Solving the international information puzzle of beneficial ownership transparency

List of contents

- Introduction

- Why assets matter for beneficial ownership transparency of corporate vehicles

- Terminology

- Beneficial ownership of corporate vehicles vs. their underlying assets

- Stretching definitions

- Direct and indirect interests

- Interoperability

- Ways forward

Introduction

Open Ownership works towards better transparency in the beneficial ownership (BO) of corporate vehicles such as companies and trusts. In recent years, there has also been an increasing focus on the BO of assets. Assets are “[items] of property owned by a person or company, regarded as having value and available to meet debts, commitments, or legacies”. Whilst assets include company shares, this piece uses the term to refer to everything else, including tangible assets, such as land and real estate, jewellery, and yachts, and intangible assets, such as bank accounts.

The increased focus on the BO of assets is largely driven by efforts to reduce tax evasion and inequality, as well as tackling money laundering. For example, increased beneficial ownership transparency (BOT) of corporate vehicles through national registers and exchange of information by banks and tax authorities has been suggested to lead to an increase in wealth held in real estate investments, as recently presented by Jeanne Bomare at a symposium organised by Open Ownership and the London School of Economics in February 2024. Many policymakers and civil society organisations are setting their sights on the transparency of real estate ownership. A number of dedicated “beneficial ownership of assets” registers have been implemented globally, with most focusing on land and real estate.

Some go further, calling for a global asset register. This idea has emerged from the work of Thomas Piketty, Gabriel Zucman, and others to tackle global tax abuse and redress inequality, and it has been gaining some traction (notably, with a former European Union (EU) parliamentarian.) What a global asset register would look like has not yet been decided, but some suggest it would require combining national or regional asset registers, including information on the assets’ beneficial owners. Others have suggested “it requires creating a network interconnecting all national asset registries of all the different forms of wealth that an individual can own”, adding “the information deposited in the [global asset register] should come through interconnecting all national beneficial ownership registries in the world. This will require the creation of national beneficial ownership registries which will systematically gather beneficial ownership information across all asset types at the national level”.

The approach of national implementation and international aggregation requires interoperability, or the quality that different datasets possess whereby they work or communicate together without the need or use of additional tools or interfaces (as opposed to a supranational global register, like the International Maritime Organization’s Global Integrated Shipping Information System (GISIS)). Global asset register aside, interoperability is also critical for the usability of BO information for corporate vehicles more generally, in order to readily combine it with other BO (for example, to understand transnational corporate structures) and non-BO datasets (for example, sanctions lists). For BO information to be interoperable, it is important that it is not simply technically interoperable (for example, by using the same data standard), but also contextually interoperable. This means, to some degree, standardising the policy and legal frameworks around BOT as well, in order to consolidate and verify information, as explained eloquently by a legal specialist from Latvia’s BO register in this opinion piece.

Whilst a global asset register may seem a distant reality, the EU has already taken steps to join up its real estate registers. With the increased focus on the BO of assets, this piece will explore how this information interacts (or may interact) with BO information for corporate vehicles. This raises some critical questions on what the ideal global state of BO information could be, balancing idealism and pragmatism, and how to solve the international information puzzle.

Why assets matter for beneficial ownership transparency of corporate vehicles

Fundamentally, BOT of corporate vehicles is about how and where (economic) power is held and transferred within society in order to hold it to account. Assets are inherently relevant to the BOT of corporate vehicles as well as to the same policy drivers behind these reforms: assets are taxable; they can be used to launder money; and they can be sanctioned. Companies own assets, and company shares themselves are assets, as more complicated financial securities are based on them, such as derivatives. In addition, some legal definitions of the BO of corporate vehicles are tied to the company’s assets themselves, particularly where these focus on deriving economic benefit or the enjoyment of the company’s assets. See, for example, this excerpt from Ghana’s 2023 Company Regulations:

Trusts and other legal arrangements are structured around the assets held in trust. Put simply: without assets, there is no trust. Therefore, working towards the BO of assets may seem like a logical next step.

However, there are some key differences between the BO of a corporate vehicle and the BO of an underlying asset, both from an information perspective (who knows what, who is disclosing what), and when thinking about how to structure this information as data. Central to Open Ownership’s work on interoperability is the development of the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS). Currently in v0.4, its development captures our latest thinking on how best to structure information about individuals, corporate vehicles, and the relationships between them as data, so it can be readily and effectively combined and used.

The BO of corporate vehicles and assets appear to often be conflated in the discourse, yet the distinction is critical, as detailed in a new Open Ownership policy briefing on using BO information for fisheries governance. Conflation of the two may inadvertently undermine the goal of interoperable BO data from an information perspective, as this piece will explore.

Terminology

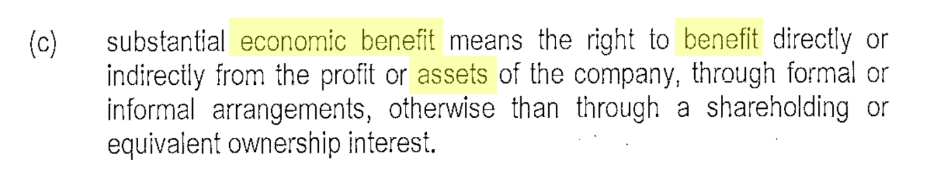

For the purpose of this piece, we will borrow terminology from both graph databases and BODS. We will talk about nodes to mean individuals, corporate vehicles, and assets, and the relationships between them. BO information comprises information about nodes (individuals and companies) and relationships between them (direct or indirect ownership or control). In the BO of corporate vehicles, the corporate vehicle is the declaration subject and the individuals are the interested party.

As we will explore, the relationships between nodes can be direct or indirect, but the more information we have about direct relationships, the more we can build up comprehensive pictures of a BO network by combining information. Part of the work at Open Ownership is thinking about what effective implementation looks like, and developing BODS involves understanding what these relationships – or interests – are in order to enumerate these in law and capture these in a structured way through forms.

Figure 1. Terminology

The circles in this diagram are nodes, and the lines are relationships, or interests. These can be direct or indirect.

Beneficial ownership of corporate vehicles vs. their underlying assets

This section will explain the difference between the BO of a corporate vehicle and the BO of an underlying asset, and why this may matter through two similar policy initiatives focusing on the BO of land.

British Columbia, Canada: Land Owner Transparency Register

In 2019, the Canadian province of British Columbia (BC) passed the Land Owner Transparency Act (LOTA) and created the Land Ownership Transparency Register (LOTR), following a report from the Expert Panel on Money Laundering in BC Real Estate. “The Land Owner Transparency Registry is a publicly searchable registry of information about beneficial ownership of land in British Columbia. Beneficial land owners are people who own or control land indirectly, such as through a corporation, partnership or trust”. Individuals are considered beneficial owners of the land if they have an “interest in land”, as defined in section 1 of LOTA, such as “an estate in fee simple; a life estate in land; a right to occupy land under a lease that has a term of more than 10 years, or a right under an agreement for sale to occupy land, or require the transfer of an estate in fee simple”. The asset (land, in this case), is the declaration subject. The register collects information about interested parties: individuals who have an indirect interest in the asset in question.

United Kingdom: Register of Overseas Entities

In early 2022, the Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) (ECTE) act received royal assent following an expedited passage through parliament in the United Kingdom (UK) (despite the bill already having been drafted in 2018) following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. The ECTE created the UK’s Register of Overseas Entities (ROE) owning UK property. The measure was widely reported on to mean that “foreign owners of UK property must declare and verify their identities” and “to stop overseas criminals and oligarchs from using agents to create companies or buy property for them in the UK”. However, a closer read of the ECTE revealed it did not, in fact, do this.

The ROE focuses on the beneficial owners of overseas corporate vehicles (legal entities and arrangements) that own UK land, meaning: the beneficial owners of the corporate vehicles who are legal owners of the asset, rather than the beneficial owners of the asset itself (as in BC). The declaration subject here is the corporate vehicle, and interested parties are individuals who hold interests in that corporate vehicle, rather than the asset. The interest in the asset is predefined as being a direct interest (i.e. legal ownership) of the asset by a corporate vehicle, captured on the Land Registry, in which a beneficial owner can have a direct or indirect interest.

The legislation defines beneficial owners of these overseas entities much like the definition of the register of beneficial owners of domestic corporate vehicles, focusing on (share) ownership and control over the corporate vehicle. (Confusingly, the definition also includes companies if they are subject to their own disclosure requirements.)

The Land Owner Transparency Register vs. the Register of Overseas Entities

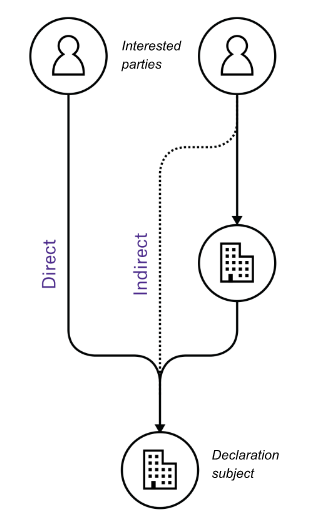

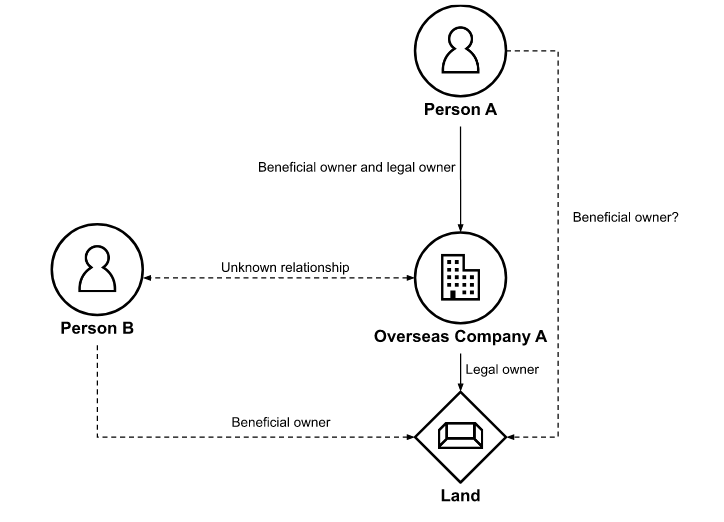

Despite the two BO disclosure regimes focusing on land, their scope is very different. The following diagram illustrates this:

Figure 2. Diagram showing the difference in scope between the Land Ownership Transparency Register and the Register of Overseas Entities

In this example, both the UK’s ROE and BC’s LOTR would collect information on Overseas Company A as a registered legal owner, including its beneficial owner, Person A. Only the LOTR would capture information on Person B, which has an indirect interest in the land through a lease agreement with Company B, making Person B a beneficial owner of the land under BC legislation. By contrast, the ROE would only capture information about the beneficial owners (as per UK legislation) of the legal owner of the land, where this legal owner is an overseas company. Source: Using beneficial ownership information in fisheries governance.

As mentioned earlier, understanding transnational BO networks (of corporate vehicles or assets) requires information from different sources to be combined. In this process, we may need to resolve data conflicts, for example, where information about the relationship between two nodes has been collected in more than one place. To do this, it helps if the information is interoperable and contains reliable identifiers. To start exploring the question of the BO of assets from an interoperability and informational perspective, the following section looks at a third initiative.

Scotland: Register of Controlled Interests

In 2022, Scotland launched its Register of persons holding a controlled interest in land (Register of Controlled Interests, or RCI). It has similar aims to the BC register. The asset (land) is the declaration subject.

As the Scottish government states: “This public register provides key information about those who ultimately make decisions about the management or use of land, even if they are not necessarily registered as the owner, including overseas entities and trusts”. But how it defines this is quite different to the LOTR: “The RCI is a register of persons who own, or are tenants of (under a long lease of more than 20 years), land, including entities with legal personality [known as recorded persons]. Entries flow from the recorded person, who is obliged to disclose persons who have significant influence or control over decisions in relation to land, known as associates”.

So whilst the Scottish register is similar to the BC register in that the declaration subject is the asset, the information it is collecting about interested parties and relationships is considerably different. The most obvious point here is the lease lengths: where Scotland focuses on leases of more than 20 years, BC focuses on 10 years or more, and the BC register may not include those who have significant influence or control in relation to the land.

What constitutes BO of an asset will be determined by laws of the jurisdiction that cover that asset (i.e. land and property law), just like how the BO of corporate vehicles is determined by the laws that govern those corporate vehicles. It is a reasonable assumption that there is more global divergence in legislation governing assets such as land and property than there is governing companies, which has already seen considerable standardisation in many jurisdictions (for example, the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA)). If this assumption holds, the standardisation challenges will be even larger for assets than those faced by the BO of corporate vehicles, meaning the knock-on barriers to comparability and use will also be larger.

The LOTR and the RCI highlight some key definitional differences, and differences in definitions are a key barrier to interoperability. To explore this further, the next section will look at legal definitions of BO of corporate vehicles and how these relate to assets.

Stretching definitions

During the passage of the ECTE, many parties identified ways for an individual to be able to evade disclosure but still own a property in practice. For example, if an individual would ask a corporate service provider (CSP) – a company – to buy a property on their behalf through a nominee agreement, this individual could use the property and have effective control over it without being a beneficial owner of the CSP owning the land itself, meaning it would therefore evade disclosure despite being a beneficial owner of the land. Various efforts aimed to extend the mandate of the ROE from transparency over the beneficial owners of foreign companies that are registered legal owners of land to beneficial owners of the land itself. When the ECTE went through the UK legislature’s upper chamber, three members tabled an amendment (which was voted down) “to require overseas entities to disclose the beneficial owners of UK property which they hold, even where the beneficial owners of the property are not beneficial owners of the entity”. They proposed to add the following to the definition:

Any individual [...] is a “registrable beneficial owner” in relation to an overseas entity if they are a beneficial owner of a qualifying estate (as defined in Schedule 4A to the Land Registration Act 2002) or of a share in such an estate that is held by the overseas entity, whether or not the individual [...] itself holds any interest in that overseas entity.

In other words, any individual that is a beneficial owner of the land of which a company is registered as the legal owner is also a beneficial owner of the company. Whilst this would include the individual in Figure 2 above, adding these types of clauses arguably stretches the definition of BO for corporate vehicles to something that becomes very ambiguous, as it tries to capture certain interests individuals hold in an underlying asset under the definition of the BO of the corporate vehicle. It makes both the asset and the corporate vehicle the subject of disclosure, risking confusion (and therefore opacity) of the interests: the relationships between the individuals, the corporate vehicle, and the asset. Specifically, it becomes very challenging to know what relationship the individual has to the company, and whether this is direct or indirect, particularly when trying to capture this as structured information.

Figure 3. Diagram showing the implications of the proposed amendment to the Register of Overseas Entities

Person B would have been captured in the proposed amendment to the ROE.

Continuing with the example, one would need to collect some information about what relationship the individual has to the CSP in order to start making sense of it all, especially if the intention is to connect the information to see full BO networks. This is explored in greater detail further on in this piece.

“Benefit” in beneficial ownership definitions for corporate vehicles

The tendency to stretch definitions to cover information about assets is currently most relevant in discussions about whether to include the concept of “benefitting from” in the definition of the BO of corporate vehicles. Many do advocate for this, for example arguing that the part of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) definition “on whose behalf a transaction is conducted” comprises those who benefit from a corporate vehicle. Open Ownership argues that historically in most company law, control and benefit were closely tied to ownership (share ownership meant voting rights and dividends). However, as control was increasingly decoupled from ownership (“morphable ownership”), BO definitions explicitly started covering these different prongs. “Benefit” can also be decoupled from both control and ownership (for example, through a trust, the right to enjoy a company’s assets, or stock lending), although not all legal definitions of BO of corporate vehicles account for this. Ghana, the example mentioned earlier on, does include this (see above).

To illustrate a simple use case for including the concept of “deriving benefit from” in the BO of corporate vehicles, imagine a country that is implementing BOT of corporate vehicles to combat corruption. In this example, a corrupt politician has swayed a procurement decision in favour of Company A that has promised a bribe. In some known cases, the corrupt politician may receive the bribe in the form of the corrupt Company A giving bogus, high-fee consultancy contracts to the politician’s Company B. Whilst BOT of corporate vehicles following definitions focusing on ownership and control reveals the politician owns Company B, this would not reveal that the politician is benefitting substantially from Company A. (For a real-world example, see Box 3.2.) Another example could be where a corrupt politician would acquire usufruct rights over a company’s assets without ownership (for example, being able to live in a mansion, use a yacht), or a right to income of those assets. In fact, some legal definitions of the BO of corporate vehicles explicitly include the concept of enjoyment of assets.

Whilst this use case for stretching a BO definition for corporate vehicles to include benefit is clear, it is equally clear that collecting information on all individuals that benefit from a company (for example, an individual being paid a salary for normal employment) would not be desirable, and it seems evident that some parameters should be set. As once mentioned by a bank representative in a discussion about thresholds: “if everyone is a beneficial owner, nobody is a beneficial owner”. Whilst this is a slightly separate discussion, the concept of “benefitting from” closely relates to assets, and Open Ownership will be doing more work on this in the coming year.

This may become a very slippery slope, as BO definitions for corporate vehicles may start to capture endless interest types relating to their underlying assets. As demonstrated above, this may result in the collection of information about indirect relationships involving individuals, companies, and assets, potentially obscuring specific relationships between them. The next section will explore some challenges around indirect interests for connecting different information sources to understand BO networks.

Direct and indirect interests

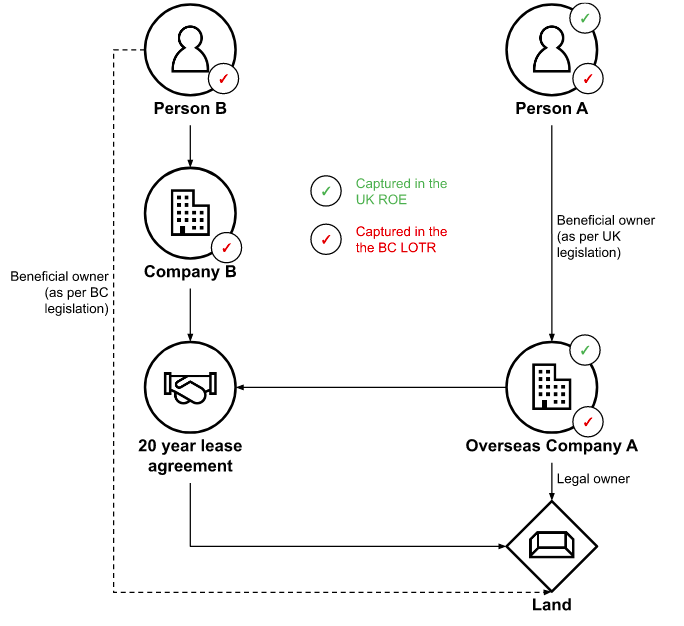

When definitions of BO are stretched to include many different indirect interest types (see, for example, the amendments to the ROE above), the resulting BO declarations can end up overlapping and capturing information on certain nodes and relationships more than once. This is already the case with the BO of corporate vehicles. A company will declare the same indirect BO relationship with a 100% ownership interest as its parent company.

Figure 4. Diagram showing how declarations about indirect interests capture information about the same individuals and corporate vehicles

Both Company A and Company B will declare information about Person A in BO disclosures. Depending on the specific information captured, Company A may also provide information about Company B.

In this example, duplicate information may be easily reconcilable, but it will be more challenging to piece together a more complicated structure from multiple sources capturing indirect relationships, especially where these also involve assets. The relationships between individuals, corporate vehicles, and assets can become less clear, as in the example of the ROE amendment above. Perfect information should not be the enemy of the good, but knowing an individual has some link to a node may not be hugely helpful if the number of individuals being captured also exponentially increases.

From an information perspective, this can be both challenging as well as inefficient. In practical terms, when people make declarations about indirect interests covering a range of individuals, corporate vehicles, and assets, it becomes incredibly laborious and potentially impossible to connect and combine the information to form a complete picture. For example, if anyone who is a beneficial owner of a company would also be considered the beneficial owner of its underlying assets, then disclosure systems where the asset is the declaration subject may collect the same information as declaration systems where the company is the declaration subject. This can introduce information redundancy and may lead to data conflicts which can be costly or impossible to resolve. In other words, the data becomes less interoperable.

The idea of interconnected BO information being a perfect reflection of reality is neither desirable nor achievable. To illustrate, many financial investigators use BO information to set the parameters of an investigation. For these users, knowing a person has some link to an asset may be preferable to no information at all. However, for many of the use cases, and for verifying the information for accuracy, being able to know what conclusions can be drawn from comparing two inconsistent records is equally important. Not being able to do this may also mean certain interests remain undisclosed as they remain easily hideable.

There are also other considerations. Requiring the disclosure of many overlapping indirect relationships will also lead to a higher compliance burden, as declarants are expected to report on information outside their immediate sphere of knowledge, and any change in this sphere may require a new declaration. This information may also be provided to one register or authority about nodes that are overseen by other authorities, which may pose challenges to verification. It therefore may make sense to increase the directness of the scope of information collected, and to increase the reliance on interoperability to join up information for complete pictures of ownership structures.

To illustrate this point: comprehensive and interoperable information about direct interests in a company (shareholders, voting rights) and direct relationships between those direct interests and other parties (for example, a nominator in a nominee relationship) would give a far better and more reliable picture of a BO network than what is available in most current BO disclosure regimes. The concept of BO has developed in part to tackle a lack of (usable and accessible) information on direct interests, especially when crossing borders, so the concept of BO to capture indirect interests will remain useful. It is also worth exploring how BO disclosure systems can best use or collect information on direct interests. (Some BO registers for corporate vehicles already use shareholder information to conduct the FATF’s “verification of status” requirement, although this information is not available to the same extent and quality in all jurisdictions.)

Collecting this information as part of BO declarations is also not necessarily straightforward. The more information that is collected about direct relationships between nodes as part of information about indirect BO relationships (i.e. intermediaries in an indirect BO relationship), the more different declarations made to a register will overlap, and therefore create information redundancy. For example, if all declaration subjects were required to disclose full ownership chains with all intermediaries, many declarations would cover the same intermediary companies and their relationships. Adding to this that reporting obligations allow for this information to be declared at different times, it may make piecing this information together, or verifying anything if there are data conflicts, very challenging.

As mentioned, it is more reasonable to expect declaration subjects to have (accurate) knowledge of direct interests than potentially distant indirect interests, so it can be assumed that such conflicts will arise. In Greece, information on ownership chains “is retrieved automatically” rather than collected, and entries are automatically connected when all companies in the ownership chain are incorporated domestically, lowering the compliance burden and improving accuracy. Open Ownership is currently developing guidance on how best to approach this.

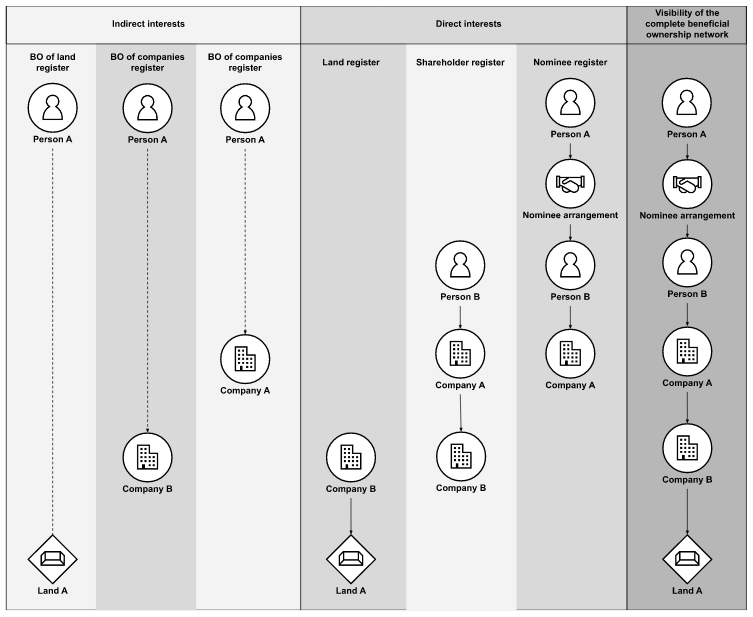

Figure 5. Diagram showing how information about indirect and direct relationships can contribute to visibility over complete beneficial ownership networks

In this example, the easiest and most reliable way to have visibility over a complete ownership network (here, complete information about the indirect relation between Person A and Land A, including all intermediaries) is to combine sources of information about direct interest (solid lines). Sources of information about indirect interests (dotted lines) can obscure intermediary nodes and relationships – for example, the role of Person B (nominee), and the relationship between Company A and Company B.

Interoperability

As mentioned earlier, improving interoperability requires – to some degree – standardising the policy and legal frameworks around BOT. For example, information collected in the LOTR or the RCI would not be very contextually interoperable with a domestic BO register for corporate vehicles because the interest types captured by the definition of BO are fundamentally different. Moreover, the data collected in the LOTR and the RCI may not include extensive information on direct interests; rather, it primarily focuses on the relationships between individuals and assets. Even though in some cases a corporate vehicle may play a role in these relationships, it does not collect extensive information on those nodes and relationships. In contrast, for corporate vehicles, the world has been incrementally moving towards standardising some of these aspects as international standards slowly converge. Information collected in the ROE is more contextually interoperable with information from the UK’s domestic BO register for corporate vehicles because there is some degree of standardisation in the interest types being collected. (This, arguably, leads to a more comprehensive view of corporate networks, but it may not provide information about specific interests in the asset, as flagged in the proposed ROE amendment.)

A drive to implement asset-specific BO registers may lead to a proliferation of different definitions of the BO of various assets globally and even larger challenges with standardisation than those that exist for corporate vehicles. Domestically, it may lead to different government departments setting up their own efforts to define and collect BO information. This can already be seen in extractives and procurement. Whilst this may be a pragmatic way forward in the absence of having high-quality, centralised BO information for corporate vehicles accessible across government, it does lead to increased regulatory burden, ambiguity, and redundancy. None of these efforts would be capitalising on centralised and cross-governmental approaches to verification of BO registers for corporate vehicles, which governments are implementing in response to obligations by various international anti-money laundering standards. A likely outcome of this scenario would lead to an increase in the amount of information about indirect relationships between individuals and assets, which may not include information about many relevant parties and direct interests.

Ways forward

Combining information on direct interests relies heavily on interoperability and having reliable identifiers to combine information from multiple sources. The information needs to be available and combinable, including across borders. The world is far off from that being a reality. Therefore, information on – and the concept of – the BO of corporate vehicles will continue to be incredibly useful. However, with the increasing focus on assets and asset registers, policymakers should be thinking more broadly about the information ecosystem they want to be working towards. A proliferation of various BO asset registers in specific jurisdictions may produce useful information, but it may also create regulatory burden, ambiguity, and make the data less interoperable. Standardisation of definitions of the BO of assets (a potential precondition to a global BO of assets register) seems to be a long way off, and centralising this information internationally (for example, in a global asset register) would be a big challenge.

In the short term, it may be more productive to continue to focus and leverage the progress made on the BO of corporate vehicles; ensure this is readily combinable with other sources of information about assets; and improve the quality (and the accessibility) of these sources. In addition to collecting information on direct interests, it is critical for asset registers to collect and share reliable identifiers for corporate vehicles where they have an interest in the asset, in order for this information to be readily integrated. This would potentially be less comprehensive (as not all indirect interests in an asset would be covered), but it would leverage all ongoing efforts. It also has the promise of interoperability: being able to combine information on the BO of corporate vehicles from multiple jurisdictions for transnational investigations and due diligence; linking these to assets; and better understanding how these link to the assets. To be more comprehensive, asset registers could potentially start to collect information on additional direct interest types as well as registered legal ownership.

In the long term, the types of interests that interested parties can have in corporate vehicles should be standardised from an information point of view, technically (as the development BODS seeks to achieve) and contextually. These interests ultimately boil down to a range of rights broadly afforded by the concept of “ownership” in law. Where these can be sufficiently abstracted, simplified, and generalised, this may allow these information models to be scaled beyond corporate vehicles in the future to potentially also cover assets, and they may lay down a necessary foundation for something like a global asset register.

Current and prospective users of this information are the right people to help inform the best way forward, and this piece may help start this conversation. What specific use cases are enabled by the collection of information on specific interests with respect to assets, and to which policy areas does this contribute? Is more information preferable to better-connected information, even in the long run? What information would potentially be missing if we focused on the BO of corporate vehicles, and integrated that information with asset registers? What information is lost or gained with focusing on interoperability? Diligent user research may help policy makers answer some of these questions. What is clear from the research done to date is that the lack of standardisation and interoperability are significant barriers to data use and usability. Therefore, Open Ownership has been focusing on getting the BO of corporate vehicles right, and on providing legislative and technical solutions to the informational puzzle of interoperable BOI.

If you have any questions or thoughts on this piece, please email the Policy and Research Team at Open Ownership: [email protected].

Author:

Contributors:

Kadie Armstrong, Miranda Evans, Alanna Markle

Reviewers:

Publication type

Emerging thinking

Blog post

Topics

Beneficial Ownership Data Standard

Sections

Implementation

Open Ownership Principles

Structured data