Considerations for creating a global register to support better international tax cooperation

Photo by Clint Adair on Unsplash.

To improve policies and close the tax gap, tax authorities need to understand the relationships between individuals, corporations, and assets. Many see the negotiations of the United Nations Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation (UNFCITC) as an opportunity to build on the momentum driving beneficial ownership transparency reforms as well as to strengthen how governments use and share information about beneficial owners – that is, those who ultimately own and control wealth and assets.

The UNFCITC’s terms of reference include the effective taxation of high-net-worth individuals. To do this, authorities need to know who these individuals are and which taxable assets they own, including in other jurisdictions and through networks of legal vehicles. Authorities need to know the identities of and relationship between two parties in a transaction who may or may not be in the same country to achieve the Convention’s aim of combatting illicit financial flows, as well as tax avoidance and evasion. In order to realise the UNFCITC’s aspirations, tax authorities must understand the networks of relationships between individuals, legal vehicles, and assets, including across borders. The term beneficial ownership networks refers to these interconnecting relationships.

This piece sets out key considerations for connecting information to understand transnational beneficial ownership networks. It begins by describing the current, fragmented global landscape of beneficial ownership information and the challenges of understanding transnational ownership networks, both for tax purposes and other use cases. It then discusses approaches to creating a global register, drawing on Open Ownership’s experience developing and managing a prototype global register, a prototype single-search register, research, and previous thinking. Ultimately, this piece argues that any solution will require investing in better information infrastructure at the national level, including the delivery of comprehensive and effective registers, as well as providing real-time access and interconnecting information sources.

Open Ownership developed and managed a prototype global beneficial ownership register of companies for seven years.

Current situation

Research on the use of beneficial ownership information shows that many use cases across different policy areas require understanding details about intermediaries in beneficial ownership networks, including in public procurement, customer due diligence, asset recovery, and taxation. Therefore, while the thinking in this piece on how to understand beneficial ownership networks within and across borders can help shape the discussions around the UNFCITC, its relevance extends beyond this to the future of these reforms more generally.

Currently, information about beneficial ownership networks is fragmented. Beneficial ownership information is predominantly collected and stored at the national – and sometimes sub-national – level. Understanding transnational beneficial ownership networks can be a challenging, costly, and time-consuming process. Information can be missing and it may not be possible to see the whole picture.

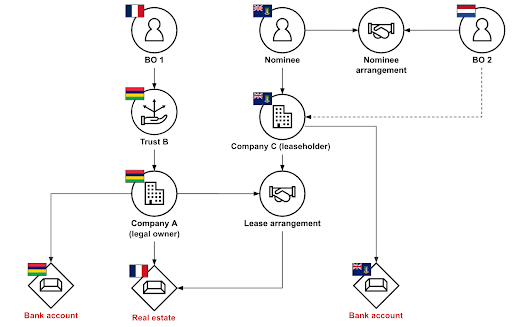

An illustrative example of a beneficial ownership network.

Information typically collected in beneficial ownership declarations for legal entities. Direct relationships are represented by solid lines, and indirect relationships are demonstrated by dotted lines. Beneficial ownership registers for legal vehicles collect information about direct and indirect relationships, with varying degrees of detail on the intermediaries (direct relationships) which comprise this indirect relationship. Different registers capture different information about beneficial ownership networks, often with considerable overlap.

To tackle these challenges, various parties have been calling for a global asset register or a global beneficial ownership register. The Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation (ICRICT) was one of the first to propose this idea. This gained more prominence during the 2024 G20, where civil society organisations presented the idea of a global asset register as part of the solution to effectively tax wealth in order to reduce inequality.

In 2025, the fourth Global Conference on Financing for Development’s Compromiso de Sevilla – approved in July in Seville and endorsed at the UN General Assembly in August – commits to “enhance mechanisms for information exchange among national beneficial ownership registries and consider the feasibility and utility of a global beneficial ownership registry”.

Global asset register vs. Global beneficial ownership register: Definitions and terminology

Although the terminology may differ, there is considerable conceptual overlap in the discussions around a global asset register and a global beneficial ownership register: fundamentally, they both aim to shed light on transnational beneficial ownership networks. To illustrate, ICRICT defines a global asset register as “a comprehensive global registry that links all types of assets, companies, and other legal vehicles used to own assets, to the persons that really own or controls – or benefits from – them, the so called ‘beneficial owners’”. The Compromiso de Sevilla mentions a global beneficial ownership registry, but is not specific about which types of legal vehicles or assets will be covered. The concepts are therefore similar, if not the same. This piece will use the term global register.

The topic of a global register is likely to remain salient during the UNFCITC negotiations. As a more complete understanding of beneficial ownership networks helps enforce tax compliance (as recently explored in an Open Ownership policy briefing), a global register could benefit both lower and higher-income countries. Countries everywhere face pressures on national budgets, whether due to increased defence spending and borrowing costs, or official development assistance cuts, so there is a broad case to be made for this policy issue.

What is a register?

At its simplest, a register is an official record containing regular entries. Government registers can fulfil different functions and often involve the presentation of relevant documentation or evidence. In some contexts, the very act of making an entry in a register can have a legal effect. For instance, registration is often part of the process of incorporating a new company, providing it with a separate legal personality, and limiting its shareholders’ liability. The entry of that company on the register provides legal certainty of that company’s existence. A company register may have an objective to be transparent about some of the information it holds, for example, to protect the rights of shareholders, hold companies to account, or stimulate growth.

A register usually facilitates access for various people and systems from a single point. A register can collect information or collate information from other registers. In the latter case, a register can be referred to as a secondary register, collating information from primary registers. Primary registers are the main source of the information contained in it, whereas secondary registers are composed of other sources of information. Registers may also be an authoritative source of information, and the information contained in the register may give legal certainty and be legally enforceable. For example, as part of digital public infrastructure (DPI), registers aim to be reliable and centralised sources of verified information that form the backbone of shared and interoperable digital government systems, and thus play a crucial role in enabling efficient and effective public service delivery. In these cases, registers should constitute a single, current, and reliable source of data – a single source of truth. This implies that they should not hold any conflicting information. To reduce both issues of data fragmentation, redundancy, conflicts, and compliance burden, registers may implement a once-only principle, where information is only submitted to authorities once.

Approaches to creating a global register

A global register could use a number of approaches. There seems to be consensus that a global register should provide a centralised access point for information. A separate decision is how centralised the submission of information should be. This could range from highly centralised, by a supranational register handling the submission of information; to decentralised, where jurisdiction-level registers handle the submission of information, which is subsequently collated; or a combination of both.

A supranational register

Beneficial ownership transparency reforms world-wide are typically nationally organised, predominantly through the implementation of registers of beneficial ownership information for legal vehicles. Any supranational solution to collecting information – where parties would submit information directly to a register spanning multiple jurisdictions – would need a significant amount of political support, and would likely encounter significant practical barriers. A supranational register may also risk being very narrow in its scope, such as only focusing on a subset of high-risk assets or companies. Nevertheless, it merits briefly exploring what a transnational solution could look like.

One example of a supranational global register is the International Maritime Organisation’s (IMO) Global Integrated Shipping Information System (GISIS). Certain vessels need to register with the IMO, and information about these vessels – including ownership information – is stored and accessible in the GISIS.

The type of information is also submitted to vessel registers at the national level. The act of registration with national vessel registers confirms the vessels’ identity and allows them to fly the flags of the registry state, and can be considered the primary registers for this information. These national registers lack standardisation in the information they collect and share. The IMO does not cross-check information with these registers, and it would be technically challenging to do so. Because of this, although the GISIS collects standardised information, ownership information is missing for many entries. Given the lack of enforcement and verification, as well as the different understandings and definitions of the term beneficial ownership, the accuracy of all listed entries can be questioned.

Moreover, there is an added compliance burden, as vessel owners need to submit information both at national and supranational levels – as well as, often, to regional fishing management organisations – all with potentially different definitions of beneficial ownership, which increase the chance of accidentally inaccurate submissions. Therefore, there is a likelihood of duplication and redundancy of information between these different levels, and also of inconsistency. The challenge with duplication or overlap in data collection is that unless information is compared and consolidated, it cannot be authoritative and reliable. In this case, if there is contradicting information between the GISIS and a national register, it is difficult to know which to trust.

Being an authoritative source of information would be an ambitious but highly useful objective of a global register. A challenge will be that a supranational register like the IMO register does not have the same legal effect as the primary national registers, and is therefore less likely to be accurate, up to date, and authoritative. For such a register to be authoritative, it would require consistent definitions and to minimise duplication with primary registers. This could be achieved by: retrieving information from these registers; (partly) replacing these registers so a supranational register becomes a primary register (this is unlikely, given the fact that registration for legal vehicles and assets happens at the sub-national or national level); or a combination.

One advantage of the GISIS is that it assigns permanent identifiers, which remain the same, while national identifiers may change as ships change flags. Nevertheless, given both the challenges and the work already done at the international level, it is unsurprising that the ICRICT and others have advocated for a solution combining national or regional registers of beneficial owners of legal vehicles. The Compromiso de Sevilla notes that it “will enhance mechanisms for information exchange among national beneficial ownership registries and consider the feasibility and utility of a global beneficial ownership registry. In all these efforts, we will build on existing work”, suggesting combining existing sources is the likely approach to a global register.

Leveraging existing information in national registers

Beneficial ownership networks can span multiple jurisdictions which are separately collecting information. Because information is collected about indirect relationships, information about the same relationships and intermediaries is collected at different points and at different times in declarations for different legal vehicles in a network. This poses a key challenge to understanding these networks.

The collection of overlapping information can also happen within a single jurisdiction, for example:

- where a company has to submit both its shareholders and its beneficial owners (who are also shareholders) separately to a central shareholder register and to a beneficial ownership register for companies;

- where two domestic companies that are part of the same network both submit information about their beneficial owners in separate declarations; or

- where a company and trust are in the same network and declare information about their owners and parties to the trust to different registers.

This overlap may lead to conflicts and may pose challenges for users. For example, how will the user know if the information differs because of accuracy issues or because it was declared at different points in time?

Within a single jurisdiction, it is easier for information to be used to either exempt a party from submitting information (e.g. the United Kingdom’s relevant legal entities approach) or to help compare and consolidate overlapping information which can support verification processes (e.g. seeing whether centrally held shareholder information corresponds to beneficial ownership information). [1] Where these relationships span across borders, the legal frameworks, definitions, and amount of detail and information collected about these relationships will differ (for instance, from simply collecting the fact that an indirect relationship exists, to collecting information on all intermediaries involved in the relationship). Depending on how authoritative a register seeks to be – whether national or supranational – it will need to minimise or resolve data conflicts when joining information together.

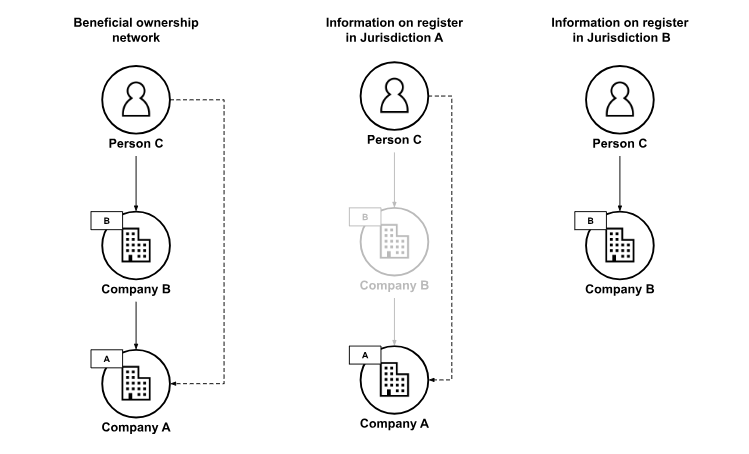

To illustrate, consider the diagram below, in which Company A in Jurisdiction A is fully owned by Company B in Jurisdiction B, which is owned by Person C in Jurisdiction C. Company A will be declaring information about Person C’s indirect interest in the company and thereby inherently provide information about the network involving Person C’s relationship with Company B, possibly also with specific details. The company register in Country B will also be collecting information about this relationship, so there will be overlapping – and potentially conflicting – information held about this beneficial ownership network in Country A and B.

The company register in Jurisdiction A could be considered a primary register for information about Company A (and its relationship to Company B) and other companies in that jurisdiction. At the same time, Country B’s company register can be considered the primary register for Company B and other legal vehicles in that jurisdiction. However, the register in Country A will end up holding information about the network, including Company B and its relationship to Person C in its register, for which it is not the primary register. By design, a beneficial ownership register holds a significant amount of information for which it is not the primary register.

The register in Jurisdiction A and Jurisdiction B will hold overlapping information. The register in Jurisdiction A may collect details on shareholder or intermediary relationships, but at minimum it will collect some information about the relationship between Person C and Company B.

If information from both jurisdictions is combined and connected in a multi-jurisdiction register, the register could hold duplicate and potentially conflicting information about the network. This will make it difficult to gain an accurate understanding of all the intermediaries in a network, and the information will be less reliable. However, even if these conflicts are not resolved, this register will still be useful, as evidenced by Open Ownership’s testing of a prototype single-search tool for multiple registers with users. Simply being able to access information from multiple different jurisdictions in a single place already takes away significant barriers faced by many data users. The various declarations will still help to know who said what when.

To illustrate, the European Union (EU) started gradually interconnecting beneficial ownership registers in 2015 through the Beneficial Ownership Registers Interconnection System (BORIS). While interconnection is in the name, in practice the BORIS platform seems to be more of a search engine for siloed national registers. For example, users can only search by company name, then receive results for the search in different member states. There is no entity resolution for individuals, meaning it is not possible to easily see whether or not multiple records refer to the same person.

When the portal was publicly accessible in 2022, it only provided information about companies’ beneficial owners, and had no information about intermediaries or legal arrangements. However, the 2024 EU Anti-Money Laundering Regulations require “a description” of the network in case of indirect relationships, including “identification numbers of the individual legal entities or legal arrangements that are part of that structure, and a description of the relationships between them, including the share of the interest held”. If this information is collected by member states in a structured way with reliable identifiers, they may only have to collect information on direct relationships for networks that span the EU. BORIS could then join and append this information, with entity resolution for the different intermediaries, and the EU would be closer to creating a single regional view of beneficial ownership networks by automatically combining information from primary registers. This would be more authoritative and reliable, more useful, and easier than the resource-intensive task of consolidating information about full networks and resolving the conflicts that ensue from overlapping data. [2] However, for this to be achievable, there must be an alignment in and interconnection of the information collected, so the utility of this approach outside regional blocs such as the EU may be limited.

Alternatively, users of BORIS from each jurisdiction could go through the exercise of joining and appending information as well as entity resolution themselves. However, this would be duplicative and resource intensive. The technical skills required could mean that many users would need to resort to expensive solutions. In this approach, the private sector would likely play a significant role. The private sector is already providing some such services within the EU and beyond, albeit with incomplete coverage and using a variety of information sources with varying accuracy and reliability. Experience shows that the cost of these services precludes some users from accessing and using data.

Collecting better information about direct relationships

To combine national information into a global register that is a reliable and authoritative source, overlapping information will need to be resolved. This may require starting from the bottom-up: rethinking the approach to data collection at the level of jurisdictions and primary registers. Given the challenges in resolving overlapping information, a potential solution could involve reducing the collection of information by shifting towards registers collecting better information about direct relationships – the relationships between people, legal vehicles, and assets, without any other people or legal vehicles as intermediaries. This includes information on shareholders, partners, and nominees – the latter of which a number of jurisdictions are already starting to collect in light of the 2022 Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendation 24 revisions. This would significantly reduce duplication and the compliance burden. Where the incorporation of legal entities happens, relevant information is already maintained and collected, and often submitted to one or more government agencies. Combining this information sheds light on intermediary actors in networks.

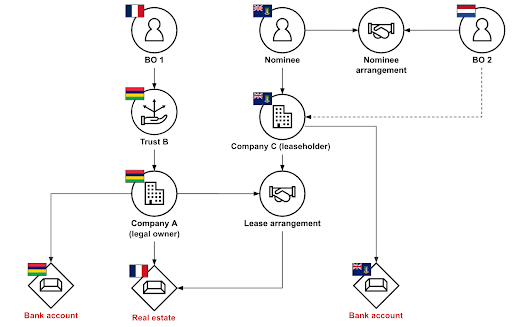

Focusing on direct relationships will also help meet other user needs, including by improving accuracy, raising compliance while decreasing the compliance burden, and enabling easier standardisation. [3] For example, the FATF defines the beneficial owners of a company that is party to a trust as also being the beneficial owners of the trust. With improved information-sharing between registers, for these interests trustees would only have to declare direct interests in (i.e. the parties to) the trust to a trust register – in this case, the name of the company. If this information is combined with information from the beneficial ownership register for legal entities, users could understand the full network, including parties – the individuals, the company, and the trust – and the direct and indirect relationships between them. [4] While the information is collected separately, a central register could ensure these records are combined for ease of access and use.

This general approach may also make it easier to connect information about legal vehicles and assets, as asset registers would only need to focus on collecting high-quality information on specific, defined direct relationships. Some of this information (such as registration of land or real estate ownership) confers legal rights and enforceability, and therefore has a higher likelihood of being accurate and is easier to verify. However, if all asset registers also start to collect information through beneficial ownership declarations, this will lead to even more duplication; higher costs of resolving this duplication; questionably accurate information that is difficult and costly to verify; and a higher compliance burden.

Continuing the example from earlier, a French real estate register would focus on collecting information about direct relationships relevant to the asset, including Company A (the legal owner) and Company C (the leaseholder).

Therefore, it may be a productive step forward to consider all information about beneficial ownership networks – including sources of information on direct relationships – as information relevant for beneficial ownership transparency and a global register, rather than simply the information currently collected in beneficial ownership declarations from legal vehicles. A global solution which incorporates more information about direct relationships would minimise duplication and associated costs.

This approach to understanding beneficial ownership networks would highly depend on effectively sharing information across borders. Declarations about indirect relationships at the national level could be scaled down as data-sharing improves. Conversely, declarations about indirect relationships may need to stay in place to cover non-cooperative jurisdictions and certain types of interests, such as certain types of influence or control. There may also be less privacy infringement associated with sharing information about direct relationships.

Sharing and combining information

Any solution to understanding transnational beneficial ownership networks – whether simply allowing for a standardised search of various national registers, or a more ambitious solution that truly interconnects information – will rely on effectively sharing information across borders. Ideally, the solution would enable centralised access to information that is automatically and directly combined from comprehensive national registers, rather than the more manual or periodic exchange of information which has been a common mode for international information exchange to date.

Direct access through a centralised platform would allow users to access the information they need when they need it (either directly if information is held on the platform, or the platform could enable access to national registers). This means users do not have to rely on the intervention of another party every time they access information (in the case of exchange on request), or information being exchanged only at set points in time (in the case of automatic exchange). This information should be structured and include reliable identifiers so it can readily be used and combined.

For example, information – including about beneficial owners and their financial assets – under the Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development (OECD)’s Automatic Exchange of Information mechanism is shared annually, in bulk, between jurisdictions. Because it is shared annually, it may be difficult to get an up-to-date snapshot or understand changes over time, which is often necessary for tax use cases. It is also not possible to proactively see if other jurisdictions hold information about a jurisdiction’s taxpayers. For this reason, the OECD has explored directly connecting beneficial ownership registers to asset (real estate) registers, as an alternative to periodic exchange.

The sharing of and access to information will need to be legally anchored with a stated purpose. The Compromiso de Sevilla mentions a global register in the context of tax cooperation, whereas the EU’s BORIS is focused on anti-money laundering. For any multi-jurisdictional register – regional or global – there should be clarity and consensus on its purpose, whether specific or broad, as this will inevitably determine access. For example, a global register for tax purposes may not be accessible or usable by other government or non-government investigators of other financial crimes or corruption.

If a global register were to be created, it raises all sorts of questions as to who would be responsible for its governance, and how it would be financed. This could become highly politicised, as could specific processes such as deciding on who has access, what they have access to, and how flexibly they can use the data (e.g. bulk access to the full dataset versus allowing for search by a limited set of fields). If there is consensus on the purpose of such a register being for international tax cooperation, some may suggest a party like the OECD would be logical, particularly given the focus. However, others will argue that this will not be sufficiently inclusive and representative. Perhaps the UNFCITC negotiations will shed some light on these questions.

Concluding thoughts and next steps

The Compromiso de Sevilla and the UNFCITC negotiations suggest that it is likely that discussions about a global register will ramp up over the next few years, and that this will build on existing national efforts. Key points in those discussions will be establishing consensus on the rationale and purpose of the register – and, connected to this, who should have access to the information – what the level of ambition is to connect existing information sources, and how reliable and authoritative this register will seek to be.

Any solution will require investing in better information infrastructure at national levels and moving from information exchange to enabling real-time access, aggregation, and entity resolution. This may also require exploring ways to reduce compliance burdens and duplication of information, which may involve the collection of better information about direct relationships. Naturally, any solution will involve trade-offs. [5] Consultation with users – those providing information, those ultimately using the information, and those overseeing the collection and sharing systems – should guide answering these questions.

User research will help explore whether it is worth investing in a truly interconnected solution, or rather a simpler approach that enables more direct and easier access through a central access point to national or regional registers (which are perhaps somewhat aligned but not fully interconnected). The latter is probably cheaper in the short term, but it is unlikely to deliver the full impact to realise the ambitious vision of the terms of reference of the UNFCITC. It may also increase burdens on businesses compared to a system that embodies DPI principles, such as parties only submitting information once. Irrespective of which approach is taken, decisions about financing and governance will have a significant influence. Balancing the broad need for understanding transnational beneficial ownership networks with the need for purpose limitation for access and use will also be a challenge.

This year has pointed to a reappraisal of multilateralism as the primary channel for international governance, leaving an open question on how any future mechanisms will be organised, as well as the likelihood for a single solution to be adopted globally. Perhaps multiple – but ideally complementary – initiatives may emerge, potentially at the regional or sub-regional level.

As part of its 2025-2030 strategy, Open Ownership is currently working on a policy briefing about centralising information to understand beneficial ownership networks, as well as conducting exploratory research to test assumptions around how better shareholder information and asset registration can improve transparency of these networks. Open Ownership will continue participating in the UNFCITC negotiations with these questions in mind.

Footnotes

[1] Although this should in theory be easier at the national level, many jurisdictions do not do this.

[2] In addition, the register would then contain the information it is requiring obliged entities to obtain, according to draft Regulatory Technical Standards. Obliged entities have to obtain “a reference to all the legal entities and/or legal arrangements functioning as intermediary connections between the customer and their beneficial owners, if any”. See: European Banking Authority (EBA), Consultation Paper – Proposed Regulatory Technical Standards in the context of the EBA’s response to the European Commission’s Call for advice on new AMLA mandates (EBA, 2025), https://www.eba.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2025-03/9bc83e61-e9a1-4e91-93de-2af8325e0182/Consultation%20Paper%20on%20Response%20to%20Call%20for%20Advice%20new%20AMLA%20mandates.pdf.

[3] Centralised shareholder registers also have the added potential benefits of helping protect shareholder rights and improve access to capital for private companies. See: Skatteetaten, Konseptvalgutredning Eierskapsopplysninger aksjer (Skatteetaten, 2024), https://www.skatteetaten.no/contentassets/b480645c1aec4e6f89c1226a57a70e76/2024-12-kvu-eierskapsopplysninger-aksjer-.pdf.

[4] There may still be additional interests that are relevant to collect beyond direct or indirect parties to a trust.

[5] For example, in deciding whether to prioritise mapping information collected to common categories, or retaining context-specific detail. See: Tim Davies and Peter Low, Describing interests: Research note (Open Ownership, 2025), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/describing-interests-research-note/.

Related articles and publications

Publication type

Emerging thinking

Blog post

Topics

Tax

Sections

Implementation,

Research

Open Ownership Principles

Central register