Guide to implementing beneficial ownership transparency

Publishing beneficial ownership information

This section examines how countries can publish BO data in accordance with local privacy and data protection legislation or, in its absence, international standards on data and privacy.

Best practices for data publication

The Data section looked at how BODS can help with structuring BO data effectively, in a way that is machine- and human-readable, as well as interoperable with data from other jurisdictions.

International implementation experiences have shown that what constitutes public access to a register may vary and differ from how it is defined in the OO Principle of public access. For example, in one jurisdiction all data could be made freely available without registration, whilst in another it might only be available for a fee levied per individual record access. Though both would technically count as public, the accessibility would be significantly different. The usage and impact of BO data is likely to be highest where it is made available in open data format, i.e. where it is made freely available online as structured data without restrictive licensing. It should be searchable by both beneficial owner and company name, downloadable in bulk, and reusable by the public. This should be without the need for a fee, proprietary software, or registration. Some governments also choose to make BO data available through additional methods. For instance, via an application programming interface (API), which allows direct access to machine-readable data which can then be used as an input for other tools and products. [17] All these measures increase the number of people using the data, increasing its impact and facilitating independent scrutiny. The potential benefits of doing so are outlined in the OO policy briefing Making central beneficial ownership registers public.

Finally, it is important to highlight that historical BO data should also be kept and made available to the public. As outlined in the OO Principle of data being up to date and auditable, keeping historical data prevents an entity from obscuring its identity by changing its name or beneficial owners hiding by reincorporating. and allows for investigations in complex legal cases. Historical and auditable records are critical for law enforcement to verify ownership claims against historical records. Historical changes can be referred to during investigation even where the accuracy of data is in question, and can provide evidence of “who knew what when” to assess, for instance, whether due diligence was undertaken effectively at a particular point in time. With the exception of redactions under a protection regime, BO data should be kept and published for at least the lifetime of a company, and ideally after its dissolution.

Mitigating potential negative effects of public access

BO data has been published in dozens of jurisdictions. Opponents of public registers argue that publishing data presents serious security risks to certain individuals. For instance, some stakeholders in Germany have voiced concerns over identity fraud and kidnapping. Research has shown that whilst company directors are disproportionately at risk of identity fraud, this risk is most serious when information about them has already been published online, such as on social media. OO research across a range of jurisdictions with open BO data registers has been unable to identify documented examples of serious harms that have arisen from their publication to date.

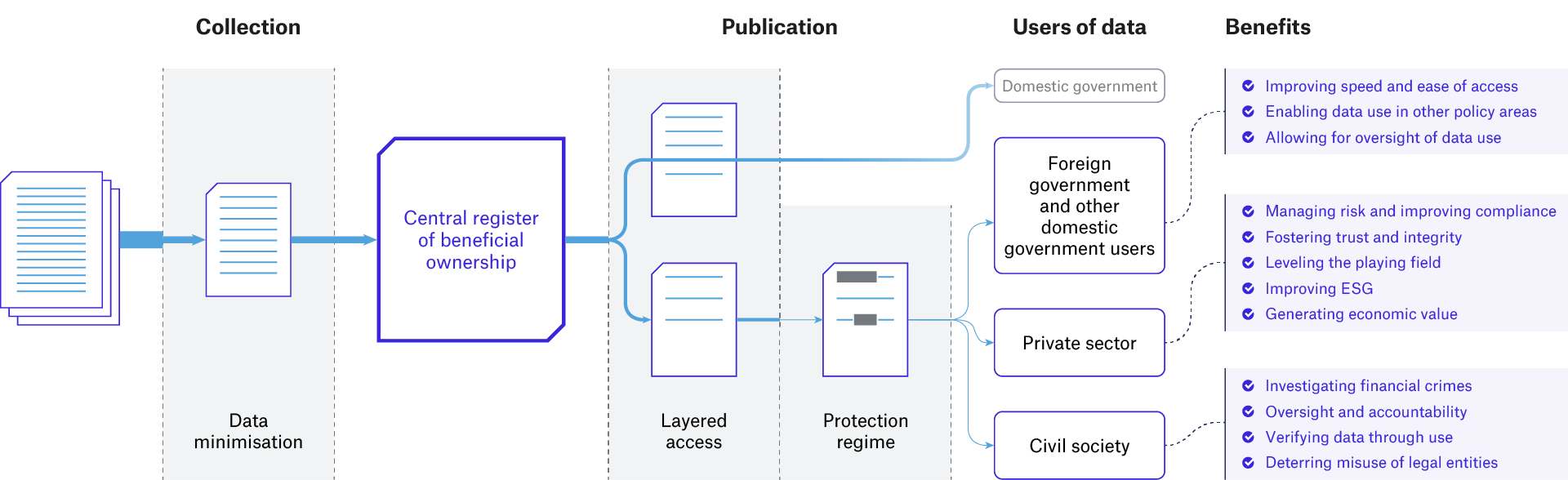

The potential benefits of making BO data need to be weighed against the potential harmful effects of reducing privacy. These will differ per jurisdiction, and each implementer will need to assess what the potential effects are through stakeholder consultations. Registers have been mostly implemented in Global North countries so far. It is likely that if BOT reforms are considered in other contexts, these will face their own set of potential harms. For instance, based on OO’s experience supporting implementation in Mexico, there are specific concerns about risks to personal safety (e.g. kidnapping) based on Mexico’s specific legal and security environment. Similar concerns have also featured in Mexico’s debates about the asset disclosures of public officials. Whatever concerns arise, implementers can take a number of steps to ensure that potential harms are mitigated (also illustrated in Figure 1):

1) Adhere to the principle of data minimisation

Implementers should follow the principle of data minimisation and only collect data that is adequate (sufficient to fulfil the stated policy aims), relevant (has a rational link to that purpose), and limited to what is necessary (not surplus to that purpose). Disclosure regimes should not collect any unnecessary data – especially not sensitive data (e.g. physical appearance or racial background), which also often needs to meet a higher legal threshold for processing. In practice, this means that governments will need to make careful decisions about what data to collect. For instance, they may decide that collecting business addresses, rather than personal addresses, is sufficient to achieve the policy goals of their register.

2) Adopt a system of layered access

One common way to navigate potential publication issues related to personal data is to implement a system of layered access in which different information is available for access by different audiences. Whilst investigative authorities will have access to beneficial owners’ full details – including personal contact information and their full date of birth [18] – the data that is made publicly available would be more limited, but sufficient to facilitate accountability and public oversight (e.g. a service address instead of a residential one). BO data disclosure forms should clearly indicate which fields of data will be accessible only to the competent authorities and will not be made public as this can help ease potential confusion and reduce privacy objections during implementation.

3) Apply a protection regime

Implementers can also mitigate potential negative effects arising from the publication of data by providing for exemptions to publication in circumstances where someone is exposed to disproportionate risks. This is a common feature of many BOT regimes and should focus on mitigating risks emerging from the publication of the data. For instance, a person might be a member of a particular religious community and be the beneficial owner of a company whose activities conflict with the principles of that religion. The protection regime should also include risks emerging from the publication of any of the personal data. For instance, someone who has been stalked and harassed has a legitimate case not to have the combination of name and residential address published. A protection regime should have an application system with the possibility to have certain or all data fields protected before these are published, when substantiated by evidence. These should be reviewed according to a set of narrowly defined conditions, to avoid creating significant loopholes in a disclosure regime.

Figure 1: Mitigating potential negative effects in a BO disclosure regime

For further discussion on the benefits of publishing BO data, and strategies for mitigating any potential negative effects, please see the OO briefings on Making central beneficial ownership registers public and Data protection and privacy in beneficial ownership disclosure. For more on how to balance public interest and privacy concerns in the case of trusts, please see the OO briefing Beneficial ownership transparency of trusts.

For case studies of the emerging impact of public registers, see the OO impact stories Early impacts of public registers of beneficial ownership: Slovakia and United Kingdom.

Footnotes

[17] In Ukraine, YouControl uses BO data from the State Enterprise Registry as a key data source for the innovative commercial due diligence tool it has developed. Sqwyre in the UK, on the other hand, combines bulk data from the UK register along with other data sources to advise firms on how location selection of their business may affect earnings.

[18] Tymon Kiepe, “Making central beneficial ownership registers public”, OO, May 2021, 17, https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/making-central-beneficial-ownership-registers-public/.