A brief assessment of the usability of Norway’s beneficial ownership register

The Brønnøysund Register Centre, which manages Norway's beneficial ownership register (Source: BYGG Tech AS).

Following the launch of Norway’s beneficial ownership (BO) register in October 2024, Tax Justice Norway (TJN) obtained access credentials to the BO register’s application programming interface (API) on the basis of legitimate interest. At TJN’s request, Open Ownership provided technical support to connect to the register, automate information retrieval, and assess the data’s usability. This piece summarises the key findings of that analysis. [1] It shows that Norway’s BO register provides well-structured and clearly organised data and offers strong foundations for analytical use. At the same time, the analysis finds that analytical potential is constrained by a number of policy and technical design choices, with Norway taking a more privacy-cautious approach than several European Union (EU) Member States. Finally, the piece outlines what works well, identifies the key usability gaps, and proposes practical improvements that could substantially increase the usability and impact of Norway’s BO data while maintaining strong policy safeguards.

Ten years in the making

Norway’s BO register of legal entities was officially launched in October 2024, nearly ten years after it was approved by Parliament in 2015. The register has been established to “counter money laundering, terrorist financing, and economic crime”. Initially envisioned as a public and open register, its implementation was repeatedly delayed due to both technical challenges and legal uncertainty arising from the November 2022 Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruling. The court ruled that the provision in the EU’s fifth anti-money laundering (AML) directive, which provided for indiscriminate public access to BO information for AML purposes within the EU, was legally invalid. While not a member of the EU, a lot of EU legislation is adopted by Norway as a member of the European Economic Area, including the EU’s fourth and fifth AML directives. Consequently, Norway postponed its planned 2023 launch and restricted access to specific groups. Those covered in the access framework include: authorities with statutory powers as well as those with a legitimate interest, such as journalists, researchers, civil society organisations (CSOs); and entities obliged to conduct customer due diligence under AML rules, including banks and real estate professionals.

Accessing Norway’s beneficial ownership register

The Norwegian BO register is accessible only through a software interface (API). Access requires prior registration and technical setup through Samarbeidsportalen and Maskinporten, the national authentication gateways. While this design ensures secure and controlled access, it also creates barriers for smaller organisations without dedicated technical capacity; for example, the register does not have a search function. A consultation on access to the register, held in September 2024, indicated that the API-only model allows the Brønnøysund Register Centre to centrally approve and authenticate users. This approach is anchored in the law, which requires authorised users to “adapt to the registrar’s technical solutions” (“tilpasser seg registerførers tekniske løsninger”) and ensures that access rights are verifiable.

The law also states that access for users other than public authorities cannot involve extracting data from the register or searching for natural persons. The policy rationale for this can also be found in the consultation, which proposed that searches for natural persons can only be made by public authorities, as:

[...] the interconnection of registers of beneficial owners at European level (BORIS) [...] is based, among other things, on the fact that only public authorities can perform searches on natural persons.

The Ministry of Finance also takes into account the assessments of the European Court of Justice in the Sovim decision, which limits public access to personal data. Currently, the Ministry is not confident that there is sufficient basis for providing access to the aggregated extract of the register of beneficial owners – and thus searchability of natural persons – other than to public authorities. The Ministry emphasises that this may be considered at a later date, especially in light of other changes that may be necessary as part of implementing the new AML package.

The consultation proposes that those who access the register find information about the beneficial owners of legal entities by searching for the legal entity using the company number.

While the consultation points to the discussions and developments in the EU, Norway appears to have taken a more cautious approach than some EU member states, such as France, which have already launched new access regimes in line with the post-CJEU judgement AML Directive.

Methodology and setup

To retrieve and assess the BO register’s data, we followed a structured process aimed at establishing secure access, authenticating connections, and evaluating data usability.

Step 1: Access setup

- TJN registered in Samarbeidsportalen, Norway’s government collaboration portal.

- Registration provided a Client ID, Key ID, and private key, which would be needed for authentication.

- The access scope was configured based on TJN’s legitimate interest, as permitted for CSOs.

- TJN obtained written consent from the registrar to share their credentials with Open Ownership for testing purposes.

Step 2: Authentication and connection

- Authentication was performed using the registered credentials via Maskinporten for secure public API access.

- Each session generated a short-lived access token to limit repeat queries and control extraction volumes.

- The token was managed directly through a Python notebook to maintain secure authentication.

- Queries to the BO register’s API retrieved BO information in structured JSON format and could only be made using company numbers.

Step 3: Usability testing

- Company identifiers for testing were retrieved from the Enhetsregisteret, the Norwegian register of legal entities, which provides a public bulk download containing corporate registration details of all listed active and dissolved entities.

- With these identifiers, the usability, completeness, and structure of the BO register data were assessed.

Usability assessment and analytics

The usability of the Norway BO register was evaluated by piloting Open Ownership’s Usable BO data framework, focusing on four core categories of features: search, delivery, content, and scope. The existence in the register of each feature was judged to be either present, partially present, or absent. The analysis examined both technical accessibility (e.g. API structure, authentication, and bulk delivery options) and data quality (e.g. field completeness, identifiers, and relationships). The main findings are summarised in Table 1.

The assessment found that the register provides structured and well-formatted data through a stable and functioning API. Importantly, the system’s use of authoritative company identifiers and standardised formats enhances interoperability and facilitates integration with other open registers, such as the Enhetsregisteret or politically exposed person (PEP) datasets. In addition, maintaining both up-to-date and historical records is a critical feature that supports longitudinal and retrospective analysis, allowing users to trace ownership changes over time.

However, usability for large-scale analysis remains limited by restricted search functionality, a lack of bulk access, and an absence of unique identifiers for individuals. The API allows searches only by company number not by company name, beneficial owner name, or other personal attributes, and it lacks both free-text and filtering options. In practice, this means that users must strategise when searching by attributes other than company number. For example, users starting with company names must first query the Enhetsregisteret database to find company numbers corresponding to company names, then use those numbers to retrieve data from the BO register.

While bulk access is not available, it is theoretically possible to compile a complete dataset by downloading the full list of company numbers from the Enhetsregisteret and running automated API queries across all of them. This approach is technically feasible but highly time consuming, producing only a partial snapshot of the register in a given moment, or a composite of slightly different moments across companies, depending on the query duration. This situation illustrates a key trade-off: if access restrictions were introduced for privacy reasons, they can still be circumvented through automation. In practice, the only thing preventing a user from doing this is the law, although it remains unclear whether compliance will be proactively monitored or enforced through the API. At present, there are no specific terms of use governing the API.

Lastly, the absence of unique identifiers for individuals limits the ability to cross-reference records with other datasets and hinders effective disambiguation. Currently, only public authorities can access the register’s complete inventory or search using national identity numbers. To enhance usability while safeguarding privacy, a straightforward and feasible approach could involve introducing hashed or register-specific identifiers for individuals, or other encrypted person-level references. Such mechanisms would enable entity resolution and verification across datasets without disclosing personal information.

Table 1. Strengths and gaps in the usability of the Norway beneficial ownership register

| Strengths | Gaps |

|---|---|

|

✓ Stable API and interoperability The API supports repeated queries by company ID, allowing connection with other open registers (e.g. Enhetsregisteret, PEP datasets) to expand analytical scope. |

✗ No public interface There is no public search portal or web-based access, so technical setup and knowledge are required, which journalists or CSOs may lack. |

|

✓ Structured and well-formatted data Data is returned in machine-readable JSON format, facilitating integration with analytical tools. |

✗ Restricted bulk access Access to BO information is available only through the API, with no public bulk download option. |

|

✓ Comprehensive data details Contains personal information and relationship attributes that enable meaningful analytics. |

✗ Limited search functionality Queries are restricted to company number; no free-text or beneficial owner search options are available. |

|

✓ Authoritative company identifiers Uses official company numbers from the Enhetsregisteret, ensuring interoperability across datasets. |

✗ No unique identifiers for individuals Individuals cannot be uniquely distinguished, which limits disambiguation and linkage. |

|

✓ Legal ownership and intermediary coverage Captures both direct and indirect relationships, and Norwegian intermediary entities are explicitly reported. |

✗ Missing relationship timestamps Start and end dates for ownership links are not included, reducing temporal accuracy; no change alerts are provided. |

|

✓ Standardised attributes Adopts ISO 3166 country codes and standard date formats. |

✗ Limited documentation No formal data dictionary, detailed field description, or terms of use are provided. |

|

✓ Up-to-date and historical data available Includes both current and past ownership relationships, clearly marked with status flags. |

✗ Incomplete disclosure information Missing details on disclosing parties and exempt or noncompliant entities. |

Analytical implications

The BO register’s current search functionality is limited to queries by company number, which significantly restricts the types of analytical questions that can be addressed. Under this setup, it is not possible to compile overall descriptive statistics or perform aggregate analyses across the full dataset. When a predefined list of companies is available, users can generate descriptive statistics for that subset. Otherwise, users can only explore company-specific queries, preventing more complex, policy-oriented analyses, as illustrated below.

Table 2. Analytical scope under current access setup

| Query posed by Tax Justice Norway | Possible to answer directly using the API | Requires bulk access |

|---|---|---|

| How many beneficial owners are associated with a given company (identified by company number)? | ✓ | ✗ |

| Are these relationships direct, or do they involve intermediaries? | ✓ | ✗ |

| Which entities act as intermediaries in indirect links to a given company? | ✓ | ✗ |

| How many Norwegian beneficial owners and companies are there in the register? | ✗ | ✓ |

| How many non-Norwegian beneficial owners are based in high-risk jurisdictions? | ✗ | ✓ |

| How many companies are owned by individuals from a particular country, and in which sectors (including their NACE (statistical classification of economic activities) codes)? | ✗ | ✓ |

| What share of companies are owned by individuals from Norway, the EU/European Free Trade Association, or elsewhere? | ✗ | ✓ |

| Which five countries account for the largest number of foreign beneficial owners? | ✗ | ✓ |

| Which beneficial owners control the largest number of companies? | ✗ | ✓ |

| What companies have the highest number of beneficial owners? | ✗ | ✓ |

If bulk access were available, the register’s structured data could support a wider range of analytical metrics and risk assessments beyond company-level queries. For ownership complexity, indicators such as maximum chain length, multiple intermediaries, or unusually high numbers of beneficial owners could signal attempts to conceal control. For jurisdictional exposure, metrics might include the proportion of companies with cross-border ownership links, connections to high-risk jurisdictions, or mismatches between nationality and residence of beneficial owners. Anomalous patterns could be identified through missing or undeclared BO data, incomplete records, or implausible ages of beneficial owners. Together, these metrics would help detect opacity and weak verification processes, providing a practical framework for red-flagging risks.

Approach to ownership networks

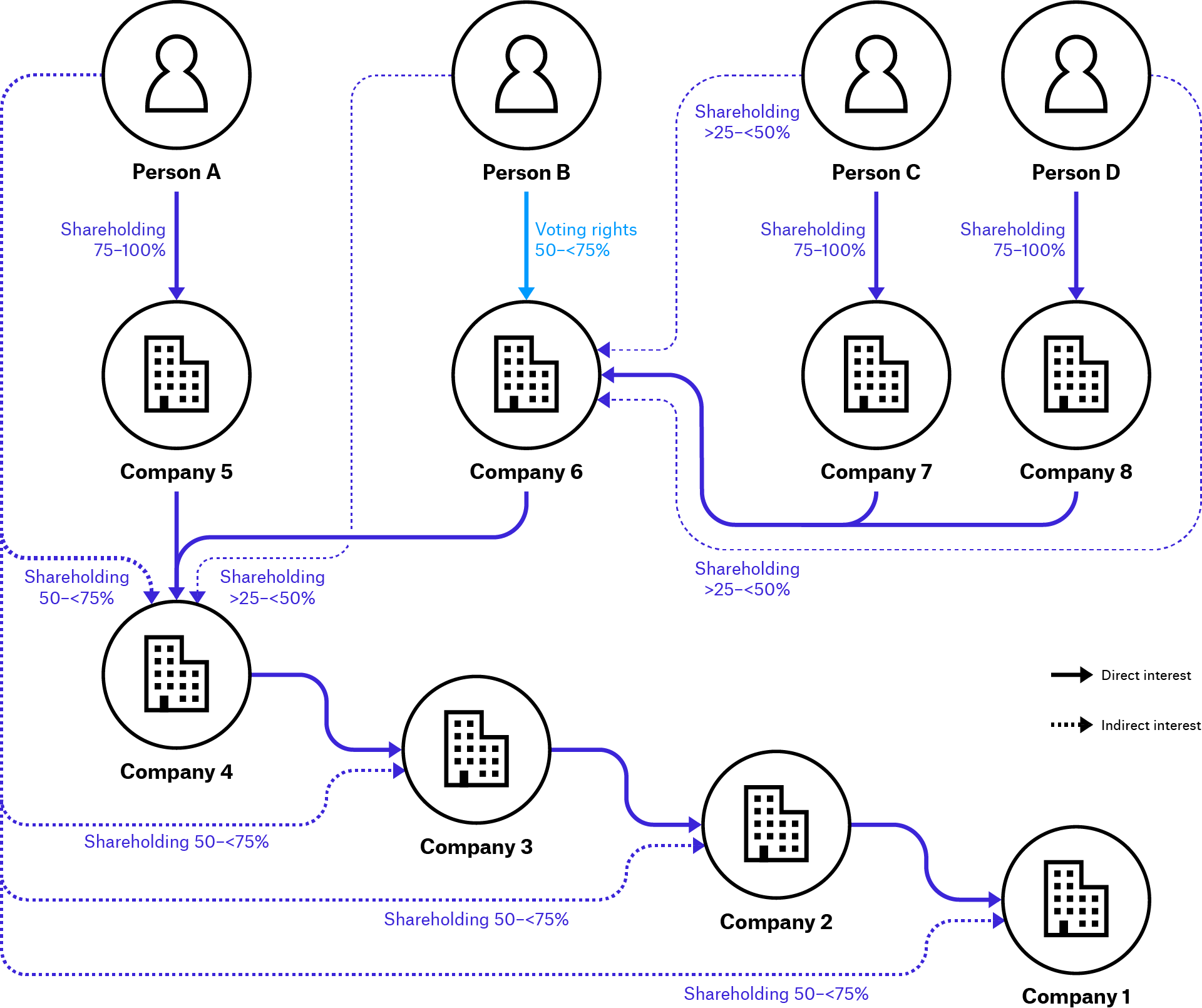

Research on the use of BO information shows that many use cases across different policy areas require understanding details about intermediaries in BO networks, including in public procurement, customer due diligence, asset recovery, and taxation. The register introduces a comprehensive approach to capturing information on BO networks, including details on intermediaries involved in indirect relationships. When looking up a company’s beneficial owners, the results indicate whether each relationship is direct or indirect and, in the latter case, identify the intermediary companies through which the BO interest is held.

The regulations state that “when the position is held indirectly, the organization number of all intermediate legal persons, entities, associations, and arrangements must be registered. If these do not have a Norwegian organization number, the company name and foreign organization number must be registered. If these do not have a foreign organization number, the company name and address must be registered”.

Table 3. Example of indirect ownership chain (anonymised) in Norway’s register

| Company number | Beneficial owner name | Interest type | Level of interest | Interest nature | Norwegian intermediary company numbers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Person A | Shareholding | 50–<75% | Indirect | 2, 3, 4, 5 |

In this example (Table 3), where the identity of the beneficial owner and the company numbers have been anonymised, the relationship between the company and the beneficial owner is indirect, and the intermediary companies involved are listed. Using these company numbers, it is possible to look up each intermediary company and reconstruct the ownership network step by step.

Table 4. Ownership information of intermediary companies (anonymised) in Norway’s register

| Company number | Beneficial owner(s) | Interest type | Level of interest | Interest nature | Norwegian intermediary company numbers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Person A | Shareholding | 50–<75% | Indirect | 3, 4, 5 |

| 3 | Person A | Shareholding | 50–<75% | Indirect | 4, 5 |

| 4 |

Person A Person B |

Shareholding Shareholding |

50–<75% >25–<50% |

Indirect Indirect |

5 6 |

| 5 | Person A | Shareholding | 75–100% | Direct | N/A |

| 6 |

Person B Person C Person D |

Voting rights Shareholding Shareholding |

50–<75% >25–<50% >25–<50% |

Direct Indirect Indirect |

N/A 7 8 |

| 7 | Person C | Shareholding | 75–100% | Direct | N/A |

| 8 | Person D | Shareholding | 75–100% | Direct | N/A |

By combining this information, it becomes possible to understand that Person A holds an indirect interest in Company 1 through several intermediary entities, while Persons B, C, and D appear at lower tiers within the BO network. The resulting network, illustrated in Figure 1, shows the relationships between different intermediaries.

Figure 1. Ownership network reconstructed using intermediary company information

Thus, Norway’s approach provides a better understanding of BO networks than systems that do not distinguish between direct or indirect relationships (such as in the United Kingdom (UK)) or omit intermediary information (such as in the Philippines).

Most often, only the company number is collected for intermediaries, especially when they are Norwegian companies. This reduces the duplication of information collected to some degree. However, it is not always possible to understand the relationships between different companies. As such, Figure 1 is based on assumptions. Although this analysis did not find any instances of information on foreign intermediaries being collected, understanding full networks in those cases will depend on the access provisions of the registers of those countries.

However, the system collects duplicate information on beneficial owners – such as Person A in Figure 1 – which may lead to data conflicts, particularly when information is submitted at different times within the 14-day statutory reporting period following a change in ownership. This duplication also increases the compliance burden for companies. By contrast, in the UK’s approach, when the parent company of a declaring company holds a significant stake in it and is a UK company itself, the declaring company only needs to submit information on the parent company. This reduces the compliance burden, as well as the duplication of information collected and the likelihood of potential conflicts. However, it may also reduce opportunities to cross-check declarations for verification. In the future, the integration of Norway’s new coordinated shareholder register may help plug these information gaps and reduce duplication, enhancing both data quality and reporting efficiency.

Key takeaways and the road ahead

Norway’s BO register is a technically robust system aligned with recognised data standards. It uses official company identifiers, provides structured data with both up-to-date and historical records, and integrates with national open data infrastructure, providing a solid foundation for interoperability and analytical use.

However, its analytical potential remains limited by design choices that prioritise privacy and control over accessibility. The lack of unique identifiers for individuals, restricted search functions, and absence of bulk download capabilities create barriers to efficient large-scale analysis and reuse, particularly for smaller organisations without dedicated technical capacity. While privacy concerns raised at the EU level explain this caution, Norway appears to be more restrictive than several member states that have already introduced new access provisions in line with the post-CJEU framework. It can be argued that Norway’s approach is overly cautious, to the extent that certain analyses relevant to countering money laundering, terrorist financing, and economic crime are not feasible, undermining the very purpose and impact that legitimate interest access is intended to achieve.

Applying Open Ownership’s Usable BO data framework made it possible to systematically identify these enablers and constraints, offering a replicable approach for assessing BO data usability across contexts. The Norway case demonstrates how data design decisions directly shape the analytical reach and public value of BO systems.

Looking ahead, Norway’s broader open data ecosystem – including publicly available sources, such as Enhetsregisteret data and PEP information on ministers and members of parliament – creates favourable conditions for future interoperability and integrated analysis. The BO register could contribute more effectively to this ecosystem through targeted improvements, such as introducing controlled bulk access, enriching metadata with unique identifiers for individuals, and enhancing documentation. Implementing privacy-preserving identifiers, such as hashed or register-specific person IDs, would also enable linkage and verification across datasets without disclosing personal information, all of which could substantially increase usability while maintaining privacy safeguards. Together, these measures would strengthen civil society and research-driven analysis while advancing the broader goal of using BO data to enhance transparency, accountability, and risk detection, supported by responsible data governance.

Footnotes

[1] For TJN’s analysis, please see: Rapport: Skjult eierskap i Norge (November 2025).

Related articles and publications

Publication type

Blog post

Country focus

Norway

Sections

Research

Open Ownership Principles

Central register