Эцсийн өмчлөлийг хуульд хэрхэн тодорхойлох: Тодорхойлолт ба босго

Thresholds

For the most common forms of ownership and control – namely, direct or indirect possession of ownership shares, voting rights, and right to income – most jurisdictions establish a threshold for disclosure requirements, expressed as a percentage of total ownership or control. Determining the level at which to set these thresholds is often a central area of debate when countries draw up legal definitions of BO. As a general principle, low thresholds are important to ensure that most or all people with relevant BO and control interests are identified in the disclosures. However, there is no one-size-fits-all level for thresholds since different percentages will be appropriate in line with the different policy aims that governments pursue via BOT. Similarly, certain economies or industry sectors that are associated with higher risks of financial crime should apply more stringent thresholds. Whilst thresholds can always be exploited by individuals seeking to avoid disclosure requirements by limiting their ownership stakes to just below the level stipulated in law, having low thresholds makes this more difficult. Moreover, where a robust definition of BO exists, which incorporates the substantive (and less common) criteria of ownership and control detailed above, certain individuals may still have to disclose their BO of a company, even if their ownership falls below the threshold level. [21] Based on OO’s experience supporting BO implementations, several countries find that a threshold falling somewhere between 5% and 15% – but sometimes as low as 0% for some people or sectors – is a good balance between the various issues discussed in this section.

Box 3: Thresholds in international policy

No clear international consensus has emerged over the level at which thresholds should be set, although there is evidence of a trend over recent years towards lower thresholds.

In its 2014 guidance on BOT, FATF does not recommend a specific threshold level, but mentions a 25% figure in the context of examples to illustrate how thresholds would work. [22]

Several of the early implementers of public BO registers, including the UK [23] and Ukraine, [24] adopted a 25% threshold in 2015, which was also incorporated into other leading international policy instruments such as the EU’s AMLD4 in the same year. [25]

However, there appears to be increasing recognition internationally that this threshold level leaves many relevant beneficial owners outside of the disclosures. A number of countries have applied lower thresholds in their more recent legislation. This includes, in 2020, the national BO laws for Argentina (1 share or above), [26] Senegal (2%), [27] Nigeria (5%), [28] Paraguay (10%), [29] Kenya (10%), [30] and the Cayman Islands (10%). [31]

Policy goals and a risk-based approach to thresholds

When setting threshold levels, governments should start by examining the policy goals behind their drive to create BO registers. These can include tackling corruption, money laundering, terrorism financing, and tax evasion, or supporting economic activity by lowering the chance of fraud and the cost of due diligence. These policy goals are not mutually exclusive and many countries implement BO registers to pursue several of these aims in tandem. A low threshold is necessary to capture data on the relevant beneficial owners that enable governments to meet the majority of these policy goals.

When setting thresholds, OO recommends that implementers adopt a risk-based approach (RBA) to most effectively meet their specific policy goals. High thresholds leave a disclosure regime vulnerable to loopholes, whilst low thresholds enable authorities to capture more data on those with relationships of ownership or control over corporate vehicles.

Under some circumstances, applying an RBA may lead countries to apply different thresholds across different sectors of the economy. For example, an economy highly dependent on revenues from resource extraction – a sector known to be prone to corruption32 – may apply a lower threshold for their extractive sector disclosures than for the rest of the economy. In such cases, care should be taken to avoid creating a loophole where companies can choose which disclosure regime they fall under. To mitigate this, there should be a clear definition of each economic sector to which a particular threshold applies.

However, implementing low thresholds does involve some challenges. It may increase the reporting burden on companies and is likely to require more state investment to communicate and explain how to comply with the disclosure requirements. Additionally, the lower the threshold is set, the more challenging it is for companies to be up to date with accurate identification of beneficial owners. In complex corporate structures, by the time the information of changes in BO gets to the declaring entity at the bottom of a holding structure, it is possible that there is already a new change going on at the top of the structure. The policy benefits and transparency of very low thresholds – e.g. under 5% – should be considered against the costs of implementation for government and the ability to comply from a business administration perspective for the private sector. Governments will need to judge the trade-off between these costs and outcomes. [33]

The following section outlines how to take a risk-based approach to thresholds to meet two policy objectives: tackling corruption and money laundering, and improving the business environment.

Tackling corruption and money laundering

In order for BOT to reduce corruption and money laundering, thresholds should be determined in light of the corruption risks present in the jurisdiction, and specific risks associated with the sector(s) or types of legal entities that will be subject to disclosure requirements. Contrary to a legal definition of BO, where a single definition leads to more effective disclosure, it is possible to set different thresholds within a single economy, as certain sectors may be deemed to be higher risk and countries can respond to this by implementing a lower threshold. Employing an RBA to BOT can help target limited government resources towards tackling higher risk areas by applying lower thresholds to certain higher risk sectors – such as extractive companies – or classes of individuals – for example, politically exposed persons (PEPs).

Sector-specific thresholds

This is most frequently seen in the case of the extractive industries, which has been identified as posing a significant corruption risk.34 Armenia, for instance, moved from a 20% threshold for BO in its 2008 AML law [35] to a 10% level for its 2019 mining sector disclosures. [36] Similarly, Liberia adopted a 5% threshold for mining, oil, gas, and agriculture, versus a higher 10% threshold for the forestry sector. [37] Ghana has adopted a 0% threshold for all locally registered extractive sector companies declaring to the Registrar under the amended Companies Act of 2019, No 992. Foreign extractive companies operating in Ghana will be subject to a 5% disclosure threshold. [38] Sector-specific thresholds are easier to implement in regulated industries or other situations where authorities know which companies are operating in a given sector, and therefore also which companies are expected to declare at a given threshold. Without this guarantee, there is a risk that ownership or control interests will be hidden in the most permissive disclosure regime, by misdeclaring the sector in which a company is operating.

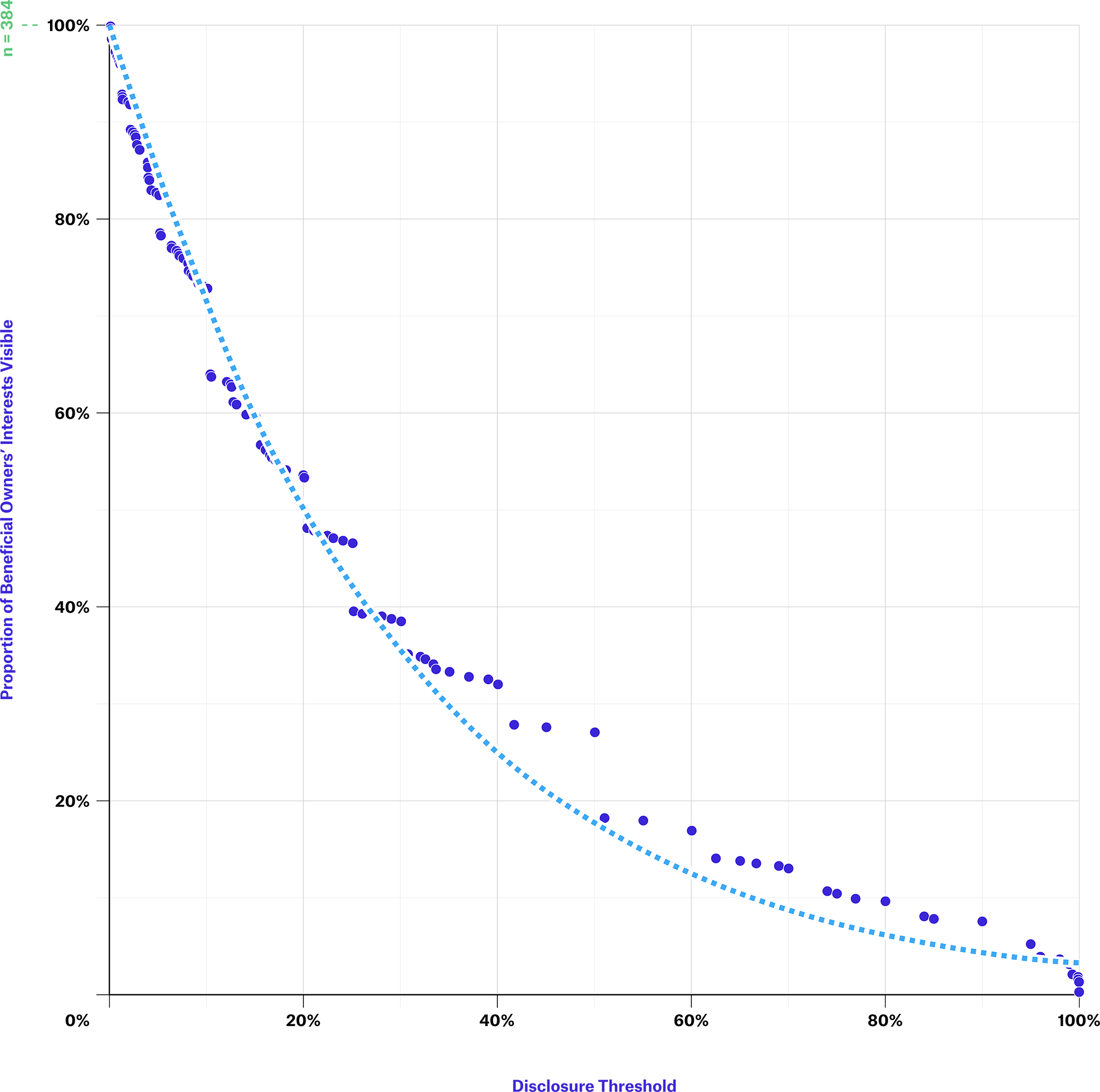

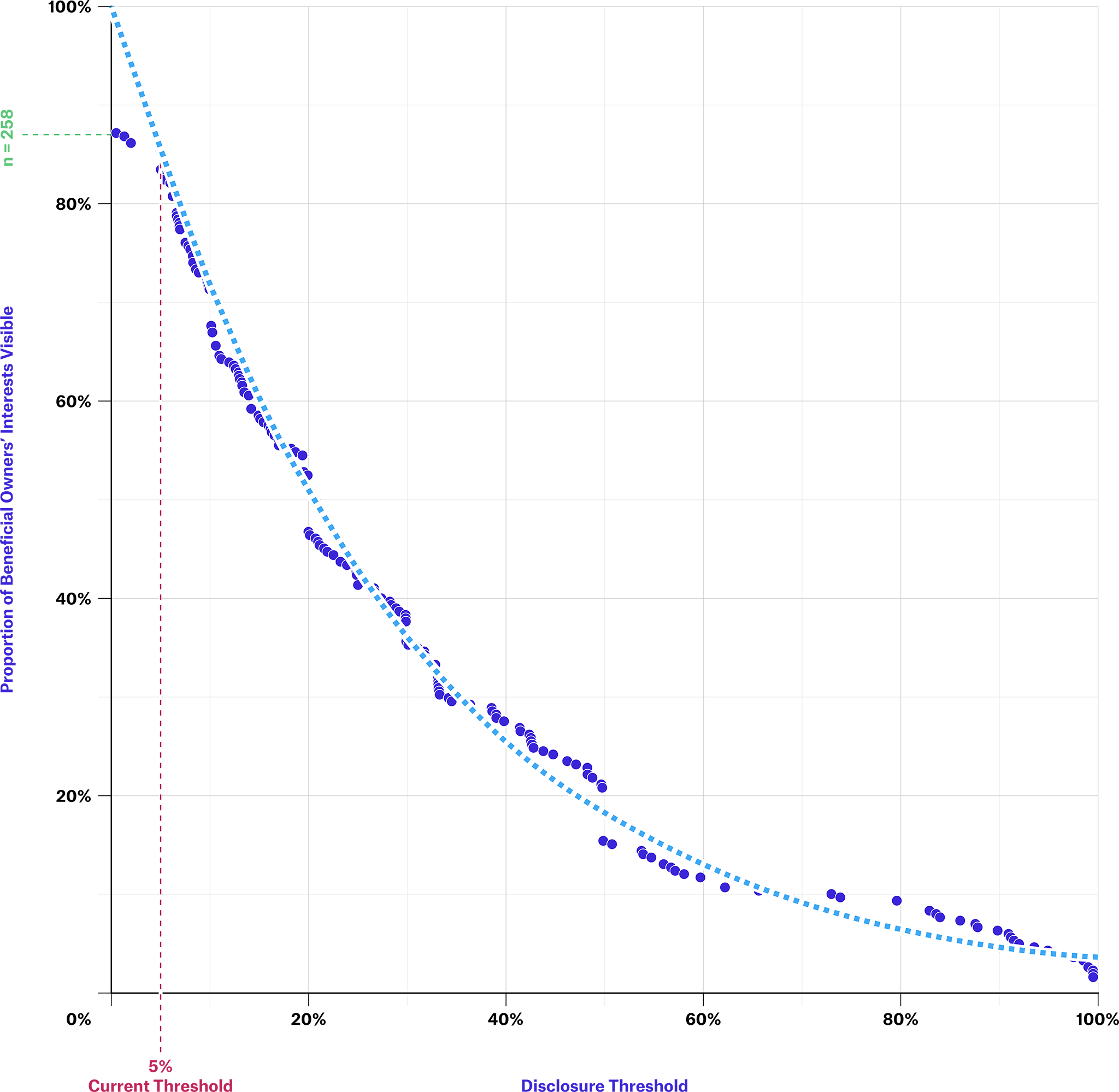

Setting low thresholds ensures that a greater number of beneficial owners are disclosed to authorities. Examination of the data from Nigeria’s extractive industry disclosures in Figure 2 demonstrates the extent to which different thresholds can alter the number of interests disclosed by beneficial owners. If Nigeria had applied a 20% threshold for its extractive industries disclosure requirements, rather than effectively having no threshold level, then the number of reported interests would have halved. This would very likely have had detrimental effects on the policy aims of helping to prevent or investigate corruption cases linked to the sector. By comparison, Myanmar has set a threshold of 5% for its extractives disclosures. Had the threshold been set at 20%, around 40% of the beneficial owners’ interests included in the data would not have been disclosed to authorities (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. Visibility of beneficial ownership in extractive companies in Nigeria at different thresholds (based on disclosures on the NEITI portal)

Graph showing the proportion of beneficial owners visible at different hypothetical threshold levels in Nigeria’s extractives sector. It is based on an experimental treatment of NEITI bulk data, analysing declared percentages ownership and control from the beneficial ownership disclosures of Nigeria’s extractives companies to determine the effect of adjusting the threshold on visibility of BOs. The sample size (n=384) is the total number of beneficial owners’ interests disclosed.

Source: Nigeria Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative (NEITI), “Beneficial Ownership Portal”. Available for bulk download from: https://bo.neiti.gov.ng/company_excel_download/xls (Oil and Gas); and: https://bo.neiti.gov.ng/company_excel_download_sm/xls (Solid Minerals) [Accessed 11 May 2020]

Figure 3. Visibility of beneficial ownership in extractive companies in Myanmar at different thresholds (based on disclosures on the MEITI portal)

Graph showing the proportion of beneficial owners visible at different hypothetical threshold levels in Myanmar’s extractives sector. It is based on an experimental treatment of MEITI bulk data, analysing declared percentages ownership and control from the beneficial ownership disclosures of Myanmar’s extractives companies at a 5% threshold to determine the effect on visibility of BOs of adjusting the threshold. Disclosures beneath 5% are voluntary. The line of best fit has been extrapolated to show what the hypothetical total number of disclosures could be if the threshold were set at 0%. The sample size (n=258) is the total number of beneficial owners’ interests disclosed.

Source: Myanmar Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative (MEITI), “Beneficial Ownership Disclosures”. Available for bulk download from: https://bo.dica.gov.mm/pages/bo-disclosure [Accessed 13 May 2020]

Politically exposed persons [39]

In terms of individuals, for PEPs – those holding senior political office and their close family or associates – an extremely low or 0% BO threshold may be justified. It is widely recognised that the influence and power PEPs derive from their positions can be abused for the purpose of corruption, bribery, and money laundering. [40]

In July 2020 in Kenya, the press reported that a cousin of President Uhuru Kenyatta would likely benefit from Kenyatta’s decision to abolish a tax on gambling as he indirectly held stakes in the sector via shareholdings of between 0.5% and 3% in affiliated companies. [41] A 0% threshold for PEPs can help bring such potential conflicts of interest to light at an early stage. Thresholds for PEPs in Armenia were set at 0% in its 2020 extractive industry disclosures. This is in line with the EITI’s guidance on PEPs, and also followed allegations that stakes in mining firms had been illegally sold to firms controlled by politically-connected figures after the revolution in 2018. [42]

Avoiding thresholds

Authorities and regulated entities should remain mindful that thresholds are only a minimum level for triggering BO disclosure requirements, and that further investigation may be required for entities and individuals deemed suspicious or high risk but which fall below this level. [43] Implementers should consider that high thresholds can serve as an impediment to investigations of individuals and entities that do not meet this threshold. This was illustrated in the Cayman Islands in August 2020 when the Ombudsman’s Office ordered the Registrar of Companies not to collect information on individuals who possessed ownership stakes below the level legally mandated in the territory’s Company Law. This meant that an investigation would have to use BO information held by the company itself (thus tipping it off to the investigation), or make a special access request to the register, which adds time and bureaucracy to the investigation. [44]

A threshold set at any level involves a risk that illicit actors will deliberately circumvent the legislation by limiting their ownership stake to just below the threshold percentage. This was clearly illustrated in the Russian Laundromat case, for example, in which USD 20.8 billion was reportedly transferred from 19 Russian banks into Moldova and then on to other international destinations. The perpetrators reportedly avoided the BO disclosure requirements at 5% by using multiple entities and limiting their shares to 4.9% per entity. When Moldovan authorities reduced the threshold to 1%, those involved altered their strategy to limit their shareholdings to 0.9%. [45] More sophisticated schemes of circumventing thresholds have also been identified, including via use of circular ownership structures. [46] Such schemes again emphasise the importance of only using thresholds as one component of a far broader and more substantive definition of what constitutes BO.

Improving the business environment

In order to manage operational and reputational risks, businesses require good visibility of company ownership and to comply with AML/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CTF) and Know-Your-Customer (KYC) legislation. In the absence of public BO registers, companies often purchase BO data from third party suppliers who are keen users of the BO data that is publicly available. As one of the main providers, Dun & Bradstreet say, “to accurately calculate the aggregated beneficial ownership, a 10% or 25% threshold may not be enough. Determining ownership as low as 1% to calculate the total ownership percentages across various owners may be required for the compliance officers to be confident.” [47]

For businesses to operate with confidence, lower thresholds are preferable, as more data will increase visibility. On the other hand, lower thresholds may increase the cost of due diligence for AML-regulated entities, although the existence of publicly available registers can help offset these costs. In addition, evidence from countries like the UK have already demonstrated that the cost of compliance with BO disclosure regulations is low for the vast majority of businesses. [48]

Footnotes

[21] For example, an individual could still qualify as a beneficial owner if they have a right to enjoyment of substantial company assets, even if they control few or no shares in that entity.

[22] Financial Action Task Force, “Transparency and Beneficial Ownership”. October 2014. Available at: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Guidance-transparency-beneficial-ownership.pdf [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[23] UK Legislation,”Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015”. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/26/pdfs/ukpga_20150026_en.pdf [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[24] Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, “Beneficial ownership in Ukraine: Description and road map”. Available at: https://eiti.org/files/documents/ukraine_bo_roadmap_in_english.pdf [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[25] Official Journal of the European Union, “Directive (EU) 2015/849 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2015”. 5 June 2015. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32015L0849&from=EN [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[26] The Official Gazette of the Argentine Republic, “Federal Administration of Public Revenue”. 15 April 2020. Available at: https://www.boletinoficial.gob.ar/detalleAviso/primera/227833/20200415 [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[27] Interview with EITI Francophone Director, 2 September 2020.

[28] Section 868 of the Companies and Allied Matters Act, 2020 which defines a Person of Significant Control. See: https://www.proshareng.com/admin/upload/report/13880-Companies%20and%20Allied%20Matters%20Act,%202020_-proshare.pdf.

[29] Biblioteca y Archivo del Congreso Nacional, “Law No. 6446 / Creates the Administrative Registry of People and Legal Structures and the Administrative Registry of Final Beneficiaries of Paraguay”. 20 January 2020. Available at: https://www.bacn.gov.py/leyes-paraguayas/9116/ley-n-6446-crea-el-registroadministrativo-de-personas-y-estructuras-juridicas-y-el-registro-administrativo-de-beneficiarios-finales-del-paraguay [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[30] Kenya Subsidiary Legislation,”The Companies Beneficial Ownership Regulations”. 2020 Available at: https://brs.go.ke/assets/downloads/The%20Companies%20(Beneficial%20Ownership%20Information)%20Regulation%202020.pdf [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[31] Cayman Islands Proceeds of Law (2020 Revision), “Anti-Money Laundering Regulations”. 9 January 2020. Available at: https://www.cima.ky/upimages/commonfiles/1580219233Anti-MoneyLaunderingRegulations2020Revision_1580219233.pdf [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[32] The Economist, “Bribery pays – if you don’t get caught”. 27 August 2020. Available at: https://www.economist.com/business/2020/08/27/bribery-pays-if-you-dontget-caught [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[33] This is not to say this is never feasible. Some countries, such as Curaçao, have set the threshold at a single share. See: Tax Justice Network, “Argentina finally has a beneficial ownership register”. 20 April 2020. Available at: https://www.taxjustice.net/2020/04/20/argentina-finally-has-a-beneficial-ownership-register-now-itshould-make-it-public/ [Accessed 29 August 2020].

[34] The Economist, “Bribery pays – if you don’t get caught”. 27 August 2020. Available at: https://www.economist.com/business/2020/08/27/bribery-pays-if-you-dontget-caught [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[35] Republic of Armenia Law, “On Combating Money Laundering and Terrorism Financing”. 21 June 2008. Available at: https://www.cba.am/Storage/EN/FDK/Regulation_old/law_on_combating_money_laundering_and_terrorism_financing_eng.pdf [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[36] As of July 2020, this applies only to the extractive industries, though an expansion of the disclosure regime to cover all sectors is planned for late 2020. See: https://www.arlis.am/DocumentView.aspx?DocID=131518.

[37] Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, “Beneficial Ownership Roadmap”. December 2016. Available at: https://eiti.org/files/documents/leiti_bo_roadmap.pdf [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[38] Ghana Business News, “Ghana to deploy Beneficial Ownership Register in October”. 9 September 2020. Available at: https://www.ghanabusinessnews.com/2020/09/09/ghana-to-deploy-beneficial-ownership-register-in-october/ [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[39] International definitions of PEPs commonly include not just individuals that directly hold political office, but also those close to them, such as their spouse and immediate family. See, for example, United Nations, “Convention Against Corruption”, Article 52(1). Available at: https://www.unodc.org/documents/brussels/UN_Convention_Against_Corruption.pdf [Accessed 6 September 2020].

[40] Financial Action Task Force Guidance, “Politically Exposed Persons (Recommendations 12 and 22)”. June 2013. Available at: https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/recommendations/Guidance-PEP-Rec12-22.pdf [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[41] The Elephant, “It’s Our Turn to Eat: Cousin of Kenya’s President Has Stake in Sportpesa Betting Firm”. 2 July 2020. Available at: https://www.theelephant.info/features/2020/07/02/its-our-turn-to-eat-cousin-of-kenyas-president-has-stake-in-sportpesa-betting-firm/ [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[42] For more on these allegations, see, for example: https://arminfo.info/full_news.php?id=51522&lang=3.

[43] World Bank, “The Puppet Masters: How the Corrupt Use Legal Structures to Hide Stolen Assets and What to Do About It”. 2011. Available at: https://star.worldbank.org/sites/star/files/puppetmastersv1.pdf [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[44] Cayman Compass, “Ombudsman orders registrar to stop collecting personal information”. 14 August 2020. Available at: https://www.caymancompass.com/2020/08/14/ombudsman-orders-registrar-to-stop-collecting-personal-information/ [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[45] Committee of Inquiry into Money Laundering, Tax Avoidance and Tax Evasion, “Public Hearing Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs): ‘Ins and Outs’ and the Russian ‘Laundromat’ Case”. 21 June 2017. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/128621/PANA%2021%20June%20pm_Verbatim%20Report_EN.pdf [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[46] The Tax Justice Network has written in detail about how circular ownership structures can be used to avoid disclosure thresholds. See: Tax Justice Network, “More beneficial ownership loopholes to plug”. 6 September 2019. Available at: https://www.taxjustice.net/2019/09/06/more-beneficial-ownership-loopholes-to-plugcircular-ownership-control-with-little-ownership-and-companies-as-parties-to-the-trust/ [Accessed 2 August 2020].

[47] Dun & Bradstreet, “How Compliance Practices Should Adapt to Increased Beneficial Ownership Scrutiny”. 2016. Available at: https://www.dnb.co.uk/content/dam/english/dnb-solutions/supply-management/beneficial-ownership-white-paper.pdf [Accessed 29 September 2020].

[48] For instance, in a review of the UK register, the median cost of compliance in the UK was £287. See: Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, “Review of the implementation of the PSC Register”. March 2019. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/822823/review-implementation-psc-register.pdf [Accessed 1 August 2020].