Use and impact of public beneficial ownership registers: Denmark

Denmark’s comprehensive approach to beneficial ownership transparency

Ensuring compliance through clear guidance and dissuasive sanctions

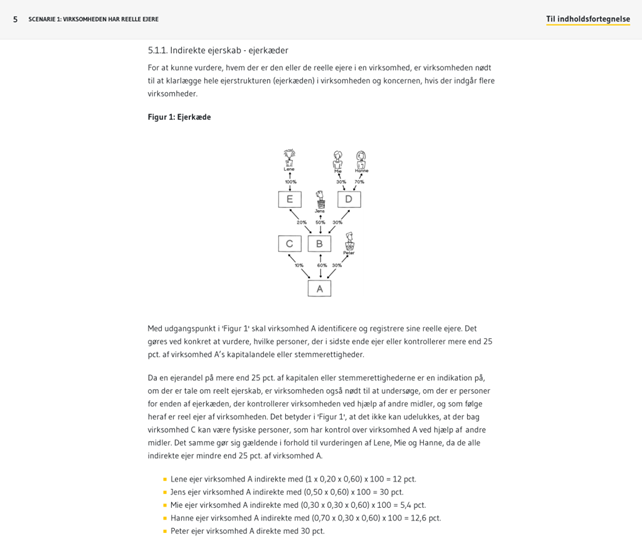

In 2019, 96% of all corporate vehicles covered by the BO regime had disclosed their BOI to the CVR.[21] Providing clear guidance on the disclosure requirements and obligations can be a relatively simple but effective way of enabling compliance.[22] The DBA has developed comprehensive guidance to support users in understanding which corporate vehicle types are required to disclose BOI, how a beneficial owner is defined in the law, and how to establish whether any individuals meet this definition using different scenarios (Figure 1).[23] The guidance also includes what to do when the company cannot identify its beneficial owners, as well as where to look for information about companies in foreign jurisdictions if, for example, the declaring company is owned by an entity registered abroad.[24]

In order to continue enabling high levels of compliance, the DBA should update its guidance in line with legislative changes, such as new obligations applicable to trusts and similar legal arrangements introduced in 2021.[25] At the time of writing, the government’s most recent update to the guidance was in 2017.

Figure 1. DBA guidance showing how to determine beneficial ownership held indirectly[26]

The legislative framework also includes dissuasive sanctions to encourage companies to comply with the legal requirements to disclose adequate, accurate, and up-to-date BOI. The law includes administrative, civil, and criminal sanctions. For example, up to three years after a company is registered, the DBA can require a company to prove that the information disclosed at the time of registration is still valid.[27] Failure to provide sufficient supporting evidence can result in a fine for each day or week of noncompliance.

Failing to disclose BOI can also have a direct impact on a company’s ability to do business. For a majority of corporate vehicles, disclosing BOI is required to complete corporate registration and subsequently be assigned a CVR number, and failing to comply with this obligation is considered a criminal offence. Moreover, company auditors are required to report BOI in annual reports, which are important reference documents used by investors and other private sector stakeholders. In some cases, failure to disclose BOI can lead to dissolution of the company. The DBA dissolved 7,500 companies in the first year after launching new requirements on BO disclosure.[28]

Including legal entities and arrangements in a single register

In Denmark, the DBA is responsible for centralising BOI on all corporate vehicles covered by the Danish legal framework.[29] This means both legal entities and arrangements are centralised in one register. This has benefits for both the collection of and the access to BOI:

- For the government, it saves resources otherwise required for the coordination, standardisation, and de-deduplication of information spread across different registers, managed by different agencies.

- For regulated entities, it reduces the time and cost of complying with AML obligations, as compliance officers can access information in one place.

- For those submitting declarations, it allows them to disclose information to authorities only once by using the same self-service portal for all new registrations and updates.[30]

- For citizens and businesses, it allows them to easily stay informed on who owns any type of corporate vehicle to support decision-making and public oversight.

Whilst publicly listed companies (PLCs), along with a number of other corporate vehicles, are exempt from disclosing their BOI on the CVR, the government has produced guidance for when a company has a PLC as part of its ownership chain.[31]

The CVR continues to incorporate new types of corporate vehicles into the register, including parish councils in June 2023.[32] Since 2021, the Danish regime also includes trusts and similar legal arrangements. Whilst common law trusts do not exist under Danish law, trusts or similar legal arrangements established under the laws of other countries are obliged to have their beneficial owners registered in the CVR. Trusts and other legal arrangements are required to disclose their beneficial ownership according to certain criteria defined in law, for example, if the trustee or person holding a similar position is a resident of Denmark, or if this person resides outside of the EU but enters into a business relationship or acquires real estate in Denmark.[33] Foreign trusts are required to provide a Danish contact address.[34] In addition to enabling compliance and data use, ensuring the reforms cover the widest range of corporate vehicles also closes potential loopholes.[35]

Digital approaches to ensuring accuracy

The DBA has implemented a number of measures to help prevent and detect possible errors in BO declarations. This combination of checks and processes is essential to the overall effectiveness of the reforms by ensuring data accuracy and improving the confidence in and reliability of the data.[36]

Using a government digital ID

The registration of companies and submission of BO declarations makes use of a government digital ID called MitID to ensure that individuals who make the declaration actually exist and are who they say they are.[37] Users can get a MitID by scanning their ID and their face, or through an in-person appointment, meaning their identities are already verified.[38] Someone’s MitID is tied to their social security number issued by the Central Register of Persons (CPR) and is used by nationals and residents to access public services online.[39] As part of a BO declaration, those submitting information need to provide the beneficial owner’s social security number. An individual’s MitID, their CPR number, and their address in the Danish Address Register (Danmarks Adresseregister, DAR) are all connected, reducing the scope for errors to be submitted. Information is automatically cross-checked against the other information in the CPR and the DAR – for example, detecting if a person is recorded as being deceased, missing, a minor, or without a registered residential address.[40] These checks are easier to carry out because the information is structured.[41] Individuals declared as beneficial owners are also notified that this has happened, in case they dispute the declaration.

Whilst this is a reliable approach to identity verification, most data users interviewed for this report pointed out its limitation for foreign and non-resident legal and beneficial owners. They explained that foreign and non-resident individuals cannot obtain a MitID number. Therefore, to verify their identities, authorities require a copy of the beneficial owner’s passport, which will be scanned and verified automatically. This helps to ensure a person exists, but is less reliable for ensuring someone is who they say they are. Non-Danish addresses are verified using an international database and by sending a physical letter to the address.[42]

Manual checks

In addition to automatic checks, the DBS also carries out various manual checks. In 2019, the DBA selected a sample of 500 disclosures to check they were accurate and up to date.[43] They also use a risk-based approach to check records that present incomplete data or raise a potential red flag; for example, where a corporate vehicle is legally owned by a company or trust registered in a tax haven.[44]

Up-to-date and historical records

To ensure data is as up to date as possible, the Danish regulations also require corporate vehicles to review whether there are any changes to their beneficial ownership on an annual basis as part of annual reporting. Any changes relating to a natural person trigger a notification to the affected person. Historical records of beneficial ownership with start and end dates are available on each entity’s record. Even if a company is dissolved, the managers of the former company are required to keep a record of BOI and documentation for five years after the individual ceases to be the beneficial owner of that company.[45] On the CVR, the names of the beneficial owners remain part of the record. However, the address and country of residence are removed five years after an individual ceases to be a beneficial owner.[46]

Widespread use

Finally, widespread use of data can improve its quality, provided feedback mechanisms are in place. The more the data is used, the more opportunities to spot and rectify any potential inconsistencies or errors.[47] As per EU standards, financial institutions and other professionals covered by AML obligations are required to report any discrepancies between BOI they collect as part of customer due diligence (CDD) and know-your-customer (KYC) checks, and information held on the CVR. Public scrutiny of the information can be complementary to more formalised verification checks. For example, as explained in more detail later, corporate data service providers that reuse and republish BO data carry out additional checks on the data as part of their service offer. The marketing manager of one of these companies explained how they ingest data from the CVR onto their platform on a daily basis and have a team of people to manually go through the data to identify potential wrong entries. However, these are not reported to the CVR, and there does not appear to be a dedicated mechanism nor guidance for reporting any errors detected apart from the legal reporting obligation for competent authorities.[48]

Open access to structured and interoperable beneficial ownership data

In order to be most useful and usable, BOI should be collected, stored, and published in a structured way.[49] Doing so also helps reduce the cost of collecting, verifying, and storing BOI.[50] By making the register publicly accessible, Denmark ensures the widest set of potential data users has access to the information.[51] As of November 2023, anyone can access and reuse information through an online portal, without registration or fees.

The structure of the data and the formats in which it is available also enable its widespread use. Every newly registered entity is required to declare its beneficial owners to be assigned a unique CVR number. A CVR number is a persistent unique identifier. It is also linked to the DAR, which contains all addresses in Denmark, including coordinates and a unique identifier.[52] Using unique identifiers helps integrate the datasets and verify the information.

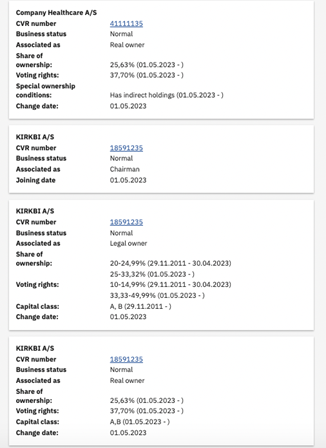

The CVR portal is searchable by individual, company, and CVR number. It allows users to view all companies in which an individual is involved, including as a beneficial owner, shareholder, and director (Figure 2). It also shows all corporate vehicles that are registered at the same address. On the portal, the CVR only provides a name, address, and details about the ownership and control relationship between an individual and a company. However, as individuals are uniquely identified through their CPR number, there is less need for secondary identifiers to see if, for example, John Smith who is a beneficial owner of Company A is the same John Smith who is a beneficial owner of Company B. This reduces the risk of identity theft. The register also provides information about legal ownership, making it possible to understand full ownership chains, at least for corporate structures based fully in Denmark.

Figure 2. The CVR portal showing all corporate vehicles in which a specific individual is involved[53]

Data users can subscribe to email notifications about updates to information on a specific company, including if a company’s ownership and control changes. This functionality, along with ease of access and searchability, has been widely reported as extremely valuable by media professionals specialised in business monitoring and financial crime investigations, as illustrated in the second section of this report.

Provision of an API

The register enables the integration of BO data into a range of other systems, software, and processes via an Elasticsearch-powered API.[54] The API and the data structure enabled Open Ownership to map the data to the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard[55] – a common structured data format which enables collecting, sharing, and using data on beneficial ownership. Data service providers have also been able to connect BO data with many other sources of public data, thereby maximising its potential to be used as part of a data ecosystem that serves a wide range of purposes. This is illustrated in case studies in the second part of this report.

The API is updated in near real time, and also allows users to download BO data in bulk, enabling additional types of analysis.[56] Many investigative journalists who regularly use BOI from the CVR mentioned that being able to search by country would be very useful. For example, looking at countries that are internationally considered as tax havens can help journalists investigating tax evasion to help spot any potentially suspicious corporate connections. These types of queries are not possible through the public portal, but are through the bulk data. The data is available in bulk through the API, or in theory by scraping the information from the portal. However, because the CVR’s data use policy prohibits the scraping of its data with potential liability under Danish law, these queries are only legally possible through the API.[57] The provision of bulk data via an API therefore allows the DBA to maintain oversight over its use.

The API is only available upon request, after the submission of certain information to the DBA. If approved, the DBA will issue a username and password to access the API. The API provides access to a larger number of data fields than the CVR portal search and allows the information to be audited and used in a greater number of ways. Therefore, it seems reasonable that the DBA should capture more information about the API’s use and users in order to provide a means of recourse in the event of misuse, and it is possible to see which users are making calls on the API when. The DBA withholds API data relating to “entities protected against unsolicited advertising”.[58] This data is only available to API users if they formally commit to respecting those same protections, but is otherwise – along with the rest of the CVR’s data – free to use and reuse for commercial and non-commercial purposes, under the terms of use of Danish public data.[59]

Endnotes

[21] FATF, Best practices on beneficial ownership for legal persons, (Paris: FATF, 2019), https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/guidance/Best-Practices-Beneficial-Ownership-Legal-Persons.pdf.

[22] Open Ownership, Principles for effective beneficial ownership disclosure (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/principles/.

[23] See: Erhvervsstyrelsen, Vejledning om Reelle ejere (Copenhagen: Erhvervsstyrelsen, 2017), https://erhvervsstyrelsen.dk/vejledning-reelle-ejere.

[24] “Udenlandske virksomhedsregistre”, CVR – Det Centrale Virksomhedsregister, n.d., https://datacvr.virk.dk/artikel/udenlandske-virksomhedsregistre.

[25] LBK nr 1062 af 19/05/2021.

[26] Erhvervsstyrelsen, Vejledning om Reelle ejere.

[27] As mentioned in Chapter 8 of the DBA’s guidance. See: Erhvervsstyrelsen, Vejledning om Reelle ejere.

[28] FATF, Best practices on beneficial ownership for legal persons.

[29] As listed under chapter 19 of DBA’s guidance. See: Erhvervsstyrelsen, Vejledning om Reelle ejere.

[30] “Søg på Virk”, Virk, n.d., https://www.virk.dk.

[31] Paragraph 5.1.1.2 of the DBA’s guidance. See: Erhvervsstyrelsen, Vejledning om Reelle ejere.

[32] Erhvervsstyrelsen, “Overførsel af oplysninger om menighedsrådenes reelle ejere fra Sogn.dk til Erhvervsstyrelsens register over reelle ejere”, 22 June 2023, https://erhvervsstyrelsen.dk/overfoersel-af-oplysninger-om-menighedsraadenes-reelle-ejere-fra-sogndk-til-erhvervsstyrelsens.

[33] Chapter 10a of LBK nr 1062 af 19/05/2021; Section 3 of LBK nr 1052 af 16/10/2019; Dahl and Castenschiold Paaske, Denmark: International Estate Planning Guide; Moran Harari, Andres Knobel, Markus Meinzer, and Miroslav Palanský, Ownership registration of different types of legal structures from an international comparative perspective: State of play of beneficial ownership - Update 2020 (Chesham: Tax Justice Network, 2020), https://www.taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/State-of-play-of-beneficial-ownership-Update-2020-Tax-Justice-Network.pdf.

[34] “Registrering af Trust”, Virk, n.d., https://virk.dk/myndigheder/stat/ERST/selvbetjening/Registrering_af_Trust/.

[35] Alanna Markle, Coverage of corporate vehicles in beneficial ownership disclosure regimes (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/coverage-of-corporate-vehicles-in-beneficial-ownership-disclosure-regimes/.

[36] Tymon Kiepe, Verification of beneficial ownership data (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2020), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/verification-of-beneficial-ownership-data/.

[37] To complete the registration, the person declaring the beneficial owner(s) will also need to disclose the beneficial owner(s)’ CPR number or equivalent unique identification for foreign owners. See: “Registrer ejerforhold for legale og reelle ejere”, Virk, n.d., https://virk.dk/myndigheder/stat/ERST/selvbetjening/Det_Offentlige_Ejerregister/vejledning-registrer-ejerforhold/; “eID in Denmark”, Agency for Digital Government, n.d., https://en.digst.dk/systems/mitid/eid-in-denmark/.

[38] “Get started with MitID”, MitID, n.d., https://www.mitid.dk/en-gb/get-started-with-mitid/; “MitID Erhverv for companies and associations”, MitID, n.d., https://www.mitid.dk/en-gb/mitid-business/.

[39] “Legitimation and documentation”, MitID, n.d., https://www.mitid.dk/en-gb/help/help-universe/mitid-user/legitimation-and-documentation

[40] “Danish Business Authority Increases Control with Foreign Addresses”, Carsted Rosenberg, updated 18 May 2021, https://www.carstedrosenberg.com/post/danish-business-authority-increases-control-with-foreign-addresses.

[41] Lord and Kiepe, Structured and interoperable beneficial ownership data.

[42] “Danish Business Authority Increases Control with Foreign Addresses”, Carsted Rosenberg.

[43] FATF, Best practices on beneficial ownership for legal persons.

[44] Christian Hattens, Beneficial ownership: Experiences from the Danish implementation of an Beneficial Ownership Register (Transparency International Denmark, 2022), https://transparency.dk/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/TI-Beneficial-Owners-Conference-report-Experiences-from-Denmark.pdf.

[45] LBK nr 1952 af 11/10/2021.

[46] FATF, Best practices on beneficial ownership for legal persons; Stk 3, Stk 4, LBK no. 1052 of 16/10/2019.

[47] Kiepe, Verification of beneficial ownership data.

[48] LBK nr 1062 af 19/05/2021, Section 15 a, Stk 2.

[49] The term “structured data” describes information that is collected and highly organised according to a structure that categorises different pieces of information into different fields. See: Lord and Kiepe, Structured and interoperable beneficial ownership data.

[50] Lord and Kiepe, Structured and interoperable beneficial ownership data.

[51] Tymon Kiepe, Making central beneficial ownership registers public (s.l.: Open Ownership, 2021), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/making-central-beneficial-ownership-registers-public/.

[52] “Danmarks Adresseregister (DAR)”, Danmarks Adresser, n.d., https://danmarksadresser.dk/om-adresser/danmarks-adresseregister-dar.

[53] Search results as consulted on 11 December 2023: “Unit view”, CVR - Det Centrale Virksomhedsregister, n.d., https://datacvr.virk.dk/enhed/person/4000550457/deltager.

[54] “System-til-system adgang til CVR-data”, CVR - Det Centrale Virksomhedsregister, n.d., https://datacvr.virk.dk/artikel/system-til-system-adgang-til-cvr-data.

[55] “Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (v0.3)”, Open Ownership, n.d., https://standard.openownership.org/en/0.3.0/.

[56] “Filudtræk på Datafordeleren”, Atlassian Confluence, updated 30 October 2023, https://confluence.sdfi.dk/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=16056696; Carlotta Carbone, Caterina Paternoster, Michele Riccardi, Maíra Martini, Adriana Fraiha Granjo, Andres Knobel, Manuel sur la transparence des bénéficiaires effectifs (s.l.: Civil Society Advancing Beneficial Ownership Transparency (CSABOT), 2020), https://transparency-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/CSABOT_Handbook_FR.pdf.

[57] “Vilkår og betingelser”, CVR - Det Centrale Virksomhedsregister, n.d., https://datacvr.virk.dk/artikel/vilkaar-og-betingelser.

[58] “Vilkår og betingelser”, CVR - Det Centrale Virksomhedsregister; ; “Reklamebeskyttelse”, CVR - Det Centrale Virksomhedsregister, n.d., https://datacvr.virk.dk/artikel/reklamebeskyttelse.

[59] Erhvervsstyrelsen, Vilkår for brug af danske offentlige data (Copenhagen: Erhvervsstyrelsen, 2015), https://assets.ctfassets.net/kunz2thx8mib/1DF9gunsCPZ0BQvEK2dA2x/22251dd30fcb8b7762646d51ff60564f/vilkaar_for_brug_af_danske_offentlige_data_v4.pdf.