, both by checking the verification statements and by doing the “forensic” part of verification, which may be an effective complement to verify an individual’s status as beneficial owner. This could for example be done by implementing a system that raises red flags based on risk or checking samples. However, CH currently does not collect sufficient information to do this effectively. In addition, there currently appear to be no checks to verify whether all beneficial owners have been declared. As such, ROE’s verification mechanism may fall short of the updated FATF guidance to the revised Recommendation 24, due to be published in October 2022. It also seems unlikely that all types of BO relationships would be verifiable using independent documents alone.

Conclusion

In summary, the ROE verification approach creates domestic liability within the disclosure process for persons within the UK jurisdiction, performing registration and verification, and includes an important verification procedure by checking against independent documents. This is a sensible approach, considering the challenges associated with verifying foreign entities, and the very short timeline CH has had to implement this new disclosure regime. However, this falls short of being part of a comprehensive verification system. CH should consider collecting additional information from verification agents on what steps were taken to satisfy the verification requirements and which documents were used to do so, including potentially the documents themselves. This is information that these agents should already have collected over the course of verification and should not constitute an extra burden to them. This would also enable CH to carry out additional checks, which CH could conduct to strengthen its verification of the status of individuals as beneficial owners, including the more “forensic” checks after the submission of information. This would also make the sanctions more enforceable. OO expects that CH will welcome and be responsive to feedback on technical implementation, as it has always done in the past.

Header image credit: Companies House

Related articles and publications

Publication type

Blog post

Country focus

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

Sections

Implementation

Open Ownership Principles

Verification