Transforming procurement systems, one prototype at a time

Since October, Open Ownership (OO) has been working on a project funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) called Transforming Procurement Systems (TPS). The project is focused on developing mitigation strategies for corruption risks during the emergency procurement processes linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as building resilience for recovery. OO’s role has been to understand and solidify the place of beneficial ownership (BO) data in these emergency processes and the recovery processes. OO has been working with Indonesia, Mexico, and South Africa to support their efforts to collect BO data and link it with procurement.

On the tech side, OO has been helped by the Global Digital Marketplace Programme (GDMP), part of the UK Government Digital Service. GDMP commissioned mySociety and Spend Network to research and build prototypes that demonstrated what could be possible when BO data is connected to procurement data. Specifically, their prototypes worked with BO data in the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS) format and procurement data in the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) format. For this project, OO has built on Bluetail, a prototype system that uses BO, procurement, and politically exposed person (PEP) data to automatically flag corruption risks in tenders. The aim for this project is to understand the benefits of using these prototypes in our target countries, whilst making the case for the standardisation of BO data.

This blog will provide a quick overview of our work so far, as we prepare to step up a gear in the new year with our hiring of a local consultant, before the deadline of the project in March 2021.

Bluetail

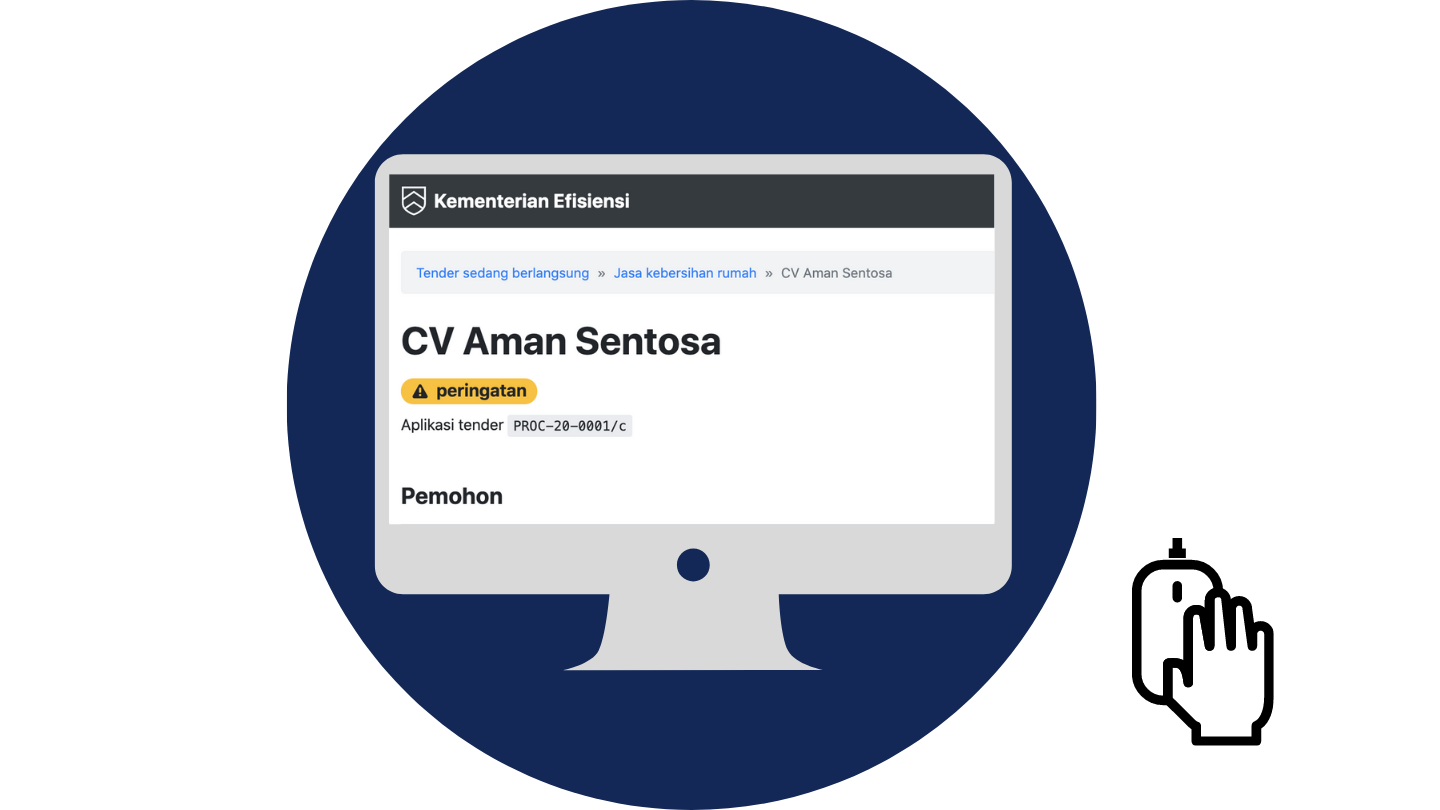

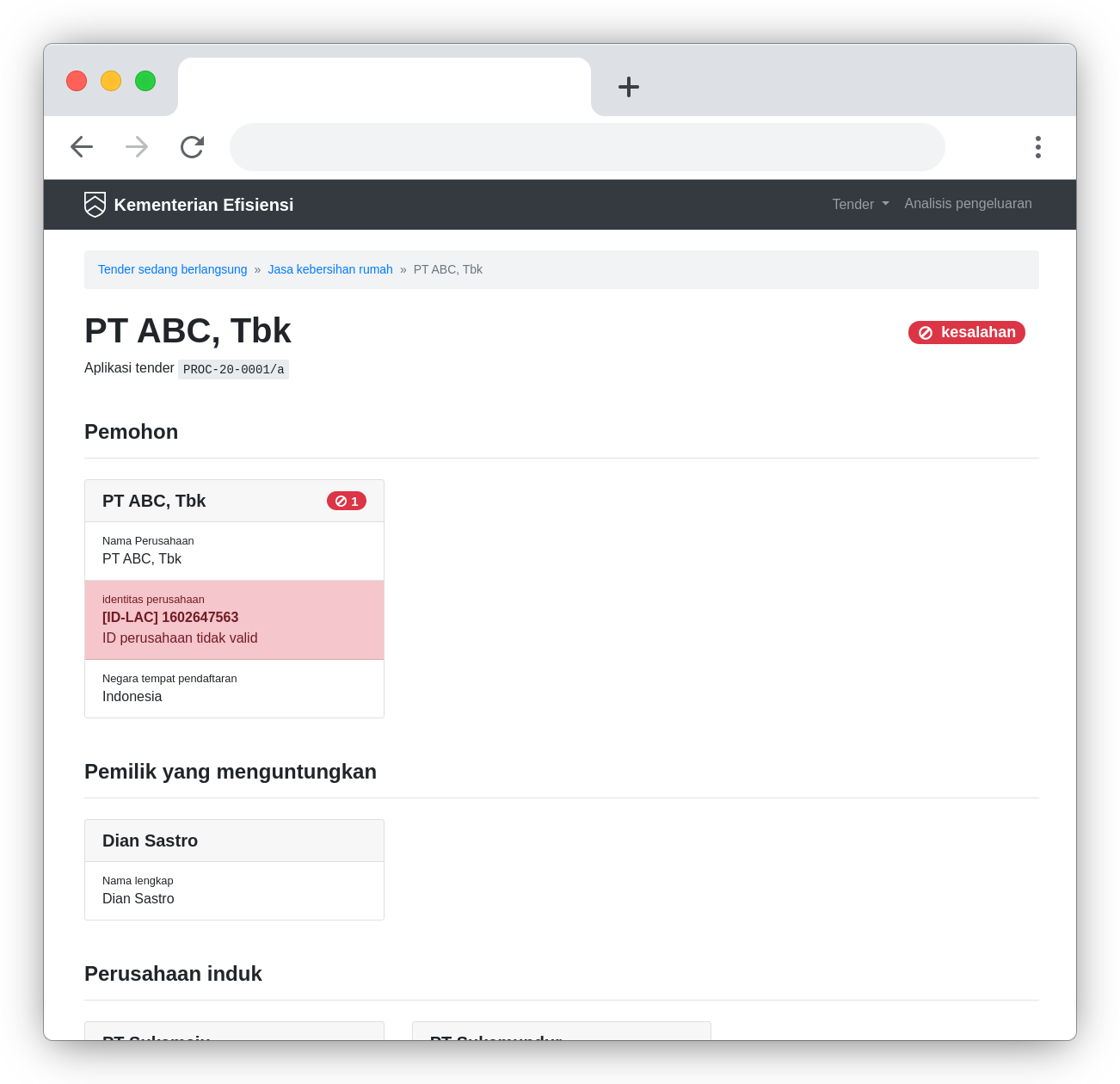

Bluetail is open source and freely available under an MIT licence. OO worked closely with mySociety and Spend Network to support Blutetail’s development, so it was natural for us to build on it for the TPS project as well. In Bluetail we saw an opportunity to make the case for open BO data. It is a clear example of where BO can help mitigate corruption risks in procurement. Importantly for our country engagements, it is also designed with government users in mind – giving them tools to screen tenders before awarding contracts.

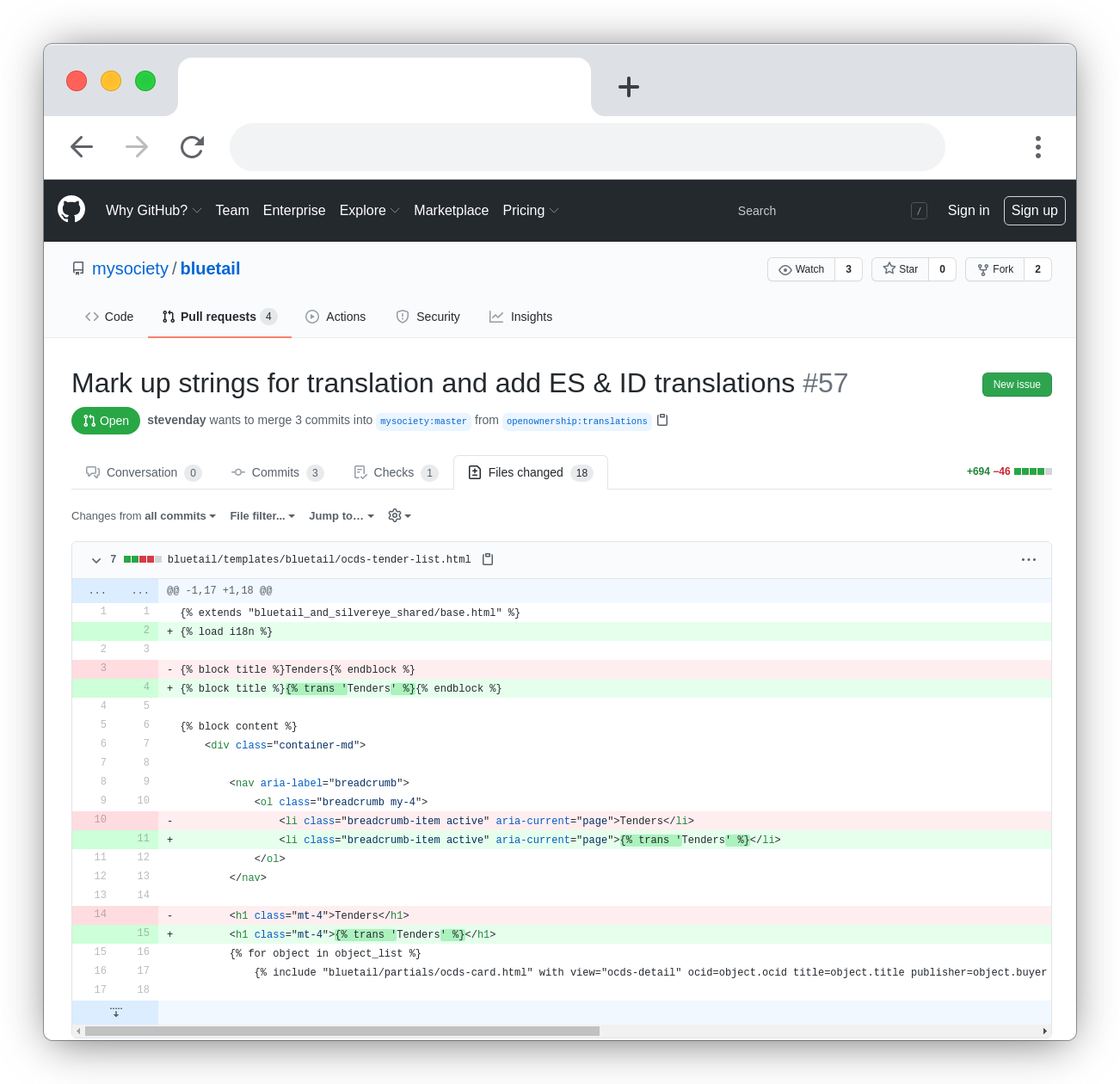

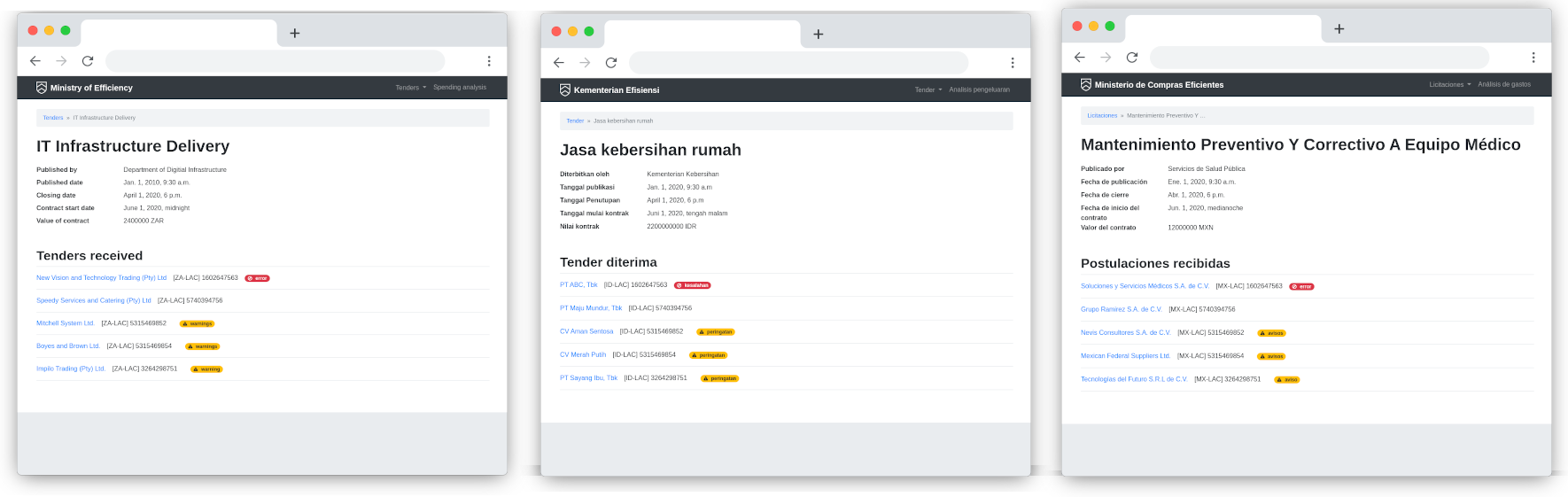

To enhance the value of Bluetail as a sales pitch for BO data, the first thing we wanted to do was translate the user interface into the languages of our partner countries: Bahasa Indonesian and Spanish. To do this, we first needed to make some changes to the code so that it was possible, then undertake the work of translating everything. Since Bluetail is open source, we could easily get our own copy of the code and make these changes. Even better than that, we are able share our improvements back with the wider community, so that everyone benefits from our work:

Here we had some great help from the GDMP team in Indonesia, as our Bahasa is sadly not as good as our Spanish or English just yet. We shared the translations on an open platform, Transifex, so that they can be reused by others.

Next, we wanted to make the example data that Bluetail includes more relatable to our partners, too. None of the countries we are working with have open BODS and OCDS data available (yet), which is why Bluetail comes with some samples to demonstrate its capabilities. These samples make sense to a British audience, because they use limited companies and offshore vehicles in Jersey. However, they are harder to understand from an Indonesia or Mexican perspective where company registration types are different and offshore companies might more commonly be in Malaysia or the US.

To make the data more relatable, changes to the code were needed. We added the capability to have separate sets of example data for each language (or even national variations of languages). We also made the data loading routines aware of the language the prototype was running in, so that they would load the correct data automatically. We have used this feature for our South African instance too, to load different data compared to the British English version, despite the fact that both use the English language.

As well as the technical capabilities, we needed new versions of the data itself. Showing off all the capabilities of Bluetail takes quite a bit of complicated BODS and OCDS data – replicating the complication of real world cartels and suspicious bidding practices that might be seen in tender processes. To make this easier for translators, we built some new features into Bluetail. We created a spreadsheet form of the data, so that they could translate the companies and people in a familiar interface, then added technical tools to take this spreadsheet and translate the BODS and OCDS JSON data.

This gave us three versions of the prototype with tenders, bidders, and corruption flags that make sense in each of the three jurisdictions with which we are working:

We are also hosting each of these versions as a fully working prototype:

- Indonesia 🇮🇩

- Mexico 🇲🇽

- South Africa 🇿🇦

The fact that we were able to produce these three translated, localised prototypes in just a few days shows the power of working in the open and sharing code as open source. Starting this prototype effort ourselves would have been out of our scope for this project, but because it was shared openly, we were able to benefit from the previous efforts. Our reciprocal work means that any future users will also be able to benefit from translations and better example data. Whilst working on our features, we even found and fixed a small bug, helping make things better for all users, even if they are only using the English version.

Data translation via BODS

The second piece of prototyping work we have been doing follows on from a recommendation mySociety made in their research report alongside the Bluetail prototype. They suggested that an API that translated internal data formats to the BODS could be a useful tool in harmonising BO data across government departments. A system that provided a common data format, they theorised, could reduce technical barriers to inter-departmental data. OO would also like to explore this avenue, and data conversion to the BODS has other benefits when trying to review and assess the capabilities of government systems. By converting data to the BODS, we force ourselves to question and understand the nuances of what it can (and cannot) represent. This hands-on process of data use is essential to making a fair judgement of data quality.

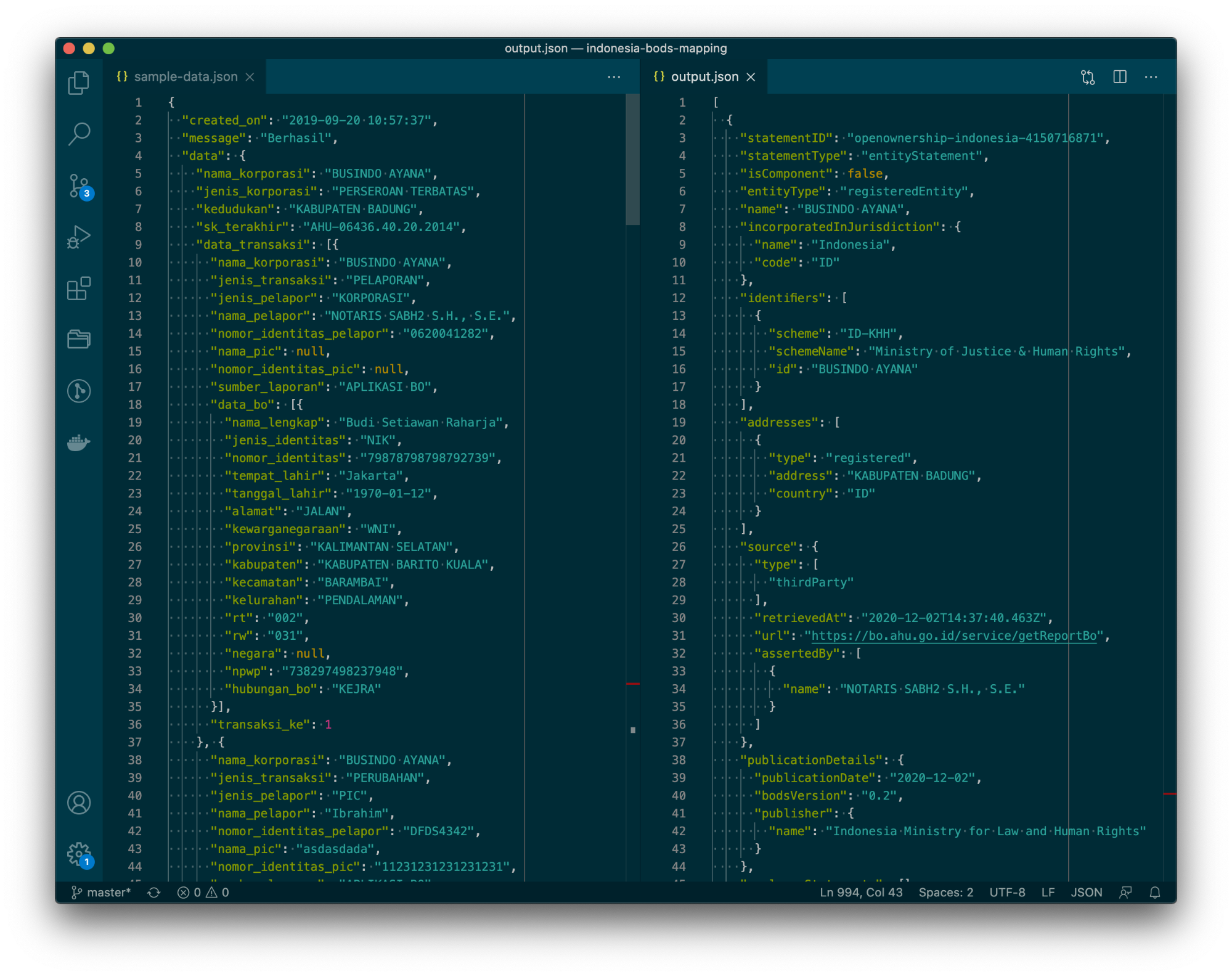

To trial this process, we have produced a prototype of a simple command-line tool which takes JSON data from Indonesia’s BO API as input, then returns functionally equivalent BODS JSON as output.

The code behind this is available on GitHub and we have released it as open source under the MIT licence. It is relatively simple Javascript code, which we hope makes it understandable to the widest audience. The code is not intended to be a production-ready system that Indonesia could use as is, but it has other benefits besides the knowledge we gained from writing it. Firstly, it lets us codify many of the modelling decisions that are necessary when publishing any data as BODS. Working from documentation and example data from Indonesia’s API, we are bound to have made mistakes of understanding. The types of modelling decisions we have made can be hard to communicate across a language barrier, whereas code is more precise and easier to reference when asking questions. For example: which name field should we attribute when a declaration is submitted by a notary? Or, how do we tell the difference between ownership changing hands and owners changing names?

Mapping data to the BODS in this way also makes it easier for us to communicate wider points of critique about systems and the legislation that backs them. BODS terminology is directly referenceable to the Open Ownership Principles, so when we talk about the importance of historical data, or unambiguous identifiers, we can point to the specific parts of the BODS schema that enable that. With local data mapped to the BODS we can highlight shortcomings with great specificity.

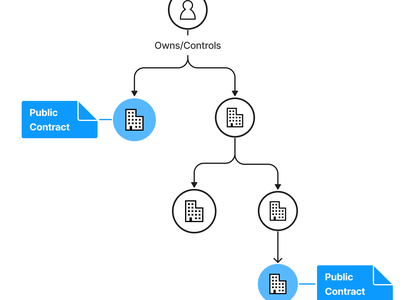

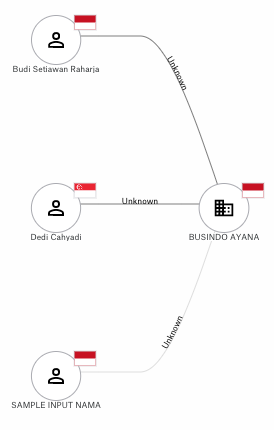

Finally, having data in BODS unlocks the potential to use other tools that work with BODS data; for example, we can present this visualisation of the example data Indonesia provided, which was generated automatically by our BODS visualisation tool from the data we mapped:

Next steps

Our next steps with these prototypes are to share them more widely with stakeholders in Indonesia, Mexico, and South Africa. We have already shown screenshots and talked about our work at high-level events, but we need to get them into the hands of the people responsible for the technical details, so that they can challenge our understanding and help us work out what might be possible in the future. We hope our forthcoming appointment of local consultants and our continued collaboration with the GDMP and wider GDS teams will help make this possible.

Related articles and publications

Publication type

Blog post

Country focus

Indonesia,

Mexico,

Republic of South Africa

Topics

Procurement,

Beneficial Ownership Data Standard

Sections

Implementation,

Technology

Open Ownership Principles

Structured data