Beneficial ownership transparency and the United Nations Convention against Corruption: progress and recommendations

Looking forward: using beneficial ownership data to prevent and detect corruption

The follow-up process to the UNGASS political declaration marks a critical opportunity for States parties to better prevent, detect, and combat systemic corruption. More specifically, BOT can drastically reduce corruption risks through informed decision-making among all relevant stakeholders – government actors, journalists, civil society, and the private sector.

There are untapped opportunities to prevent and detect corruption by unlocking company ownership information for all these stakeholders by challenging those seeking to abuse their positions for personal gain. In instances of political or grand corruption, BO information is being used across jurisdictions to investigate corruption and follow the money, reduce corruption risks through informed decision-making, and support data analysis that is contributing to novel anti-corruption insights, and hence real-life impacts.

Law enforcement, civil society, governments and others across various countries have been using BO data and analysing it to better understand patterns and behaviours that may point to corrupt practices. Such analysis can offer new insights into how corrupt actors navigate and exploit financial and economic systems, and therefore trigger proactive investigations. The full potential of BO data is still untapped, and significant potential exists to integrate it with other datasets to inform anti-corruption policy-making and uncover systemic risks.

The full potential of BOT in combating corruption globally similarly depends upon who has access to the data and how it is structured (see later section: Structured data matters).

Combating corruption with broad access to beneficial ownership data

For optimal results, reforms must prioritise access to information [13] for all anti-corruption actors, while also setting up adequate measures to protect the data and privacy [14] of those making disclosures. Making a subset of information in BO registers available beyond governments and banks is an efficient way of doing this.

Over 120 countries have already committed to central BO registers for companies, and the majority of these have committed to making information public for companies in at least one sector of their economy. Other countries are implementing regimes that allow access for users who can demonstrate a legitimate right to access the information. However, legitimate interest access regimes which have been implemented to date are seemingly less effective in addressing corruption, as this approach can have a chilling effect on the use of the data for anti-corruption purposes. Such regimes appear to increase the time and cost of accessing BO information, and may restrict the amount and format of data available to users, in ways that inhibit its interoperability and therefore limit its use to prevent and detect corruption. [15]

Making a subset of information in a BO register publicly accessible is the most efficient way to ensure all anti-corruption actors can play their part in using the data to prevent and detect corruption. Evidence shows that making BO data public delivers anti-corruption benefits not just for civil society and journalists, but also for governments, law enforcement authorities, and the private sector.

Government users: benefits of public beneficial ownership information

Public beneficial ownership information has been shown to significantly improve the speed and ease of access for existing public sector users, such as for non-domestic law enforcement and financial intelligence units for whom investigations involving transnational corporate structures tend to be difficult and require significant time and resources. [16] In fact, before the implementation of the UK BO register, up to half of the investigation time in complex corruption cases involving anonymously-owned companies was spent piecing together BO information. [17] Following the introduction of the UK’s beneficial ownership register in 2016, a statutory review found that UK law enforcement agencies used the register regularly, viewing it as positive for their work due to making it quicker and easier to obtain beneficial ownership information for UK companies. [18]

Given the tendency for illicit financial flows to be moved across borders, it is imperative that BO information is accessible to appropriate foreign law enforcement actors. Investigators have used public BO information to successfully track unexplained wealth – assets belonging to people in positions of power and influence that do not align with their official salaries or declared revenues and assets.

UK beneficial ownership data reveal links to Azerbaijan

Beneficial ownership information from the UK’s register was used to help reveal the real estate and business empires of two children of Azerbaijan’s Minister of National Security between 2003 and 2015. [19] The family was found to have jointly held and owned more than €100 million worth of companies and properties. While the origins of the wealth were never properly justified, the Minister’s official salary of not more than €1,500 per month certainly could not explain the family’s level of wealth. The UK beneficial ownership register was crucial to shining a light on the family’s suspicious deals and helped create a case for law enforcement authorities.

Using beneficial ownership transparency to combat corruption in public procurement

The use of BO information during public procurement is exceptionally important. Knowing who owns companies that will provide goods and services to governments, and who ultimately benefits from public contracts, is crucial for effective oversight of public spending. This increases the likelihood of quality service delivery, helps ensure well-managed risk, value for money and increases trust in government. [20] In some cases it is also a matter of national security.

The 2021 UNGASS political declaration recognises the importance of combating corruption in public procurement). [21] This is now also recognised in the FATF Recommendations. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimates that countries spend an average of 13% to 20% of their gross domestic products on procurement, while 57% of all foreign bribery cases are due to procurement corruption. The impacts are significant as the global value of public procurement is estimated at $13 trillion. In this context, BOT is a crucial anti-corruption tool, facilitating the detection of undisclosed or hidden conflicts of interest and identifying red flags for collusion and bid-rigging.

While several countries have made progress to implement BOT within procurement, or use beneficial ownership data in procurement processes, there is a widespread need for greater focus on making full use of BO data to inform procurement decisions. In addition to amending policies and practices, ensuring beneficial ownership and contracting data are available in structured formats can greatly increase the scope to analyse it to inform procurement decisions.

The importance of beneficial ownership data to protecting national security in public procurement

A US Government Accountability Office (GAO) review found that, as of March 2016, the US Government had been leasing high-security space from foreign owners in 20 buildings. This included space for six Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) field offices and three Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) field offices.

The spaces were used, among other reasons, for classified operations and to store law enforcement evidence and sensitive data. The companies owning the spaces were based in countries such as Canada, China, Israel, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. The GAO was unable to identify ownership information for about one-third of all 1,406 high-security leases, because ownership information was not available for all buildings. National security risks in these cases include espionage, cyber intrusions, and money-laundering. [22]

Private sector users: benefits of accessing beneficial ownership information

BO information can be of significant value to actors in the private sector, both those in the anti-money laundering regulated sectors (such as financial institutions, lawyers, accountants, etc.) and businesses small and large operating in all sectors of the economy. Some of the most important benefits for these users include stronger risk management, better informed investment decisions, simpler compliance with government regulations, as well as improved environmental and social governance.

BO data is being used to reduce compliance costs related to anti-corruption and money-laundering regulations. Access to BO information held in central registries provides stakeholders in the private sector with additional channels of information to conduct robust due diligence processes among supply chains and business partners – an area of risk increasingly relevant in today’s globalised economy. In fact, the current opacity in ownership of corporate vehicles globally is creating systemic risk, as well as other financial and non-financial risks (e.g., legal, reputational, political, operational, and regulatory risks). [23]

More specifically, to make sound and responsible investment decisions, investors need to know who they are dealing with and what the track record is of those with whom they do business. This is an important way for shareholders to protect themselves against fraud, losses, or unknown dealings with PEPs who may be engaging in nefarious business activities. With access to this information, investors can better conduct the necessary due diligence to protect the long-term value of their holdings, manage all types of risk, and ensure their own responsible business conduct.

Broader access to BO data can help level the playing field between corporate actors, which also contributes to greater trust in the integrity of a business environment. This data may help prevent corrupt companies from benefiting from unfair advantages, or help detect and also prevent other business-related criminal and corrupt activity, such as counterfeiting, trademark infringements, theft of intellectual property or procurement fraud.

Finally, business actors having access to BO information facilitates economic activity around data re-use. This generates economic value for the economy, and adds value to the ownership information itself, facilitating its use in innovative ways for the benefit of society.

Case study: The Clearing House Association

The oldest banking association in the United States (US), The Clearing House Association, which advocates on behalf of the largest US commercial banks, such as Bank of America, Wells Fargo, and SunTrust, has supported the push for greater transparency about the real owners of US companies. According to The Clearing House, allowing financial institutions access to this information would better enable banks to comply with the US regulations requiring them to find out who are the beneficial owners of their corporate clients. [24]

Case study: Cobalt International Energy

Texas-based Cobalt International Energy formed joint ventures in Angola in 2010 with two anonymously-owned companies. One was later revealed to be owned by three senior, powerful Angolan officials who held considerable undisclosed interests in the impoverished country’s oil sector. As a result, Cobalt was investigated for potential breaches of the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and US Department of Justice (DOJ). The SEC dropped its case in 2015, while the DOJ’s investigation continued until 2017. Cobalt denied any misconduct or knowledge of the secret involvement of Angolan officials in the oil deal; nonetheless, it experienced an 11% drop in its share price after revealing news about the investigation and its quarterly losses to its investors in August 2014. [25]

Civil society and media users: benefits of access to beneficial ownership information

Civil society and the media actors play a critical role in global anti-corruption efforts. Their research and investigations into financial crime and corruption, as well as their campaigning make an important part of the journey to bring major cases to the attention of both authorities and the wider public. For example, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) has contributed to over USD 7.3 billion in fines being levied and assets being seized, and over 500 arrests, indictments, and sentences. [26] The use of BO information by NGOs and investigative journalists, is a critical tool in such investigation, and, combined with other types of data, helps detect the misuse of legal entities.

Given the risks that journalists in many contexts face when investigating corruption and large-scale financial crimes, journalist networks have highlighted the importance specifically of accessing BO information without registration requirements or tracking of their usage of registers, and without barriers such as payments or providing justification of their need to access information. [27] Therefore journalists, along with civil society organisations who can face similar risks, are key supporters of public BO registers.

Providing civil society with access to BO data facilitates meaningful oversight, and provides opportunities to hold governments to account, as well as opportunities to verify the data by using it in practice. This broad access to company ownership information increases the risks of undertaking corruption, making it harder for criminals and the corrupt to move stolen money, exploit conflicts of interest, or engage in high-level corruption without their activities being seen.

Media and civil investigations using beneficial ownership information

The release of the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers in 2016 and 2017 showed the crucial role of international collaboration among journalists to address the use of anonymously owned companies for concealing beneficial ownership by uncovering many alleged cases of grand corruption. The value of public beneficial ownership data was further illustrated by the OpenLux investigation led by Le Monde and the OCCRP. Many examples exist to show how access to beneficial ownership for media actors is a critical element to successful investigations. [28]

The independent media and anti-corruption investigation organisation Bihus.info investigated a Ukrainian Member of Parliament (MP). It combined data from Ukraine’s asset and BO registers to examine the source of UAH 1.2 million (approximately USD 42,000) in annual rental income declared by the MP. They found that the source of the reported income was likely from proceeds of corruption. The High Anti-Corruption Court of Ukraine also investigated this case. In 2021 it ruled that the income was illegitimately acquired and should be subject to civil forfeiture – the first time this mechanism had been used since it was introduced in 2019.

Using the Ghanaian national BO register, NORPRA, a Ghanaian civil society organisation, found that shareholders and directors of an Australian company operating in Ghana had been sanctioned and sentenced to prison terms in the past. The Companies Act 1963 prohibits persons with criminal records, convictions or fraudulent acts from running companies in Ghana. The company had obtained a mining licence before the Act was passed in Ghana. When the organisation NORPRA discovered these facts, it alerted the authorities, who then verified the data and revoked the permit granted in 2020. NORPRA researched and obtained the beneficial ownership information by accessing (for a fee) the Ghana Companies Registry, as well as consulting court cases made public via Australian online sites.

Balancing transparency with privacy and data protection

Following the judgement [29] of the CJEU in November 2022, the question of how to balance privacy with access to BO data has gained further urgency and prominence. Change is already underway in some countries that currently provide public access to BO registers to safeguard privacy, and balance this with public access to achieve anti-corruption benefits. Examples of the changes some countries are undertaking include:

- information collected may be limited to what is strictly necessary (data minimisation);

- a smaller subset of information may be made available to the public than to domestic authorities;

- sensitive data fields that are unnecessary to generating benefits may be omitted (layered access); and,

- protection regimes may include exemptions to publication in circumstances where someone is exposed to disproportionate risk.

These measures are also applicable in countries where access is granted based on legitimate interest, as part of an overall legal and operational framework to balance transparency with privacy.

In these types of frameworks, the broad public interest in disclosures of the information should be clearly defined in law. Judgements in the CJEU have highlighted that the narrow focus on using BO information to tackle money-laundering in the EU 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive ignores the broader application of this information to various issues of public interest.

Countries such as the UK and some within the EU have justified public access to BO information as necessary and proportionate to achieve much broader policy goals, such as supporting a transparent business environment. Using a broader policy justification enables policy and judicial actors to take a more accurate range of benefits from public access to data into account when evaluating whether privacy is appropriately balanced with transparency. [30]

In practice, public access to BO information is currently the most efficient way to enable data users to access the information they need to help tackle corruption. [31] However, where that is not possible, legitimate interest regimes may be useful to grant access to a range of anti-corruption actors, and should be implemented in ways that minimise barriers to using the data.

Structured data matters

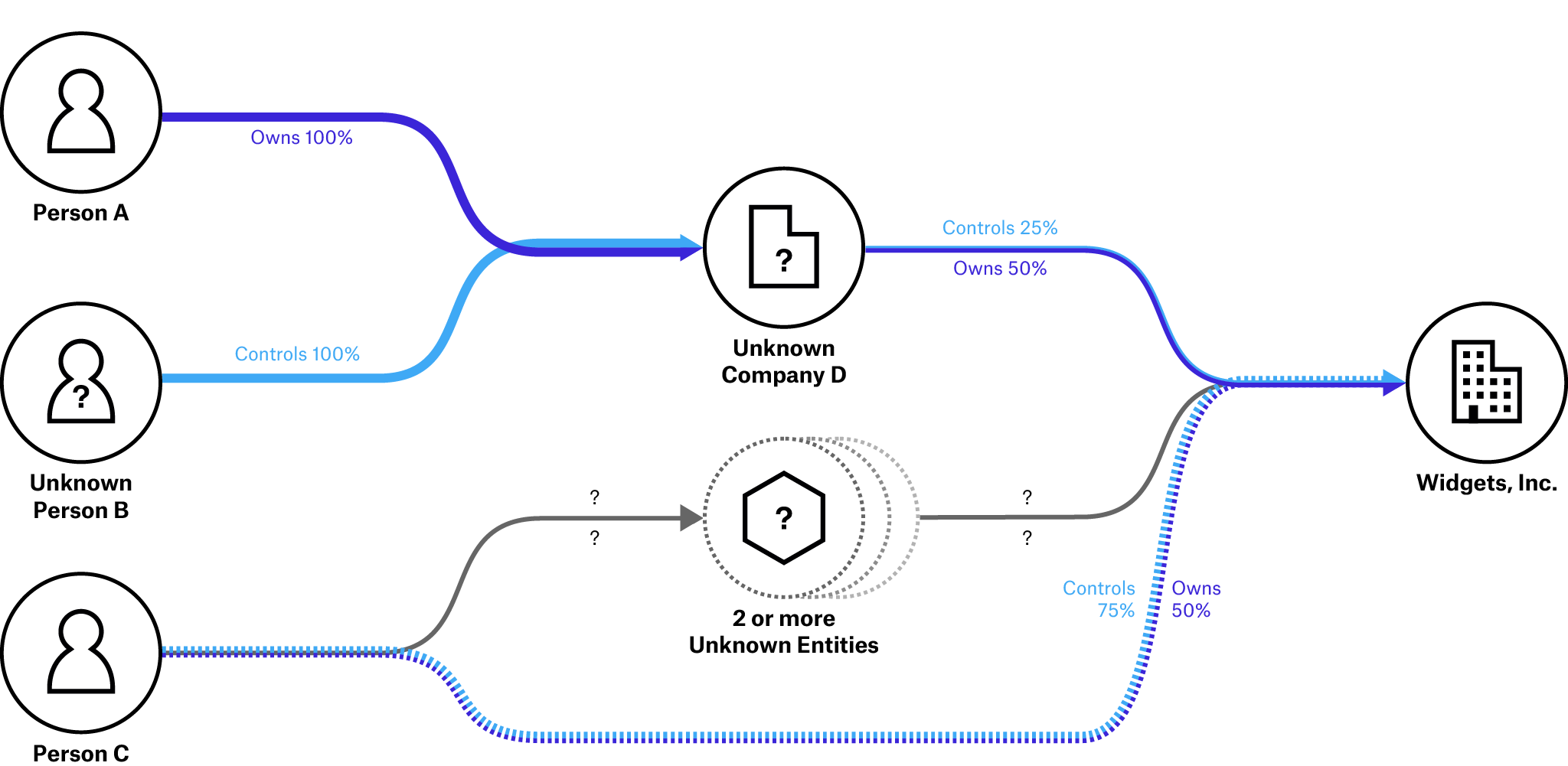

Grand corruption tends to involve transnational money flows and therefore calls for cross-border investigations. To do this effectively, BO data must not only be available in different countries, but must be interoperable so it can be linked and analysed with other relevant datasets. This includes using appropriate identifiers for people and companies in the datasets, meaning for example that analysts can easily determine whether two people with the same name are actually the same person.

Adopting a common data standard such as Open Ownership’s Beneficial Ownership Data Standard will help to ensure that company ownership information is used to its maximum potential to combat corruption.

Moreover, making the information available as structured data allows for new types of analysis and processing that further enables all relevant stakeholders to use the data. This approach reduces the ongoing costs of producing, using, and maintaining the information, as structured data can be readily incorporated into existing processes which can be more easily automated.

The 2021 UNGASS political declaration acknowledges the role of technologies in implementing anti-corruption measures and the importance of strengthening cooperation and the exchange of best practices on the development and application of such technologies. [32] For example, when national registers provide structured and interoperable data, beneficial ownership data can be readily combined with other data, such as procurement data, or with beneficial ownership data from other national registers to improve visibility of transnational corporate structures. This is demonstrated by the Open Ownership Register, the world’s first publicly accessible transnational beneficial ownership register, currently combining data from four national registers.

The Beneficial Ownership Data Standard

Open Ownership, in collaboration with Open Data Services and other international experts on data standards, has developed the Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS) to serve as a framework for collecting and publishing BO data, enabling the resulting data to be interoperable, more easily verified, and used. A common data standard enables sharing of data between different users, both inside and outside of governments, and allows for a rapid build-up of best practice on collecting, storing, and publishing beneficial ownership data. A data standard also ensures the interoperability [33] of the data with other foreign data sets – for example, those covering public procurement, sanctions, and PEPs. Countries like Armenia, Latvia and Nigeria have been implementing BODS for their registers. Data from Denmark, Slovakia and the UK is also publicly accessible in BODS format through the Open Ownership Register.

Nigeria setting the standard in Africa

In May 2023 Nigeria became the first African country to publish BO data in line with Open Ownership’s Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (BODS). Using BODS means that agencies across its government can more easily access and use the data and combine it with other internal datasets and connect it with BO data from across the globe.

Government representatives expect this move to greatly enhance the fight against corruption and criminality by facilitating investigations, supporting civil society in promoting citizens’ participation in public accountability and governance, and strengthening the media’s capacity to act as a watchdog in the society. This marks a milestone in the Nigerian Government’s efforts to work with internal and external stakeholders to implement robust BOT reforms.

Open Ownership Register

The Open Ownership Register allows users to search structured data on over 8 million companies from more than 200 jurisdictions in one place, and Open Ownership provides supportive tools such as a data visualiser to help users identify and understand connections between individuals and companies.

Notes

[13] See the Open Ownership Principle “Access” for more detailed recommendations on best practice for making BO information accessible to diverse stakeholders, https://www.openownership.org/en/principles/access/.

[14] See recommendations and related resources in Open Ownership’s Statement on Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) judgement on public beneficial ownership registers in the EU (Open Ownership, 2022), https://www.openownership.org/en/news/statement-on-court-of-justice-of-the-european-union-cjeu-judgement-on-public-beneficial-ownership-registers-in-the-eu/.

[15] Maíra Martini, Maggie Murphy, G20, Leaders or Laggards (Transparency International, 2018, https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/2018_G20_Leaders_or_Laggards_EN.pdf.

[16] Tymon Kiepe, Open Ownership, Making central beneficial ownership registers public, (Open Ownership, 2021), www.openownership.org/en/publications/making-central-beneficial-ownership-registers-public/.

[17] Louise Russell-Prywata, Beneficial ownership and wealth taxation: An assessment of the availability and utility of beneficial ownership data on companies in the administration and enforcement of a UK wealth tax (Wealth Tax Commission, 2020), www.wealthandpolicy.com/wp/BP124_BeneficialOwnership.pdf.

[18] Louise Russell-Prywata, Beneficial ownership and wealth taxation, www.wealthandpolicy.com/wp/BP124_BeneficialOwnership.pdf.

[19] Chinwe Ekene Ezeigbo, Louise Russell-Prywata and Tymon Kiepe, Early impacts of public registers of beneficial ownership: United Kingdom (Open Ownership, 2021), www.openownership.org/en/publications/early-impacts-of-public-beneficial-ownership-registers-uk/.

[20] Eva Okunbor and Tymon Kiepe, Beneficial ownership data in procurement (Open Ownership, 2021), www.openownership.org/en/publications/beneficial-ownership-data-in-procurement/.

[21] Article 11, Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 2 June 2021 (United Nations General Assembly, 2021), page 5 https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N21/138/82/PDF/N2113882.pdf?OpenElement.

[22] Tymon Kiepe, Using beneficial ownership data for national security (Open Ownership, 2021), www.openownership.org/en/publications/using-beneficial-ownership-data-for-national-security/.

[23] Investigations and legal proceedings concerning alleged fraud and bribery facilitated by anonymously-owned companies pose serious financial risks for investors and associated businesses. The consequences could include legal fines and fees, protracted legal proceedings, long-term reputational damage resulting in lower revenues, and compliance or monitoring costs, all of which can negatively affect a company’s value.

[24] See also Julie Rialet, Mark Hays, What’s in it for business? The US case: Lessons from private sector and civil society advocacy for beneficial ownership transparency reforms (Open Ownership, 2023), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/whats-in-it-for-business-the-us-case/.

[25] Chancing it: How secret company ownership is a risk to investors (Global Financial Integrity and Global Witness, 2016), https://www.globalwitness.org/en/reports/chancing-it/.

[26] Nkirote Koome, OCCRP: Using investigative journalism and big data in the fight against corruption (Luminate, 2021), https://luminategroup.com/posts/news/occrp-using-investigative-journalism-and-big-data-in-the-fight-against-corruption.

[27] Alexandra Gillies, The EU Ruling on Ownership Transparency and What It Means for Journalists, (OCCRP, 2023), https://www.occrp.org/en/beneficial-ownership-data-is-critical-in-the-fight-against-corruption/faq-the-eu-ruling-on-ownership-transparency-and-what-it-means-for-journalists.

[28] Also see Alanna Markle and Tymon Kiepe, Who Benefits? How company ownership data is used to detect and prevent corruption (Open Ownership, 2022), https://www.openownership.org/en/publications/who-benefits-how-company-ownership-data-is-used-to-detect-and-prevent-corruption/ and Beneficial Ownership Data Is Critical In The Fight Against Corruption, (OCCRP, 2022), https://www.occrp.org/en/beneficial-ownership-data-is-critical-in-the-fight-against-corruption/.

[29] Court of Justice of the European Union, “Press release No 188/22, Anti-money-laundering directive”, 22 November 2022, https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2022-11/cp220188en.pdf.

[30] For more information see the Open Ownership principle "Access", https://www.openownership.org/en/principles/access/.

[31] Tymon Kiepe, Open Ownership, Making central beneficial ownership registers public (Open Ownership, 2021), www.openownership.org/en/publications/making-central-beneficial-ownership-registers-public/.

[32] Article 68, Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 2 June 2021 (United Nations General Assembly, 2021), page 15, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N21/138/82/PDF/N2113882.pdf?OpenElement.

[33] Interoperability means being able to readily use the data with other sources, and integrate it into different systems and processes. The transnational nature of complex BO relationships makes combining BO datasets from different jurisdictions essential to gaining full visibility of ownership structures.