Guide to implementing beneficial ownership transparency

Data considerations for beneficial ownership registers

In this section, the following will be examined: how to scope out the information collected within declarations; how to implement mechanisms to improve data quality according to the OO Principle of verification; and the importance of standardised, well-structured data. OO has also developed a prototyping tool for a basic system for collecting BO data.

What information to collect

The implementing country’s definitions and legislation, discussed in the Legal section of this guide, will lay the basis for assessing:

- which entities will be required to make BO declarations (ideally according to the OO Principle of comprehensive coverage of persons and entity types);

- which entities and people will be disclosed in those declarations (SOEs, PLCs, legal owners, trusts, nominees, intermediate companies, etc.);

- which details of those people and entities will be collected in declaration forms; and

- what information about the nature of ownership or control between entities-and-entities and people-and-entities will be collected.

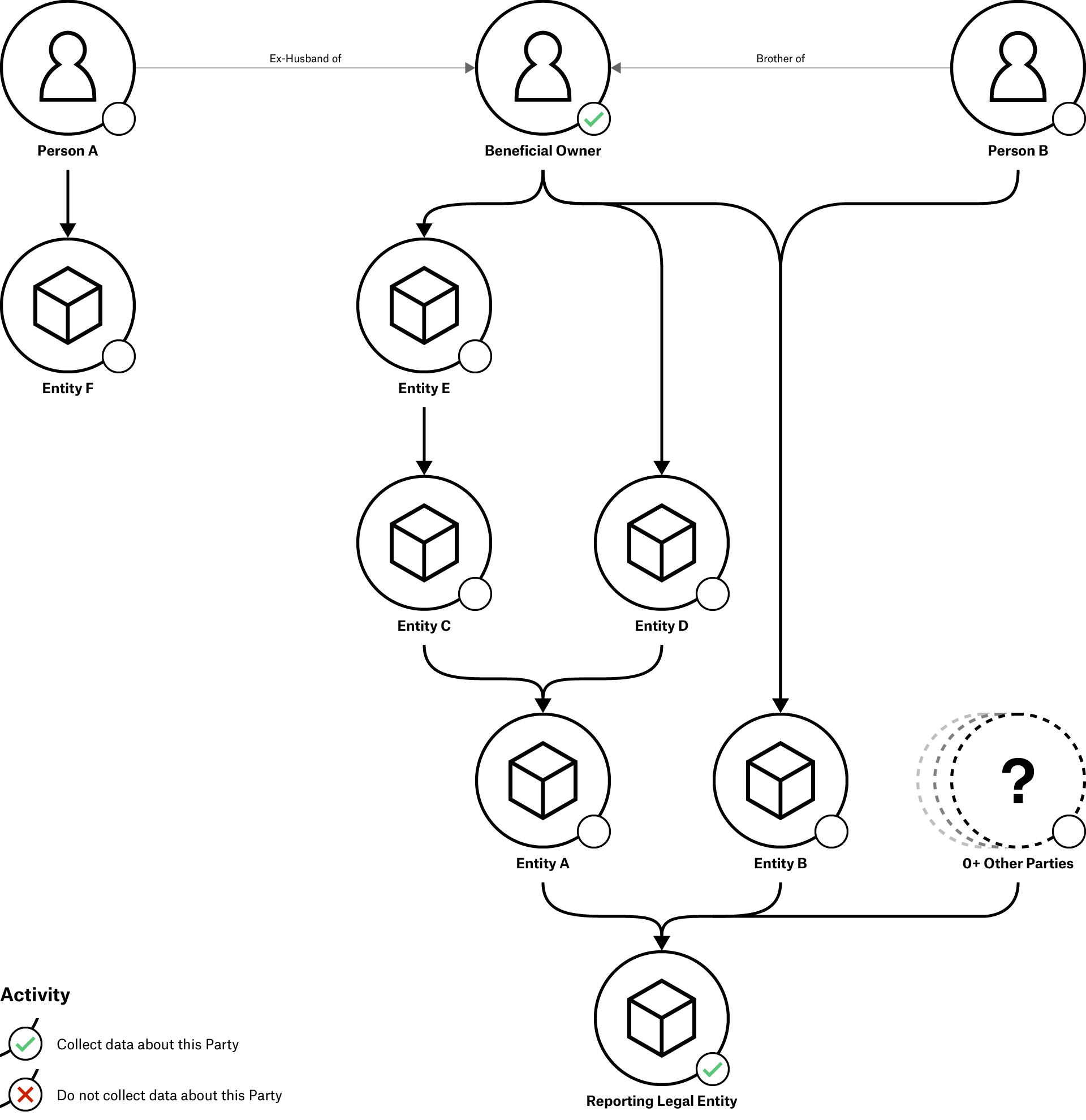

Once there is clarity on each of these points, the information disclosed should be assessed to ensure that it will meet the overall policy objectives behind creating a public BO register. By looking at real-life (or hypothetical) examples of ownership and control structures, the effects of proposed regulations can be tested. An activity sheet like the one illustrated in Figure 1 may help ensure there is a shared understanding of the declaration requirements and their implications between the various stakeholders involved in the process.

Figure 1: Example activity sheet for checking shared understanding of what is disclosed in a declaration

It is important to check that enough information is collected about how a company is owned and controlled, even where its declaration is looked at in isolation. Sufficient detail about intermediate entities (those that sit between beneficial owners and declaring companies when ownership or control is exercised indirectly) should be collected. This means that a declaring company might also feature as an intermediary in other declarations. OO recommends using company identifiers to ensure information disclosed in different companies’ declarations can be brought together to aid understanding and analysis. That way, it will be apparent when the same company appears in two different declarations, even if the names do not match (due to misspellings or the use of acronyms).

The use of good-quality company or person identifiers is key when it comes to combining beneficial ownership data with other information, e.g. procurement data. To facilitate this, our Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS) shares a common approach on identifiers with other standards including the Open Contracting Data Standard which helps publishers structure data on public contracts (see detailed guidance). The value of this common approach can be seen in the Bluetail prototype developed in 2020 to show what is possible when beneficial ownership data is connected to procurement data to automatically flag corruption risks in tenders (see BO data in procurement briefing).

When considering how beneficial ownership data will be used with other types of information, the needs of data users should be checked against the proposed information flow (see the Systems section). Any implications for data collection need to be flagged early in the implementation process.

The OO beneficial ownership disclosure workbook illustrates a series of fictional company ownership structures, and is designed to help implementers explore the extent of information to be disclosed in different ownership declarations.

Structuring and standardising data

In Ukraine, early publications of BO data contained all the information relating to the beneficial owner and their relationship with a company in a single text field in the company register (unstructured data, as shown first in Table 1). Whilst this enabled the public to access the data, the usability and quality – and therefore impact – of BO data can be significantly greater where data is standardised and structured. Separating out information into different fields, as below, makes it easier to verify and analyse.

| Unstructured | Structured | |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of ownership or control | Nature of ownership or control | |

| This beneficial owner indirectly herself, or through her children, owns 27% of the declaring legal entity’s shares through the following shareholders of the legal entity (1) “Angerujjheit B.V.”, registration number in the Netherlands 64739564, registered office: Byterslaan 105, NL-4722GF Amsterdam, Netherlands; (2) “RigaTech Systems Ltd.”, registration number in the United Kingdom: 396654, registered office: P.O. Box 124, Company Services Ltd. Main Road, London, United Kingdom. | % Aggregate share ownership | 27 |

| % Aggregate control via voting shares | 27 | |

| Direct share ownership in declaring entity | 0 | |

| Direct voting control over declaring entity | 0 | |

| 1.1 Intermediate legal owner(s) | ||

| Legal owner 1 | ||

| Name | Angerujjheit B.V. | |

| Registration authority | Commercial register of the Netherlands | |

| Registration number | 64739564 | |

| Legal owner 2 | ||

| Name | RigaTech Systems Ltd. | |

| Registration authority | Companies House, UK | |

| Registration number | 396654 |

There are multiple advantages to standardising the way that BO data is collected, stored, and published. In particular, structured data allows for automated verification checks on data. For instance, making sure it is in the right format or cross-referencing it with other government databases.

Structuring BO information in a standard format makes it easier to link with other jurisdictions’ data to better understand international ownership structures. This can reduce the need for, and resources dedicated to, formal and lengthy mutual legal assistance requests between different jurisdictions’ authorities.

If you are considering creating a system that holds beneficial ownership information, especially one that will publish data in line with BODS, please consult our technical guidance on considerations for relational database design. This is designed for use by technical professionals, especially those with a role in the database design and technology architecture of company registers and/or sector registers.

OO has developed a prototype global BO register that shows how linking data between sources could work. The register enables declarations from several different countries to be joined to create international ownership diagrams, such as this one.

For both the standardisation and structuring of BO data, BODS is a useful reference point and resource. BODS describes what data should be collected and the format it should be published in. The data schema describes how data about the beneficial owners of a legal entity can be organised. Reviewing this data schema can be a useful input to decisions that are made at the early, legislative stage of implementing BOT reforms.

Developers may wish to consult OO’s guide to the data model, schema, and system requirements for using BODS. To create BODS data, this template can be followed. The data review tool can be used to check that BODS data is valid, or to convert data in the BODS template into BODS JSON format. BODS data can be easily transformed into visual representations of corporate structures through OO’s visualisation tool. OO’s technical team can provide assistance on how to implement BODS in any jurisdiction.

Collecting beneficial ownership information and creating data

Once a jurisdiction has decided what information will be collected, it will need to consider how companies will submit their declarations. At this stage, the focus should be on making the declaration system clear and user friendly.

Well-designed forms make it as easy as possible for users to provide accurate and unambiguous information. This reduces the number of accidental errors and lowers the compliance burden on reporting entities. Submitting more accurate information becomes easier, and disguising the submission of deliberately false information as mistakes becomes harder.

Broadly, once a declaration form is created, “yes” should be the answer to the following questions:

- Is it clear which people and companies will fall into the scope of the disclosure process?

- Is the form easy to understand and navigate?

- Is it easy for people to supply good quality data for each field?

- Is it easy for companies with very simple BO structures to make their declarations?

- Can the full range of BO structures, declarable by law, be disclosed via the form(s)?

- Can form submissions be linked to data in other official databases, so that companies do not have to submit the same information multiple times?

Testing the form with a representative sample of companies will help to re-draft and improve it. Involving state agencies which are potential users of BO information when reviewing tests of the form is also recommended.

Beneficial ownership declaration forms: A guide for regulators and designers presents in-depth advice on form development, plus an example BO form. Relational database design considerations for beneficial ownership information provides technical guidance on considerations for relational database design when building a system that holds beneficial ownership information.

Verification of beneficial ownership data

Another consideration around BO data is how to verify the information submitted. Verification is the combination of checks and processes to ensure that BO data is of high quality, meaning it is accurate and complete at a given point in time. To maximise the impact of BO registers, users and authorities must be able to trust the data contained in a register. Verification systems help increase confidence that the representation of ownership in a register has a high degree of fidelity to the true and current reality of who owns or controls a particular company.

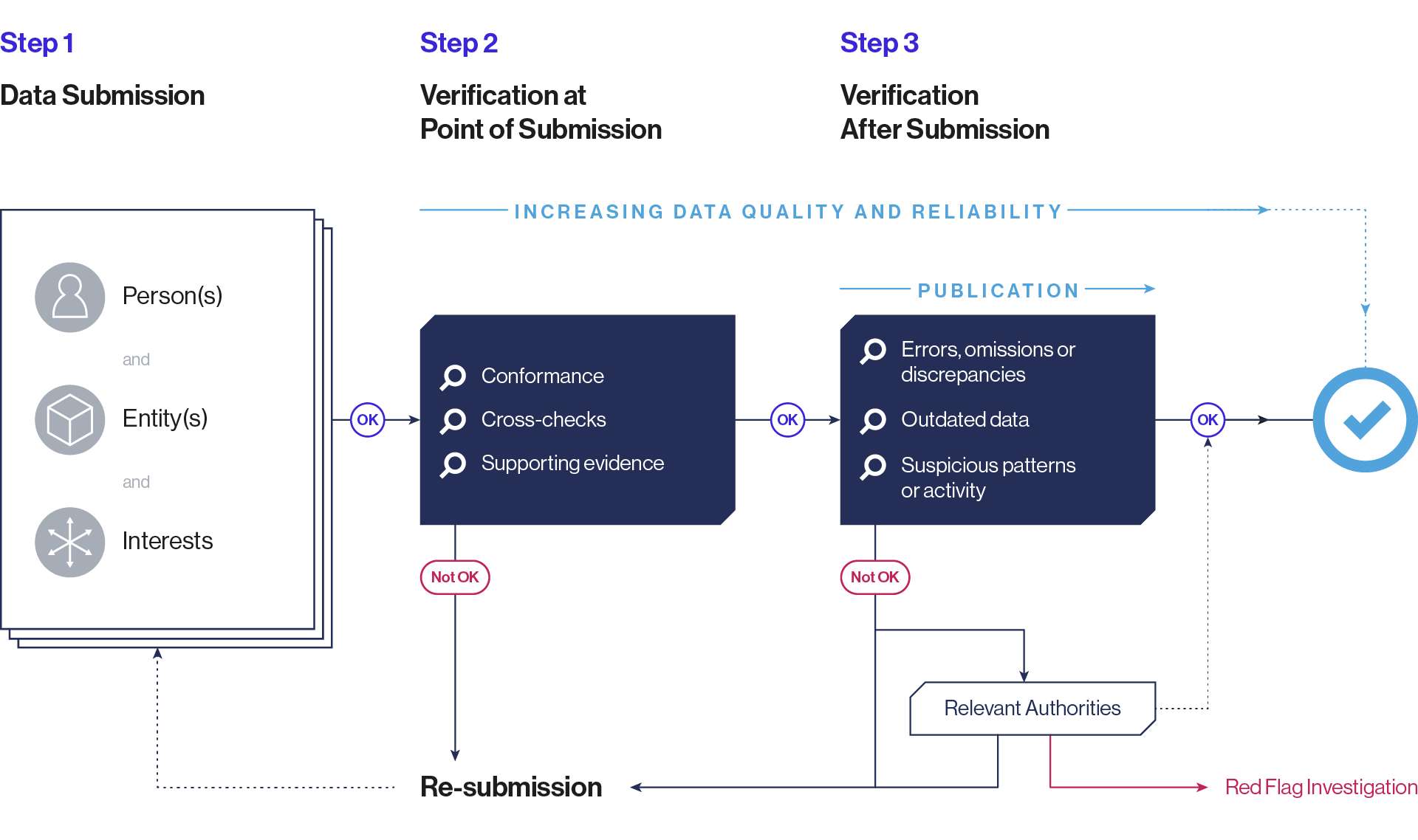

Figure 2: Designing verification systems

Data verification can take place at the point BO data is submitted and after its publication, and may range from the relatively straightforward (e.g. whether a birthdate field contains a date in a valid format) to the more technically complex (e.g. cross-checking information with other government systems). [15] BO verification systems should, as a minimum, cross check the details of domestically registered firms, such as the company number, with the other government registries. For non-national BOs, it may be more challenging to verify information (e.g. verifying a passport scan as supporting evidence) due to the legal and technical challenges associated with automatic data sharing between countries and the lack of digitally available information in some registers. Similar challenges may arise for foreign companies (e.g. for procurement-focused disclosure regimes). Whilst not always easy to verify, foreign company numbers should still be collected and published as they enable a wide range of users, from law enforcement to civil society, to conduct their own additional checks when they suspect wrongdoing.

Additionally, verification by the public is made possible when BO information is published as open data (see Publish section). Wide public scrutiny drives up the likelihood of identifying inconsistencies or potential wrongdoing and can complement government verification checks. Harnessing this as an effective verification measure would require jurisdictions to create a feedback or reporting mechanism to allow private sector actors, the public, and civil society organisations (CSOs) to report inaccuracies in data published in the BO software. Such a mechanism exists within the UK’s register, for example, and enabled over 77,000 suspected discrepancies in BO data to be brought to official attention during 2018 and 2019. [16] Adopting a risk-based approach to investigating the discrepancies reported (for example, by prioritising firms in sectors associated with high corruption risks or those that have been the subject of multiple user error reports) would help limit the amount of resources required for subsequent investigations. OO sees this as a complementary verification measure. Disclosure regimes should not rely on verification through publication alone.

OO’s policy briefing on the verification of BO data explains the overarching principles that underpin effective systems and procedures that help increase confidence over the accuracy of BO declarations.

Footnotes

[15] The precise nature of checks and the point in the process at which they occur will need to be incorporated into the information flow diagrams, outlined in the Systems section.

[16] The effect of this on data quality within the UK register can only be inferred, as public information on the investigations and actions resulting from the reporting of suspected discrepancies is limited. See: “Annual Report and Accounts 2018/19”, Companies House, 18 July 2019, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/822078/Companies_House_Annual_Report_2019__web_.pdf.